Though I've never landed at the wrong airport, I know a few pilots who have or who have come pretty close. But these were in the days before GPS.

— James Albright

Updated:

2020-01-25

I used to think I had a special advantage because I've almost always been assigned to organizations that required their pilots to operate IFR, "to the maximum extent possible." But in the first two stories we see the Air Force was in no way immune to this kind of thing. In the third, we see a squadron mate of mine from the 89th Airlift Wing at Andrews did once land at the wrong airport, but he was in a very unusual circumstance. (See Too Many Secrets, below.) The stories that follow are ones I've collected since then that I think have a lesson to teach.

The truth is that it is easy to make this mistake when you are flying a very fast airplane with very small windows and are being pressured to do things very quickly. Looking at a few examples, however, can show you how easy it is to get this wrong. Moreover, thinking about it ahead of time can give you the techniques needed to avoid the same mistakes.

These stories are given chronologically and the lessons learned immediately following.

1986: Air Force Boeing 747 (E-4B) — The too early visual call

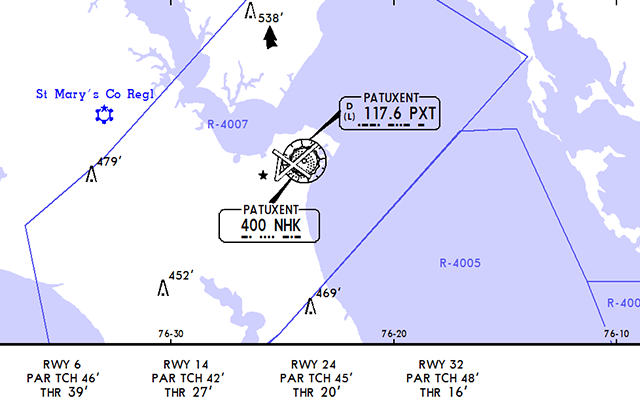

A few months before I showed up for duty at my Boeing 747 squadron they had a trip that required they overfly the runway at Patuxent Naval Air Station prior to landing. This was a visual maneuver and the cockpit was packed with an instructor pilot in the right seat, a fully qualified pilot in the left seat, and a brand new (and still not fully qualified) pilot in the jump seat.

The instructor called "visual" fifteen miles out and set up for the approach to Runway 14 at Patuxent. That wasn't the longest available runway, but it was plenty long, just over 9,700 feet. This wasn't the first time for either of the qualified pilots at Patuxent and once the right seat pilot called visual the rest of the crew got ready for the fly over and eventual landing. Everything seemed to go well until they overflew St Mary's County Regional (2WG) airport's 4,150' runway. The pilot flying was not concerned and was getting ready to turn downwind. The pilot in the jump seat felt something was wrong but kept silent until he spotted the Patuxent River NAS, still ten miles east. "Runway straight ahead!"

A View of St Mary's County Regional (2WG), Maryland, not Patuxent River NAS (KNHK), from GoogleEarth

Nobody at the small regional airport seemed to notice a Boeing 747 flying over their runway at 1,500 feet and the passengers waiting at Pax River were none the wiser. The pilots kept the incident to themselves until, years later, the jump seat pilot told the story. Right about then, our approach plates started to add geographic features . . .

When I got qualified I started carrying terrain charts for every airport we went and that definitely helped. But bringing this lesson forward to today, it definitely helps to visualize the airport in the context of the surrounding water. You might even add that to your approach briefing if you will be flying a visual or circling approach. For example, "We are looking for Pax River which sits on a peninsula surrounded by Patuxent River to the northwest and the Chesapeake to the east."

Lesson Learned: Brief the geography on a visual approach

When flying a visual approach make an effort to find sources of geographic clues. These can be terrain charts, a sectional, or even a color coded approach plate. But however you find the information, include it in your briefing. In our previous example we had the advantage of water. But we can brief geography even at land locked airports. Examples:

- "We are flying a visual approach to Las Vegas International Airport. There are two north-south runways and two east-west that form the letter "L" when viewed north up. The airport is west of the city."

