We all agree that aiming for the first inch of the runway is a bad idea and when we see someone else do it, we shake our heads and give a little tsk, tsk. Of course, when we do that, well that is just superior airmanship. Right?

— James Albright

Updated:

2019-05-27

I grew up aiming for what we in the Air Force back then called "brick one" but once I got to the B-747, I got that nonsense beaten out of me. There are several issues here:

1

How not to land

A recent example

I am continually amazed when I see or hear about someone aiming for the first inch of a runway. In fact, just recently . . .

This Falcon 900 was obviously aiming for the start of the runway and managed to touch down in the displaced threshold. Of course the obvious question is why?

- There is a perfectly good RNAV(GPS) with LPV and LNAV/VNAV minimums as well as PAPI — so there is no shortage of glide path information.

- The runway is 6,025' long and has 5,425' of pavement available after the threshold — so there is no shortage of runway.

Let's suppose the airplane was landing at its maximum weight (42,000 lbs), let's say it was a very hot day (100F) and that drove the pressure altitude above the field elevation (620') to a PA of 1,000'. We know they had a headwind so let's say no wind. The charts say they had a landing distance of 3,500'. Even if you add the standard 15 percent landing distance assessment, they only needed 4,025'. Now let's say they were at a normal landing weight. Distance required? Only 2,600'. Either way, this "brick one" approach was unnecessary. (And if was, KAUS is only 13 nm away and has a 12,250' runway.)

This kind of thing bends metal all the time. For an example, see: BD-700 C-GXPR.

