The good folks at the F of AA say that whenever you declare an emergency you should make a written record of it. For me, the first time was in 1979 and I made a written record of it. In my own style, of course.

— James Albright

My last check ride in pilot training . . .

14 Sep 1979

The long year of Air Force Undergraduate Pilot Training — UPT, the most important three letters of my twenty-two year existence thus far — was all but over. I had passed every major check ride, I had passed the all important “Fighter Attack Reconnaissance” qualification — what made you a man at Williams Air Force Base, and all I had left was this cross country evaluation. It would be easy.

First Lieutenant Skip Wortham, a more WASP-ish name could not exist, left instructions in my student grade folder. “Plan XC CHD-NTD-RTB 14 NOV 0700.” I was to plan my cross country check ride from Williams, CHD, to Point Mugu Naval Air Station, NTD, and “Return to Base” leaving at 0700. Point Mugu is near Ventura, California. I had never been there, but it would be easy enough.

“Duck soup,” I said to myself as I finished the fuel log and flight plan. Of course I never cooked duck soup, in fact I probably never had duck soup. But in Hawaii if something was easy it was duck soup. This was duck soup. I left the mission paperwork and my grade folder on Lieutenant Wortham’s desk. It was nearly bare, with only a family photo on one side of the desk and his uniform hat on the other. His hat looked just like mine, but where I had a single gold bar his was silver, and where the braid on mine was chewed up from the zipper in my flight suit pocket, his was good as new. Skip, it would seem, is one of those clean as a whistle guys.

I showed up one hour prior to scheduled takeoff, as was expected, and Lieutenant Wortham greeted me coldly and assured me that the check ride should be easy for me, given my record and the quality of my flight planning. “Just don’t have any mental flatus and you will do fine.”

I must have had that confused butter bar look.

“Brain fart,” he said, “Don’t have a brain fart.” He went on to confide that almost half the students he gave these cross country evaluations actually passed, so I had nothing to worry about.

By this point in my ten month flying career, the T-38 was the closest thing I had ever experienced to a pure man-machine marriage. I knew every bolt and bending the airplane to my will was now a matter of thought, no longer of brain-to-hands interface. I would never again have the experience of flying an airplane several times a day for months on end, never again have that blissful union of neurons to jet fuel. But on that day in 1979, I willed myself and the guy in the back seat from Phoenix, Arizona to Ventura, California at nearly six hundred miles an hour, and so it was.

Lieutenant Wortham and I sat at the base operations snack bar at Point Mugu, eating greasy chili dogs and sipping cokes. The Navy line guys were refueling our T-38, parked next to two Navy jets, both ugly monstrosities made more so by their proximity to our sleek, white, rocket.

“What’s the lowest weather minimum authorized for a precision approach?” he asked. “What about the ceiling?” he followed. “What if you don’t have that?” And so it went. The oral evaluation was where most of the check ride busts happened at this stage of the game. But after ten months this was where a lot of pilot candidates started to forget the early data because we were having too much fun. Somehow it still stuck with me. It was duck soup.

As the questions continued he became more and more relaxed. I think that as it became apparent I would be one of those almost half who actually passed, he started to lower the evaluator-to-evaluatee barrier. Lieutenant Wortham became Skip. How can any adult go by Skip? He was still Lieutenant Wortham to me.

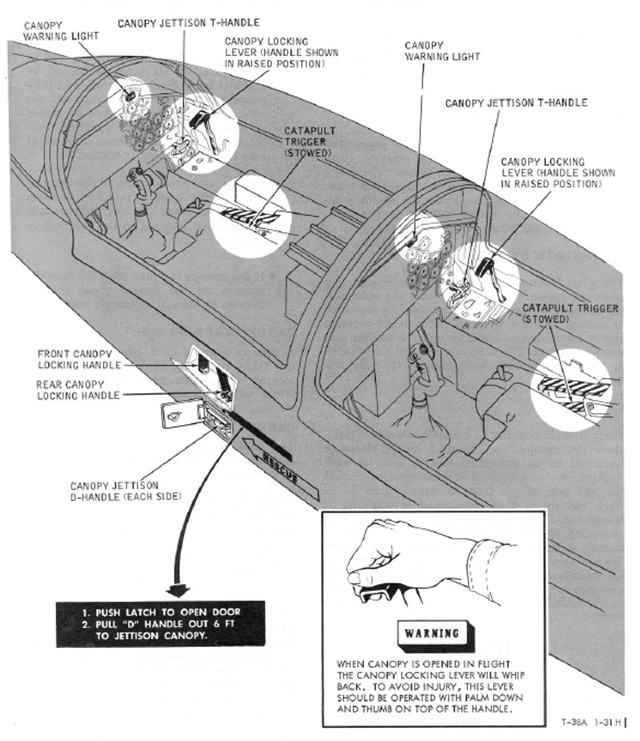

The aircraft was finally fueled and I did my quick exterior preflight inspection and hopped into the front seat. As Wortham plugged his helmet into the aircraft interphone system I could hear he was humming to himself. I clenched my right fist above my head and moved it toward my open left palm. The navy linesman nodded and connected the external air cart to the aircraft. A few button presses later and both engines were cooking with gas. I held both hands above me, resting on the metal bar lining the front of the canopy windshield. From the two mirrors I could see Skip was doing the same in the back seat. With this precaution taken, the linesman scurried underneath the aircraft to disconnect the external air cart and remove the wheel chocks.