- "There is a chance we will be given a visual approach to Runway 22L at Chicago Midway. Runways 22L and 22R and Runways 31C and 31R criss-cross each other to form a 'double x' on top of a square of land in the middle of city. The criss-cross is as at angle to the street lines so we need to be careful not to angle our downwind or base using the streets for alignment."

1990: SR-71 — The problem with speed

I have a friend who was flying the SR-71 at this time and he never heard of this incident. When guys at the top of the pilot food chain screw up, the food chain itself closes in to hide the error. But that was in the days before cell phones and millions of amateur photographers ready to capture these mistakes for all to see.

I was flying a Boeing 747 for the Offutt Air Force Base air show in 1989 (as I recall) and after our demonstration we left the pattern to get some training done elsewhere. While we were gone we heard and SR-71 for a high speed pass over Millard Airport, about 10 nm to the west of Offutt. Both airports have a Runway 12/30 but that's where the similarities end. Millard has a 3,801' runway, Offutt's is 11,703' long. Millard is a small airport with a few buildings nearby. Offutt, at this time, was home to the Strategic Air Command.

How could this happen? Just imagine looking out the very small windows of the SR-71 while looking for that small piece of asphalt? Now how big are your windows? It's a good thing you have GPS and all those other electronics to help your situational awareness. But all those electronic gizmos do you no good at all if you aren't using them.

Lesson Learned: Don't assume basic skills continue to be basic in "non basic" aircraft

We pilots have a tendency to think our skills do nothing but grow, accumulating from one airplane to the next and year after year. But this ignores the fact that (a) each airplane imposes different restrictions to the tasks, and (b) we lose skills without practice. Looking outside the very large windscreen of a Cessna 152 while traveling at 70 knots makes the task of airport identification quite easy after a few hours of instruction. Now let's decrease that window to the size found on a typical business jet and jack up the speed to 250 knots. It isn't so easy now, is it?

So it is more difficult, we get that. What's the lesson? Simply put, don't be so quick to accept a visual at an airport you've never seen before. Even if you have a history with the airport, realize the odds are stacked against you and perhaps using technology to even the odds is a good idea.

1996: Too Many Secrets — Atlas Air — Pilot controlled lighting at the wrong airport

Nobody wants to talk about a wrong airport landing and these things tend to get hushed up rather quickly. You aren't going to find much about this incident because the cargo was classified and it happened in a very secluded area. I know the pilot who made the landing. Immediately following the incident he was fired. But Atlas Air investigated and determined he was not at fault, so he was rehired. That speaks volumes about Atlas Air.

Pinal Airpark (MZJ) sits about 30 miles north of Tucson, Arizona and is known as one of the world's largest aircraft bone yards. It has been home to hundreds of Boeing and Airbus aircraft since the 1990's. Another thing it used to be home to is a lot of secret government cloak and dagger activities that required secret stuff transportation late at night. And that is where Atlas Air comes in.

I am told that in the early 1990's this involved waiting until complete darkness, flying a Boeing 747 at about 5,000' and along the 320° radial off the TUS VOR for about 15 miles until you fly over what are known as the "Picture Rocks" which rise to about 3,300' MSL. At that point you descend to 3,000' and look for the Pinal Airpark about 12 miles ahead. You will lose the VOR signal so this is pretty much done with dead reckoning. Since this is always done at night, your next step is to activate what was, back then, a secret set of pilot controlled runway lights.

My friend had flown this maneuver many times so what was once strange and scary became familiar and routine: 5,000' on the radial, 15 DME descend to 3,000', five clicks on the secret frequency, there's the runway, land. Easy.

He had no idea there was another airport, just five miles north of the mountains, called the Avra Valley Airport (AVW). More importantly the Avra Valley Airport had no idea the airport to their north had installed pilot controlled lighting because that airport was (at the time) a secret. So Avra Valley installed their own set of pilot controlled lighting and I am sure you have figured out by now, they chose the same frequency.

So the next time my pilot did the pass the rocks, descend, five clicks routine he was surprised to see the airport appear sooner than he was used to. No matter, he steepened his glide path and landed. The runway he thought he landed on was 6,849' long by 150' wide. The runway he did land on was 6,901' long by 100' wide. The next day he was fired. Atlas didn't want any other pilots making the same mistake and discovered what really happened. They unfired the pilot. Happy ending and we all learned something . . .

