This accident is more about HAZMAT than pilot procedure; it offers a sobering reason for pilots to be more leery about the cargo and even the carry ons placed in their charge.

— James Albright

Updated:

2018-05-01

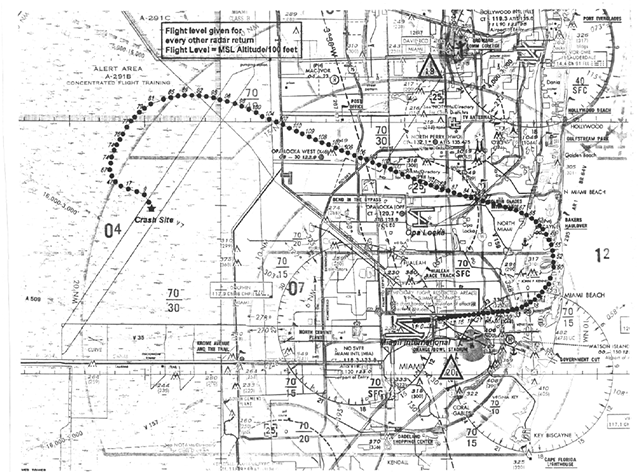

Map of Accident Site, from

NTSB Report, Figure 1

There is no cause for finding fault in anything the pilots did or did not do. The circumstances doomed them to their fates. But we pilots should take a few lessons here:

- We cannot simply assume those loading our aircraft, or even those walking on to our aircraft, have done everything possible to ensure we are HAZMAT free. It is the nature of our jobs to make air travel easy for our passengers and where we draw the line between being intrusive about what they've packed and being completely invisible in this regard is up to you. But you should be alert for any signs that HAZMAT has been loaded.

- You should be especially wary if your company doesn't have very obvious and plainly evident HAZMAT procedures. If you want a compelling read about just how the system can be stacked against you, read The Lessons of ValuJet 592 by William Langewiesche. The blame goes to the FAA and while the companies involved could have done better, the pilots and line personnel were powerless to stop this.

The flight lasted ten minutes and all on board were doomed the minute the oxygen generators were put on board. In the corporate world we are at the mercy of whatever our passengers bring on board by way of packed luggage but should still be on the lookout for obvious HAZMAT.

1

Accident report

- Date: 11 MAY 1996

- Time: 14:13

- Type: McDonnell Douglas DC-9-32

- Operator: ValuJet Airlines

- Registration: N904VJ

- Fatalities: 5 of 5 crew, 105 of 105 passengers

- Aircraft Fate: Destroyed

- Phase: En route

- Airports: (Departure) Miami International Airport, FL (MIA) (MIA/KMIA), United States of America; (Destination) Atlanta-William B. Hartsfield International Airport, GA (ATL) (ATL/KATL), United States of America

2

Narrative

We, as an industry, have learned a lot since ValuJet 592. Our aircraft are better equipped and procedures for dealing with HAZMAT have improved. If your aircraft has a baggage or cargo compartment that you cannot access while in flight, you need to be even more leery about what has been loaded. But even if your baggage compartment is just behind the cabin, having to deal with any kind of fire while in flight is not good.

- On May 11, 1996, at 1413:42 eastern daylight time, a Douglas DC-9-32 crashed into the Everglades about 10 minutes after takeoff from Miami International Airport (MIA), Miami, Florida. The airplane, N904VJ, was being operated by ValuJet Airlines, Inc., as flight 592. Both pilots, the three flight attendants, and all 105 passengers2 were killed. Visual meteorological conditions existed in the Miami area at the time of the takeoff. Flight 592, operating under the provisions of Title 14 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) Part 121, was on an instrument flight rules flight plan destined for the William B. Hartsfield International Airport (ATL), Atlanta, Georgia.

- ValuJet flight 591, the flight preceding the accident flight on the same aircraft, was operated by the accident crew. Flight 591 was scheduled to depart ATL at 1050 and arrive in MIA at 1235; however, ValuJet’s dispatch records indicated that it actually departed the gate at 1125 and arrived in MIA at 1310. The delay resulted from unexpected maintenance involving the right auxiliary hydraulic pump circuit breaker.