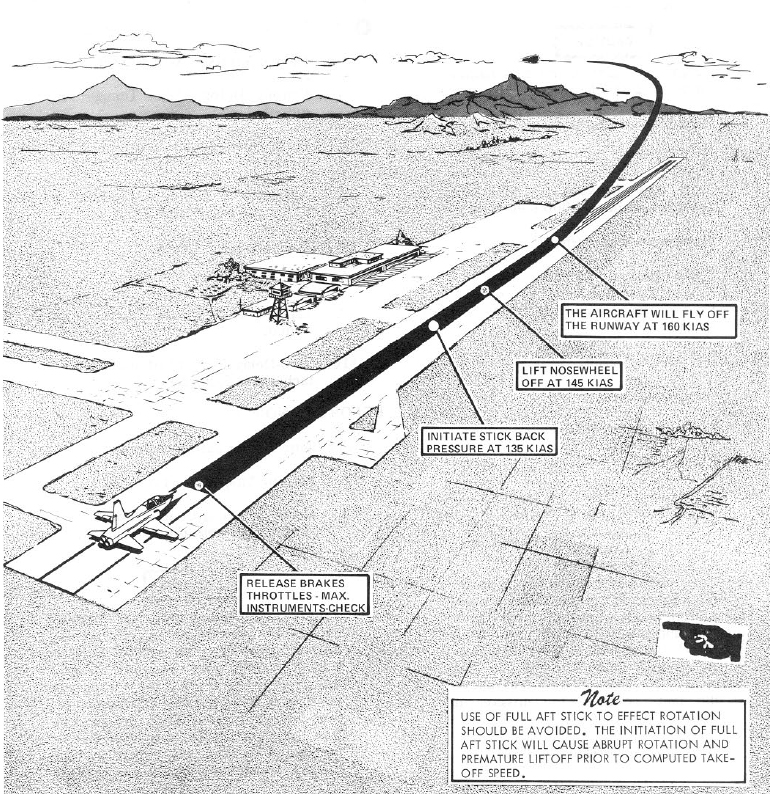

After a short taxi, Mugu Tower cleared us for takeoff and we both lowered our canopies. While we sat in tandem, one pilot in front and the other in back, we had separate canopies which were hinged behind our heads and pivoted forward, to the closed position. The canopy unsafe light extinguished and my master caution panel was blank, no red or amber lights. I pushed both throttles to their first forward stop and watched the gauges for both spin clockwise to 100% rpm and 600°C exhaust gas temperature. Satisfied, I released the wheel brakes and pushed the throttles all the way forward to light the afterburners. With a kick in the rear we leapt forward.

Decision speed, the speed before which we would abort and after which we would continue the takeoff, was around 110 knots. The airplane could lose an engine at that speed and still accelerate to around 140 knots to allow rotation and climb out about 160 knots. I suffered hundreds of engine failures in the simulator but the nearest thing in an airplane I had seen was an afterburner nozzle failing full open, reducing the engine to zero thrust. We didn’t practice engine failures on takeoff in the airplane; that would be very risky sitting in front of two afterburners. But I digress.

That’s where we were that day: half the runway behind us, half in front; the AB shooting two orange flames of thrust behind us; 100 knots of speed with the indicator winding itself higher nicely, and a black dart flying right at us. The black dart just missed the canopy on my left and the next thing I saw was a huge ball of fire shooting in front of the aircraft and the master caution panel on the instrument panel lit up like a Christmas tree. The loud explosion muffled quickly, only to be replaced by the “beep, beep, beep” in my ears, the aircraft telling me it was unhappy.

“What was that?” Wortham asked from the back seat.

“I think it was a duck,” I said.

I pulled back on the stick and pointed the nose skyward. I retracted the landing gear, and kept the thing climbing.

“Are you sure it was a duck?”

“No, sir. But it looked like a duck.”

“Well,” he said, “keep flying.”

We had 190 knots in no time, I slapped the flap handle up.

“Willy Two One,” I pressed the switch on the right throttle while trying to keep my steeley aviator's voice calm and, well, steeley. “Declaring an emergency, one engine shut down, request wide right downwind pattern for immediate landing. Roll the trucks.”

“Approved as requested,” the tower answered, “you can pull up closed if you want.”

