I'm calling this the "I Don't Understand Accident" because I don't understand how these pilots made so many poor decisions on their way to destroying an airplane and almost killing everyone on board.

— James Albright

Updated:

2020-11-28

You could argue they are very lucky. I must admit they are doing a type of flying I don't often do. But still, I don't understand.

1

Accident report

- Date: 15 August 2019

- Time: 1540

- Type: Cessna 680A Citation Latitude

- Operator: JRM Air LLC

- Registration: N8JR

- Fatalities: 0 of 2 crew, 0 of 3 passengers

- Aircraft Fate: Destroyed

- Phase: Landing

- Airport: (Departure) Statesville Municipal Airport, NC (KSVH), USA

- Airport: (Destination) Elizabethton Municipal Airport, TN (0A9), USA

2

Narrative

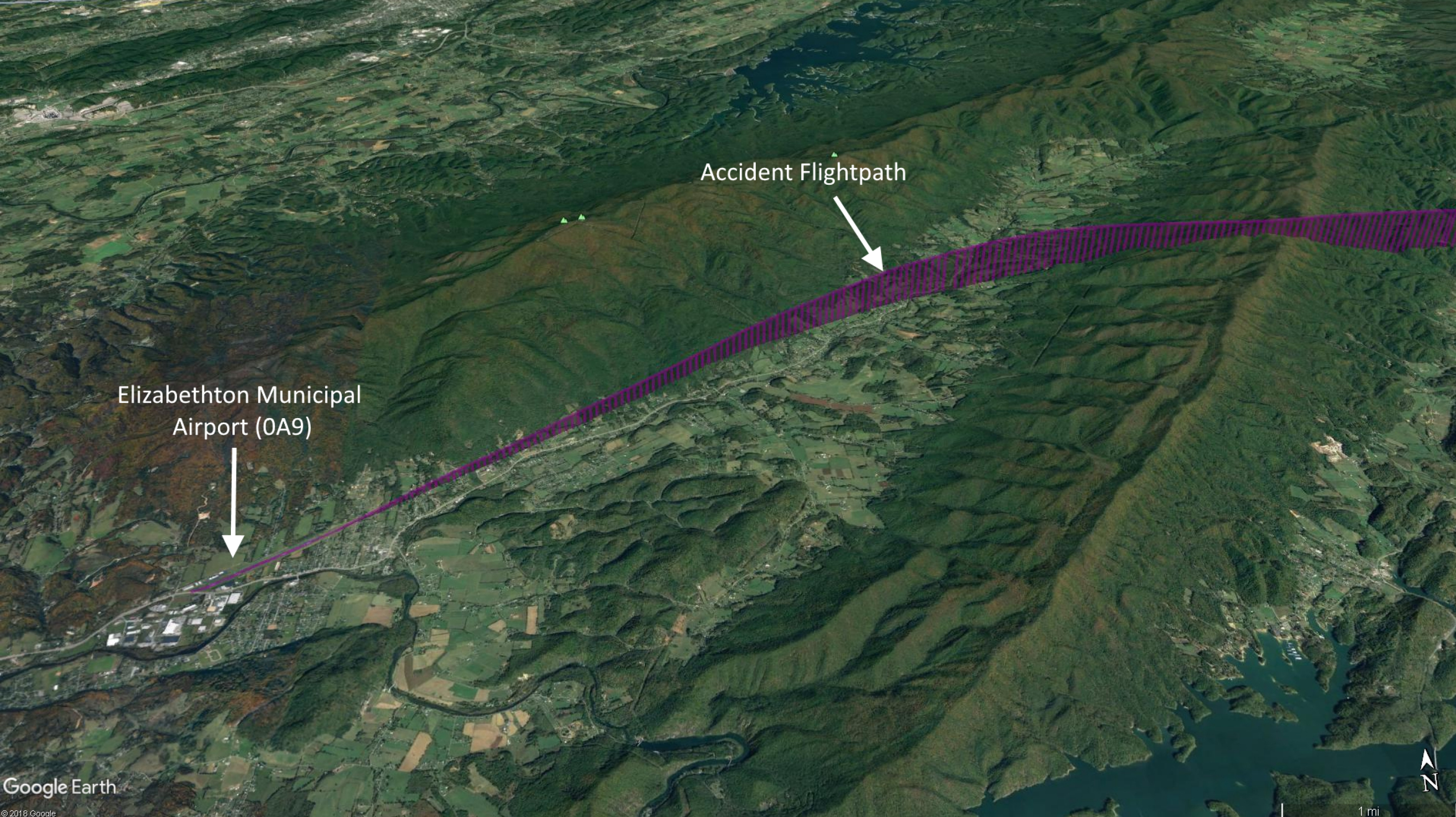

- On August 15, 2019, about 1537 eastern daylight time, a Textron Aviation Inc. 680A, N8JR, was destroyed when it was involved in an accident near Elizabethton, Tennessee. The pilot and copilot were not injured and the three passengers sustained minor injuries. The airplane was operated as a Title 14 Code of Federal Regulations Part 91 business flight.

- The flight departed Statesville Regional Airport (SVH), Statesville, North Carolina, at 1519 and climbed to 12,500 ft mean sea level (msl). The preflight, departure, and en route portions of the flight were routine. Unless otherwise noted, the following sequence of events was derived from the download and review of data from onboard data and voice recording systems, and all speeds are indicated airspeed.

- At 1527 (about 8 minutes after takeoff), the airplane began a descent from 12,500 ft msl to 5,400 ft msl; during the descent, the airplane turned right to varying headings between 325º and 342º. During this time, the flight crew discussed clouds in the area and the best ways to maneuver around them as well as traffic in the area and landmarks, including ridge lines, to help them identify 0A9. About 1530, the copilot announced via the airport's common traffic advisory frequency their intention to land on runway 24. At 1532:11, the pilot stated, "well it wouldn't hurt to slow down." About 33 seconds later, the descent resumed, and the airspeed decreased to 200 knots with the autothrottle engaged.

Source: ERA19FA248, Factual Information

