A fully qualified crew skips several steps of the exterior inspection, failing to notice wooden Popsicle sticks forcing their weight on wheels system to think the aircraft is always on the ground. The crew misreads the failure of the gear to retract and skips several crew alerting system messages to use a checklist that does not apply. The crew ignores their training and either forget to disarm the ground spoiler system or later arm it for the landing. The crew decides to land without the autothrottles and chop the power at too high an altitude. The ground spoilers pop up at 57 feet and the airplane comes crashing down. The aircraft is destroyed. Bad pilots? No, they were highly qualified pilots who had grown complacent. They were lucky; they walked away. Aviation history, distant and recent, is filled with complacent pilots who did not get that chance. Complacency kills.

— James Albright

Updated:

2014-06-08

N777TY, Matt Birch (http://visualapproachimages.com/)

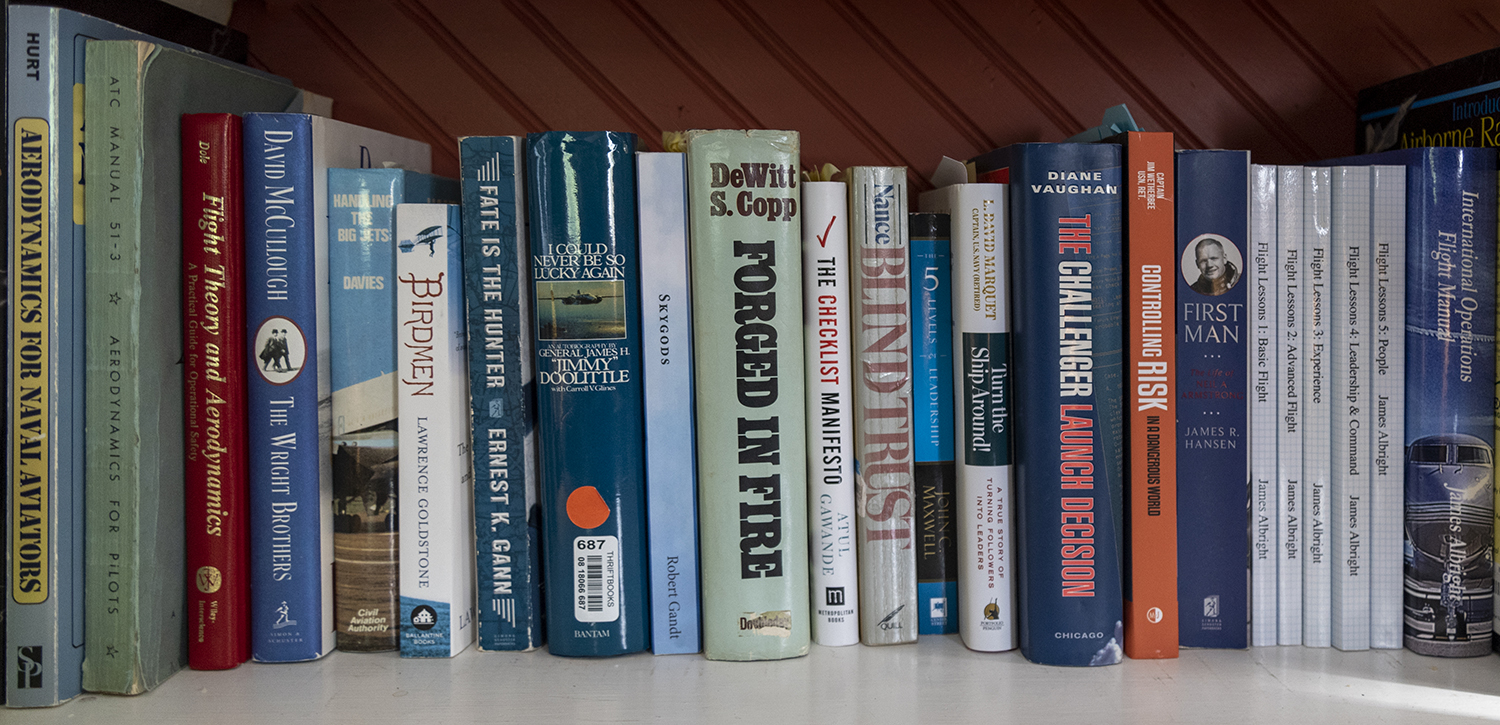

More about them: Case Study

I've heard that if you are going to have an aircraft accident, it is more likely to happen at 1,000 hours or multiples there of. I've never been able to prove that, but just because it gives me an excuse to do so, I use every 1,000 hours to reemphasize the fundamentals. One thousand hours in type? Pull out the airplane initial text books and see how much of the stuff that was important on day one is still in your head. Five thousand hours total time? Pull out the instrument manuals that gave you so much problem going for your instrument rating. Twelve thousand hours? How about pulling up every accident report ever written for your jet and see if you would have done better. Yes, it is a cheesy trick to force yourself to study. Can that be bad?

1 — Preventing complacency through scholarship

1

Preventing complacency through scholarship

First: a definition

- self-satisfaction especially when accompanied by unawareness of actual dangers or deficiencies

- an instance of usually unaware or uninformed self-satisfaction

Source: Merriam-Webster Dictionary

How Complacency Kills

While any pilot can fall victim to complacency, those in smaller flight departments outside a large standardization wing of an airline, charter operator, or management company are especially susceptible. Pilots who become comfortable with each other learn to make things go smoothly, without any drama. As things become comfortable, the hard things stop getting done. Plotting a position ten minutes after an oceanic waypoint? Why bother? Doing all full flight control check? Takes too much time! The more short cuts you take without incident, the more you are tempted to take. And it all happens without you noticing.