- Flight 592 had been scheduled to depart MIA for ATL at 1300. The cruising altitude was to be flight level 350, with an estimated time en route of 1 hour 32 minutes. The ValuJet DC-9 weight and balance and performance form completed by the flightcrew for the flight to ATL indicated that the airplane was loaded with 4,109 pounds of cargo (baggage, mail, and company-owned material (COMAT)). According to the shipping ticket for the COMAT (see appendix C), the COMAT consisted of two main tires and wheels, a nose tire and wheel, and five boxes that were described as “Oxy Cannisters [sic]-‘Empty.’” According to the ValuJet lead ramp agent on duty at the time, he asked the first officer of flight 592 for approval to load the COMAT in the forward cargo compartment, and he showed the first officer the shipping ticket. According to the lead ramp agent, he and the first officer did not discuss the notation “Oxy Cannisters [sic]-‘Empty.’” on the shipping ticket. According to the lead ramp agent, the estimated total weight of the tires and the boxes was 750 pounds, and the weight was adjusted to 1,500 pounds for the weight and balance form to account for any late arriving luggage. The ramp agent who loaded the COMAT into the cargo compartment stated that within 5 minutes of loading the COMAT, the forward cargo door was closed. He could not remember how much time elapsed between his closing the cargo compartment door and the airplane being pushed back from the gate.

- Flight 592 was pushed back from the gate shortly before 1340. According to the transcript of air traffic control (ATC) radio communications, flight 592 began its taxi to runway 9L about 1344. At 1403:24, ATC cleared the flight for takeoff and the flightcrew acknowledged the clearance. At 1404:24, the flightcrew was instructed by ATC to contact the north departure controller. At 1404:32, the first officer made initial radio contact with the departure controller, advising that the airplane was climbing to 5,000 feet. Four seconds later, the departure controller advised flight 592 to climb and maintain 7,000 feet. The first officer acknowledged the transmission.

- At 1407:22, the departure controller instructed flight 592 to “turn left heading three zero zero join the WINCO transition climb and maintain one six thousand.” The first officer acknowledged the transmission. At 1410:03, an unidentified sound was recorded on the cockpit voice recorder (CVR), after which the captain remarked, “What was that?” According to the flight data recorder (FDR), just before the sound, the airplane was at 10,634 feet mean sea level (msl), 260 knots indicated airspeed (KIAS), and both engine pressure ratios (EPRs) were 1.84.

- At 1410:15, the captain stated, “We got some electrical problem,” followed 5 seconds later with, “We’re losing everything.” At 1410:21, the departure controller advised flight 592 to contact Miami on frequency 132.45 mHz. At 1410:22, the captain stated, “We need, we need to go back to Miami,” followed 3 seconds later by shouts in the background of “fire, fire, fire, fire.” At 1410:27, the CVR recorded a male voice saying, “We’re on fire, we’re on fire.”

- At 1410:28, the controller again instructed flight 592 to contact Miami Center. At 1410:31, the first officer radioed that the flight needed an immediate return to Miami. The controller replied, “Critter five ninety two uh roger turn left heading two seven zero descend and maintain seven thousand.” The first officer acknowledged the heading and altitude. The peak altitude value of 10,879 feet msl was recorded on the FDR at 1410:31, and about 10 seconds later, values consistent with the start of a wings-level descent were recorded.

Source: NTSB, ¶ 1.1

"Critter" was the ValuJet call sign.

- According to the CVR, at 1410:36, the sounds of shouting subsided. About 4 seconds later, the controller queried flight 592 about the nature of the problem. The CVR recorded the captain stating “fire” and the first officer replying, “uh smoke in the cockp... smoke in the cabin.” The controller responded, “roger” and instructed flight 592, when able, to turn left to a heading of two five zero and to descend and maintain 5,000 feet. At 1411:12, the CVR recorded a flight attendant shouting, “completely on fire.”

- The FDR and radar data indicated that flight 592 began to change heading to a southerly direction about 1411:20. At 1411:26, the north departure controller advised the controller at Miami Center that flight 592 was returning to Miami with an emergency. At 1411:37, the first officer transmitted that they needed the closest available airport. At 1411:41, the controller replied, “Critter five ninety two they’re gonna be standing (unintelligible) standing by for you, you can plan runway one two when able direct to Dolphin [an electronic navigational aid] now.” At 1411:46, the first officer responded that the flight needed radar vectors. At 1411:49, the controller instructed flight 592 to turn left heading one four zero. The first officer acknowledged the transmission.

