Let's get one thing straight: I don't like to argue. If you have a different opinion than I do on a subject that has no bearing on what I am doing, will not impact me or my family, I can cheerfully listen to you espouse that view without saying anything contrary. If you ask for my opinion on something I know will provoke you, I will hold my tongue. But what if it matters? I can be persuasive, but I often fail at changing minds. Here's where you will find legions of people who think I can be a jerk. And I suppose I can be. I am trying to fix this.

— James Albright

Updated:

2022-07-15

I will provide an example where I failed in my assigned duty of intelligent persuasion, discovered a solution for the specific situation, but not a method for future events. Then, years later, I read 12 Rules for Life and found the technique I was missing.

1

Short story: a futile argument

I was a standards pilot for TAG Aviation many years ago and was often given the more technical tasks, one of which was to evaluate a vendor who promised to increase our maximum allowable takeoff weights out of many mountainous airports. Our company didn't yet have an official position on the matter and many of our operators were using the vendor. When the assignment was handed to me during a meeting of our standards group, another standards pilot volunteered to take the duty from me.

"Fine," I said. If he — let's call him Fred — had an expertise in the matter, why not? The company president said no, I would do it. I learned quickly that Fred's aircraft, a Falcon 900, often depended on the software to depart from Eagle, Colorado fully loaded with gas and passengers. If the ceiling was low, the Standard Instrument Departure (SID) climb gradients prevented him from doing that.

