This story has nothing to do with flying airplanes and just a little to do with the military. If you are a pilot carrying a fire arm you might be concerned about my attitude towards fire arms. I am all for the right to carry, but I choose not to carry on an airplane. If I could have prevented all those secret service agents from carrying I would have. But, as should be obvious, I didn't have a vote.

— James Albright

Updated:

2013-09-24

I can't blame you if you want to pass on this story. Some of these are here because they amuse me.

"You are a marksman"

1976

Boot camp in Lackland, Texas wasn't the big ordeal everyone said it would be. Now the fact I was going through as an Air Force officer candidate may have softened things up for me, but it was still boot camp. There were only two possible results, either I passed or I failed. We would leave boot camp and head for our junior year in Air Force ROTC and become cadet officers on our way to becoming real officers. Nothing I did at boot camp would follow me as an officer, except our day on the marksmanship range. If I managed to hit the rings of the target ninety times out of one hundred I would qualify for combat duty, ninety-five times out of one-hundred, I would become an Air Force marksman and get a ribbon. Not just any ribbon, this ribbon would follow me onto active duty. It was my only chance to have a ribbon on my chest when I received my commission. I wanted that ribbon.

It was to be one hundred rounds with an Air Force drill sergeant in charge. We got two hours of instruction operating our M-16 rifles, an hour of range safety, and then an hour on the range. For someone who had never held a pea shooter, much less an automatic rifle, the M-16 was an impressive weapon. I feared it.

The first ninety rounds were carefully scripted. Ten rounds from the standing position. Ten rounds while prone. Ten rounds behind a barricade. Ten rounds timed. They told us how they wanted the first ninety rounds. I am absolutely certain those first ninety rounds were in the bull's eye.

The final ten rounds were from however we wanted: prone, standing, kneeling, behind a barricade, it didn't matter. But they had to be from our weak eye. I am absolutely certain I didn't even hit the target.

Well, you can only do so much. "All safe, all safe on the firing range." With our weapons saftied, we approached our targets and started the count. "Ninety-seven," I counted, "ninety-eight, ninety-nine, one-hundred. That can't be right." I counted again. ". . . one-hundred." I counted again.

The drill sergeant tapped me on the shoulder, "we got a problem, Kay-det?"

"Sergeant," I said, "I counted one-hundred."

"Congratulations," he said, "that makes you a marksman."

"But sergeant," I said, "I am certain I didn't hit the target one hundred times."

"I said you are a marksman, cadet," he said in the gruff voice issued to drill sergeants, "what part of that don't you understand?"

"I am a marksman, sergeant."

"That's what I thought you said." The sergeant marched off.

Another cadet tapped me on the shoulder, "what's the problem?"

I explained my situation and he smiled in recognition.

"You were two guys to my right," he explained, "you didn't see me because you are right handed and had your back to me." I nodded. "I'm right handed too, so I saw you and I saw the cadet between us. She was left handed."

The cadet explained that every time the middle cadet squeezed her trigger, she closed her eyes. "Scared the hell out of me," he said, "but at least she made sure the rifle was pointed down range before she shot."

"So she hit my target ten times," I said, finally recognizing the source of my perfect score. "I need to report this."

"Don't bother," he said, "I already told them my score was bogus and was told to forget about it."

"How'd you do," I asked.

"One-ten out of one-hundred," he said.