- At 1412:45, the controller transmitted, “Critter five ninety two keep the turn around heading uh one two zero.” There was no response from the flightcrew. The last recorded FDR data showed the airplane at 7,200 feet msl, at a speed of 260 KIAS, and on a heading of 218o. At 1412:48, the FDR stopped recording data. The airplane’s radar transponder continued to function; thus, airplane position and altitude data were recorded by ATC after the FDR stopped.

- At 1413:18, the departure controller instructed, “Critter five ninety two you can uh turn left heading one zero zero and join the runway one two localizer at Miami.” Again there was no response. At 1413:27, the controller instructed flight 592 to descend and maintain 3,000 feet. At 1413:37, an unintelligible transmission was intermingled with a transmission from another airplane. No further radio transmissions were received from flight 592. At 1413:43, the departure controller advised flight 592, “Opa Locka airport’s about 12 o’clock at 15 miles.”

- The accident occurred at 1413:42. Ground scars and wreckage scatter indicated that the airplane crashed into the Everglades in a right wing down, nose down attitude. The location of the primary impact crater was 25° 55’ north latitude, 80° 35’ west longitude, or approximately 17 miles northwest of MIA.

Source: NTSB, ¶ 1.1

3

Analysis

Many have argued that this accident was a byproduct of deregulation and I suppose that is true. The more you subcontract, the more chance there is for error and certainly for reduced oversight.