2

Runway markings

Runway Threshold Markings

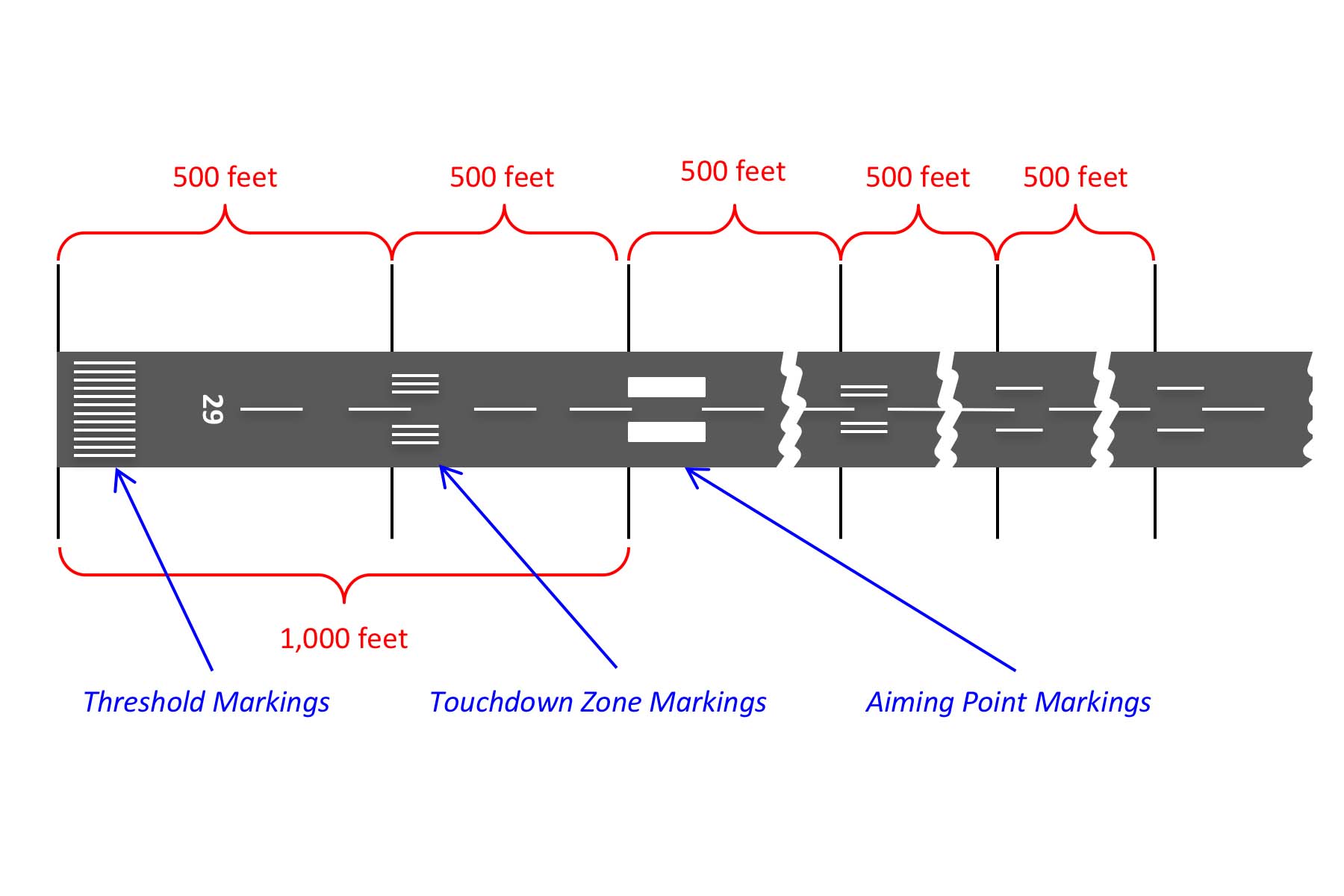

Runway threshold markings come in two configurations. They either consist of eight longitudinal stripes of uniform dimensions disposed symmetrically about the runway centerline, as shown in [the figure], or the number of stripes is related to the runway width as indicated [below]. A threshold marking helps identify the beginning of the runway that is available for landing. In some instances the landing threshold may be relocated or displaced.

Source: Aeronautical Information Manual, ¶2-3-3.h.

For narrower runways, the number of stripes can be as few as 4 for a 60 foot wide runway, or as many as 16 for a runway 200 feet or wider.

- A threshold marking shall be provided at the threshold of a paved instrument runway, and of a paved non- instrument runway where the code number is 3 or 4 and the runway is intended for use by international commercial air transport.

- The stripes of the threshold marking shall commence 6 m from the threshold.

- A runway threshold marking shall consist of a pattern of longitudinal stripes of uniform dimensions disposed symmetrically about the centre line of a runway as shown in [the figure].

Source: ICAO Annex 14, Volume I, §5.2.4

Runway Touchdown Zone Markings

The touchdown zone markings identify the touchdown zone for landing operations and are coded to provide distance information in 500 feet (150m) increments. These markings consist of groups of one, two, and three rectangular bars symmetrically arranged in pairs about the runway centerline, as shown in [the figure]. For runways having touchdown zone markings on both ends, those pairs of markings which extend to within 900 feet (270m) of the midpoint between the thresholds are eliminated.

Source: Aeronautical Information Manual, ¶2-3-3.e.

A touchdown zone marking shall be provided in the touchdown zone of a paved precision approach runway where the code number is 2, 3 or 4.

Source: ICAO Annex 14, Volume I, §5.2.6

The code numbers refer to the size of the runway, where a Code 1 runway is less than 800 meters (2,625 feet) and the higher numbers are longer.

A touchdown zone marking shall consist of pairs of rectangular markings symmetrically disposed about the runway centre line with the number of such pairs related to the landing distance available and, where the marking is to be displayed at both the approach directions of a runway, the distance between the thresholds, as follows:

| Landing distance available or the distance between thresholds |

Pair(s) of markings |

| less than 900 m | 1 |

| 900 m up to but not including 1,200 m | 2 |

| 1.200 m up to but not including 1,500 m | 3 |

| 1,500 m up to but not including 2,400 m | 4 |

| 2,400 m or more | 6 |

Runway Aim Point Markings

The aiming point marking serves as a visual aiming point for a landing aircraft. These two rectangular markings consist of a broad white stripe located on each side of the runway centerline and approximately 1,000 feet from the landing threshold, as shown in [the figure].

Source: Aeronautical Information Manual, ¶2-3-3.d.

- An aiming point marking shall be provided at each approach end of a paved instrument runway where the code number is 2, 3 or 4.