Lesson Learned: A visual approach at night is rarely a good idea

Things are rarely as easy at night as they are during the day. When I was in Air Force pilot training we had two crashes at night blamed on visual illusions and that resulted in a new regulation that said that if some kind of electronic or visual vertical guidance is available, it must be used.

That is pretty sound advice. With all things equal and you have a choice of runways, pick one with an ILS, VASI, or PAPI. These days you can also rely on a good RNAV with LPV. Some aircraft will allow you to draw an electronic guidance from the aircraft to any landing surface. But you have to be proficient with the gizmos to use them effectively.

Lesson Learned: Just because it worked before, doesn't mean it will work again

As my friend at Atlas Air found out, a familiar setting can become unfamiliar without warning. In this case the intended airport didn't change, the surrounding environment did. Here again, having an electronic back up can save the day.

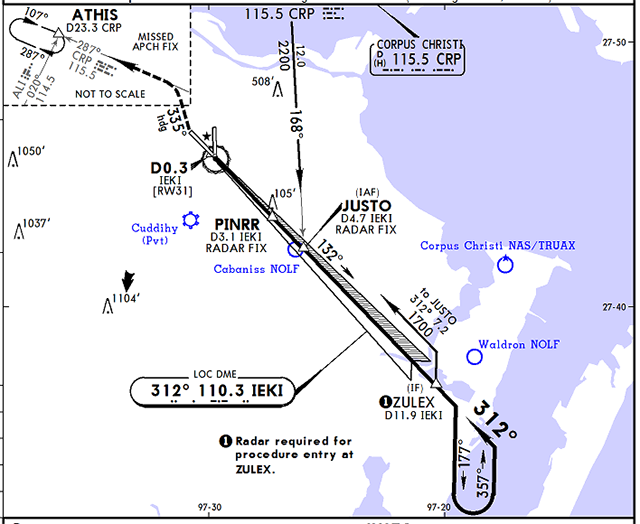

1997: Continental Airlines N16618 — The unmonitored approach

This was a fairly high tech Boeing 737 for the time but it did not apparently automatically listen to the localizer signal to interpret the Morse Code, which the pilots also failed to do. They tuned in the proper frequency (110.3 IEKI) for the Localizer Runway 31 into Corpus Christi but did not check the identifier by listening for the Morse code. They didn't know the controller had recently selected the opposite runway's localizer (110.3 ICRP) and that the localizer to Runway 31 was inactive. Along their final approach path, the pilots spotted Cabaniss Field Naval Outlying Field (KNGW), which also has a Runway 31. They assumed it was the correct Runway 31 and landed. They were wrong.

Some aircraft will automatically listen to the Morse Code for you. But you still have to look for the ident and you cannot assume typing the identifier guarantees only the correct ILS will be tuned. More about this under the lessons learned.

- The flight was issued vectors to intercept the final approach course of Runway 31 at Corpus Christi International Airport, and was cleared for the localizer 31 approach. The first officer was manipulating the controls, the In-Range and Approach checklists were completed, and the approach was briefed. A previous aircraft had requested the ILS RWY 13 approach and the tower controller had switched the ILS localizer from 31 to 13. After the completion of the approach, the tower controller did not reselect the localizer 31 approach.

- Descent into Corpus Christi was initiated. The In-Range checklist was completed passing through about 18,000 feet. The flight crew briefed on the approach they would be using into CRP and "specifically mentioned about crossing the Ducky [final approach] fix at 1,600 feet, but based on the ATIS information, we anticipated picking up the field visually to proceed on in for the landing." At about 13,000 feet they contacted Corpus Christi Approach and they were instructed to turn to a heading of 195 degrees and to continue their descent. At this point the Captain showed the First Officer how to build the approach using the FMC. He then showed the First Officer "how to use the intercept course function on the legs page of the FMC CDU (control display unit) by bringing Ducky into the active waypoint (1L) and then selecting intercept course (6R) and executing the function. This built the final approach course from Ducky on out to the southeast." The flight crew did not properly identify the localizer for Runway 31 via the audio Morse code signal.