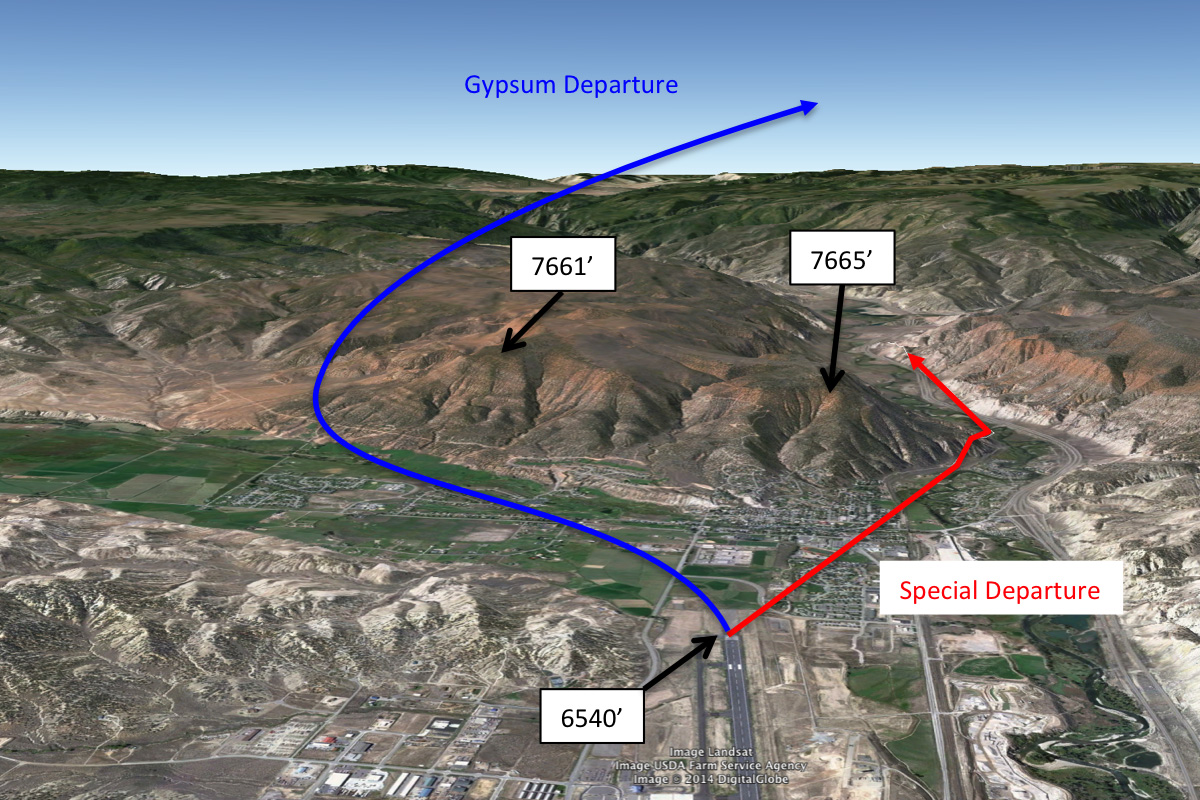

I found that the software's biggest problem was that it was using unsafe assumptions at Eagle to allow for maximum weight takeoffs. It assumed that after losing an engine at V1, pilots need only turn right to escape through a valley. The normal SID required a left turn. If you lost an engine, the software correctly assumed, you would declare an emergency and fly over the noise sensitive area without penalty. Since you declared an emergency, the SID climb gradients no longer applied. The valley to the right required much less of a climb to stay out of terra firma. All of that was true.

Note: if this all seems rather weird, see: Departure Obstacle Analysis.

The problem with the vendor's solution was what happened if you lost an engine after V1 and too late to make that right turn? Now you are committed to the left turn but you might be too heavy to make the higher climb gradient required by the mountains, and not the SID. There were other problems. If the software didn't have the necessary data on a particular airport, it defaulted to maximum weights. We also found three or four other examples were a "special departure" which deviated from the published SID could not be safely flown when the engine failure occurred at points other than at V1. So, based on all this, I recommended the software be banned. Our company instituted the ban and my fellow standards pilot, Fred, was furious.

For the next six months Fred took every opportunity to attack my inability to understand the finer points of the software. His arguments almost always started with "I've been flying from Eagle to San Francisco for years with my company and now, because of you, I can't." He mentioned that in all his years of flying he had never lost an engine. He mentioned that one of the largest fractional operators used the software for that very procedure, and certainly they had smarter experts than me. Finally, he always ended our verbal jousts with, "You position is clearly untenable."

For my part, as you might expect, I answered with math and science. You know, probability, statistics, and aircraft performance charts. At one point, after having looked up the word, I said "I have backed up my argument with facts, and therefore it is tenable."

The company held firm on my position. Because TAG had outlawed the use of the program, the software vendor investigated and addressed many of its other problems but left the Eagle Special Procedure as is. (One of their largest customers relied on it, after all.)

A year later, Fred's company sold the airplane and he found another job within TAG Aviation that didn't require the Eagle Special Procedure. He no longer cared but still threw in the word "untenable" whenever he saw me. Finally, during a dinner with mutual friends, he said, "All we needed was another ten thousand pounds!"

I thought about that for a while, looked at the problem anew and discovered the Falcon 900 could have made the necessary climb gradient using the software and the published procedures, without the special procedure. Specifically, they could have taken advantage of the software to increase their fuel load enough to make San Francisco without the risky right turn option. Since the vendor fixed the problem with defaulting to maximum weights, I came up with a solution that allowed our pilots to use the software for departure procedures that used precisely the same ground track as published SID procedures.

Fred was overjoyed at his "victory." He had, after all, won me over. I didn't contradict him in public, of course. But I had to wonder why Fred was unable to convince me when it mattered and why I was unable to determine what he really wanted during those heated "discussions." Had he made the "all we needed was another ten thousand pounds" plea at the start, I might have been inspired to look for another solution earlier. But he didn't and I failed to think outside the box when I needed to. We had both failed at the art of persuasion.

So here we are, over a decade later, and I just read something that offers a solution. Here it is.

2

Arguing by listening

Carl Rogers, one of the twentieth century's great psychotherapists, knew something about listening. He wrote, "The great majority of us cannot listen; we find ourselves compelled to evaluate, because listening is too dangerous. The first requirement is courage, and we do not always have it." He knew that listening could transform people. On that, Rogers commented, "Some of you may be feeling that you listen well to people, and that you have never seen such results. The chances are very great indeed that your listening has not been of the type I have described." He suggested that his readers conduct a short experiment when they next found themselves in a dispute: "Stop the discussion for a moment, and institute this rule: 'Each person can speak up for himself only after he has first restated the ideas and feelings of the previous speaker accurately, and to that speaker's satisfaction."' I have found this technique very useful, in my private life and in my practice. I routinely summarize· what people have said to me, and ask them if I have understood properly. Sometimes they accept my summary. Sometimes I am offered a small correction. Now and then I am wrong completely. All of that is good to know.