- The aiming point marking shall commence no closer to the threshold than the distance indicated [below], except that, on a runway equipped with a visual approach slope indicator system, the beginning of the marking shall be coincident with the visual approach slope origin.

- An aiming point marking shall consist of two conspicuous stripes.

Source: ICAO Annex 14, Volume I, §5.2.5

The location of the aiming point marking depends on the landing distance available. For a runway between 1,200 meters (3,947 feet) and 2,400 meters (7,874 feet) landing distance the aiming point begins at 300 meters (984 feet).

3

Look down angle

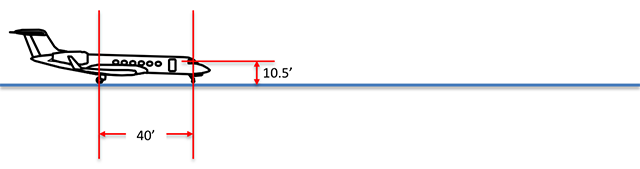

Your aim point, as your very first flight instructor told you, should be that point on the windscreen that doesn't move. That instructor would also add a lie: "If you don't do anything, that is where the airplane is going to first contact the runway." The problem with that last statement is that you have airplane underneath you, and as the type ratings accumulated, there was more and more airplane below and behind you to consider. If it were just your eyes doing the flying, then your aim point would indeed be the same as your touchdown point.

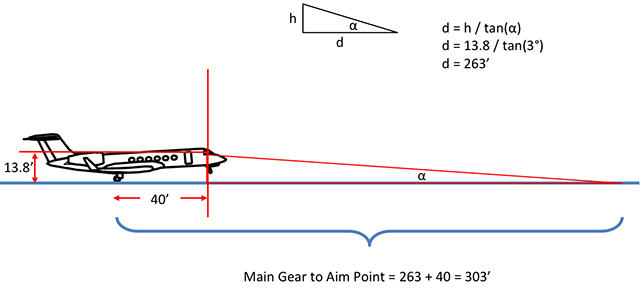

Where the airplane will touch down, then, depends on where the wheels are in relation to your eyes, the things doing the aiming. The answer varies with aircraft. We'll use the Gulfstream G450 as an example, but you can do the math for you airplane if you wish. Or you can just take away the bottom line message: don't aim for the first inch of pavement.

Look Down Angle, G450 Example

If you want to find the distance between where your eyes are pointed on approach and landing versus where your wheels are, you will need some dimensions. Specifically, you need the distance between the aft-most landing gear and the pilot's eyes. That may take some detective work or perhaps just a good tape measure.

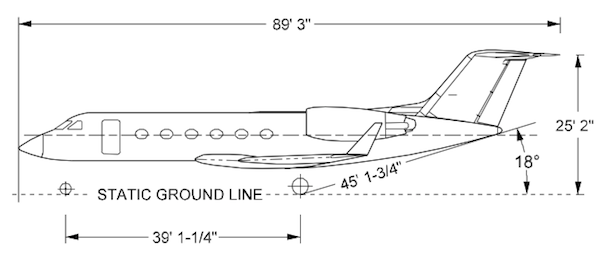

In the case of the G450, the operating manual gives us the distance between wheels: 39' 1-1/4".

The G450 Weight and Balance Manual tells us the nose wheel has a horizontal arm of 48.1" while the pilot is at 41.0", 7.1" forward of the nose gear. Assuming the pilot's eyes are at the point used for the center of the pilot's mass, we can deduce:

We'll call that an even 40 feet.

Further research leads us to a Gulfstream Eye Wheel Height Paper which tells us the pilot's eyes will be between 10.4 and 10.8 feet off the ground, depending on weight and center of gravity. We'll use 10.5 feet.

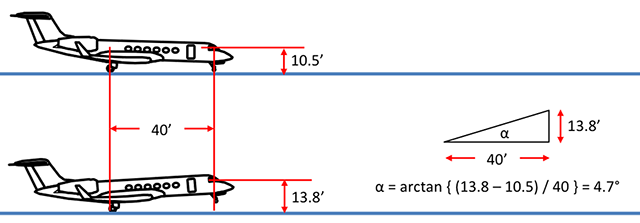

The Gulfstream Eye Wheel Height Paper tells us our eyes will be 13.8' off the runway when the wheels touch on landing, which is what we needed for this exercise. The process to find the deck angle of the aircraft is shown for the sake of further discussion below.

