Just because you've crossed the north Atlantic a few times doesn't make you an international pilot and no matter where you come from and where you are going, it helps to approach each new situation with a little paranoia. Okay, there is my standard introduction to any international pilot who appears to be taking things a little too easily. Sure, in the ten years since this has been written, flying in France has gotten easier. But every now and then they revert to old form. Here is a short story that illustrates all of that.

— James Albright

Updated:

2013-07-18

It was one of those flights from somewhere in the U.S. to somewhere in Europe where my marching orders were to make sure the passengers were happy and the other pilot learned about the somewhere in Europe. Once we established our position report / time / plot routine I dug out the Jeppesen State Pages and read the air traffic control, emergency, and entry requirements pages; though I had done so just a few weeks prior. As I finished a section I handed it to Jarod and said, “read this.”

I had been doing this for many years, maybe twenty now, and the reaction from the other pilot varied from “hell no” to “yes, captain instructor, anything you say.” Jarod was in the middle and appeared to read but didn’t ask any questions. “I know this stuff,” he said. I knew any pilot flying into France for the first time without questions wasn’t paying attention.

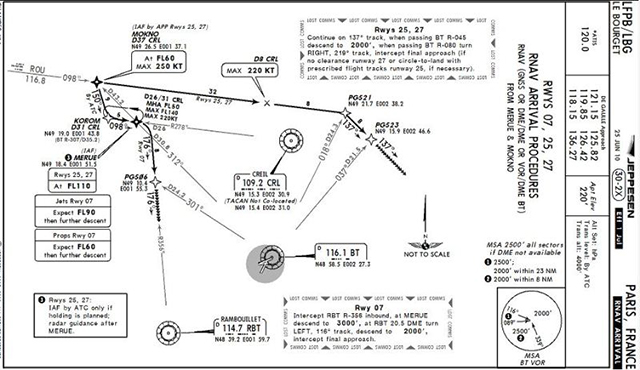

Some of the best lessons in life, I knew, were hard learned. So I left Jarod to his own and continued my foreign country routine by reading each arrival procedure and pronouncing the names aloud. “Caen Four Echo,” I mumbled, “Devaulle Four Echo, Dijon Five Whiskey . . .”

“What are you doing?” Jarod asked.

“I like to pronounce each procedure,” I answered, “no matter how many times I’ve been there it helps to sound it out. That way if you hear it on the radio, you’ll have a hint about what they are saying.”

“You’re a bit paranoid,” Jarod said, “aren’t you?”

“Yes,” I said. I’ve always been paranoid about flight procedures. “The international language of aviation is English, as you know, but not everybody speaks English in English. The French are some of the worst.”

“I’ve always found that if you speak politely and slowly,” Jarod said, “the foreign controllers will work with you. You just need to have more patience, James. And being polite wouldn’t hurt.”

“Polite?” I laughed.

* * *

1985, twenty years previous. I was in a French restaurant on the Mediterranean coast and fish seemed to be the meal of choice. I asked for a glass of Cabernet.

“Would messieur be happier with a chardonnay or perhaps a muscat?” The waiter asked.

“No thanks,” I said, “a Cabernet will be great.”

“But messieur, en France we prefer a white wine with the poisson.”

“That’s okay,” I assured him, “I don’t like white wine. The Cabernet will be fine.”

“But messieur,” he persisted.

“You going to eat this meal for me?” I asked.

“Of course not, messieur, I was only suggesting. . . “

I ended up with my fish and the Cabernet. My table mates suggested I inspect the meal carefully, the waiter probably spat on it.

* * *

We ended up on the east side of the English Channel without incident. It was about ten p.m. and traffic was light. “You should be able to get ATIS,” I said to Jarod, “turn the squelch off and see if you can get us a head start on Le Bourget.”

“It sounds like runway seven,” Jarod reported, “but I think the report is over two hours old.”

I toggled the radio and though weak, it did sound like “point rouen, deauville four echo, runway seven” was being called.

“That doesn’t make any sense,” I said to Jarod, “winds are supposed to be calm and the only reason they would use that runway was if the Germans were crawling over the Maginot Line. Ask Center to confirm.”

“But of course,” Paris Control replied, “landings are to the east.”

“Okay,” I relented, “set us up for runway seven. This is going to be a first.”

Jarod busied himself and filed away the unused approach pages from the Jeppesen binder.

“Keep those out,” I said, “I don’t trust them. It has been a while since it has happened to me, but sometimes they purposely set you up just to see if they can violate you. French bastards.”

