In 2009 I was starting my fourth job as a civilian where my primary role would be as a check airman. Though I had been on both ends of the evaluation routine many times, I liked to call it stan/evil. In the civilian world it was simply “check airman” and sometimes just “standards.” The new company was going through the check airman drill with the FAA and asked me to provide the number of check rides I had given over the years and the number was surprising. Looking at the number I told myself, “I’ve seen it all.” Several months later I gave my one-hundredth check ride and found out I hadn’t seen it all after all. Here then are my top five busts.

— James Albright

Updated:

2013-01-16

Number Five

Boeing 707 “Why do I need the Landing Gear?”

Honolulu, Hawaii (1985)

Your first bust as an examiner is supposed to be the hardest, but this one was actually pretty easy. I was an Air Force Captain in the jump seat giving a qualification evaluation to a new pilot in the left seat. The squadron’s chief of training was in the right seat. They both outranked me.

The ride was going okay, there was plenty to critique but nothing disqualifying until the full stop landing back at Honolulu International. They intercepted the glide slope and descended for landing with the gear still up. The rule book said it had to be down no later than the final approach fix or glide slope intercept. My only decision was how long to let them go. I decided on localizer minimums.

I tapped the right seat pilot on the shoulder and keyed my interphone mic, “put the gear down, sir.”

As we walked into the squadron both pilots chatted easily, even including me in the banter. I was consumed with the thought of having to bust my superiors and couldn't really participate in the post flight chat. I called the wing headquarters just to make sure I wasn't about to make a grievous mistake. "No decision here," my boss told me. Yeah, I guess the phone call was unnecessary.

Both pilots were stunned that I busted them — You mean we can’t land without the landing gear? — and the squadron appealed on their behalf. Of course the bust stood.

GIII “Block Times are Optional”

Ramstein, Germany (1994)

Block times mean different things to different Air Force pilots. In the real air force, it simply means landing at the appointed time plus or minus fifteen minutes. For a time at the 89th, it meant arriving at the red carpet no later than five seconds, no earlier than zero seconds from the promised time. We risked all for the sake of the block time, it was crazy. (They don’t do that anymore, saner heads have prevailed.) At my squadron in Germany, a block time was on time if you simply made it to the red carpet at the appointed time but never early and no later than five minutes.

The minus zero/plus five rule made sense to me: you didn’t want to arrive early because the VIP might be embarrassed if the greeting party required by protocol was absent. The five minutes gave us plenty of opportunity for success without the crazy 89th shenanigans I grew up with.

So there we were, a seasoned instructor pilot was in command and flying the airplane. Let’s call him Captain Dumbkof. In back we had the head of state for one of the new countries born from the UFFR — the Union of Fewer and Fewer Republics. The pilot was five minutes early.

As he begun his descent I had to ask, “How’s your block time coming?”

He did the necessary math and reported, “five early, sir.”

“Right.” Ordinarily I would never say anything during a check ride. But it wouldn’t do to embarrass the country for the sake of fairness. I waited for Dumbkof to adjust, but he didn’t. Passing 10,000 feet I asked again and got the same answers. Uber Dumbkof.

At the final approach fix I asked again and got the same bizarre answer. “Let’s do a right three-sixty,” I ordered, “that will kill four minutes. Then hard on the reverse, taxi slowly to the end of the runway for the remaining one minute.”

“Good idea, sir.”

I took away Dumbkof’s instructor status. I should have busted him to copilot.

Number Three

CRJ “Cleared Direct to Wherever I want”

Gunnison, Colorado (2001)

It was the first check ride I ever administered as a civilian and things could not have been more promising. We were flying a Canadair Regional Jet from Houston to Gunnison, Colorado on a CAVU day and in the left seat was the chief pilot for this corporate operation. In the right seat was a seasoned check airman. From takeoff to cruise everything was right out of the text book.

