I've only lost cabin pressure twice. The first time was really a self-inflicted wound. The maintainers found a problem with one of the airplane's outflow valves so our secret was safe, but still there were lessons all around. I think I knew the aircraft systems pretty well but that wasn't the lesson I needed.

— James Albright

Updated:

2014-06-25

With all of three years as a copilot and three months as an aircraft commander, the aircraft captain, the lesson I needed was crew leadership. I wrote this thirty years ago and yet the lessons seem more pertinent today than ever . . . this was the day I realized I was "the old man."

“Copilot.” For many with experience in multi-place cockpits, the term constitutes a final destination, the pinnacle of a flying career that led to an airplane requiring more than one pilot. For others, it was a midpoint, something they did along the way to where the action really was. And, for a final few, it was the starting point to a long career in the left seat leading crews. No doubt about it, option three of that trifecta is where I want to go.

The problem, of course, is your first time as a copilot you have no idea which of those three paths your fate will lead you. Even when you first become a captain, what we in the Air Force call an “aircraft commander,” you have no idea how long your tour in the left seat will be. That’s where I found myself when I got assigned my first copilot. I was determined to be the best aircraft commander the United States Air Force ever saw. I would be a great pilot, of course, but I would inspire the crew with my leadership. I would listen to all view points, consider all opinions, and then I would decide. I always hated crew commanders who never listened to their crews. I would be different. My copilot would count his blessings whenever he talked about getting assigned to Captain Albright's crew.

Lieutenant Jim Dellums was the Air Force poster child for what everyone wants to see in the cockpit. Tall, clear blue eyes, baritone voice that spoke volumes in a few words where others needed paragraphs. Privately, only to the lovely Mrs. Albright, I called him Steve Canyon.

He flew a good airplane and seemed to know his stuff. And he always made his boss look good. How? Well, let me tell you. By the time he showed up on my crew I still had the squadron’s record for the worst copilot landing ever.

. . . Two years previous . . .

“Copilot, Radio Two.”

I got a call on the crew interphone following the landing. It was one of the three radio operators.

“Go ahead radio two,” I said, a bit timidly, even for a lieutenant.

“Sir,” he said, “the integrity of the water tight doors is maintained.”

There were howls of laughter behind me. I looked at the captain, who managed to stifle his own laughter.

“Sergeant Phillips,” he explained, “used to be in the navy and that’s what he would have to say if the sub ever bottomed out on the ocean floor.”

. . . Back to our story . . .

For two years, no other copilot could top that landing until Dellums showed up, just a month ago.

The landing looked good until the ground effect disappeared below our wings as we flew over the hot concrete of Hickam Air Force Base and then over the cooler grass of the golf course just short of Runway Eight Left at Honolulu International. We hit so hard the door to the aft lavatory fell off its hinges.

I took control of the aircraft and scanned the engines to make sure we hadn’t lost any of them. After I counted engines I counted my blessings. No longer would they be talking about the integrity of the water tight doors. Now it was the aft lav door. I was Lieutenant Dellums' biggest fan.

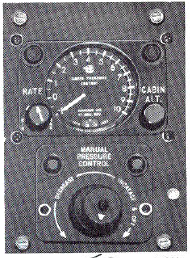

That was then and this was now. We were flying up the coast of California with a minor pressurization problem: the cabin would vary a couple of hundred feet every few minutes, causing a pop in the ears now and then. The system was pretty basic on the Boeing 707. The four engines pumped air into the cabin and three outflow valves, one for each wheel well, would permit just enough air to escape to keep the cabin pressure comfortable. At least that is what Boeing had intended.

We knew that the engines wouldn’t pump enough air in at low power setting so we had a modified engine power schedule on descent. We knew, also, that there were times in cruise flight that the automatic system would give up and we could fool it into keeping more of the air inside than out by playing with the manual system. Some of our pilots would do that and swore it made a difference. It always seemed to me to be too great a risk for too little a reward. I left the system alone.

Copilot Dellums had spent a month flying with another crew when I was on leave and seemed to have some new tricks up his sleeve. I glanced over to see him fiddling with the pressurization system over his head.

“Whatcha’ Doin?” I asked, trying to be casual about the whole thing.

“I heard from the other copilots,” he said while fiddling some more, “that you can move the manual pressure control five or ten degrees counter clockwise and lower the cabin a good five hundred feet.”

“Isn’t that an emergency procedure?” I asked.

“No,” he said, “it works.”

I sat back and said nothing. In my vast career as a copilot I always hated the aircraft commanders who would automatically tell me what I was doing was wrong, refusing to listen to another point of view. I wasn’t going to be one of those aircraft commanders.

Still, I thought, we were at 35,000 feet and our time of useful consciousness without pressurization would be measured in seconds, not minutes. The manual system required the copilot’s finesse on a very small control knob where as the automatic system was motors, rheostats, and pulleys that removed all human input. The automatic system was used every single flight, the manual system almost never. What can go wrong? What indeed.

I am writing this the month after and it is already getting jumbled in my head. I think the first thing that happened was the air getting sucked out of my chest. Or maybe it was the air crystallizing in front of me into fog. One or the other. The noise came after. It was a loud roar.

Our pilot oxygen masks were above our heads and I reached for mine instantly. I gasped at the cold, sterile air. The next step was to hit a few interphone switches to establish communications with the cockpit crew but that isn’t what I did. I reached, cross-cockpit, over the copilot’s head to rotate the manual pressure control full clockwise, restoring automatic control.

The air in my lungs was restored, the fog subsided, and things were quiet again.

“Don’t touch that again,” I said to Dellums, “without asking me first.”

“Yes,” he said meekly, “sir.”

Nobody seemed to be injured and it seems some of the passengers in back thought it was fun. I wrestled with how I was going to report this. It was fortunate we were landing at a Sacramento Air Force Base with a similar aircraft, the WC-135. I could think up something to tell home base while the mechanics here could look us over to make sure we didn’t break anything.

What they found was the nose outflow valve was caked over with tar and nicotine, years of smoke exhalations from our communications crews sitting right on top of the thing. The maintenance team said the outflow valve, for some reason, was sealed shut until the manual system commanded it full open. The manual motor was stronger than the automatic motor, it would seem. They cleaned the valve and cleared us for flight.

So, a week later, we had a war story to tell and Lieutenant Dellums had his first “Don’t ever touch that admonition from the old man in the cockpit. I was twenty-seven.

Dellums says he now understands systems better and that playing around with something in the emergency procedures section of the flight manual is best left for the simulator or real emergencies.

Me? I learned that being a crew commander isn’t a popularity contest and sometimes you have to squash creativity for the sake of safety.

Good lessons for both of us.