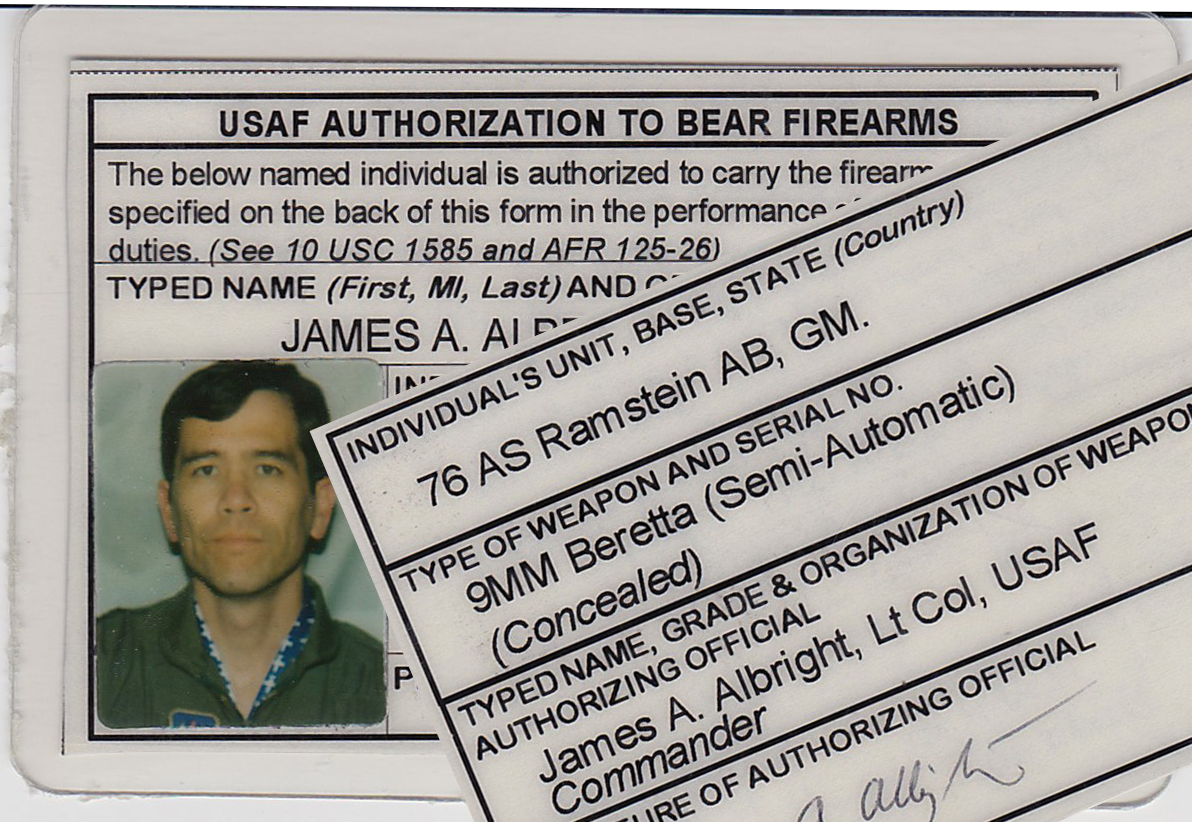

I got my ribbon. I had to requalify twice while on active duty, first with a 38-caliber pistol and then with a 9-milimeter Beretta. As an aircrew commander I was allowed to delegate the duties with the weapon if I thought it wise. I always thought it wise. Except once. . . .

1993

We were deep inside of Russia, back in the days we were still enemies and our airplane enjoyed diplomatic immunity. The 89th required that we travel with at least one crewmember armed, and I always delegated that duty to the flight engineer. I didn't want the hassle of checking the weapon out from the armory, carrying it around, and then having to return it to the armory. My only rule to the engineer: the gun had to be secured in the aircraft safe.

It was one of those typical trips during the cold war. Having a United States airplane on Russian territory was unusual and we were always greeted by the Russian military. After we parked, the airplane was surrounded by twenty KGB, each with a Kalishnikov rifle. I know the Kalishnikov is no match for an M-16, but when there are 20 of them surrounding your airplane and all you've got is a Beretta, you have to admit you are outgunned.

Not that it mattered; we were invited guests of the Russian government. Once our senatorial passengers were off the aircraft, all I had to do was get the airplane fueled, the bills paid, and we could spend the night drinking Vodka, eating potatoes or whatever else it was they ate in this God-forsaken place.

I was in the cockpit, watching the fuel numbers start to increase as the flight engineer supervised from the ground with the Russian fuel truck drivers. I saw the lady Russian officer with the obligatory clipboard and money satchel. I got out of the seat and invited her onto the aircraft. I gestured for her to sit in the cabin and I closed the cabin door behind us. She presented me with the bill, just over three thousand dollars, and I gave her the required cash in U.S. twenties.

As she counted the money, I noticed some commotion outside our windows. It was the flight engineer arguing with the fuel truck driver as the KGB guards looked on. As she counted I noticed the flight engineer disappearing from view, somebody stomping up the air stairs and moving the false wall that hid the safe. There was the sound of somebody trying, and failing, to open the safe. I politely excused myself from my Russian guest, and walked forward, closing the cabin door behind me.

