The glamour days of the test pilot are long gone. It makes absolutely no sense to strap on an airplane that has never flown before, go up there an "punch a hole in that thar envelope." These days all the hard work is done by computers and when millions of dollars are involved, no manufacturer wants to rush the process. But the myth continues and many flight test pilots I've known over the years bandy the title about with a swagger worthy of a Tom Wolfe novel

— James Albright

Updated:

2015-04-28

Why is this important to us? Because we quite often get called upon to do what is more properly called a functional check flight. That's where the aircraft has been worked on and you need to ensure it still performs the way the flight manual says it should. They are also required in some countries before an aircraft is sold. During my time in the Air Force I had FCF duties in the Boeing 747 and the Gulfstream III and both of these programs had specific rules and extensive manuals to keep everyone safe. You had to have a fair amount of experience and an engineering degree was a plus; but being a disciplined, no nonsense pilot was mandatory. Here's a story about one of my functional check flights with a little bit of Air Force bureaucracy thrown in: "No Plan Survives the Enemy".

In the civilian name-brand, big-airplane world, things are much the same. Boeing and Airbus tightly control who can do these and how they are done. I know the Boeing program has strong military influences and I would not be surprised if the same were true at Airbus.

In the business aircraft side of the house it is a different story. Gulfstream and Bombardier do not publish FCF manuals, do not have specified rules on how to accomplish FCFs, and anyone can take the airplane for a spin and do one. The formal program they use to test their own aircraft are not as tightly controlled as they should be and the pilots may or may not have formal training. Their mishaps tend to be covered up, unless they go horribly wrong and government agencies have to get involved. Two such mishaps: Challenger 604 C-FTBZ and Gulfstream G650 N652GD.

You could very well be called upon to do a functional check flight in your business jet and those that came before you will say it is no big deal. You may start to believe that, because the pilot who had the task before you was nothing special. How hard can it be? I recommend you read about my first civilian experience with this: "I've never been so scared". And then you should get serious about the task at hand.

1

Functional Check Flights (FCF) vs. test flights

In any aviation company which is too small to have a dedicated staff of pilots trained to perform flight checks on aircraft, there is real danger when presented with an airplane that has just come through some maintenance and needs to be evaluated. This could be as simple as taking the airplane to a compass rose to make sure the heading instruments work, to as complicated as taking the airplane to altitude to make sure an engine will relight once shut down. It is vitally important that everyone involved understand the difference between these functional check flights and the stuff of movies and novels. After a few accidents, the European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) came up with the best definition of a functional check flight:

EASA

- For the purpose of this SIB, a functional check flight is any non-revenue flight performed to assess or demonstrate aircraft serviceability, for in service aircraft already having a valid certificate of airworthiness. This could be a flight after maintenance or before lease transfer, or troubleshooting checks on the ground where the aircraft is operated by a flight crew.

- The core business of an operator may not necessarily include the conduct of such flights on a regular basis; thus, the level of expertise to conduct these flights safely may not be available.

Source: EASA SIB

- Different definitions for FCF

- Operational Check Flight: Flight where aircraft need to be checked for proper operational functioning.

- Maintenance Check Flight: Continuing airworthiness task.

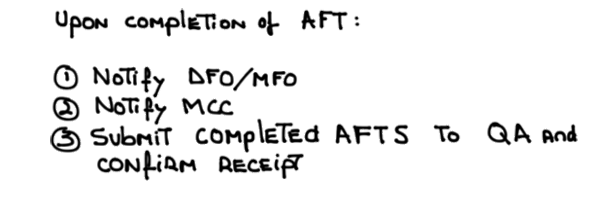

- Acceptance Flight: Defined in the Acceptance Flight test schedule (AFTS). Its purpose is to perform a general check of the aircraft systems.

- Test flight: flight performed after special maintenance and/or repair work on an aeroplane and on special request of the authority.

- Multiple definitions of FCF

- Cover a very large scope of flights.

- Flights going from checks of radios to a check of general behaviour of the aircraft.

- Boundary between FCF and flight testing has to be well defined.

Source: EASA Perspective

U.S.

The term "functional check flight" indicates that the flight is conducted to a test standard. The term "operational check" flight, as referenced in section 91.407(b), is a more appropriate term when referring to verification that the maintenance performed on the aircraft was accomplished to approved standards of repair and that the aircraft is operational.

Source: FSAW 02-12, pg. 1

The bottom line here is that a functional check flight is used to ensure the airplane, or one of its systems, is working up to the standards in the flight manuals.

Regulatory

From the FAA's perspective, a flight test is a very big deal and requires approval . . .