Even in a large flying organization complacency can go unnoticed. The top pilot in a large organization rarely gets challenged. And if that pilot fosters and rewards the behavior, pretty soon you have an entire flight department of complacent pilots.

Any pilot can fall victim to complacency, but any pilot can stop it before it kills. You simply need to stay in the books; never stop learning. You encourage your peers to keep you sharp while you do the same for them. And you lead by example, inviting critique on every flight from peers, subordinates, outside observers, and even the black boxes.

Preventing Complacency Step 1: Scholarship

As a professional pilot you can never get away from the books, you need to study to keep up with new equipment, new procedures, and new techniques. Even if none of that were to change, you need to study just to keep all that knowledge in your head.

Case Study 1.

A GIV pilot with over 17,000 hours total time was known to "unload the nose wheel on the GIV during takeoff," just like he did back in props. He wanted to make it easier on the aircraft on rough runways, ignoring the fact his jet needs a three point attitude until achieving rudder effectiveness at VMCG. All aboard his aircraft died one day in 1996 because he couldn't learn a new procedure in a new jet.

More about this: GIV N23AC.

Case Study 2.

Pilots have been succumbing to the dangers of "dive and drive" instrument approaches since the dawn of instrument flight. But by 2004 most pilots learned how to calculate a visual descent point to tame even the least precision of non-precision approaches. That year a commuter airline pilot began his descent from the minimum descent altitude a few miles early and most of his passengers died a few miles short of the runway at Kirksville Regional in Missouri. These days we have Continuous Descent Final Approaches to finally put an end to the dive and drive nonsense. And yet some pilots still insist on the old, dangerous technique.

More about this: Corporate Airlines 5966.

The solution?

Always stay in learn mode, seek out education wherever you can get it. Do not fear new technology or new techniques. Never accept "We've never done it that way" without first considering why.

2

Preventing complacency through partnership

The best tool to avoid complacency is a sharp pilot in the other seat willing to speak up, keeping you at your best. No pilot is perfect and no pilot is at his 100 percent level of performance 100 percent of the time. That's why most transport category aircraft have two pilots. If one pilot shuts the other pilot down with open hostility, dismissive comments, or even just the "cold shoulder," that pilot might as well be flying solo.

Case Study 3.

