I've lost more than a few squadron mates over the years to CFIT and in each case the cause was obvious after the event, but predicting the crash was almost impossible because these were perfectly good pilots flying perfectly good aircraft into the ground. Over the years we've made the perfectly good airplanes even more perfect and every time I fly my G450 with synthetic vision over rugged terrain I marvel at how perfect they've become. So that leaves us with the pilot.

— James Albright

Updated:

2017-09-15

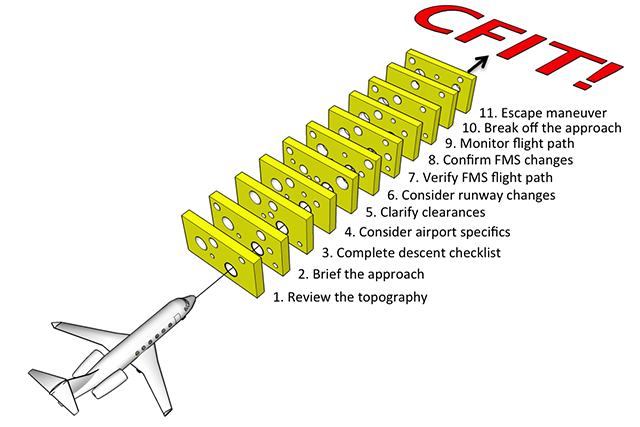

I hate the academician's view of our chosen profession as much as the next pilot, and I particularly disdain the Swiss cheese model for explaining things gone wrong. But in the case of CFIT, it actually works. So we'll take a look at each slice of cheese here, in hopes that we can learn something along the way and have at least one of those slices prevent the next CFIT.

3 — Complete the Descent Checklist

4 — Consider Airport Specifics

You can also download the Flight Safety Foundation CFIT Checklist.

