There is an old saying in aviation: "You can never have too much fuel." In the Air Force we added to that: "Unless you are on fire."

— James Albright

Updated:

2014-06-05

Since then I've added several other caveats but the bottom line is this: fuel belongs in the tanks, in the engines, and out the tail pipe. Our Boeing 707's were filled with electronics and antennas which emanated electrons. Electrons and fuel? Not good . . .

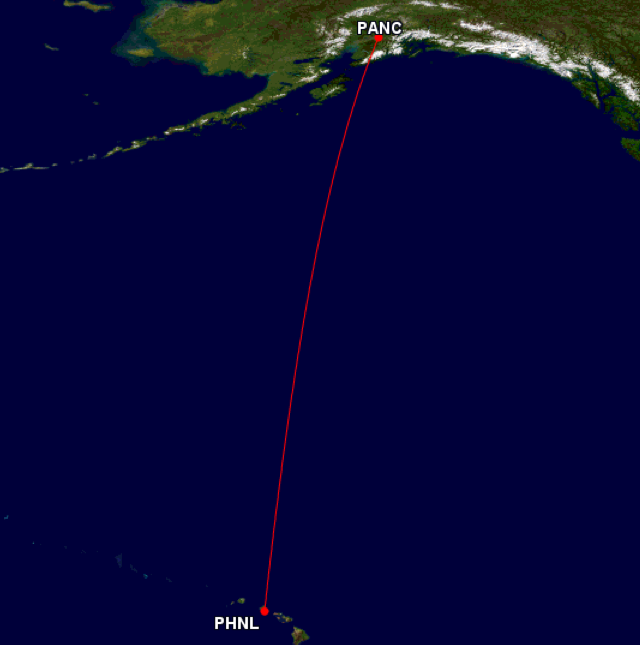

It was a plum assignment, flying a plum aircraft, in a plum location. And my first crew was a plum crew. It just couldn’t get any better. The mission was to fly the guys who controlled the U.S. nuclear submarine fleet, USCINCPAC. That’s United States Commander in Chief, Pacific to us Air Force types who don’t speak in elongated acronyms like the Navy.

The airplane was plum too. We had four EC-135J's. These were technically Boeing 717’s, but the FAA gave them the Boeing 707 / 720 type rating. They were a bit shorter than the airline version of a Boeing 707 but many of the true Boeing 717's of the day, such as the C-135B, had greater range. Not us, we were heavy with electronics.

Location? I was flying five miles from where I grew up. My family still lived in Hawaii and so did the Lovely Mrs. Albright’s. It was great.

And now the crew. The squadron was very senior, lots of old pilots and navigators. I got assigned to the youngest, the only one led by a mere captain. Captain Nick Davenport. An easier going aircraft commander I could not have asked for, but he seemed to know his stuff too. A perennial target of the Air Force “Fat Boy” program, Nick loved to eat. Me too. He promised me an Alaska King Crab dinner once we got to Anchorage. While I was looking forward to that, I was also looking forward to a long trip from Point A to Point B.

It was late at night when I took my first stroll to the back, where the lavatories are. From nose to tail I first had to pass by the galley, where the steward was chopping vegetables and offered me a cookie. Then came the communications suite where the radio operators ignored me and I had to stifle a cough from the thick, dense cigarette smoke. Next came the passengers. The admiral was on the phone and most his staff was pouring over big, thick, books marked “TOP SECRET.” Then came the aft section where our crew chiefs, security police, and extra crew were. They were all asleep.

On my way forward the steward handed me a tray. “You mind giving that to the captain, lieutenant?”

“Sure,” I said. It was a cheeseburger. A real cheeseburger freshly cooked. This was the life.

I nestled myself back into the seat and busied myself with my fuel logs as Nick devoured his meal. Mine would soon follow. We didn’t have much to do up there. The radio operators handled all the oceanic communications and the navigator did all the navigating. Major Ruddy, “Rudder” to his crew mates, programmed the inertial navigation systems – INS – and the airplane followed.

Our meals finished, Nick pulled out a stack of papers. “You do crossword puzzles, boy?”

“Now and then,” I said.

“I photo copied twenty of them,” he said, handing me one. “Last one done buys the first round tonight.”

We spent the next few hours doing crossword puzzles. Every now and then Rudder would bark “Hey, speed,” and Nick would nudge a throttle or four aft. But other than that, we paid no attention to the airplane.

It was about 2200. The INS by my left knee – I never had my very own INS before – reported we had just had crossed 41° North and that half the distance was behind us and half was in front of us. That isn’t a big deal and we didn’t compute “Equal Time Points” in four engine jets back then, it just wasn’t important to us. But I noted it just the same.

“Hey captain,” the engineer came forward and sat just behind us pilots. “We got fuel in the bath tub.”

“How much fuel?” Nick asked.

“A couple of inches.”

Nick thought for a few seconds. “Get a couple of crew chiefs with fire extinguishers, and position them just forward. Tell them to stay there. On your way back tell the commos to put out their damned smokes and let the pax know we are going to cut all electrical power back there in sixty seconds.”

“You got it, captain.”

“Bath tub?” I asked.

“It’s the area under the main floor all the way aft,” Nick explained, “it’s kinda shaped like a bath tub so that’s what we call it.”

“So that’s just behind the aft body fuel tank,” I thought aloud, “the fuel can be coming from there.”

“The fuel can be coming from anywhere,” Nick said, “everything runs aft.”

“Captain!” a new voice bellowed. I look back to see one of the Navy guys, a commander which made him a lieutenant colonel in Air Force terms. In military terms he certainly outranked us both. “What’s this about you cutting electrical power?”

“I have to sir,” Nick said, “in another thirty seconds.”

“You can’t do that, captain. The admiral is on the phone with the Pentagon, this is a national security priority two alpha call.”

“Twenty seconds, sir.”

“I am ordering you, captain, you got that?”

“Ten seconds, sir.”

“I’ll have you fired!”

Nick looked at me. “I’d rather be fired than dead, how about you?” I nodded.

“Who the hell do you think you are, I just gave you a . . .”

Nick reach up to the two switches marked “cabin power” and flicked both down to “off.” The back end of the airplane went dark and there were muffled voices followed by flashlights.

“What in the hell is going on here?” It was clearly the admiral’s voice, getting nearer.

My vocabulary is today what it is because of the many choice adjectives I learned that night. The admiral was inconsolable until the flight engineer returned to the cockpit, reeking of jet fuel.

“Excuse me admiral,” he said as he pushed his way forward, “I got to talk to the pilot.” The smell was overpowering. “Captain, we definitely got fuel back there. The only reason it isn’t getting deeper is it found a way out the ass end of the airplane. I think we are trailing fuel now.”

With that the admiral left the cockpit and we didn’t hear a peep from him or the other passengers for the rest of the flight. Nick and I reviewed ditching procedures and weighed the benefit of descending in case the whole airplane was going to ignite. As best we could tell, our fuel loss was no more than 500 pounds an hour, so we could lose another 2,000 pounds in the four hours we had to go. We had enough fuel but not a lot to spare. In the end we decided to stay at altitude and take our chances.

We landed at Anchorage with a full parade of fire trucks. The next morning our crew chiefs found the hole in a forward fuel tank. It was streaming fuel the length of the fuselage, past all the cabin electrics. Nick never got a commendation or even a thank you from any of the Navy passengers. Among us Air Force types it was understood that it was all part of the job.