In 1999 a very senior Korean Air Boeing 747 captain made it very clear to the rest of the crew he could very well fly solo. When his attitude indicator malfunctioned he couldn't believe the other two were correct, and the first and second officers were unwilling to challenge him until it was too late. All aboard perished.

More about this: Korean Air 8509.

Case Study 4.

Even a friendly, easygoing captain can shut down a cockpit crewmember dismissively when that crewmember has the right answer. The captain on Air Florida Flight 90 made several critical mistakes on the way to the scene of the accident but his lesser-experienced first officer had deferred on each bad decision until the last. The junior pilot had an instinctual feeling the engines were not set correctly. The captain amiably dismissed these meekly offered protests and the rest is aviation history.

More about this: Air Florida 90.

The solution?

Encourage a free flow of communication on the flight deck and within the flight department.

- Good ideas should be acted upon and the proponent should be thanked. "Yes, another five thousand pounds of fuel is a great idea in this kind of weather!"

- Even those ideas worthy of consideration but not utilized can be praised. "I think extra fuel with this weather is a good idea normally, but considering the short runway at our destination and the fact we have several alternates means we should stick with the fuel we've got. But your thought process is exactly right, we should always consider adding fuel in case we have to divert around weather."

- Even bad ideas can be treated with respect. "Shemya used to be a great alternate, but they no longer have services to handle jets like ours. Are there any others?"

3

Preventing Complacency through leadership

A professional pilot invites outside critique, knowing his or her performance can withstand the scrutiny but can always be improved. A complacent pilot isn't complacent by choice, but by habit. How does a pilot know he has over time started skipping critical safety steps unless there is an outside observer willing to say so?

Case study 5.

Aircraft manufacturers often hire junior pilots without formal test pilot training as "test pilots." These pilots are surrounded by similarly-experienced pilots with very little oversight and a fertile soil for complacency. In 2000 a Challenger 604 was destroyed by a test pilot's improper, overly aggressive takeoff rotation. The NTSB found most of the company's production pilots were using the same technique, double and sometimes triple the rate specified by their flight manual. Any line Challenger 604 pilot could have spotted the problem after one takeoff, but these pilots did not have the feedback they needed.

More about this: CL-604 C-FTBZ Wichita.

Case study 6.

Even the most qualified and highly trained line pilots can fall victim to complacency. The only hull loss in the "Classic GV" series happened following maintenance. A mechanic used Popsicle sticks to place the weight on wheels system into "ground mode" while the airplane was on jacks. He forgot to remove them and the crew forgot to check them; as a result the gear did not retract after takeoff. The crew compounded their earlier preflight oversight by failing to analyze their crew alerting system messages properly, ignoring three valid checklists and opting for one that was not applicable. And then they armed the ground spoiler system against flight manual procedure. Finally, they chopped the power to idle at 57 feet; causing the spoilers to pop up and the airplane to crash down. These pilots knew better, but complacency got the better of them multiple times.

More about this: GV N777TY (West Palm Beach).

The solution?

Invite critique from your peers, from outside sources, and from technology. Perfection is unobtainable, of course, but improvement is always within our grasp.

- Critique your own performance publicly, but positively. "I ended up a little tight on downwind, perhaps I should have allowed more drift for the wind." Offer critiques of others in the same positive light. "I guess the winds at pattern altitude were not the same as tower winds, perhaps we could have increased our drift angle."

- Getting a check ride in the simulator might be a good start but having an outsider with a red pen and a pad of paper in the jump seat while you are flying your passengers is quite a different experience. Even if you aren't flying a 14 CFR 121 or 135 operation where such things are required, you should find an opportunity to do this. Invite an outside review from a Safety Management System vendor or even a fellow pilot from the next hangar down. Having a third set of eyes watching you can illuminate something wrong that you may have grown accustomed to.

- Install a Flight Operations Quality Assurance (FOQA) system. FOQA takes the same inputs used by your flight data recorder and reports back when things aren't right. If your approach isn't stable or your landings are a bit long, FOQA will see it and will let you know it. Don't look at each report as an opportunity to mete out punishment, but a chance to offer course corrections. Even to yourself.