1

Review the Topography

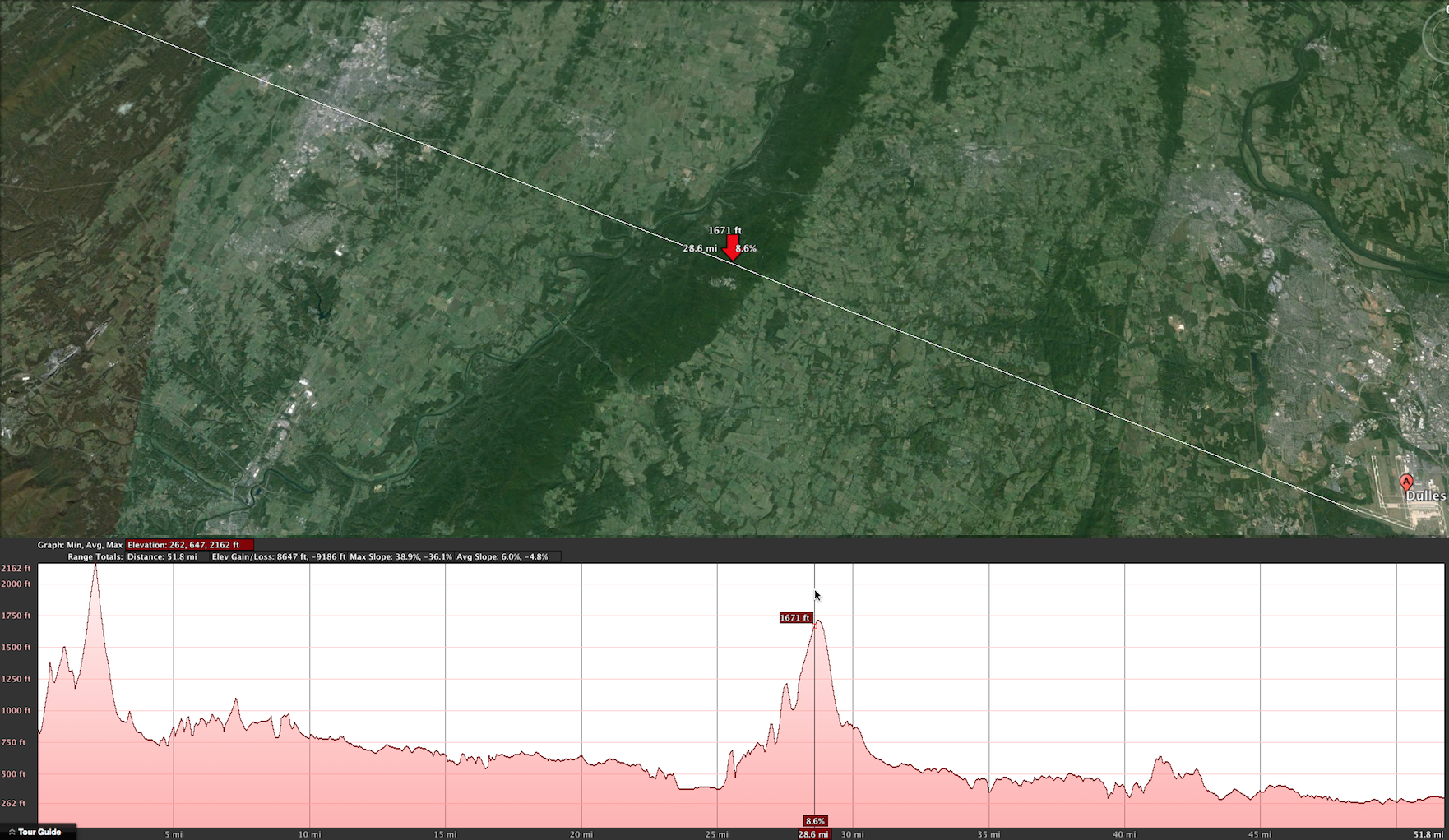

We spend a lot of time in areas we aren't familiar with and we don't always have an instinctual idea of where the mountains are. Not many airlines or corporate operators equip their crews with terrain charts but having an idea where the terrain is in relation to your approach and departure paths is critical. The case of Trans World Airlines 514 is more than just the pilots not knowing there was terrain 25 nm west of the airport, it was also about them not instinctually understanding that it doesn't make sense to descend to the final approach fix altitude 44 nm away from the runway. This was in 1974 and EGPWS would have definitely helped. But the crew was not situationally aware of the terrain.

More about this: Trans World Airlines 514.

Another example: Korean Air Lines 642.

Making a thorough mental review of the characteristics of every takeoff and approach.

Source: Flight Safety Digest, pg. 18, Item 1

At the very least your cockpit should have a detailed atlas to give you an idea where the rocks are. If your cockpit gives you a visual display of terrain on the instruments, you should know how to interpret and use that information.

2

Brief the Approach

The approach briefing sets the tone for the approach to come and should include terrain considerations. Many of us fail to give complete approach briefings when we expect visual conditions, "this will be a visual approach backed up by the ILS." In the case of the GIII that killed all on board on approach into Aspen in March of 2001, the captain never gave an approach briefing because he expected visual conditions. His poorly flown approach ended with the crew losing sight of the runway and killing all on board.

More about this: Gulfstream III N303GA.

Performing a comprehensive briefing for every takeoff and approach. The briefing should be tailored for the specific takeoff or approach, and the briefing should include both expected and unexpected items. The pilot conducting the briefing should explicitly request feedback from the other pilot.

Source: Flight Safety Digest, pg. 18, Item 2

3

Complete the Descent Checklist

The approach briefing should be made at a time close enough to the actual approach so that it is fresh in both pilots' memories, but with enough time to conduct a thorough briefing without the distractions of managing the descent. A few pointers from over the years:

- The pilot monitoring should have everything set up — radios tuned, courses set, FMS programmed — before the briefing, so as to be able to pay attention during the briefing.

- The pilot flying the approach should give control of the aircraft to the other pilot while briefing, so as not to be distracted by the requirements of flying the airplane.

- Ideally, the briefing should be done in level flight before the descent has begun. But if altitude and course changes are needed during the briefing, remember the roles of the left and right seat pilots may have changed from PF to PM and the reverse. The PF flies the airplane, after all.

Properly completing all checklists. Airlines should consider including the approach review and briefing as part of the descent checklist.

Source: Flight Safety Digest, pg. 18, Item 3

4

Consider Airport Specifics

There is a long history of Korean Air pilots relying on an ILS glide slope and crashing their airplanes when the glide slope was missing. That was certainly the case of Korean Air 801. But a contributing factor was the pilots not understanding that when the controller said "glide slope unusable" they were being given a key piece of information.

More about this: Korean Air 801.

Correctly following ATC rules and procedures, especially those that could relate to CFIT accidents.

Source: Flight Safety Digest, pg. 18, Item 4

If you don't use a particular airport on every trip, you may need a refresher course. When flying to a foreign destination we often study the airport pages intently, so as not to miss anything vital. We should give that same respect to domestic airports too. Your first flight into Chicago O'Hare should be given the same attention to detail you would give Paris Le Bourget. By the same token, Teterboro arriving Runway 06 Circle 01 is a completely different airport than Teterboro arriving ILS 19.