- After descending to 2,000 feet the aircraft was in and out of a broken cloud layer which "somewhat" obscured the flight crew's view of the surrounding area. The visibility was about 5 to 6 miles. Approach control instructed the flight to turn to a heading of 280 degrees and cleared them for the Localizer 31 approach into CRP. The Approach checklist was then completed. The Captain did a double check of the NAV AID set up to make sure they had the proper configuration for the approach. He noticed the First Officer had not armed the VOR mode of the Mode Control Panel so he pointed out this fact and armed it for him. They were about 2.5 miles right of the computed course at that time, still in and out of the clouds. The flight intercepted the localizer for Runway 31, "although at the very beginning the course deviation bar did a couple of full scale deflections as if when something interfered with the localizer but it settled down right away and we locked on and tracking it inbound about 7 miles southeast of Ducky," the final approach fix. After verifying all of the instruments were properly configured for the approach, the Captain looked outside and "saw a runway at the northern edge of the cloud they were in and out of." He then said, "runway in sight, let's land." The runway also had the number 31 painted on its approach end. The First Officer asked the Captain if they "could make the landing from here and the Captain said yes." The autopilot was disconnected and they started a visual descent to the runway. The Captain reported the airport in sight to approach control, and he was instructed to contact tower control. Tower control cleared the flight to land, and subsequently the aircraft made an uneventful landing on Runway 31 at Cabaniss Field.

- The National Transportation Safety Board determines the probable cause(s) of this incident as follows: The flightcrew's inadequate in-flight planning and decision, and their failure to refer to the navaids needed for the instrument approach procedure. A factor was the lack of a minimum safe altitude warning from approach control.

Source: NTSB Accident Docket FTW97IA187

The localizer transmitter operates on one of 40 ILS channels within the frequency range of 108.10 to 111.95 MHz. Signals provide the pilot with course guidance to the runway centerline.

Source: AIM, §1-1-19, ¶b.1.

Lesson Learned: Tune, identify, and monitor

Just because the needles react as you expect them to does not mean they are telling the truth. Your very first instrument instructor emphasized TIM (Tune, Identify, Monitor) and the still holds true today.

There are only 40 localizer frequencies and the chances that another nearby airport is using the same frequency is higher than you might think. You need to identify the Morse Code. Some aircraft will do this for you but you need to understand how reliably it does this and what its limitations are. Gulfstream and FlightSafety once taught that entering the ILS identifier instead of the frequency guarantees only the selected ILS would be tuned and this was the company line for over ten years. (I think there are still proponents of this view.) I was able to demonstrate that this does nothing other than dial in the desired frequency and you could very well end up with the wrong ILS:

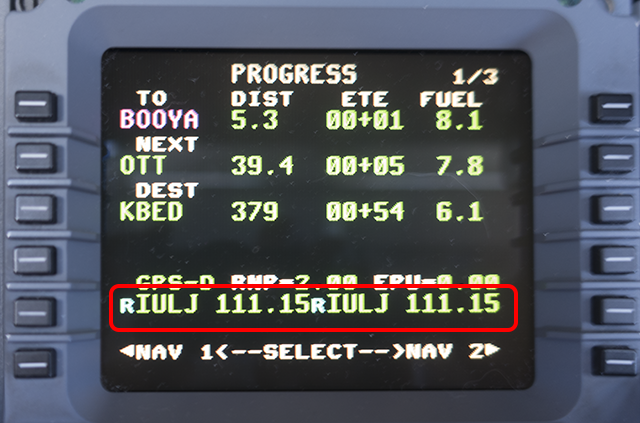

Before we learned better, we would type in IULJ into the FMS and once we saw it had tuned 111.15 for KBED and thought we were done. But if we did this early enough when flying in from the south, the IULJ would turn to IGFN which is the localizer to Runway 32 at Greensboro, or ITKD which is the localizer to Runway 22 at LaGuardia. Listening to the Morse Code verified this. We've also seen localizers for Memphis, Orlando, Indianapolis, and so on. All 111.15.

Entering the "IULJ" ILS ident for KBED in the G450 FMS PROG Page

FlightSafety taught for ten years that this is just as good as monitoring and guaranteed the correct ILS.