The NTSB did not make a big deal about this, but note they were looking at ridge lines on their approach to Runway 24.

- At 1533:00, the airplane began to turn left, and the crew conversation indicated that they had some difficulty visually acquiring the airport; the airplane then turned right and began to climb. At 1535:02, the descent resumed, and 10 seconds later the terrain avoidance and warning system (TAWS) excessive closure rate caution and warning alerts sounded in the cockpit as the airplane crossed a ridge at 710 ft above ground level (agl). The copilot asked the pilot if he saw the terrain, and the pilot responded, "yeah, I got it."

- At 1535:27, the airplane began a shallow left turn to an extended final. As the approach to landing resumed, the descent rate increased; the autothrottle positioned the throttles to their minimum, 6º throttle lever angle, and the airspeed increased to 220 knots. At 1536:12, the pilot asked the copilot to position the flaps to the flaps 1 setting. The crew then manually positioned the throttles to 0º throttle lever angle, which disengaged the autothrottle; the throttles were not moved for the remainder of the approach. At 1536:29, the pilot stated, "slow down." At 1536:31, the pilot asked the copilot to lower the landing gear, and the copilot responded that he would after the airplane slowed down more. At 1536:36, the speedbrake lever was partially extended to a 33º lever angle, and the TAWS excessive descent rate caution alert sounded about 5 seconds later.

- At 1536:47, about 3 nautical miles from touchdown and at 2,783 ft msl (781 ft agl), the speedbrake lever was extended to 41º for a total of 21 seconds then retracted after the airspeed decreased to 205 knots. At 1536:50, the landing gear were extended, and 7 seconds later, flaps 2 (15°) was selected; these actions were performed when the airplane reached the maximum speeds to perform those functions (205 knots and 195 knots, respectively).

- As the flaps were extending, the TAWS forward looking terrain alert rate of terrain closure caution alert sounded twice (at 1536:59 and at 1537:09), then a warning alert sounded (at 1537:11). The airplane was at an altitude of 2,159 ft msl (471 ft agl). Following these alerts, the copilot selected full flaps and the descent rate and airspeed decreased.