We can use basic trigonometry to determine the distance from our eyes to an aim point. In the case of a three degree glide path, our G450 pilot's eyes will be 263' behind the aim point, which means the wheels will be 303' behind the aim point. In other words, if you are aiming for the five hundred foot markers and don't flare, you wheels will just barely make the runway. Add a gust of wind or just a little deviation from glide path, you may not reach the runway at all.

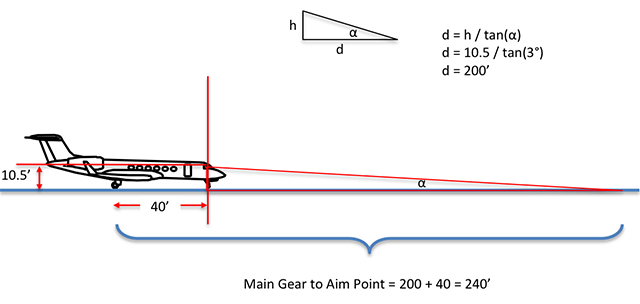

Flat Deck Angle Impact on Look Down Angle Exercise

What about aircraft with flatter deck angles? The Challenger 604, for example, has 0° approach deck angle. To isolate only the deck angle factor, we will use G450 dimensions to explore the impact of deck angle on look down angle.

As can be seen, aircraft with flatter deck angles will touchdown considerably closer to their aim points.

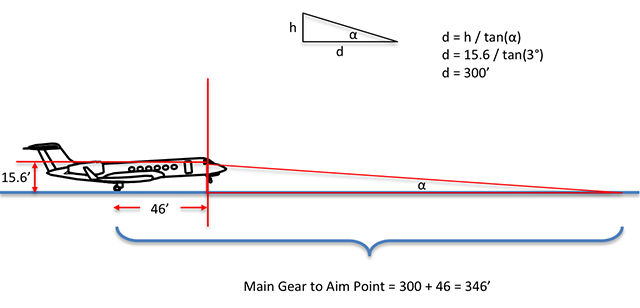

Aircraft Length Impact on Look Down Angle Exercise

What about longer aircraft? The G550 is 7'2" longer than a G450 and its wheels are 5'11" further apart. While the aircraft have the same eye wheel height when in a three-point attitude, the longer length translates to a higher pilot's eye position when the aircraft is in the landing approach attitude: 15.6' for the G550, 13.8' for the G450. This means the pilot's aim point will need to be further down the runway.

While not as dramatic an effect as the flatter deck angle, the longer aircraft does have a disproportionately longer distance to aim point. Adding a mere 7 feet to the length of the airplane increased the aim point distance by over 40 feet.