We sent photos of this to Honeywell, who grudgingly acknowledged this to be true: typing in the identifier does not guarantee only that localizer will be tuned, only that the matching frequency will be tuned.

Seeing "IGFN" on the PFD after entering "IULJ" in the MCDU

So the only thing you can be sure of is that 111.15 is tuned.

Honeywell continues to say that once the needle comes up and you do indeed see the letters on the Pilots Flight Display (PFD) that the avionics have listened to the Morse Code and you are good to go.

Since they were wrong the first time I have continued to be skeptical. But after watching this for few years it appears to be true for our Gulfstream PlaneView cockpit. Seeing the letters on the FMS tells you only that the frequency is tuned, but once you see the letters on the PFD you can trust they are being monitored.

Seeing "IULJ" on the top of the PFD once on raw data.

Honeywell says the machine has listened to the Morse Code for us.

Lesson Learned: Use all available tools all the way through landing

In many of these wrong landing examples the mistake could have been caught had the pilots continued to use their instruments after saying the word "visual." You should also be cross checking these needles to ensure you are flying a stable approach, after all.

2004: Northwest Airlines A319 — Heading for the biggest piece of concrete

When you are going to a remote city and the destination is an airport that bears the name of the city, you might be inclined to think that airport is the largest in within sight of the city. This is often untrue.

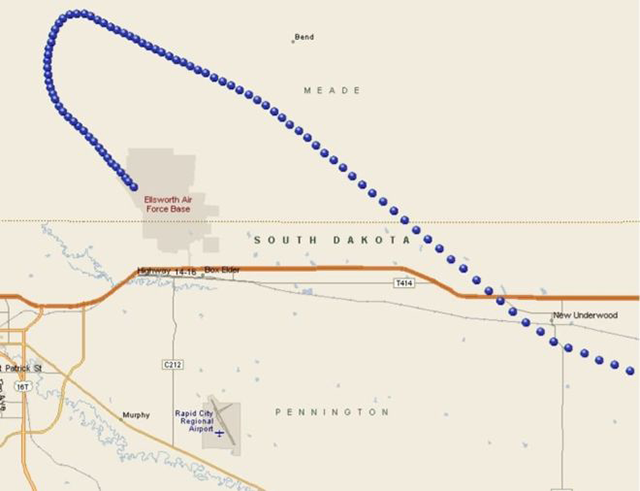

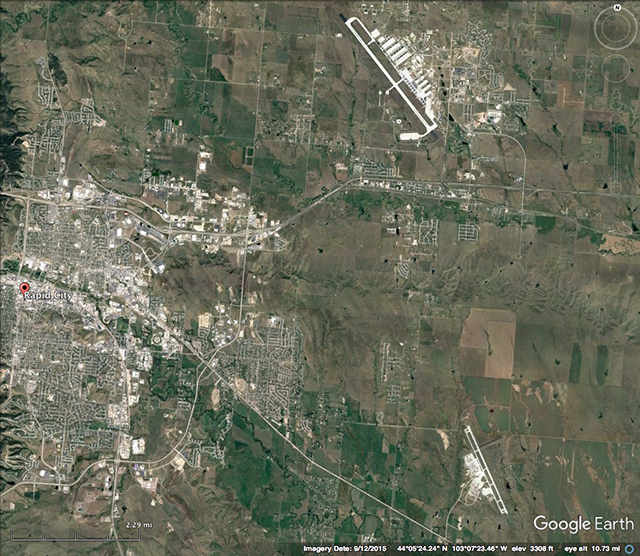

Can you guess which airport is civilian and which is military? Hint: the Air Force has a very large presence here.

A Northwest Airlines flight that was headed to Rapid City, S.D., landed a few miles off course at Ellsworth Air Force Base, and passengers had to wait in the plane for more than three hours while their crew was interrogated.

Passengers on Northwest Fight 1152, and Airbus A-318 from St. Paul, expected to be welcomed to Rapid City Regional Airport on Saturday, but after about five minutes they were told to close their window shades and not look out, said passenger Robert Morrell.