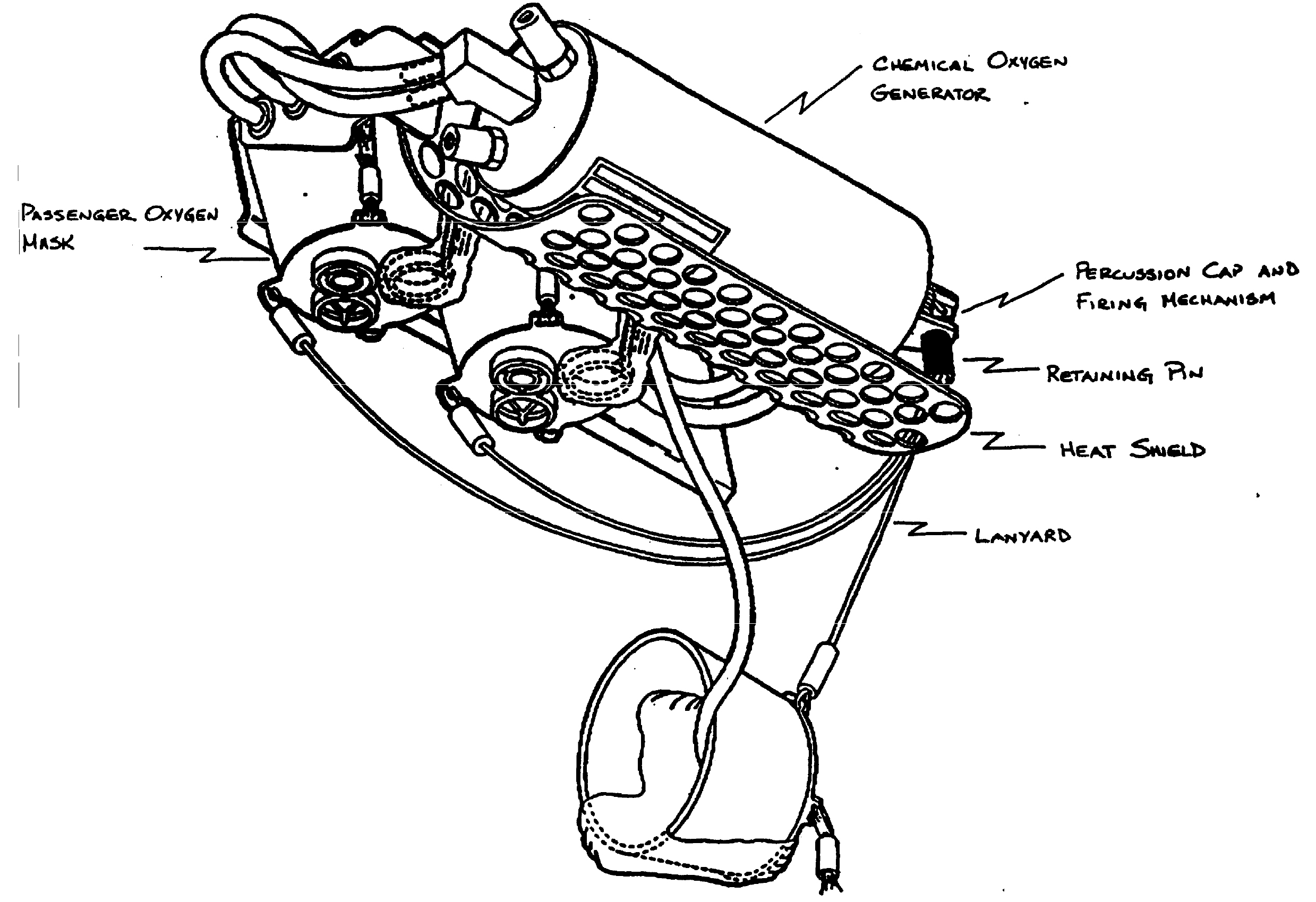

Diagram of passenger oxygen generator/mask installation, NTSB, figure 2a.

The MD-80 passenger emergency oxygen system is composed of oxygen generators that upon activation provide emergency oxygen to the occupants of the passenger cabin if cabin pressure is lost. The oxygen generators, together with the oxygen masks, are mounted behind panels above or adjacent to passengers. If a decompression occurs, the panels are opened either by an automatic pressure switch or by a manual switch, and the mask assemblies are released.

Source: NTSB, ¶ 1.1.2.1

- OXYGEN generators are safety devices. They are small steel canisters mounted in airplane ceilings and seat backs and linked to the flimsy oxygen masks that dangle in front of passengers when a cabin loses pressurization. To activate oxygen flow the passenger pulls a lanyard, which slides a retaining pin from a spring-loaded hammer, which falls on a minute explosive charge, which sparks a chemical reaction that liberates the oxygen within the sodium-chlorate core. This reaction produces heat, which may cause the surface temperature of the canister to rise to 500° Fahrenheit if the canister is mounted correctly in a ventilated bracket, and heating up. If there is a good source of fuel nearby, such as tires and cardboard boxes, the presence of pure oxygen will cause the canisters to burn ferociously. Was there an explosion on Flight 592? Perhaps. But in any event the airplane was blow torched into the ground.

- It is ironic that the airplane's own emergency-oxygen system was different—a set of simple oxygen tanks, similar to those used in hospitals, that do not emit heat during use. The oxygen generators in Flight 592's forward cargo hold came from three MD-80s, a more modern kind of twin jet, which ValuJet had recently bought and was having refurbished at a hangar across the airport in Miami. As was its practice for most maintenance, ValuJet had hired an outside company to do the job—in this case a large firm called SabreTech, owned by Sabreliner, of St. Louis, and licensed by the FAA to perform the often critical work. SabreTech, in turn, hired contract mechanics from other companies on an as-needed basis. It later turned out that three fourths of the people on the project were just such temporary outsiders.

Source: Langewiesche

- Chemical oxygen generator removal and installation practices and procedures are contained in the Douglas MD-80 maintenance manual and on the ValuJet MD-80 work card 0069. Passenger oxygen insert unit maintenance practices are delineated in the Douglas MD-80 maintenance manual. ValuJet provided these documents to SabreTech, and copies of each document were present at SabreTech at the time the generator removal and configuration changes on N802VV and N803VV were performed.

- The Douglas MD-80 maintenance manual, chapter 35-22-03 (PASSENGER OXYGEN INSERT UNITS--MAINTENANCE PRACTICES), provides a six-step procedure for removing the oxygen insert units from the passenger overhead environmental panels. Step 2 of that removal procedure states, “If generator has not been expended, install safety cap over primer.” ValuJet work card 0069 refers to this maintenance manual chapter in a “Note” under step #1 (“Remove Generator”), stating, “Passenger overhead environmental panels contain unitized oxygen insert units. If generator is to be replaced in these units, remove and replace insert unit (Reference: MM Chapter 35-22-03).” Work card 0069 delineates a seven-step process for removal of a generator. Step 2 states, “If generator has not been expended, install shipping cap on firing pin.”

- Following the accident, the Safety Board reviewed another air carrier’s work card (Alaska Airlines), issued before the ValuJet accident, for the task of removing chemical oxygen generators from MD-80s. The card contained a warning about the dangers of the unexpended generators and instructions to discharge the generators before disposal. This air carrier’s work card called for the discharge of all removed generators, and included instructions about the method for discharging them. It also identified the discharged generators as hazardous waste. The air carrier’s card stated, “Expended canisters are hazardous waste and require a hazardous waste label on the canister or on the container holding the expended canisters.” The card also called specifically for the expended generators to be held at the location where they were removed and directed the individuals performing the removal task to “. . . immediately notify the environmental affairs manager.”