Jarod shook his head, not in my favor I knew. “Paranoid,” he said, almost sotto voce.

* * *

1992, thirteen years previous. I was getting a check ride from the meanest Andrews sumbeech that stan/evil had to offer and he had already told me his objective was to knock me down a few notches. I had flown the aircraft from Andrews to deep inside Russia, and now from Istanbul to Shannon, Ireland. My copilot was getting zero stick time until the evaluator was satisfied that I passed or busted. In the case of the former, “co” would get a leg. In the case of the latter, mister stan/evil would take my place and I would be a passenger home. After ten legs, I was still flying.

“You going to revise your block time?” stan/evil asked, “I would if I were you.”

“No,” I said, “too soon to make that decision.” The book said I could revise it once but I had to do so no later than one hour before landing. The diplomatic status of our passengers bought us the right to overfly Austria and Switzerland — unusual for a military aircraft back then — and the timing wasn’t working out. We accepted a few too many shortcuts and the computers said we were twenty minutes early. Our tolerance was five seconds.

“Only a wimp waits till the last minute,” stan/evil said, “I may have to bust you on style points alone.”

“You do what you have to,” I said, “I’m waiting.”

“Fine,” he said, “I’m going to the galley.”

With that, he was gone. He was right, of course, we had to declare our block time right before takeoff and any adjustments were frowned upon. But we were allowed one update and it had to be done as soon as possible. Everyone did it. Not me. I had never yet had to adjust a block time and didn’t want to start now.

“Why you waiting,” the copilot asked, “I can see losing two or three minutes. But twenty?”

“We still have France,” I answered, “I don’t trust them.”

Leaving Switzerland the copilot checked in with French Air Traffic Control and they answered immediately. “SAM Six Oh Two, Reims Control. Verify you are sierra tango sierra.”

“Affirmative,” the copilot answered, “Special State Status.” The STS was something we filed regularly, given the nature of our passengers, and most countries accepted that knowing they would get reciprocal respect. Not the French.

“Say your country of origin,” Reims Control replied.

“The United States,” the copilot answered immediately.

“We’re screwed,” I said over the interphone. The copilot looked at me with question mark eyes.

“SAM Six Oh Two,” Reims said, “turn left two seven zero.”

“Roger,” the copilot replied, “left turn two seven zero. Say point of vector?”

We never got a reply. We tried every frequency from Reims, to Paris, to Bordeaux, and finally to Brest Control. Nobody in France would talk to us. I heard this happens now and then, the French were upset with a U.S. diplomatic flight transiting through their airspace but not stopping. Now I had first hand experience. As we headed west I watched the computers add time to our Ireland ETA. It was working in my favor.

With France behind us we found a frequency for London Control.

“SAM Six Zero Two,” the controller said, “we were wondering where you were going to pop up. Welcome to the found, turn right direct Shannon.”

The copilot programmed the inertials and the airplane banked right. The ETA display updated itself as Colonel Stan/Evil reappeared from his hour flirting with the flight attendant. “I’m going to enjoy busting you, Haskel.”

I looked down at the inertials. We were on time.

“You are the luckiest son of a bitch,” mister stan/evil said.

Stinking French cost us twenty minutes of jet fuel and saved my check ride.

* * *

We were given our descent into Paris and instructions to call De Gaulle Approach. “Yes, yes,” they assured us, “Le Bourget is landing to the east, Deauville Merue.”

“That checks,” the copilot said, “Merue is for runway seven.”

“Well,” I said, “there is a first time for everything.” I started to relax. The weather report was two hours old and we were landing on an unusual runway. But everyone said it was okay. “Contact De Gaulle one two five eight two.”

Jarod checked in as instructed. “Turn direct Mokno,” approach control said.

“Mahk-what?” Jarod asked.

“Mokno,” I said, “is due east, I’m turning zero nine zero, program the two seven arrival and catch up with me.”

Jarod found the chart and quickly programmed the arrival. One frequency later they finally admitted we would be using the usual arrival to Runway Two Seven. We checked in with Le Bourget Tower and landed.

“It’s almost like they were playing with us,” Jarod said, “how did you know?”

“Lucky, I guess,” I said, “Mokno is for the other runway.”

“Geez,” he said, “it is almost like they were setting us up to fail.”

“No,” I said, “it’s exactly like that.”

“Bastards.”

I noticed Jarod started paying more attention to international ops that day. It is good when you can learn a lesson like that without breaking anything.