Flight tests.

(a) Each applicant for an aircraft type certificate (other than under §§21.24 through 21.29) must make the tests listed in paragraph (b) of this section. Before making the tests the applicant must show—

(1) Compliance with the applicable structural requirements of this subchapter;

(2) Completion of necessary ground inspections and tests;

(3) That the aircraft conforms with the type design; and

(4) That the Administrator received a flight test report from the applicant (signed, in the case of aircraft to be certificated under Part 25 [New] of this chapter, by the applicant's test pilot) containing the results of his tests.

(b) Upon showing compliance with paragraph (a) of this section, the applicant must make all flight tests that the Administrator finds necessary—

(1) To determine compliance with the applicable requirements of this subchapter; and

(2) For aircraft to be certificated under this subchapter, except gliders and except airplanes of 6,000 lbs. or less maximum certificated weight that are to be certificated under Part 23 of this chapter, to determine whether there is reasonable assurance that the aircraft, its components, and its equipment are reliable and function properly.

(c) Each applicant must, if practicable, make the tests prescribed in paragraph (b)(2) of this section upon the aircraft that was used to show compliance with—

(1) Paragraph (b)(1) of this section; and

(2) For rotorcraft, the rotor drive endurance tests prescribed in §27.923 or §29.923 of this chapter, as applicable.

(d) Each applicant must show for each flight test (except in a glider or a manned free balloon) that adequate provision is made for the flight test crew for emergency egress and the use of parachutes.

(e) Except in gliders and manned free balloons, an applicant must discontinue flight tests under this section until he shows that corrective action has been taken, whenever—

(1) The applicant's test pilot is unable or unwilling to make any of the required flight tests; or

(2) Items of noncompliance with requirements are found that may make additional test data meaningless or that would make further testing unduly hazardous.

(f) The flight tests prescribed in paragraph (b)(2) of this section must include—

(1) For aircraft incorporating turbine engines of a type not previously used in a type certificated aircraft, at least 300 hours of operation with a full complement of engines that conform to a type certificate; and

(2) For all other aircraft, at least 150 hours of operation.

Source: 14 CFR 21, § 21.35

Tests: aircraft.

(a) Each person manufacturing aircraft under a type certificate only shall establish an approved production flight test procedure and flight check-off form, and in accordance with that form, flight test each aircraft produced.

(b) Each production flight test procedure must include the following:

(1) An operational check of the trim, controllability, or other flight characteristics to establish that the production aircraft has the same range and degree of control as the prototype aircraft.

(2) An operational check of each part or system operated by the crew while in flight to establish that, during flight, instrument readings are within normal range.

(3) A determination that all instruments are properly marked, and that all placards and required flight manuals are installed after flight test.

(4) A check of the operational characteristics of the aircraft on the ground.

(5) A check on any other items peculiar to the aircraft being tested that can best be done during the ground or flight operation of the aircraft.

Source: 14 CFR 21, § 21.127

2

Guidance

- EASA recommends operators, intending to conduct flights and manoeuvres that could be classified as functional check flights, to seek advice from the competent authorities (European NAAs in charge of their oversight, or EASA for design-related issues) and from the type certificate holder of the aircraft.

- The operator should also establish:

- A flight operational risk assessment specific to functional check flights;

- Risk mitigation measures including operating procedures for such flights as expanded in the Operating Manual.

- EASA further recommends that the following be clearly communicated to all personnel involved:

- the intentions of the functional checks;

- the way the functional checks are intended to be performed;

- procedures that are different or in addition to standard operating procedures; and

- roles and responsibilities of all personnel involved.

- Such flights should only be performed by crew with appropriate knowledge, experience and training.

Source: EASA SIB

- EASA recommends operators, intending to conduct flights and manoeuvres that could be classified as functional check flights, to seek advice from the competent authorities (European NAAs in charge of their oversight, or EASA for design-related issues) and from the type certificate holder of the aircraft.

- The operator should also establish:

- A flight operational risk assessment specific to functional check flights;

- Risk mitigation measures including operating procedures for such flights as expanded in the Operating Manual.

- EASA further recommends that the following be clearly communicated to all personnel involved:

- the intentions of the functional checks;

- the way the functional checks are intended to be performed;

- procedures that are different or in addition to standard operating procedures; and

- roles and responsibilities of all personnel involved.

- Such flights should only be performed by crew with appropriate knowledge, experience and training.