- At 1537:26, the copilot stated, "and I don't need to tell ya, we're really fast," and the pilot responded, "I'm at idle." Six seconds later, the pilot asked, "do I need to go around?" and the copilot responded, "no." At 1537:31, about 270 ft agl, the speedbrakes were partially extended for 5 seconds (to 140 ft agl). The pilot then stated, "I got the speed brakes out," to which the copilot responded, "well you should get rid of those because we don't wanna get a CAS [Crew Alerting System] m- or a thing sent to ya." Eight seconds before touchdown, at 1537:41, the pilot stated, "alright, I'll be on the T-Rs [thrust reversers] quickly." For the computed airplane weight, the reference speed (Vref) for the final approach was 108 knots; the airplane's airspeed at the runway's displaced threshold was 126 knots. Five seconds before touchdown, the airplane's descent rate was over 1,500 ft per minute (fpm).

- According to airport surveillance video and recorded data, the airplane first briefly touched down with a bounce on the runway designator about 240 ft past the displaced threshold with about 3,860 ft of paved surface remaining. The airplane then touched down two more times, bouncing each time, then continued airborne over the runway until it touched down a fourth time with about 1,120 ft of paved surface remaining.

- When the airplane touched down initially at 1537:49, it was traveling 126 knots (18 knots above Vref) and had a descent rate of 600 fpm (the maximum allowed per the airplane flight manual [AFM]). All three landing gear registered "on-ground" simultaneously with a vertical acceleration of 1.4 gravitational acceleration (g), and thrust reverser deployment was commanded 0.4 second after the landing gear first touched the ground as the throttles were moved to the reverse idle position; however, the airplane bounced after touching down for 0.6 second and was airborne again before the thrust reverser command could be executed.

- When the airplane touched down a second time, 1.2 seconds later at 1.6 g, the nose landing gear touched down first, followed immediately by the right main landing gear. The left main landing gear never registered on-ground during the touchdown, and the airplane bounced and became airborne again after 0.4 second.

- The airplane touched down a third time, 1.8 seconds later at 1.7 g and about 1,000 ft down the runway with about 3,100 ft of paved surface remaining. The thrust reversers unlocked 0.4 second after all three landing gear registered on-ground because the reverser deployment command from the first touchdown was still active. Almost immediately after the thrust reversers unlocked, the pilot advanced the throttles to idle, sending a thrust reverser stow command at 1537:54; however, the landing gear status changed to "in-air" almost simultaneously when the command was executed.

- The airplane bounced after 0.6 second and became airborne a third time, and the in-air landing gear status triggered a cut in hydraulic power to the thrust reverser actuators, which is intended to prevent the airborne deployment of a thrust reverser. The cut in hydraulic power to the thrust reversers allowed the unlocked thrust reversers to be pulled open by aerodynamic forces. The amber "T/R UNLOCK CAS" message illuminated and the thrust reverser emergency stow switches began to flash. The pilot advanced the throttles to maximum takeoff power 0.7 second later in an attempt to go around; however, the thrust reversers reached full deployment 0.4 second after that. The airplane's full authority digital engine controls (FADEC), by design, prevented an increase in engine power while the thrust reversers were deployed. The red "T/R DEPLOY CAS" message was displayed in the cockpit, indicating that the thrust reversers were deployed, and the thrust reverser emergency stow switches continued to flash.

- The pilots later reported that they attempted to conduct a go-around; however, the engines did not respond as expected, so they landed straight ahead on the runway. While the airplane was airborne, the crew partially retracted the flaps as the airspeed decreased from 119 knots to 91 knots. The pilot retarded the throttles partially but not to idle, then pushed the throttles forward again with no effect because the FADEC continued to prevent an increase in thrust; the pilot then pulled back the throttles to idle. While airborne for 9.6 seconds, the airplane reached an altitude of about 24 ft agl.

- The stick shaker activated 0.5 second before the airplane touched down for the fourth and final time at 1538:03, warning of an imminent stall. The airplane touched down hard with a peak acceleration of 3.2 g on the left and right main landing gear, then the left main landing gear came off the ground then contacted the ground again. The nose gear contacted the ground about 0.5 second later. The left inboard wheel brake pressure increased to near maximum after the left main gear touched down; however, the left outboard and right wheel brake pressure did not increase significantly, indicating that only the left inboard tire was firmly contacting the runway. When all three landing gear touched down on the runway at 1538:06, the thrust reverser system was reenergized and the thrust reversers stowed 0.9 second later because the throttles were at idle.