"He [the pilot] hemmed and hawed and he said, 'We have landed at an Air Force base a few miles from the Rapid City airport and now we are going to get from here to there,' Morrell told the St. Paul Pioneer Press by cell phone during the delay Saturday.

Eventually, the captain and first officer were replaced by a different Northwest crew for the short hop to the right airport.

Source: The Free Lance Star, June 21, 2004, Airliner arrives on time, but at wrong airport

Lesson Learned: Understand the local airport landscape

In many cities there are several airports jammed into the same general area. Since they probably were built to consider the same prevailing wind conditions, they often have runways with the same general direction. Also beware of cities where an older military field that has since closed still provides the most tempting landing surface. Tempting, but wrong.

2013: Atlas (Again?) — If you think you are too high to land, you probably are

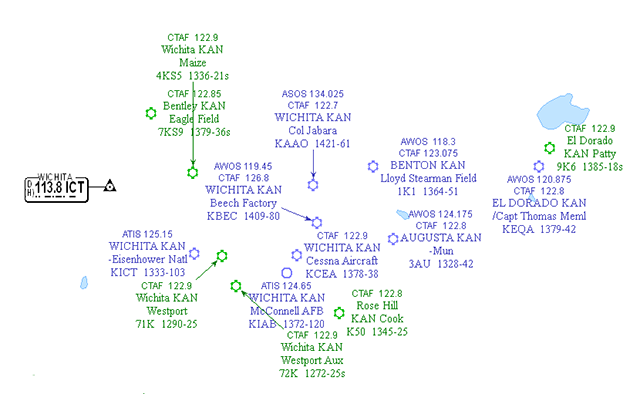

Wichita is what we in the Air Force would call a "target rich environment." When you are behind enemy lines in charge of shooting something, anything, that is a good thing. When you are tooling around at night looking for the correct airport? Not so much.

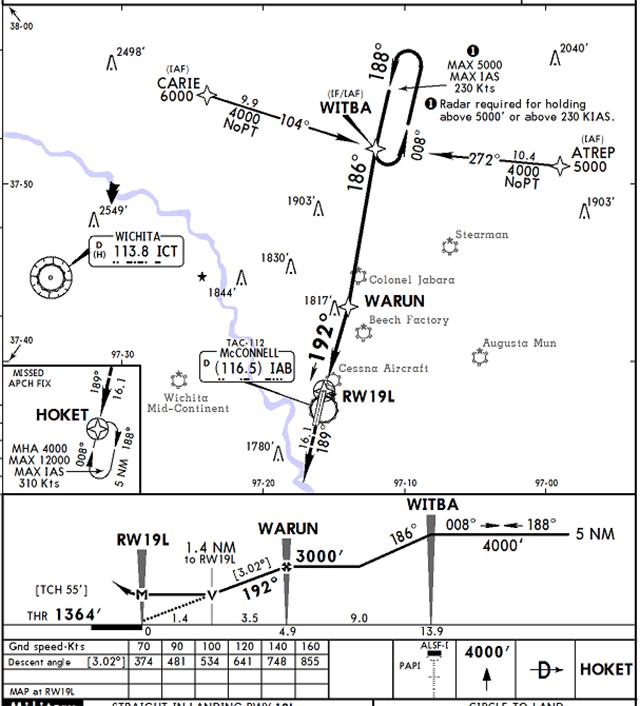

On November 20, 2013, a Boeing 747 Dreamlifter (N780BA) operated by Atlas Air inadvertently landed at Colonel James Jabara Airport, a small general aviation airport in Wichita, Kansas. Its intended destination was McConnell Air Force Base, 9 miles past Jabara Airport on the same heading.

Atlas Air’s internal investigation into how its crew landed a Boeing 747 Dreamlifter at the wrong airport last November has uncovered important factors explaining how the freighter, headed to Wichita’s McConnell Air Force Base, mistakenly landed at the smaller Jabara Airport, nine miles to the northeast of the air base.