5

Clarify Clearances

N807FT, Aviation Safety Network

- The controller instructed: "Tiger 66, descend two four zero zero. Cleared for NDB approach runway three three."

- The pilot heard "descend to four zero zero" and read back: "Okay, four zero zero."

- The correct phraseology would have been: "descend and maintain two thousand four hundred feet" from the controller and the pilot.

The clearance was to 2,400 feet and the crew descended TO 400 feet. Everyone on board was killed and the aircraft was destroyed.

More about this: Flying Tiger Line 66.

Detecting ambiguous clearances and resolving them with questioning, paraphrasing and clarifying communications.

Source: Flight Safety Digest, pg. 18, Item 5

6

Consider Runway Changes

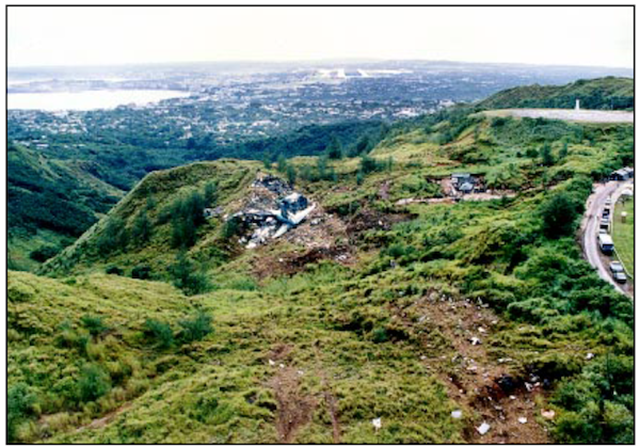

While there were a lot of mistakes going on with the case of Air China 129, all would have been saved had the crew understood why their aircraft required Category D minimums for circling and why they were not familiar with landing operations on the opposite runway. When the runway changed the captain noted: "We won't enlarge the traffic pattern, the mountains are all over that side." But neither pilot considered their aircraft was simply incapable of making the turn and most on board perished.

More about this: Air China 129.

Carefully evaluating runway changes by ATC. Changes should be refused unless the crew is prepared mentally for the new approach and can accomplish the new tasks without becoming distracted or absorbed. New approaches should be rejected unless the crew is confident that they can make a stabilized approach.

Source: Flight Safety Digest, pg. 18, Item 6

We often get a last minute runway change and pride ourselves with being able to roll with the punches. But if the change is to a runway we've never used or will require an instrument approach to minimums using an approach we haven't briefed, it may be time for a holding pattern to sort things out.

7

Verify FMS Paths

You should never allow the aircraft's navigation system to point the airplane someplace both pilots haven't already agreed upon. The guy programming the box is normally busy with a stack of duties when the course change comes up and may not be as actively engaged in the business of pointing the airplane correctly as the guy doing the flying. Two pilots are less likely to make a mistake than one pilot, so both pilots need a vote on FMS changes. Depending on aircraft equipment, there are several options to get both pilots in the loop before the aircraft reacts.

Verifying the appropriateness of CDU changes and obtaining confirmation of the changes by the PF before executing the changes.

Source: Flight Safety Digest, pg. 18, Item 7

Execute Key

Some aircraft provide a graphic presentation of what the change in flight path will look like before the change is actually made with an "Execute" button on the FMS. This, in my book, is optimal.

Confirm / Activate Prompts

Some aircraft provide a graphic presentation of what the change in flight path will look like before the change is actually made, depending on how the change is made. In the G450, as shown in the photo, a change made on the MAP display draws the new path over the old and displays a "ACTIVATE / UNDO / CANCEL" prompt. Unless using initiated transfer (more on that below), a change made on the G450 MCDU may or may not give you a confirmation step, depending on the type of change and if the change impacts the current leg.