Source: NTSB, ¶ 1.1.2.2

- About the middle of March 1996, SabreTech crews began removing the passenger oxygen insert units from both N802VV and N803VV and replacing the expired and near-expired generators with new generators. These units contained the oxygen generator, generator heat shield, mask retainer, and masks. The inserts were reinstalled after the masks were inspected, and the old generators were replaced with new generators.

Source: NTSB, ¶ 1.1.2.3

SabreTech, Inc. of Miami, Florida was an FAA-certified 14 CFR 145 domestic repair station.

- SabreTech maintenance records did indicate that six three-mask oxygen generators were removed from N830VV because they had been accidentally expended and required replacement but that the remaining generators on this airplane were not removed.

- Of the approximately 144 oxygen generators removed from N803VV and N802VV, approximately 6 were reported by mechanics to have been expended. There is no record indicating that any of the remaining approximately 138 oxygen generators removed from these airplanes were expended.

Source: NTSB, ¶ 1.1.2.3

- The activation of one or more chemical oxygen generators in the forward cargo compartment of the airplane initiated the fire on ValuJet flight 592. One or more of the oxygen generators likely were actuated at some point after the loading process began, but possibly as late as during the airplane’s takeoff roll.

- Even if the fire did not start until the airplane took off, a smoke/fire warning device would have more quickly alerted the pilots to the fire and would have allowed them more time to land the airplane.

- If the plane had been equipped with a fire suppression system, it might have suppressed the spread of the fire (although the intensity of the fire might have been so great that a suppression system might not have been sufficient to fully extinguish the fire) and it would have delayed the spread of the fire, and in conjunction with an early warning, it would likely have provided time to land the airplane safely.

- The loss of control was most likely the result of flight control failure from the extreme heat and structural collapse; however, the Safety Board cannot rule out the possibility that the flightcrew was incapacitated by smoke or heat in the cockpit during the last 7 seconds of the flight.

- The pilots did not don (or delayed donning) their oxygen masks and smoke goggles, and in not donning this equipment, they were likely influenced by the absence of heavy smoke in the cockpit and the workload involved in donning the type of smoke goggles with which their airplane was equipped.

- Given the potential hazard of transporting oxygen generators and because oxygen generators that have exceeded their service life are not reusable, they should be actuated before they are transported.

- Had work card 0069 required, and included instructions for, expending and disposing of the generators in accordance with the procedures in the Douglas MD-80 maintenance manual, or referenced the applicable sections of the maintenance manual, it is more likely that the mechanics would have followed at least the instructions for expending the generators.

- The failure of SabreTech to properly prepare, package, and identify the unexpended chemical oxygen generators before presenting them to ValuJet for carriage aboard flight 592 was causal to the accident.

Source: NTSB, ¶ 3.1

4

Cause

- The National Transportation Safety Board determines that the probable causes of the accident, which resulted from a fire in the airplane's class D cargo compartment that was initiated by the actuation of one or more oxygen generators being improperly carried as cargo, were (1) the failure of SabreTech to properly prepare, package, and identify unexpended chemical oxygen generators before presenting them to ValuJet for carriage; (2) the failure of ValuJet to properly oversee its contract maintenance program to ensure compliance with maintenance, maintenance training, and hazardous materials requirements and practices; and (3) the failure of the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) to require smoke detection and fire suppression systems in class D cargo compartments.

- Contributing to the accident was the failure of the FAA to adequately monitor ValuJet's heavy maintenance programs and responsibilities, including ValuJet's oversight of its contractors, and SabreTech's repair station certificate; the failure of the FAA to adequately respond to prior chemical oxygen generator fires with programs to address the potential hazards; and ValuJet's failure to ensure that both ValuJet and contract maintenance facility employees were aware of the carrier’s “no-carry” hazardous materials policy and had received appropriate hazardous materials training.

Source: NTSB, ¶ 3.2

References

(Source material)

Langewiesche, William, The Lessons of ValuJet 592, The Atlantic, March 1998.

NTSB Aircraft Accident Report, AAR-97/06, In-flight Fire and Impact with Terrain, ValuJet Airlines Flight 592, DC-9-32, N904VJ, Everglades, Near Miami, Florida, May 11, 1996