In a crew-training video obtained by AIN, Atlas Air flight operations vice president Jeff Carlson said that a number of intermittent issues with the first officer’s primary flight display earlier in the night-time flight created some skepticism on the part of the pilots about the reliability of the aircraft’s automation system. Although Wichita’s weather was good, the pilot flying programmed an Rnav/GPS approach to Runway 19L at McConnell that would have placed the aircraft at 3,000 feet over Jabara. According to Carlson, the pilot said previous VFR approaches to McConnell had often put him at a higher altitude than expected and that difficulties in picking out McConnell’s runway prompted him to make an instrument approach.

The two pilots did not brief each other about other area airports or the 19L approach lighting system that could have helped them to verify that they were landing at McConnell. Wichita approach controllers cleared the 747 for the instrument procedure 25 miles out and immediately switched the aircraft to the McConnell tower, which cleared the aircraft to land. The 747 remained on autopilot until passing the initial approach fix, at which time the flying pilot saw a brightly lit runway slightly to his left, which seemed to match what he was searching for.

Believing the aircraft was too high to land safely, the flying pilot disconnected the autopilot and increased the rate of descent toward what he thought was 19L at McConnell but was in fact Runway 18 at Jabara. The pilot monitoring was uncertain about the runway’s identity, but remained silent.

Carlson said the primary reason for the incident was the flying pilot’s late decision to abandon the instrument approach for a visual approach that required him to hand-fly the aircraft, as well as inadequate monitoring by the other pilot. Also mentioned in the video, which Atlas has not released for public viewing, was ATC’s failure to notice the aircraft descending toward the wrong airport.

Atlas Air now requires pilots to remain on an instrument approach procedure–even in visual conditions–until passing the final approach fix.

Source: Mark

Lesson Learned: Use the instruments to aim the airplane vertically as well as horizontally

There are two unusual statements from Atlas about this incident. First, the pilot thought the RNAV/GPS was bringing him in too high but decided he was abeam the intended airport before crossing the final approach fix. Second, the company's solution to require staying on instruments until the final approach fix still leaves lots of room for this kind of mistake. If you want to prevent falling into the same trap that got these two pilots, I recommend the following:

- Use all available information on the approach plate to remain situationally aware. You can use DME, waypoints, and even crossing radials to understand when a descent should be started. If you spot a runway that isn't straight in front of you and the distance you expect, chances are you've spotted the wrong runway.

- If you have vertical guidance from the cockpit (a glide slope needle, a VPATH indication, or even a synthetically derived vertical path), stay on it until you have vertical guidance from the runway (VASI, PAPI, etc.). If the ground indications differ significantly from the cockpit indications, ask for help. "Tower we have an avionics issue here, can you confirm you see us on about a five mile final for Runway 19 Left?" It sounds weird and may earn you some ribbing at the bar, but it could save you your job.

2016: D.E.L.T.A. Airlines — "Don't Ever Land There Again" lesson ignored

I've heard from more than one airline pilot that when they get a chance to fly a visual approach, they pounce on it. The chance to fly their aircraft without reference to approach needles and other instruments, "It really helps you to keep sharp!"

This crew appears to have been professional in most regards but fell into a trap of being too eager to go from instruments to visual, and too willing to bend their stable approach rules rather than go around. At 500 feet above the wrong runway the aircraft was doing 1,200 fpm and the pilots should have gone around. Had they done so, they would have noticed the bombers parked on the ramp and we wouldn't be using them as an example here.

- The flight was routine until nearing the Rapid City terminal area. The crew had initially briefed for landing on runway 32, but the wind had shifted and favored runway 14. The crew reported that they had prepared for the runway 14 approach as well, so the change was not a significant factor. Delta chart material did include an advisory regarding the close proximity and alignment of the two airports.

- Landing on runway 14 required more flying distance than runway 32, however, at 2030, the crew discussed the need to descend more rapidly. The flight was not altitude restricted by ATC.

- At 2035, ATC instructed the flight to fly heading of 300 degrees for the downwind leg of the visual approach. At that time the airplane was 9 miles abeam RAP at 12,000 feet. The ATC controllers noted that the airplane was high and fast for the visual approach. Field elevation of RAP was 3,200 feet and with a nominal remaining flying distance of about 15 to 18 miles the airplane was positioned well above the typical 300 feet per mile descent.