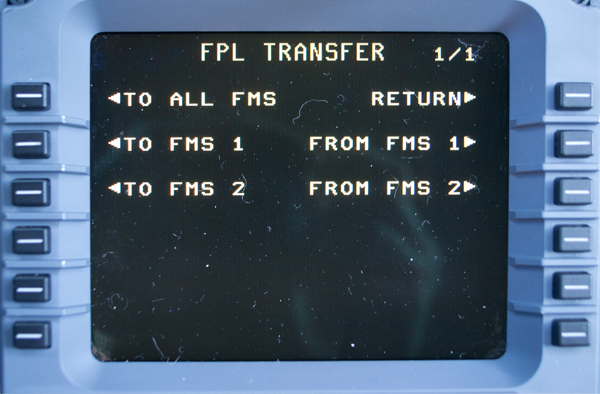

Initiated Transfer

Back in the GIV and GV about one in a hundred pilots used initiated transfer; it seems the only ones using it are those that got burned by the aircraft blindly following a bad key stroke or, like me, heard about somebody violated for the same reason. The G450 and G550 are better off, provided the pilots make their changes on the DU MAP display when they can and take other precautions (see Scratch Pad Approval, below) when they can't.

If you are a skeptic, you should try it for just one flight. In the GV it means three extra key strokes per change. That may seem like a bother until one day it saves you from turning the airplane into a mountain.

Scratch Pad Approval

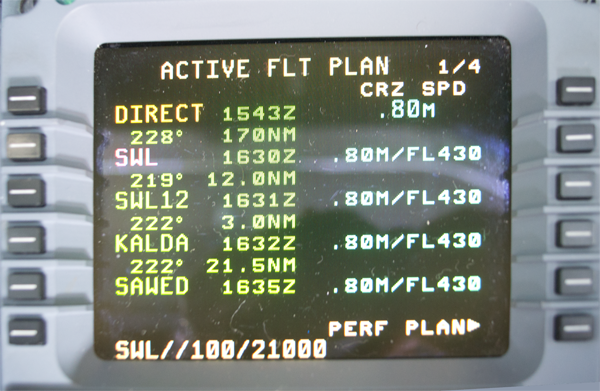

If you don't have a map display activate option, an FMS execute key, or even an initiated transfer ability between FMS, you can still take precautions. In fact, even if you have all that stuff you may still have situations where this technique is needed. I call it "scratch pad approval" because sometimes you build the change into the scratch pad and ask the other pilot to check your work before entering it into the FMS. In the example the PM has built a line that will place a VNAV point 100 nautical miles north of SWL at FL 210. The PM points to LSK 2L, the PF agrees, then the PM presses the correct key.

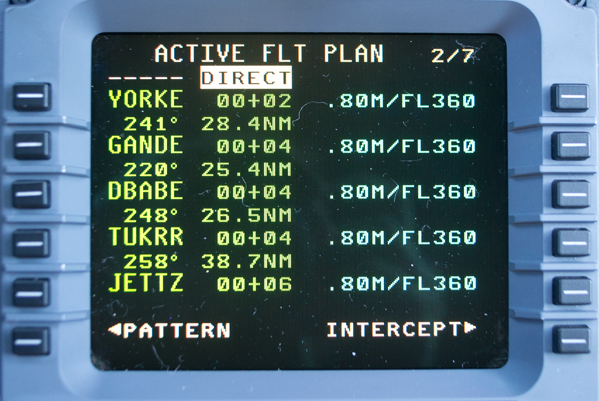

Sometimes you just need to build what you can before it becomes permanent and hover your "execute finger" over the correct key and ask the other pilot to approve. In the example the PM already pressed the DIR key to command a direct leg and will hover his finger over LSK to command a direct leg to waypoint DBABE. The PF approves and the PM then presses the key.

8

Confirm FMS Changes

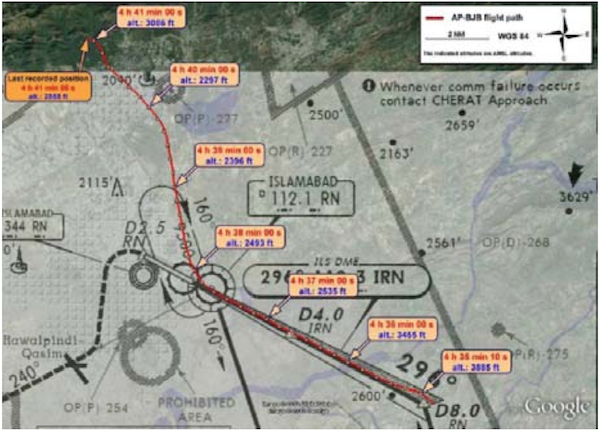

The captain of Air Blue Flight 202 had made more than his share of mistakes on the way to impacting the ground. One of many was spinning the heading select knob trying to avoid mountains ahead, while still in a lateral navigation mode.

More about this: Air Blue ABQ 202.