“Left engine is seized,” I heard from the back seat. Sure enough, it was at zero percent and the left system hydraulics were at zero as well. We were lucky we got the landing gear retracted.

“No thanks,” I answered, “we need the pattern for the landing gear.”

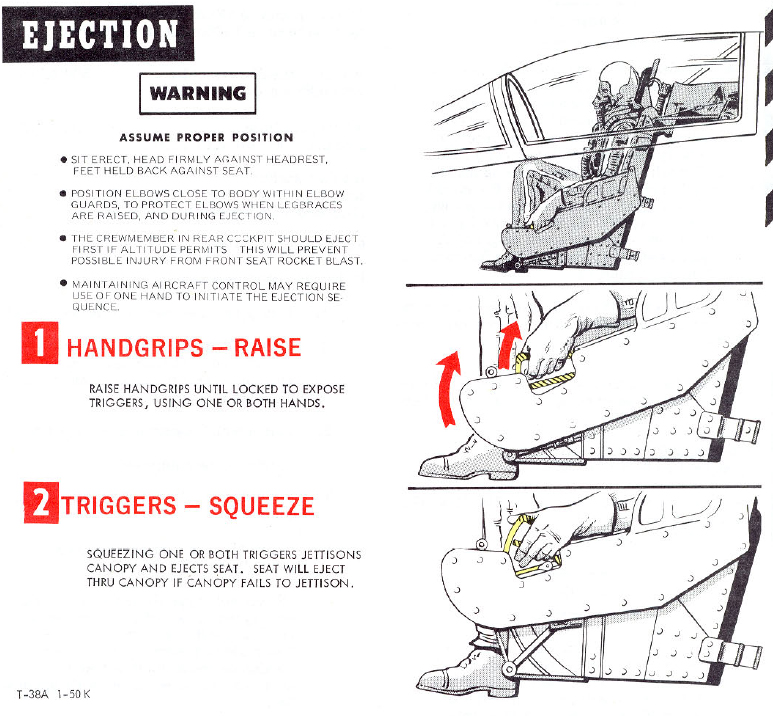

It probably took about ten minutes to fly that wide pattern. We extended the landing gear using the emergency system and talked about ejection. With one engine left the procedure would be to eject if that one failed. The airplane could not be landed without engine power, it could not be “dead sticked.” The flight controls were hydraulically powered and with both engines shutdown the aircraft could not be controlled. Even if both engines were windmilling, spinning in the wind, once decelerated below 190 knots the aircraft could not be controlled.

As I banked right and looked up to see the runway, my eyes hit the metal bar above between the windshield and the canopy. It was right in line with my knees and if I had ejected, I would be leaving those knees behind. I was determined to land.

Lined up on final everything was pretty calm and quiet. I looked at the three landing gear lights and the flap indicator over and over, they were okay. Airspeed? Okay. Engines, well, engine. Okay as well.

“Maybe we lost a bearing,” I heard from the back seat.

“It was a duck,” I said.

“It wasn’t a duck.”

The landing was uneventful, just like every single-engine landing in the simulator. Two months previous, when I had the AB nozzle failure, the other three airplanes gave me priority and I led the group back. The three airplanes, six other pilots watching my every move was more stressful than the landing. This time, it was, well, duck soup.

I started to raise the nose for a steeley-eyed fighter pilot aero braking, but then thought better of it. Get the airplane stopped. The fire trucks were waiting at the end of the runway, I pulled off and stopped. We both popped our canopies and dropped our oxygen masks. The smell was overpowering.

“Roast duck,” I heard from the back seat.

“Yeah.”

They towed us back to base operations, us two pilots sitting in a Navy jeep behind the broken bird and procession of fire vehicles. Of course we had collected a crowd by this time; if the entire base didn’t see the fire ball on takeoff, they were sure to have seen the black plume of smoke as we limped back to land.

A gaggle of Naval aviators — Air Force pilots congregate in "flights" while the swabbies collect in gaggles — waited for us just to talk and second guess. “Why didn’t you pull up to a tight pattern to get the thing back on the ground as soon as possible?”

“I only had one engine left,” I said confidently, “I wasn’t about to subject it to any G-forces. Besides, I needed the time to emergency extend the gear.”

They were not impressed. “That’s not how we do it in the Navy.”

Lieutenant Wortham called back to the base and was told two solo birds were headed our way so we could take one back. We had a few hours to hang out and walk to the Officer’s Club. Wortham was worried about walking around base hatless, his pristine flight cap was sitting on his desk back in Arizona. I took my hat off and tucked it into my pants pocket.

“Maybe we can fool these Navy toads into thinking we Air Force guys are too cool for hats.”

Wortham smiled for the first time that day. “Naval aviators,” I continued, “they would be dumb enough to pull up closed with an engine on fire and about to seize.”

He slapped me on the back. “Damned straight,” he said, “fly the airplane first.”

“Yes, sir.” I said.

“Call me Skip.”