- At 2036:30 the captain called the airport in sight and called for gear down and flaps one, configuring the airplane for a more expeditious descent. At this point RAP was southsouthwest of the airplane, at the 8 o'clock position, while RCA was at the 10 o'clock position, therefore, it is likely the captain was actually looking at RCA.

- Shortly afterward, ATC issued a vector for base leg, but the crew requested to extend the downwind due to high altitude, which ATC approved.

- At 2039, the crew accepted a turn to base leg as the airplane was descending through 5,800 feet, about 5.5 miles north of RCA, and about 12 miles north of RAP. This was consistent with altitudes on the RNAV14 approach to RAP, but a somewhat steeper than normal angle to RCA.

- ATC cleared the flight for "visual approach runway one-four. Use caution for Ellsworth Air Force Base located six miles northwest of Rapid City Regional." FAA order 7110.65 directs controllers to describe the location of a potentially confusing airport in terms of direction/distance from the aircraft. During interviews, the crew stated they misheard the controller's warning for the typical position advisory given on an instrument approach, and it supported their idea that the correct landing runway was 6 miles away. The FO did query the Captain if he had the right airport in sight, who expressed some uncertainty. Both crewmembers had little to no experience flying into either RAP or RCA, however, they did not verify their position to the desired landing runway using either the automation, or by querying ATC; and switched off the autopilot and Flight Directors removing possible cues as to their position related to RAP.

- At the time ATC cleared the flight for the visual approach the airplane was positioned on the final approach course of the RNAV14 approach, and at a reasonable altitude for that approach, therefore, there was no immediate indication to ATC that the crew had identified the wrong airport.

- The captain reported that about 500 feet agl he did not observe the PAPI lights; however, he remained "focused on the visual approach." At 2041:25 the captain stated "confirmed stable." The airplane was 1.5 nm from the threshold of KRCA, 8 nm from KRAP. The airplane was descending approximately 1,200 feet per minute, and the captain said "this is the most [expletive] approach I've made in a while."

- As they approached the runway, the captain retarded the thrust levers to idle, at which point they realized that they were landing at RCA. According to both crewmembers. the landing runway 13 was "uneventful" and they cleared the runway onto taxiway "D" and notified the RAP air traffic control tower.

Source: NTSB DCA16IA200

Lessons Learned: If the approach isn't stable, there could be a good reason

If you are in the habit of doing everything the right way and then, for some inexplicable reason, the approach doesn't work out the way you expected, chances are you've made a dumb mistake somewhere along the line. While I am not a fan of going to a holding pattern to sort things out, sometimes you have to do just that.

It Keeps Happening

I have to admit that I am dumbfounded about how this keeps happening. Back in the pre-GPS days we had some excuses. Weak excuses, but excuses nonetheless. But if you have a GPS you have a way of backing up the visual that is fool proof. Except fools can be fooled.

Flight track of American Airlines Flight 862, Page Field (FMY) versus Fort Myers (RSW), August 30, 2018

American Airlines Flight 862

The weather was good and the crew of this Airbus A320 was cleared for a visual approach to Runway 06 at KRSW. Instead, they lined up on Runway 05 at nearby Page Field, a general aviation airport. They got down to 875 feet before ATC noticed and directed them to break off the approach. According to a passenger: “Once we got close, he [the pilot] said we were going to be landing soon but then we started to drop really fast and I felt we were on a carnival ride. My stomach was turning. I was feeling really sick”.

References

(Source material)

Aeronautical Information Manual

Daily Mail Reporter, Dreamlifter pilot who landed at wrong airport 'couldn't read his handwriting' and got confused between east and west,, 22 November 2013

Lowy, Joan, Delta Airlines flight lands at Ellsworth Air Force Base by mistake, Air Force Times, July 8, 2016

Mark, Robert P., Atlas Identifies Causes of 747's Landing at Wrong Airport, AINonline, January 6, 2014

NTSB Aviation Incident Final Report, Airbus A320 211, Runway Incursion, N333NW, 07/07/2016, DCA16IA200

NTSB Accident Docket FTW97IA187, Boeing 737-524, registration: N16618, CONTINENTAL AIRLINES, INC., May 11, 1997 in CORPUS CHRISTI, TX, 05/04/1998