Verifying the appropriateness of CDU changes and obtaining confirmation of the changes by the PF before executing the changes.

Source: Flight Safety Digest, pg. 18, Item 8

Sometimes it isn't obvious what the airplane should be doing after a change is made to the FMS, flight director, or autothrottles. Nevertheless, you need evidence the requested change has had the intended effect before moving on.

Even after both pilots have agreed on a change to the lateral or vertical navigation they must still verify the aircraft understands the intended change and executes correctly. Never make a change without following up to see the autopilot, autothrottles, and flight director do as you meant. The mistake could be your programming or it could be the electrons. In either case, it is up to you to catch the error.

Do you see the error in the G450 guidance panel in the photo above? It is a common airplane-induced error that can put your airplane in the dirt.

9

Monitor Flight Path

Ensuring that one pilot always is monitoring and controlling the flight path of the aircraft.

Source: Flight Safety Digest, pg. 18, Item 9

The minute air traffic control says "cleared for the visual approach," we let our guard down and assume the approach and landing are as good as done. As bad as that tendency is, there is another that claims even more pilots. The second the pilot flying says "I have the runway" on an instrument approach, we again let our guard down. Visual illusions are at their worst in fog and that's when we need to keep the instruments in our scan. The one and only Gulfstream to ever end up in the water was flying a perfectly good ILS with a perfectly good glide slope. Nobody was hurt but the aircraft was destroyed.

More about this: GIII VP-BLN.

10

Break off the Approach

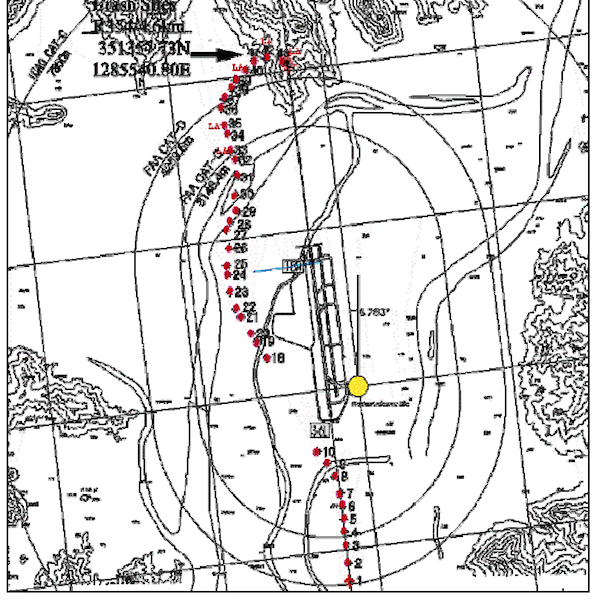

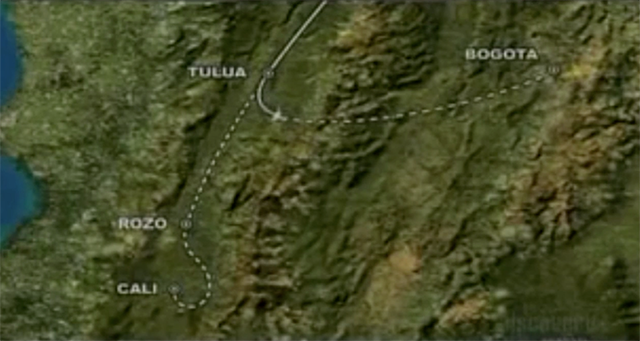

The CFIT that shocked the airline world, American Airlines Flight 965, was the first demonstration of how even the best technology is for naught when the pilots don't have a good mental picture of the terrain threat. The crew ended up in the wrong valley and a turn to the airport killed them and all but four of their passengers. The crew expressed concern several times about not knowing where they were.

More about this: American Airlines 965.

Discontinuing the approach whenever disorientation, confusion or uncertainty of position occurs.

Source: Flight Safety Digest, pg. 18, Item 10

From the Colombia Accident Report:

- Again at 2139:30, two minutes before impact, neither flight crew member could determine which navaid they were to proceed towards. The first officer stated, "left turn, so you want a left turn back around to ULQ." The captain replied, "Nawww...hell no, let's press on to..." The first officer stated, "well we're, press on to where though?" The captain replied, "Tulua." The first officer staid, "that's a right Tulua."

- The captain stated, "where we goin'? one two.. come to the right. let' go to Cali first of all, lets, we got [expletive] up her didn't we." The first officer replied, "yeah."

If you know you are lost, confused, or behind — especially in an terrain rich environment — climb.