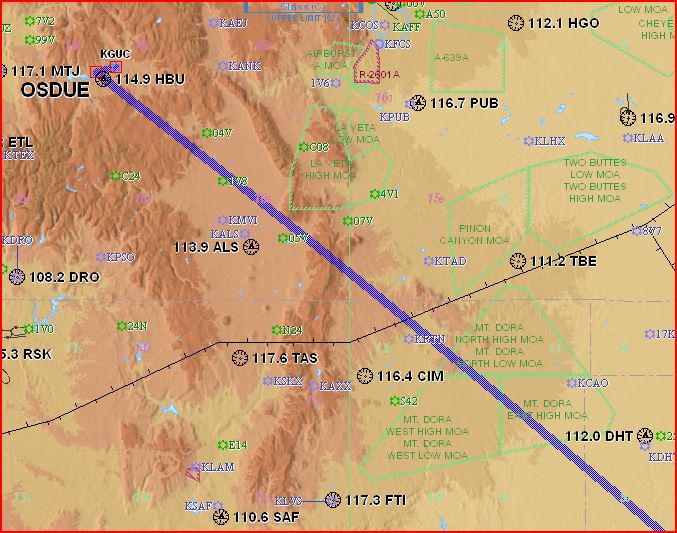

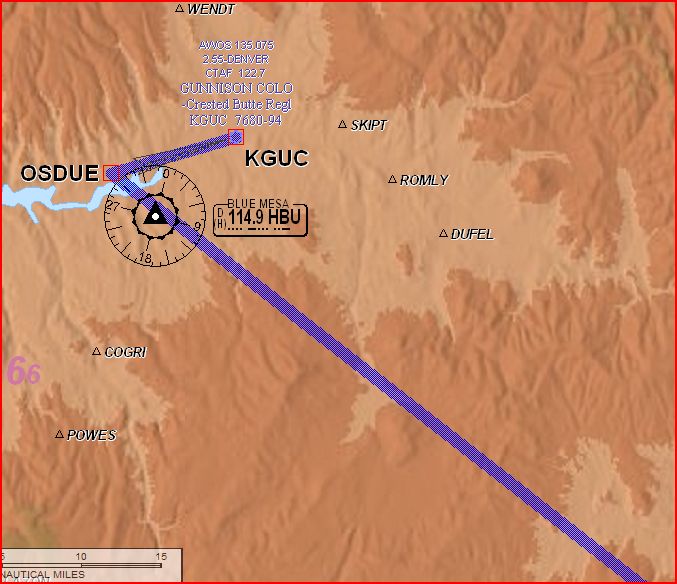

At top of descent, about one hundred and fifty miles out, the crew was cleared directly to the airport. I watched as the right seater programmed the ILS to runway six and direct to the final approach fix, OSDUE. Of course that wasn’t our clearance.

I did some quick math on my note pad. OSDUE was seven miles west of the field and we were approaching from the south east. At one-hundred miles even with a perpendicular approach we would only be a few degrees off heading. But as we got closer that would change.

At one hundred miles I pulled out my favorite examiner trick, asking a question as if I was really asking, just to get them to think. “Hey guys, was our clearance to the airport or the fix?”

“It doesn’t matter,” the king of the airplane barked, “we always do it this way.”

“If you want to go to the fix,” I said politely, “you could request that. Otherwise your clearance is to the airfield.”

The left seat tyrant unloaded with both barrels at me, telling me how unprofessional I was interfering with a fully trained and professional cockpit crew. He was going to make a few phone calls when we landed, by golly, and I would regret the day I got on his airplane.

I listened quietly to the dressing down I was getting, while watching the angle between our course and our clearance grew. I was starting to wonder what my legal obligation was when center called, “Say heading?”

The verbal tirade I was getting from the left seat paled in comparison to the tirade we got from Denver Center. Sometimes a check ride bust speaks for itself.

Number Two

Citation Ultra “Let’s Raise the Difficulty Level”

Louisville, Kentucky (2003)

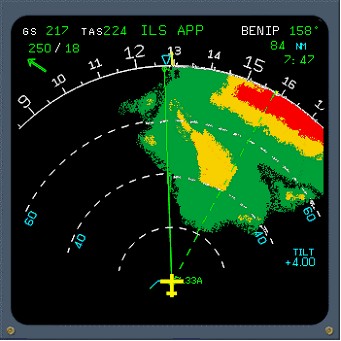

A few years later I was trapped in a Citation Ultra watching a very good captain and a very bad first officer navigate their aircraft between heavy rain cells and just south what looked to be bad news on the radar. The very good captain was doing a very good job keeping the aircraft headed the right direction with the help of what looked like a standard small aircraft autopilot. He programmed the thing to capture the localizer and it proceeded to do just that.

I was watching the aircraft bank gently to the left for what looked to be a good turn on course when a sharp updraft threw me against my shoulder straps and my tender skull an inch away from the ceiling.

When I looked up the aircraft had reversed its bank and was heading away from the course and towards the nearest red blob on the radar. We were about 1,500 feet above the ground and descending. The very good captain overrode the autopilot and turned the aircraft back towards safety. The very bad first officer just sat there, with his left hand resting on the center console. The very good captain took his finger off the touch control steering system — the button that allowed him to override the autopilot — and once again the aircraft turned away from course and towards certain peril.

I scanned the cockpit furiously, looking for the cause. I found it under the very bad first officer’s hand. He had knocked the autopilot aileron control to full right, causing the autopilot to ignore the approach course. A stupid design, one we had in the 707 many years ago.