If you are flying a Boeing or an Airbus, there is guidance out there to help you with just about every task you have to complete. You just need to ask. If you are flying just about any business aviation aircraft, you may have some work to do. But you do have options. For the sake of illustration, let us consider something I've had to do three times: perform and acceptance flight after a major item of the airplane's flight control system had been replaced.

- Ask the aircraft manufacturer for a detailed procedure. They have to do these so it stands to reason they ought to have a procedure you can use.

- Refuse to fly the airplane until the manufacturer provides an acceptable alternative. Some manufacturers don't have written procedures or are unwilling to share these procedures for unknown reasons. You can turn the tables and say the airplane is parked until they fix it.

- Write your own flight check procedure. With aircraft flight and maintenance manuals in front of you, you can put together a flight check procedure that will make everything that you do in the air more methodical and well thought out, meaning they will be safer. It will also bring to light areas where your knowledge is lacking, where you need to do more research or get outside help. More about this: Writing an FCF procedure.

I had both rudders replaced on a Boeing 747 and they provided a flight check procedure that detailed what had to be done (a high speed controllability check and a series of approach to stall maneuvers) as well as specific guidance on how to fly each maneuver.

The problem with most manufacturers is that they are reluctant to provide procedures for liability issues and would probably prefer you have them provide pilots to do them. Many will refer you to procedures given in maintenance manuals and those often work well. But these manuals are often neglected, out of date, and can have errors.

I was flying a Challenger 604 around 2002, when it got hit on the ramp by a BBJ. The horizontal stabilizer had to be replaced and Bombardier released it without a check flight. We refused to fly it and our company's CEO called the Bombardier CEO and said he was going to make a public announcement that we were getting out of the Challenger business and finding another aircraft type. The next day a Bombardier "test pilot" showed up. Unfortunately, he was completely clueless, which led us to the next option . . .

In the case of our broken Challenger, the company pilot said he had never had to deal with a new horizontal stabilizer and didn't have any ideas on how to do it. We sat down and decided the tail would affect controllability at low and high speed and might be suspect under G-loading. So we can up with procedures to check each. (More about how to do this coming up.)

3

Risk management

The time to start managing the risk comes when the functional check flight is first proposed.

- Is an FCF really necessary? First check to see if the test or data can be acquired on the ground. With today's computer driven aircraft, many fewer flight tests are required than in the past. However, sometimes the only time a malfunction occurs is in flight and/or the only way to duplicate conditions is by putting the aircraft at altitude. Since there is no practical way to duplicate flight loads, aircraft flexing, temperatures and pressures on the ground, sometimes only a flight check will do.

- Is it required by the maintenance manual? There are very few times when the maintenance manual requires a flight check. If a flight is required, specific checklists and procedures will/should be provided by the manufacturer.

- In most cases a demonstration flight using normal procedures and a normal flight profile should suffice. If something beyond a strictly normal flight profile is required, take care with FCF crew composition.

- If the manufacturer will not provide a specific procedure and one is not available in the maintenance manual, Writing an FCF procedure should be done well in advanced and passed around to knowledgeable resources for critique.

- The FCF sortie should be flown in good weather, day conditions and with easily understood rules and criteria for completion and abort.

- All FCF personnel should review a few FCF Mishap Case Studies to understand that poorly planned and executed functional check flights can go horribly wrong if not approached with a due for safety.

Operation after maintenance, preventive maintenance, rebuilding, or alteration.

(a) No person may operate any aircraft that has undergone maintenance, preventive maintenance, rebuilding, or alteration unless—

(1) It has been approved for return to service by a person authorized under §43.7 of this chapter; and

(2) The maintenance record entry required by §43.9 or §43.11, as applicable, of this chapter has been made.

(b) No person may carry any person (other than crewmembers) in an aircraft that has been maintained, rebuilt, or altered in a manner that may have appreciably changed its flight characteristics or substantially affected its operation in flight until an appropriately rated pilot with at least a private pilot certificate flies the aircraft, makes an operational check of the maintenance performed or alteration made, and logs the flight in the aircraft records.

(c) The aircraft does not have to be flown as required by paragraph (b) of this section if, prior to flight, ground tests, inspection, or both show conclusively that the maintenance, preventive maintenance, rebuilding, or alteration has not appreciably changed the flight characteristics or substantially affected the flight operation of the aircraft.

Source: 14 CFR 91, § 91.407

- In accordance with the regulatory sequence of section 91.407(a), a maintenance release of the aircraft must be accomplished first before an operational check flight is conducted. This maintenance release can be either an entry in the logbook or the air carrier maintenance release form.

- Section 91.407(b) permits an operator (e.g., air carrier) two options to verify the accomplishment of the previously performed maintenance.