There are several primary advantages to this process of summary. The first advantage is that I genuinely come to understand what the person is saying. Of this, Rogers notes, "Sounds simple, doesn't it? But if you try it you will discover it is one of the most difficult things you have ever tried to do. If you really understand a person in this way, if you are willing to enter his private world and see the way life appears to him, you run the risk of being changed yourself. You might see it his way, you might find yourself influenced in your attitudes or personality. This risk of being changed is one of the most frightening prospects most of us can face." More salutary words have rarely been written.

The second advantage to the act of summary is that it aids the person in consolidation and utility of memory. Consider the following situation: A client in my practice recounts a long, meandering, emotion-laden account of a difficult period in his or her life. We summarize, back and forth. The account becomes shorter. It is now summed up, in the client's memory (and in mine) in the form we discussed. It is now a different memory, in many ways-with luck, a better memory. It is now less weighty. It has been distilled; reduced to the gist. We have extracted the moral of the story. It becomes a description of the cause and the result of what happened, formulated such that repetition of the tragedy and pain becomes less likely in the future. "This is what happened. This is why. This is what I have to do to avoid such things from now on": That's a successful memory. That's the purpose of memory. You remember the past not so that it is "accurately recorded," to say it again, but so that you are prepared for the future.

The third advantage to employing the Rogerian method is the difficulty it poses to the careless construction of straw-man arguments. When someone opposes you, it is very tempting to oversimplify, parody, or distort his or her position. This is a counterproductive game, designed both to harm the dissenter and to unjustly raise your personal status. By contrast, if you are called upon to summarize someone's position, so that the speaking person agrees with that summary, you may have to state the argument even more clearly and succinctly than the speaker has even yet managed. If you first give the devil his due, looking at his arguments from his perspective, you can (1) find the value in them, and learn something in the process, or (2) hone your positions against them (if you still believe they are wrong) and strengthen your arguments further against challenge. This will make you much stronger. Then you will no longer have to misrepresent your opponent's position (and may well have bridged at least part of the gap between the two of you). You will also be much better at withstanding your own doubts.

Sometimes it takes a long time to figure out what someone genuinely means when they are talking. This is because often they are articulating their ideas for the first time. They can't do it without wandering down blind alleys or making contradictory or even nonsensical claims. This is partly because talking (and thinking) is often more about forgetting than about remembering. To discuss an event, particularly something emotional, like a death or serious illness, is to slowly choose what to leave behind. To begin, however, much that is not necessary must be put into words. The emotion-laden speaker must recount the whole experience, in detail. Only then can the central narrative, cause and consequence, come into focus or consolidate itself. Only then can the moral of the story be derived.

Imagine that someone holds a stack of hundred-dollar bills, some of which are counterfeit. All the bills might have to be spread on a table, so that each can be seen, and any differences noted, before the genuine can be distinguished from the false. This is the sort of methodical approach you have to take when really listening to someone trying to solve a problem or communicate something important. If upon learning that some of the bills are counterfeit you too casually dismiss all of them (as you would if you were in a hurry, or otherwise unwilling to put in the effort), the person will never learn to separate wheat from chaff.

If you listen, instead, without premature judgment, people will generally tell you everything they are thinking-and with very little deceit. People will tell you the most amazing, absurd, interesting things. Very few of your conversations will be boring. (You can in fact tell whether or not you are actually listening in this manner. If the conversation is boring, you probably aren't.)

Source: Peterson, pp. 245 - 248

3

I am convinced!

In one of my jobs as the flight department manager, the company gave me a free hand at running things and things, I think, ran very smoothly. So smoothly, in fact, that I think boredom was starting to set in. Our flight operations were going smoothly and my biggest challenges seem to revolve around things other than the flight department. The hangar needed constant attention, the airport was imposing new rules, and then there were the guards. If I had any problem that really vexed me, it was the guards.