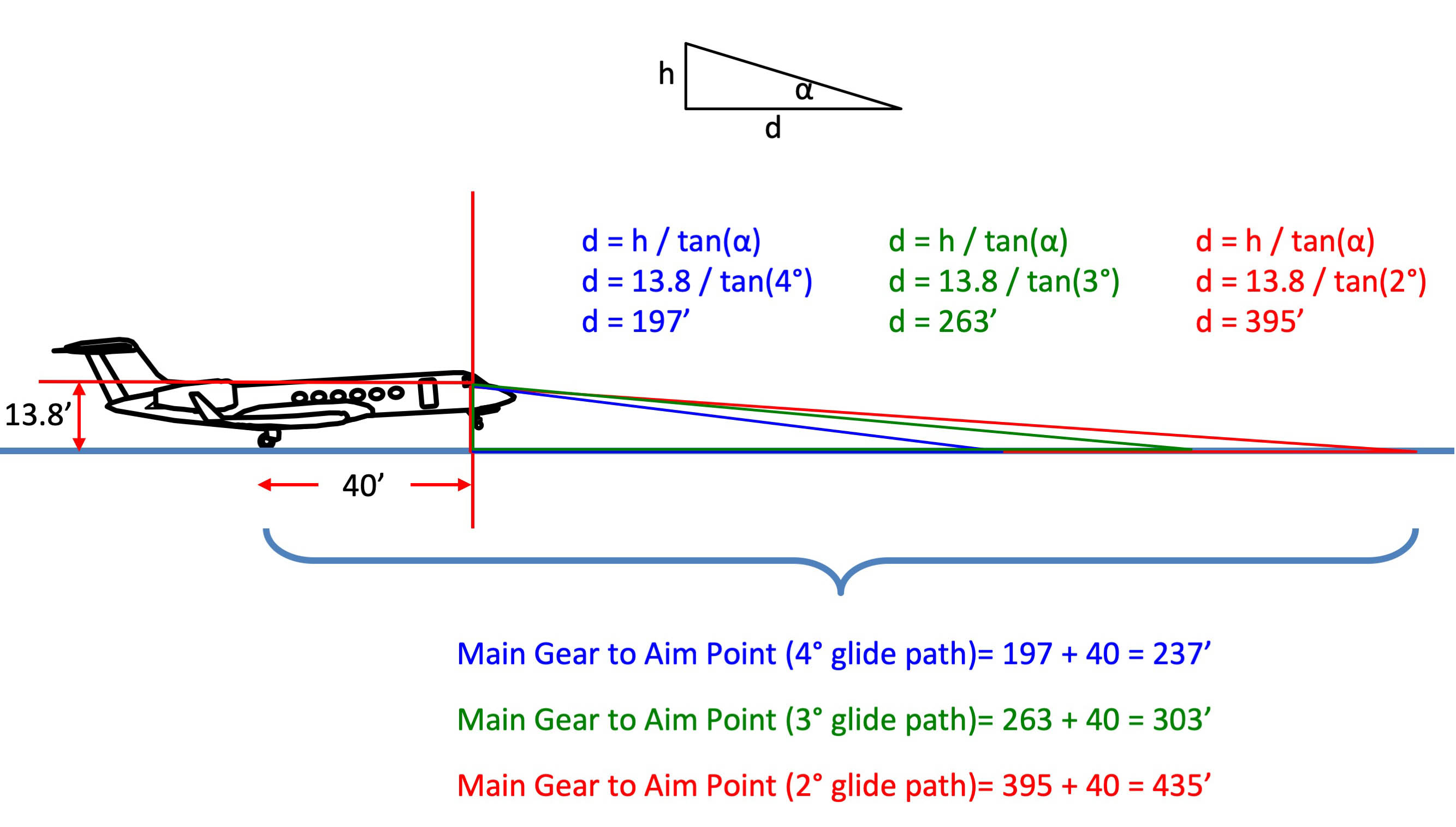

Glide Path Impact on Look Down Angle Exercise

A common tendency for inexperienced pilots is to shallow the glide path when trying to land as closely to "brick one" as possible. Experienced pilots know this is a fool's game because judging the wheel touchdown point becomes harder as the glide patch becomes shallower. As it turns out, this is proven by the math:

4

Flare distance

The round out from approach deck angle to landing flare is heavily dependent on pilot technique, to be sure. If you frequent runways short enough to require close examination of your landing distance charts, you ought to have a good idea how much runway your flare technique consumes. The Gulfstream G450 performance numbers, for example, are based on a very firm landing that you would be hard pressed to employ on a very long runway. But if you insist on those runway "grease jobs" you ought to know how to get the Airplane Flight Manual numbers when you need them. Of course I have a technique to remove the variability of my technique.

Landing distances based on 3.0° glide path at 50 feet and 6 FPS sink rate at touchdown.

Source: G450 Aircraft Operating Manual, §13-03-20

A 6 FPS sink rate at touchdown equates to 360 feet per minute. That equates to cutting your approach sink rate by less than half; it is a noticeable arrival. I've found that cutting the descent rate to 100 feet per minute gives you a soft touchdown while consuming less than an additional 400 feet. If you consciously try to avoid flaring to level flight, instead aim for that 100 feet per minute sink rate, you will be able to get close to those AFM numbers and forever avoid a floating down the runway landing.

