I can't speak for any "classically trained" instrument pilots, but my experience has been they hand you an instrument approach plate and you fly it down to minimums with possibly hundreds of people sitting behind you trusting that you know what you are doing. In the safety profession we call this "assumed risk." They assume you know what you're are doing. You assume the clowns that drew up that instrument approach plate were paying attention in instrument procedures school.

— James Albright

In the Air Force we grew up with Department of Defense plates and in my part of the Air Force we kept DoD plates, Jeppesen plates, and who-so-ever's plates that we could find. We would rely on the plates that got the most use, rationalizing there is safety in numbers. But in the waning days of the cold war even that wouldn't work. Fleeing Soviets and ex-soviets would make off with instrument approach systems and people started dying.

It really pays to look at every approach plate with a jaundiced eye. The person who drew it may not have been paying attention in school. Things may have changed since the day it was drawn. Take a hint from a motorcyclist's credo: fly as if everyone else is out to get you. Was I always so paranoid? Perhaps. But it really started when I was an Air Force squadron commander with one-hundred crewmembers flying into the UFFR — The Union of Fewer and Fewer Republics — in really crummy weather. That's when I learned about flying . . .

Updated:

2014-04-16

Instruments on a non-instrument napkin

As told by Captain Rorie Fitzpatrick, C-20A copilot

"Batajnica," Lenny repeats, almost yelling into the phone. "B-A-T-A-J-N-I-C-A. They say it is a well-known airport on the outskirts of Belgrade. Okay, I'll hold."

I double check the large Eastern European Jeppesen Approach book, the smaller DOD version, and the British approach plates I found underneath the counter. We had to cancel our London sightseeing to come in and re-plan the remainder of our trip. Instead of Austria, our passengers now want to go to Serbia. The Air Operations boys back at base insist this airport is okay for us to fly to, but don't know where any instrument approach plates are. There are none published in the Jepps and certainly none in our DOD books. We've been looking for any kind of approach plate for over an hour now. Our congressmen passengers insist the former Russian Mig Base is the new, large metropolitan airport set to take over as the "Gateway to Serbia."

"Try looking under Beograd," Lenny suggests, still holding the phone to his ear.

"Already did," I answer, ready to give up the hunt.

"Okay, connect me." Lenny cups his hand over the phone and explains, "they are going to connect me to the American Embassy in Belgrade. They say the Serbian Air Force produces the only approach plate and nobody carries it but them."

"I didn't know Serbia has an Air Force."

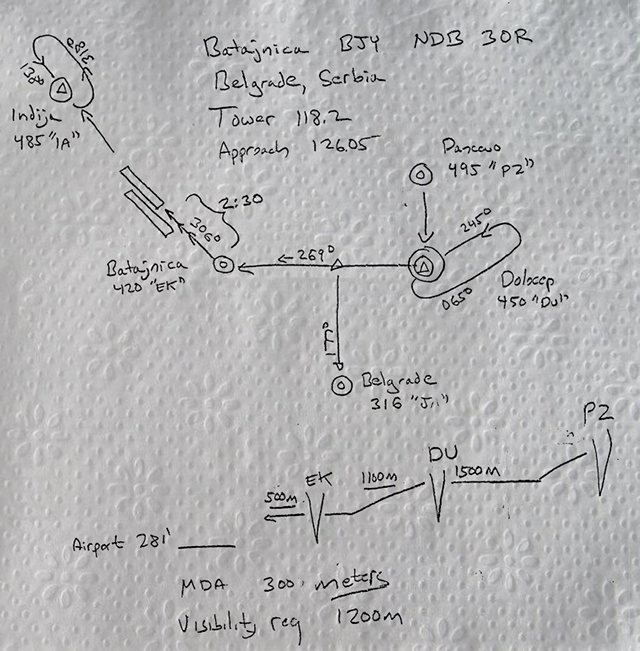

After an hour of trying, we have Lenny's hand-drawn approach plate for the NDB into runway 30R of Batajnica Airport. The embassy doesn't have a fax machine and this is the best we're going to do. The American at the embassy isn't a pilot, but gives the right answers to all our questions. The approach plate clearly says "ICAO" on top, meaning the approach is blessed by the International Civil Aeronautics Organization.

"Are we allowed to fly an approach in weather using a plate drawn on a napkin, Lenny?"

"No sweat, Rorie." Lenny smiles that goofy smile of his and laughs, "you know what Colonel Parent would say? 'Buddy, I want you to be a good captain and just fly the damn napkin.' "

"Yeah," I agreed, "he'd say that with an F-bomb or two thrown in. But he's gone. What would Colonel Albright say?"

"Colonel Parent, Colonel Albright, what's the difference? They are both 89th toads who don't know the meaning of the word 'no.' Besides, has this squadron ever canceled a mission?"

I copy Lenny's napkin so I will have something to look at as he flies the approach. The regulation says we can fly using any ICAO host nation's approach plate and I have done that once or twice before. Flying off a napkin will be a first.

This is the kind of approach that makes most pilots sweat. You have to fly to a non-directional beacon at a safe altitude, turn, descend and fly to another NDB. If you manage to do that without getting lost, you make another turn, fly to a third NDB, and descend again. Finally, you are low and slow, looking for the airport. If you spot it, you guesstimate the descent and land. To make matters worse, you have to do this flying your altitudes in meters! Our altimeters are calibrated in feet.

Lenny, one of those natural pilots you hear so much about, wants to fly the approach. I didn't fight that decision for a second! He gives me the "I could do this in my sleep" look and studies his napkin. He's got an unlit cigar perched between his lips as he nudges the throttles aft. Our Gulfstream obediently increases its dive into the thickening Serbian pea soup.

The flight engineer calls out "Radio Altimeter?"