The flight engineer, Senior Master Sergeant Terry Smith, had just opened the safe and his right hand was on the Beretta. "What are you going to do with that weapon, sergeant?"

"I'm gonna kill that commie bastard," he said, "let go of my hand, sir."

"After you kill him," I said, "do you expect me to scrape your remains of the tarmac?"

"I don't care," he said pulling the gun out and overwhelming my grip, "I'm gonna kill that commie bastard."

"Sergeant Smith," I said in my most military tone, "stand at attention." He did so. "Hand the weapon over." He did so, still at attention. "Why are you going to shoot that commie bastard?"

"Because he's cheating us on the fuel."

"How do you know that?"

"Because he says we have to pay a thousand rubles a gallon, major!"

"He's not cheating us," I said.

"He is!"

"Listen to me," I said, "I will make sure that after the exchange from rubles to dollars and liters to gallons that if he did cheat us, I'll shoot the commie bastard. You are going to have to trust me."

Of course they weren't cheating us and our price for jet fuel was the best we had paid that trip. I was more worried about the rust on the outside of the truck seeping into the gas than I was about the price. We made it off the ground and out of Russia and I turned my worries to what to do about Senior Master Sergeant Smith.

As a major, I was what the U.S. military considers an O-4, four steps along officership. Senior Master Sergeant Smith was an E-8, eight steps along the career track as an enlisted non-commissioned officer. He was twice my age, had twice my experience in the Air Force and now I could end all that. We had a week before we got back to the United States and I had a week to consider my options. In the end, I decided a stern talking to was all that was necessary.

After we returned to Andrews I put Senior Master Sergeant Smith into a "military brace" — he was at attention and I was the guy breathing down fire and brimstone — this was something I had seen only done twice before, and I was on the receiving end. I made it clear that if I so deemed it necessary, he would find himself at Leavenworth pounding big rocks into little rocks and his glorious military career would be at an end. I lectured at length that he needed to be more careful when representing the United States of America and just because he had a license to carry a lethal weapon didn't mean he could use that weapon without due cause. "Do I make my self clear, Sergeant"?

"Major," he barked out, still at attention, "yes major, sir!"

I could see he was trembling. He was a fine flight engineer with nearly thirty years in service to his country. I was thirty-six years old with fourteen years in uniform. I had no idea what I was doing. "Sergeant," I said, "return your weapon to the armory. Dismissed."

He saluted, waited for me to return the salute, did an about face and departed my sight forever. I never reported the incident to another soul and wish the story came to an end that day on the Andrews tarmac. It did not.

Six months later I was the 89th Airlift Wing's chief of safety in charge of an office of ten safety inspectors. I got a call aft of midnight from my weapon safety officer. "Major," he said, "we have an unauthorized discharge of a weapon at the armory."

"Anybody hurt," I asked.

"No sir," he answered, "we got lucky."

"Get down there," I said, "collect your evidence. Call law enforcement. Brief me in the morning."

The next morning I found out it was Senior Master Sergeant Smith. He was returning from a trip and returning his weapon. Protocol requires the person returning the weapon place all ammunition on the counter at the armory and take the weapon, in full view of the armory clerk, point the weapon into a fifty gallon drum of sand, and pull the trigger twice. By clearing the weapon in front of the clerk, there can be no doubt the weapon isn't armed. Senior Master Sergeant strolled into the armory about 1 am and slapped his gun and ammo clip onto the counter in front of the airman first class. Back to our rank structure explanation: an airman first class is an E-3; Smith was an E-8.

"Sergeant," the airman said, "you need to clear your weapon."

"The weapon is clear," Smith said, "take it."

"No sergeant," the airman said again, "you need to clear your weapon. Sergeant, please. . ."

Senior Master Sergeant took the pistol and, without aiming, squeezed the trigger twice. One round discharged and shot through the ceiling into the second floor and through a desk chair. It was 1 am and there was nobody there, nobody was hurt.

Senior Master Sergeant was forced to retire and I hear he has a profitable lawn mower dealership in Dixon, Missouri. To this day I believe had that errant bullet killed somebody, I would be guilty of murder. It haunts me still.

As a squadron commander I had to requalify with the Beretta and did so without a second thought. After leaving the firing range I never again touched a fire arm. If we needed a weapon on board, I always delegated the duty to the other pilot or the flight engineer.