11

Escape Maneuver

You must obviously refer to your aircraft manufacturer's recommendations, the G450 procedures may or may not provide a few techniques worth consideration, but there are some points to be made:

- Step 1 in the G450 procedure calls for the autopilot to be disconnected and it is hard to argue with that. I don't think any autopilot can cope with the aggressive CFIT escape maneuver.

- Step 1 of the G450 procedure also calls for "power to the mechanical forward limit." The G450 has a Full Authority Digital Engine Control (FADEC) system that protects the engine when "fire walled." In many aircraft the correct call here is "set max continuous."

- Step 2 requires the speed brakes are retracted but step 5 prohibits retraction of the landing gear and flaps. This has been the case on every aircraft I've flown with a CFIT escape maneuver.

- Step 3 call for a rotation rate of 3 to 4 degrees per second. Gulfstream is quiet on the reason but aircraft in my distant past were known to stall out the wing when pitch was yanked hard enough to "swap ends."

- Step 3 and 4 have you rotate until VREF and shoot for V2/VREF - 20 knots. VREF in a G450 is 1.3 VS and the wing continues to produce lift deep into the stick shaker.

More about this: Low Speed Flight.

Quickly and accurately applying the manufacturer's GPWS procedures in the event of a GPWS warning. The PNF should ensure performance of the correct procedures.

Source: Flight Safety Digest, pg. 18, Item 11

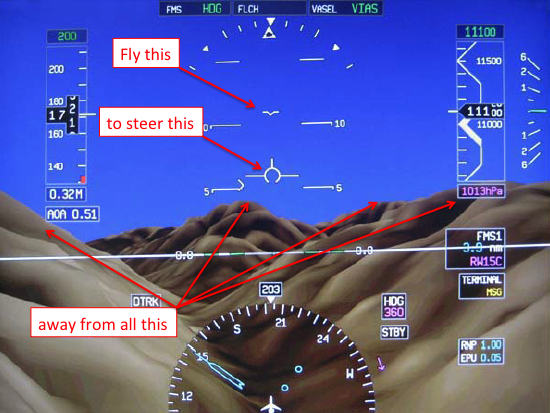

If your aircraft has an option for synthetic vision and you control your flight department's budget, allow me to make a buying recommendation: synthetic vision offers the greatest safety advance for the dollar available today. If you are low to the earth with the stick shaker going off, wouldn't you like to trade your circa-1940 attitude indicator for this:

Why not just fly the flight path vector? That's what you do on an ILS, after all. Keep in mind it is an instantaneous readout of where the airplane is going, it will be jumping all around the place and if you chase it, you will be flying erratically enough to cost climb performance. Just smoothly fly the boresight as you would a "normal" airplane and watch how the flight path vector reacts. If it jumps into the terrain now and then, raise the boresight a little. Try this in the simulator, it only takes one try to understand why.

References

(Source material)

Bureau d'Enquetes et d'Analyses, Accident on February 6, 1998 at the Lac du Bourget (73) the aircraft Gulfstream G III registered VP-BLN, March 29, 1999.

Colombia Aeronautica Civil, Controlled Flight Into Terrain, American Airlines Flight 965, Boeing 757-223, N651AA, Near Cali, Colombia, December 20, 1995 (Prepared by University of Bielefeld, Germany

Flight Safety Foundation, CFIT Checklist, Rev. 2.3/1,000/r, 1994

Flight Safety Foundation, Flight Safety Digest, Boeing 757 CFIT Accident at Cali, Columbia, Becomes Focus of Lessons Learned, May-June 1998

Korea Aviation Accident Investigation Board Report, AAR F0201, Controlled Flight Into Terrain, Air China International Flight 129, B767-200ER, B2552, Mountain Dotdae, Gimhae, April 15, 2002

Mayday: Lost, Cineflix, Episode 4, Season 2, 20 February 2005 (American Airlines 965)

NTSB Aircraft Accident Report, AAR-00/01, Korean Air Flight 801, Boeing 747-300, HL7468, Controlled Flight Into Terrain, Nimitz Hill, Guam, August 6, 1997

NTSB Aircraft Accident Brief, AAB-02/03, Avjet Corporation, Gulfstream III, N303GA, Aspen, Colorado, March 29, 2001

Pakistan Civil Aviation Authority Safety Investigation Board, Air Blue Flight ABQ-202 REG AP-BJB Pakistan Crashed on 28 July 2010 at Margalla Hills, Islamabad