More about this technique: Landing .

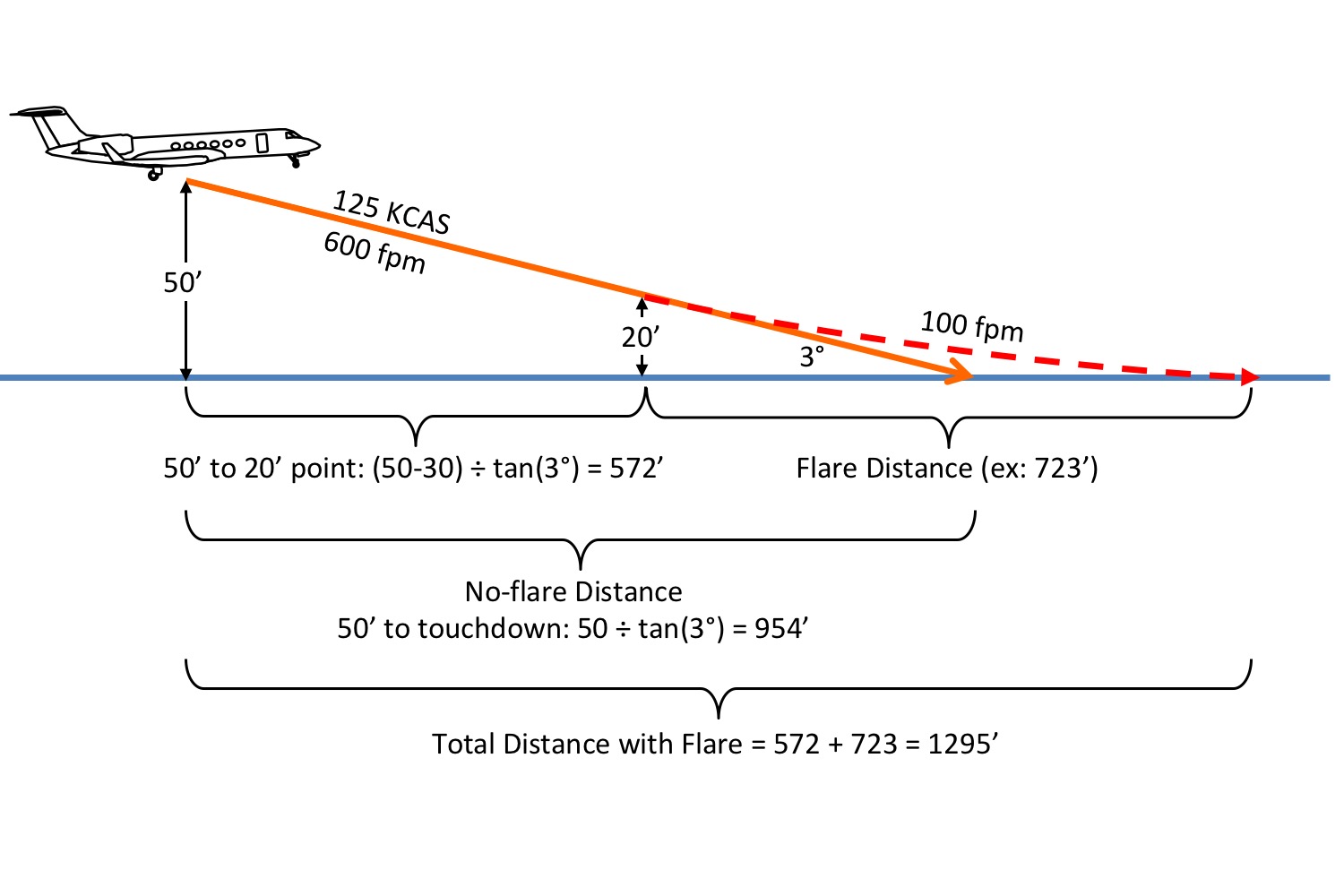

For example, a G450 flying a 3° approach at 125 KCAS will typically be sinking 600 fpm prior to initiating the flare, which should begin around 20 feet. Without a flare, the distance to touchdown from the 50 foot point can be found easily found with a little trigonometry:

If we want to start a flare at 20', which is appropriate in this airplane, we will arrive at that 20' point 572' from the threshold:

For the sake of the math, let's say we smoothly cut our descent from 600 fpm to my technique target rate of 100 fpm in a linear fashion, so that the average descent rate for the entire 20 feet comes to the average of (600 + 100) / 2 = 350 fpm:

The distance covered in 3.43 seconds at 125 KCAS:

Using this technique in the G450, we really can land the airplane within 400' of charted numbers without having the jarring 6 FPS touchdown. Since I land the airplane this way every time, I simply add 400' to AFM numbers. The only variable left for me then will be thrust reverser and wheel brake effort.

You can certainly verify your own results for whatever flare technique you use, by simply looking at the runway at touchdown, remembering to subtract the look down angle distance. Keep this distance in mind when you really need to land the airplane within the performance numbers in your manuals.

5

Letters from our readers

Dear Sir,

I enjoyed your Business & Commercial Aviation magazine article Staying on Glidepath but it brought to light something we in our flight department have been doing. We operate a Pilatus PC-12 out of [airport name redacted] and find it necessary to aim for 300' down the runway to make the 4,000 foot landing distance more comfortable. There are no obstacles on approach and we only do this "short field" technique at this airport. We follow all the rules in our manual and even add the extra 15% the FAA tells us to, just to be safe. Why do we have to use a 1,000 foot TDZ when were are considerably smaller that a Boeing 737?

Signed, R. Fader

Fort Lee, New Jersey

Mister Fader,

I notice that [airport name redacted] has a 3.00° PAPI based on a 20’ TCH. Doing the math, that intersects the runway at 381’, very close to your 300’ TDZ.

So can you do it? Yes, physically you can. But there are some more considerations.

I believe your aircraft was certified under Part 23, but maybe it is Part 25. Either way that means it was certified using a 50’ TCH. But just because it was certified that way doesn’t mean you have to fly it that way. But if you bend anything, it will be cited against you.

So what does constrain the pilot on a day-to-day basis? I believe it is the operating manual or handbook, depending on what you have. On some aircraft the manufacturer’s landing procedure will specify but on most you need to look at the performance section. So that is the first question you have to ask: does Pilatus mandate a TCH?

And that leads to the second question: just because the manufacturer defines a landing distance based on that TCH, why does the pilot have to do that? If you are operating from an uncontrolled airport without any kind of instrument approach, you might be able to argue dipping below a normal glide path is okay. If there is any kind of published glide path, you might get in trouble for going below it. 14 CFR 91.129(e)(3) says you have to maintain a glide path above a VASI. But you have a PAPI. So you could argue going below the PAPI is okay. But again, if you bend anything is is another thing for the Feds to hang around your neck.

So, bottom line: If your manuals don’t mandate a higher TCH and you stay above the PAPI, I think you are probably okay to cross the fence at 20’ and touchdown around 380 feet. If your manuals do specify something else, you need to think long and hard about deviating. But it sounds like you are putting in a lot of thought now. I recommend you document your decision making process and remember that these rules change at other airports. You shouldn’t, for example, dip below a glide slope aimed at the 1,000’ TDZ.

James

References

(Source material)

Aeronautical Information Manual

Gulfstream Eye Wheel Height Paper, GIVX-HF-06-01-11.

Gulfstream G450 Aircraft Operating Manual, Revision 35, April 30, 2013.

Gulfstream G450 Weight and Balance Manual, Revision 3, March 2008

ICAO Annex 14 - Aerodromes - Vol I - Aerodrome Design and Operations, International Standards and Recommended Practices, Annex 14 to the Convention on International Civil Aviation, Vol I, 6th edition July 2013

Please note: Gulfstream Aerospace Corporation has no affiliation or connection whatsoever with this website, and Gulfstream does not review, endorse, or approve any of the content included on the site. As a result, Gulfstream is not responsible or liable for your use of any materials or information obtained from this site.