I check my hand-drawn approach plate and read, "300 meters."

"What's that in dog years?" Lenny asks.

I check the chart in my checklist and run my finger down the Meters-to-Feet column. I simultaneously set my radio altimeter and say "Nine hundred and ninety."

Lenny sets his radio altimeter and gives me a knowing wink. We cannot descend lower than 990 feet without first gaining visual contact with the runway. As the copilot, spotting the runway will be my job.

I've always hated being a copilot. Even in the C-141 I couldn't adapt to the role with the easy grace expected of new pilots. Being a woman has nothing to do with it. My personality just tells me I have to be in control. Now I'm watching "Mister Natural" fly us into a former Eastern Bloc nation using an approach plate he drew on a paper napkin. For the hundredth time, I scan the horizon line of my Attitude Director Indicator to make sure Lenny has the situation under control. The airplane's nose is one degree above the horizon and rising.

Our airspeed is a steady 320 knots, as it should be. The Instrument Vertical Velocity Indicator now shows us descending at 2,300 feet per minute. The IVVI is about right for this altitude, speed, and distance remaining. Now the nose is four degrees nose high. What the hell? His ADI shows the nose at two degrees low, as does the emergency attitude indicator on the glare shield.

"Lenny, I think I'm losing my ADI."

"Som beetch, if you aren't," Lenny agrees. "So what does that mean to me?"

I think back to the regulation. "You are now limited to flying no lower than 400 feet with one mile visibility. Our mins are higher so you can still go to the published minimums."

"Good girl," he smiles.

Don't you call me girl, I say to myself.

Lenny isn't a chauvinist pig, I know. He's just a pig. Air traffic control hands us off to Belgrade approach, who clear us for the approach. "Radar out of service," the controller says, "clear to Papa Zulu to commence approach, Runway 30 Right."

"Wilco," I answer, setting the radio frequency for the Papa Zulu NDB. The needle waivers unsteadily for a moment and then settles on a heading about thirty degrees to our right. Lenny dips the right wing down fifteen degrees and the airplane turns smoothly towards the NDB.

Just as Lenny levels our wings the NDB needle goes crazy and we lose Papa Zulu for good.

"Where's my damned NDB?" Lenny barks.

"We lost Papa Zulu," I say to Belgrade Approach Control. "Say the status?"

"Is okay," Belgrade lies, "is no problem. Clear to Delta Uniform next."

That checks with our hand-drawn approach plates. I dial the frequency and the NDB needle settles on another 20 degrees to the right. We can turn right, but what about obstacles?

"We're off the procedure, get these points into the INS."

"I don't have coordinates, Lenny."

Lenny turns cautiously to the right. Cautiously? We are in the weather now. Blindly. That's the word I want. Lenny turns blindly to the right. I key the mike again and ask Belgrade about the terrain between us and Delta Uniform.

"We have no radar," the controller calmly answers. "Clear to Delta Uniform."

The approach is designed to take us from one NDB to the next to keep us clear of any terrain or other obstacles. We are getting vectors from a controller with no radar. How does he know we are okay for the next turn? As Lenny said, we are "off the procedure" and on our own.

We pass Delta Uniform and Lenny asks, "What's my next point and altitude, Rorie?"

I check my drawing and convert the 500 meter step-down altitude to feet. "Clear to turn right to Echo Kilo, and descend to 1,640 feet. This is your final approach fix altitude."

I hate flying uneven altitudes. All pilots like even numbers. Our needles line up better that way. Who can fly 1,640 feet? Lenny levels the airplane off at 1,700 feet and my inner psyche tells me I'm either 300 feet too low or 200 feet too high.

I can see the accident report now. "A chain of poor decisions," it will say, "any one of which would not result in a mishap; but in sequence, combined to place the crew in a position from which they could not recover." We started with the napkin approach, then lost an ADI, then found out we don't have radar coverage, then lost the first NDB. Each step of the way Lenny decided to press on. I supported every decision because each was correct. Now Lenny has his hands full just flying the airplane and I'm having to work my butt off just to keep up.

Passing Echo Kilo Lenny pushes the nose forward and commands, "Landing gear down, complete the Before Landing Checklist, I am descending to our minimum descent altitude of 990 feet." Passing 1,100 feet Lenny adds power and pulls the nose of the airplane up two degrees. "Eyes open, please. Tell me what you see! When do we go missed?"

"Missed approach at two minutes, thirty seconds past Echo Kilo," I answer from memory, keeping my eyes glued to the fog in front of us. A minute and thirty seconds to go. The regulations say we must go missed at the missed approach point, which is way too close to the runway. Even if we saw the runway at that point, we'd be too high to land. At 990 feet, we don't have a chance in hell of landing unless I spot the runway at least 2 miles away. That's about fifteen seconds from now. No, I guess we can go a little closer. How does that formula work?

"Two minutes, Rorie, anything?"

"Negative," I answer, straining my eyes harder.

"Wait!" I add. I spot a few lights, spaced evenly apart on either side of a road. No, a runway. "Runway in sight, twelve o'clock," I report, "you will need a steep descent."

Lenny looks forward, spots the runway, chops the throttles to idle, and pushes the nose over. We plunge through the fog and our view of the long runway improves dramatically. We are high, but the runway is long.

"I'll land half-way down the runway," Lenny says, shallowing his dive. "Make sure the gear and flaps are where they need to be, finish the checklist, we're landing."

The main wheels lightly touch the runway and Lenny pulls back on the reverse thrust levers. The passengers clap and cheer as the noise of the reversers announce our arrival. Lenny looks to me and smiles, "Cheated death again."

C-20A cockpit, aircraft 83-0502 later became NASA aircraft N802NA, photo by Matt Birch, http://visualapproachimages.com