- Airport surveillance video showed that the right main landing gear collapsed at 1538:04 and that the outboard section of the right wing contacted the runway immediately thereafter. The airplane then departed the 97-ft-long paved surface beyond the end of the runway and traveled through a 400-ft-long open area of grass, down an embankment, through a creek, through a chain-link fence, and up an embankment. Photographs of the accident scene showed that the airplane came to rest on the edge of a four-lane highway about 600 ft beyond the runway threshold. In postaccident interviews with the flight crew, they reported that they secured the engines after the airplane came to a stop and assisted the passengers with the evacuation through the main entry door as a postaccident fire erupted, which eventually destroyed the airplane.

Source: ERA19FA248, Factual Information

The main entrance door swings downward but is blocked when the aircraft gear collapses, as is typical with many business jets. The primary passenger was Dale Earnhardt, Jr., a professional race car driver. I suspect his calm under pressure enabled him to keep his wits about him, and attempt to open the door (it took several tries) partially, exit, reach back for a child, and then run away followed by his wife. Video: Earnhardt family seen escaping plane crash.

3

Analysis

I think this accident pretty much analyzes itself, but lets add a few things to what the NTSB covered.

They [both pilots] reported that they have been to 0A9 “several times.” The flight crew reported they did not utilize air traffic services during the flight.

Source: NTSB Record of Conversation, p. 1

The wind was calm during the landing.