I contemplated the pros and cons of saving the situation versus busting the very good captain because of the very bad first officer, when the very good captain found the errant control knob and fixed it himself. I decided to bust the very bad first officer and to give the very good captain a pat on the back.

“Please don’t bust him,” the very good captain said, “he’s the owner’s son.”

I could only answer one way: “You have to expect a few losses in a big operation.”

Number One

Falcon 900 “Single Pilot”

Vancouver, Canada (2009)

The one hundredth check ride was the worst; they were busted before they got off the ground but I didn’t know that until after we took off. I met the pilots at their hotel in Nantucket, both very pleasant fellows. The captain briefed me that the weather was okay from departure through destination, no worries. Both pilots had good airline resumes so I thought I was in good hands. I prefer to fly with pilots with long resumes in the military or airlines — growing up in a strict, standardized environment is a good thing. A pure civilian pilot can be just as disciplined and professional, but he or she has to work at getting there. Not many do.

I made myself comfortable in the jump seat for the six hour journey west, from Nantucket to Vancouver. The jump seat in the Falcon 900 isn’t the best, but it isn’t the worst either. I checked their paperwork and spotted the arrival forecast immediately as something less than okay: CYVR 191738Z 05004KT 1/2SM OVC002 FM190200 07002KT 1/4SM OVC 001. The destination airport was at minimums when we took off and would go below minimums when we got there. The alternate, Abbotsford, was just fifteen miles to the west but was practically clear. They violated company rules by taking off, but we would be okay at the alternate. As long as the rest of the ride went okay, I would make this a critique item but not a bustable offense.

Even with just over an hour to go, the two pilots were chatting happily, oblivious to the weather. Center called up and finally asked, “Vancouver airport is closed, say intentions?”

The two scrambled, papers flew, the weather was requested via data link, and the approach plate was examined. Finally center called in with more help, “hold at point WHATS, left turns, ten mile legs.”

I looked up to the FMS and watched the point pass behind us. The first officer swore an oath at the box and told the captain he would have to manually enter the point. I restrained myself from giving him a two keystroke answer to all his problems and watched him build the holding pattern from scratch. The captain, very smartly, commanded a manual left turn on the autopilot and hit the timer on his clock. Well done, I thought. Finally the first officer got the holding pattern done and was ready to tell the FMS to override the previous instruction. Just then the captain turned back to the point and saw WHATS in the box and commanded his FMS to proceed direct. The captain hit the final key on his FMS a split second after the first officer okayed the holding pattern, erasing the holding pattern from memory.

More swearing from the right seat and another manual turn from the left. Our company discouraged flying with both units in “sync mode,” but allowed the practice. In either case, we required coordination between seats whenever navigation changes are made. Another strong critique item. I was getting ready to intervene when center cancelled the holding pattern and said they could try the approach if they wished.

They wished, again violating a company rule forbidding these “look see” approaches. The critique items were stacking up.

Sure enough Vancouver was below minimums and the crew shot the approach, saw nothing, and went missed approach. Twice. Finally they asked for vectors to the alternate. Climbing through two thousand feet we were again in sunlight, and just ten miles to the west we saw the ground.

The first officer asked the captain to monitor the radios as he set them up for the approach into Abbotsford. The first officer spoke as he covered each item: the inbound course, the decision altitude, and so fourth. Center directed a descent to 2,000 feet, the captain acknowledged and set the altitude alert system to 2,000 feet, as his hand was moving from the altitude knob to the autopilot’s vertical command knob the first officer briefed the ILS frequency. The captain immediately set that in his radio and forgot to command the descent.

I counted silently to myself. At sixty seconds I would say something. The two pilots finished the approach briefing as I finished my count. “Captain,” I said, “you need a vertical mode you were cleared to a new altitude.”

Just then center asked, “Say altitude,” and the captain spotted the runway to our left. With his left hand he disengaged the autopilot, banked sharply to the left, pushed the nose over hard, and keyed the mike. “Airport in sight, going to tower.” With his right hand he reached over and extended the landing gear, the flaps, and zeroed the autopilot altitude. The first officer looked up from his approach plate and said simply, “What?”

The hapless duo landed the aircraft. During the debrief I told the captain I would be happy to sign him off for single pilot operations in the Falcon 900, provided he promise to do that only when flying for our competitor. He laughed until I shook my head and unveiled the totality of their crimes.

It was a long call to management that night. Soon thereafter the flight department left our company and the pilot pair was working for our competition. But that didn’t last long. Both pilots were fired within a few months. It seems even our competition has standards.