Our hangar was guarded 24/7, but only with the aircraft at home. If we were gone for more than a day, the hangar was unguarded. So the guards were paid on a per diem basis and quite often had other jobs. All of that made sense to me, because why guard a hangar that doesn't have an aircraft in it? But I suspected the guards were sleeping on duty. I often came in early in the morning and the guards seemed to have just gotten up. It was just a feeling.

Then one day I got called in to meet the CEO at company headquarters at midnight. The meeting lasted two hours. I decided to drop by the hangar at 2 am, just to say hi to the guard. I found him curled up in a sleeping bag, sound asleep. I woke him up and he got defensive. "I'm a light sleeper," he said, ignoring the fact I drove into the parking lot, opened the door, and walked right up to him with him still asleep. The next morning I started the process to fire him.

We shared the guards that the company used, about forty guards in total. The person in charge of the guards, let's call him Kyle, was incensed that I snuck up on the guard and thought I should be fired instead. The CEO called me into the office and surprised me. "We are going to fire Kyle and the entire guard force. We'll start over with a new guard force and we want you to be in charge."

I unloaded with all the reasons I couldn't do it. I don't have a background in law enforcement. (True) I don't know the rules of the profession or any knowledge of state laws and procedures. (True) I don't have training in the use of firearms. (A white lie of sorts.) I don't have the time. (Not really true.)

The CEO repeated my argument, word for word. In fact, she amplified them with more points in my favor that I hadn't thought about. And then, one by one, she asked me about ways to overcome them.

"I suppose if I had a partner who made up for my lack of pertinent experience . . ." My position was weakening. Issue by issue, I was coming up with solutions that, on reflection, I think the CEO had already thought of. In the end, I took the job.

My partner ended up being everything the company needed in a person to run a security guard company, he just didn't like the idea of being in charge of other people. We fired all the old guards, hired forty new ones, and things began to run smoothly. The CEO wanted the hangar guarded with or without the aircraft at home, reasoning that anyone wanting to plant a bomb, listening devices, or other things could do so when the hangar was unguarded. That made sense to me and it took care of the moonlighting and exhausted guard problem. My partner soon fell into the groove of actually leading people and, I think, is a natural at it.

4

I convince!

Whenever I walked around company headquarters the guards would all give me a deferential look and I overheard one say to another, "Here comes the boss." I felt uneasy about all this because my partner was doing all the work and I was, if anything, a figurehead. As each year went by I thought of ways to give up the duty, but never bold enough to confront the CEO.

Around 2018 I read Jordan Peterson's book 12 Rules for Life, and realized that our CEO was an expert in the arguing by listening technique mentioned earlier. I started using the technique with great success. My true test was about to come.

"Go buy us that newest Gulfstream."

"I can do that."

After I made my initial phone calls and started to map out the next two years of my life, I realized that time was about to become very precious. The new aircraft had yet to be certified and we would be getting one of the earliest serial numbers. That was going to mean a lot of trips to the factory and a lot of time working the completion. I was going to be pressed for time.

My next meeting with the CEO started with an update about the new aircraft and that was well received. "Anything else?" It was my chance. "I need to give up the security company."

The CEO presented me with all the reasons I had to keep the security company with an impassioned defense of points already covered, years earlier, when I accepted the job. And then, point by point, I repeated each argument. "Did I get that right?" And then I agreed with the points and concluded, "I wish I had more time but I don't. I feel my expertise is better spent worrying about the new airplane."

"Let me think about it," was the CEO's usual technique for delaying an unwanted decision and I expected as much. But I didn't expect the phone call that came the next day. "You are right, we need you to focus on the airplane. Your partner at the security company has agreed to go solo."

5

Postscript

That was about four years ago. I've since used the technique many times. Sometimes I am convinced. Sometimes I do the convincing. In either case, I have profited from the experience.

References

(Source material)

Peterson, Jordan B., 12 Rules for Life, Penguin Random House, Toronto, 2018.