Source: NTSB Record of Conversation, p. 3

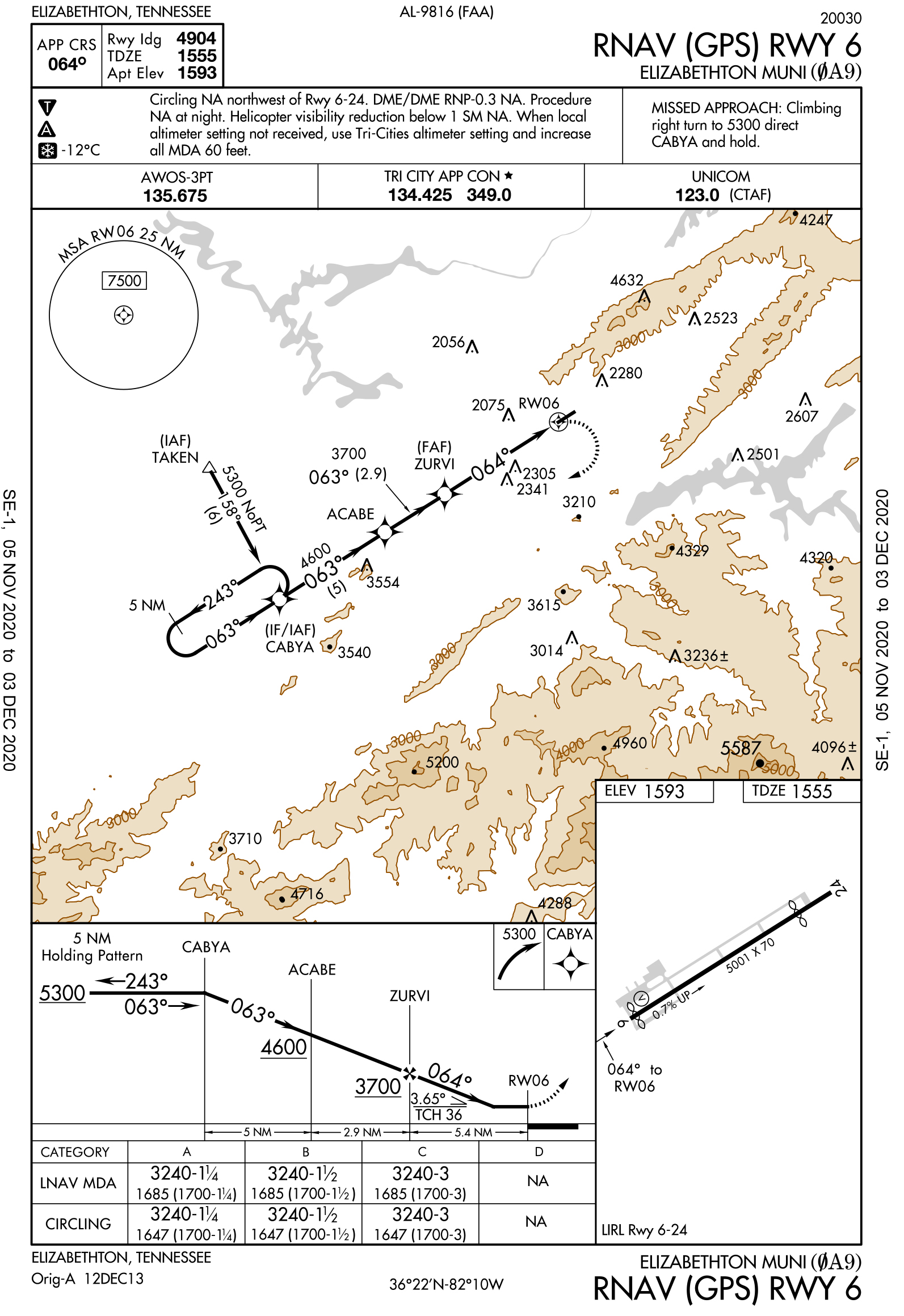

Reading the transcript of the cockpit voice recorder it appears it took the pilots a while to find the airport as they were simultaneously trying to avoid the weather and the terrain. The winds were calm and they were approaching the runway with the higher terrain and without an instrument approach. Under those circumstances, I do not understand why they didn't head for Runway 06 instead, where the terrain wasn't as challenging and they would have had help in locating the runway.

When faced with terrain and the need to get down, most pilots understand that slowing down will be a challenge. Both pilots voiced concern over the excess speed several times during the approach.

At 1537:26, the copilot stated, "and I don't need to tell ya, we're really fast," and the pilot responded, "I'm at idle."

Source: NTSB Record of Conversation, ERA19FA248

If it seems like the pilot was asking the copilot for permission to go around, I think he was:

Six seconds later, the pilot asked, "do I need to go around?" and the copilot responded, "no."

Source: NTSB Record of Conversation, ERA19FA248

According to the copilot, who also served as the director of operations for the airplane operator, he and the pilot were the only pilots who flew the accident airplane. Both the pilot and copilot were qualified to act as pilot-in-command. The normal procedure for the crew was to "switch seats" often, with the pilot in the left seat always acting as pilot-in-command. As the director of operations, the copilot on the accident flight was also the direct supervisor of the pilot in the left seat. The pilot reported that this relationship neither influenced his decisions as pilot-in-command nor diminished his command authority. When asked if he thought there may have been repercussions from the copilot if he had discontinued the approach, the pilot responded "absolutely not."

Source: ERA19FA248, p. 9

The pilot may have believed that statement when he made it, but I think on a subconscious level he was deferring the decision to go around to his boss.

When the copilot was asked in postaccident interviews if he thought the approach was stabilized, he responded "no."

Source: ERA19FA248, p. 10

Many of us preach the need for stabilized approaches but I think most of us are well practiced at salvaging unstable approaches to no ill effect. This only reinforces in us that we don't really need to go around when things get unstable. What I don't understand in this situation is how the pilots were able to ignore the cascading effect of one problem after another. There has to come a time when you as a pilot recognize you are not in a normal situation, cannot make it normal in the near future, and that the best course of action is a "do over." We owe it to ourselves to learn to appreciate the value of a good "do over."

4

Cause

The National Transportation Safety Board determines the probable cause(s) of this accident to be: The pilot's continuation of an unstabilized approach despite recognizing associated cues and the flight crew's decision not to initiate a go-around before touchdown, which resulted in a bounced landing, a loss of airplane control, a landing gear collapse, and a runway excursion. Contributing to the accident was the pilot's failure to deploy the speedbrakes during the initial touchdown, which may have prevented the runway excursion, and the pilot's attempt to go around after deployment of the thrust reversers.

Source: ERA19FA248, pp. 2-3

References

(Source material)

NTSB Aviation Accident Final Report, Textron Aviation Inc 680A, August 15, 2019, ERA 19FA248