- An operational check flight can be performed if any of the maintenance, preventive maintenance, rebuilding, or alterations may have appreciably changed the flight characteristics or substantially affected the aircraft flight operations. If any additional maintenance is required following an operational check flight, then the aircraft is returned to maintenance, requiring a new maintenance release to service.

- The operator or air carrier may opt not to conduct an operational check flight by verifying the performance of the aircraft maintenance through ground checks or inspections, if appropriate.

Source: FSAW 02-12, pg. 2

- Approximately 25% of accidents involving turbine powered aircraft during the past decade have occurred during non-revenue flights (e.g., ferry flights for maintenance purposes or re-positioning flights to pick-up passengers). During this same period, the technology needed for an airline to download and analyze FDR data has become significantly more accessible, either through the airline's acquisition of more affordable FDR data acquisition and analysis technology, or through the use of readily available vendor services.

- Discussion: Two common factors found by the National Transportation Safety Board to have been contributory in non-revenue flight accidents are:

- the flightcrew's failure to adhere to standard operating procedures (SOPs) and,

- the flightcrew's failure to operate the airplane within its performance limitations.

- Flight Operational Quality Assurance (FOQA) programs presently in operation by most major U.S. airlines have clearly established the capability of FDR data analysis to objectively identify the occurrence of both such factors.

- Recommended Action: All air carriers operating under part 121 that have the capability to review FDR data, including in particular regional airlines, should place special emphasis on reviewing FDR data from non-revenue flights in order to verify that the flights are being conducted according to standard operating procedures (SOP). If FDR analysis indicates a potential trend of SOP non-compliance during such flights, that information should be communicated to appropriate airline management personnel for action to mitigate associated risks. If FDR data indicates noncompliance on the part of an individual crew, it is recommended that the information be communicated to the Chief Pilot and, if applicable, to Professional Standards group in the labor association, for the purposes of crew contact discussion, counseling and safety education.

Source: SAFO 08024

Check flights are performed to determine whether an aircraft and its various components are functioning according to predetermined specifications while subjected to the flight environment. Such flights are conducted when it is not feasible to determine safe or required operation (aerodynamic reaction, air loading, signal propagation, etc.) by means of ground or shop tests.

Source: Technical Order 1-1-300, ¶4.1

4

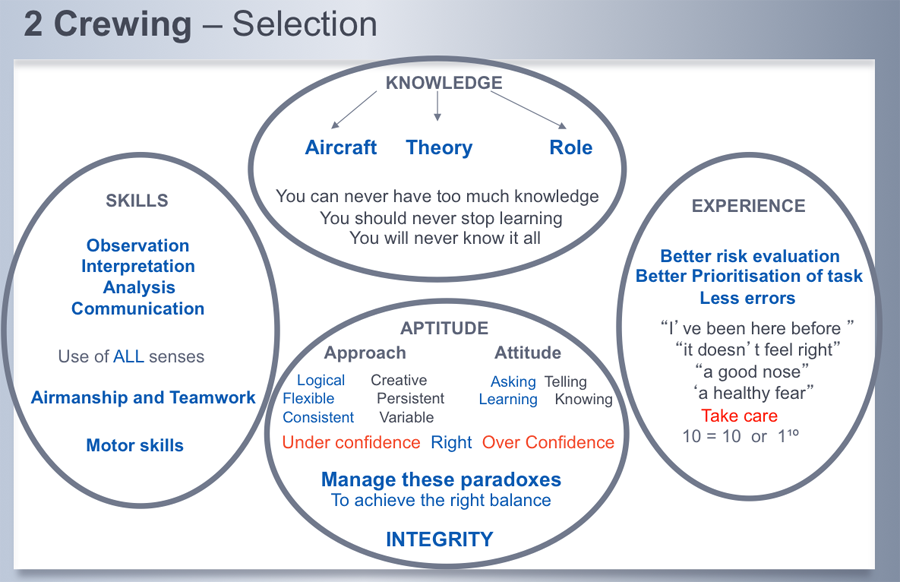

FCF crew composition

FCFs should be conducted with designated crew members that display the appropriate competencies, skill sets and experience. This does not mean the pilots with the best hands, the most total time, or the most fearless. (A healthy fear and appropriate caution with a dash of skepticism is often best.) The crew should be technically inquisitive, knowledgeable of aircraft systems, interrelationships, and restrictions, skilled in observation, interpretation and analysis. FCFs require better risk evaluation, prioritization of tasks, a high level of teamwork and above all, integrity. Each member of the crew should tolerate delays well.

- A small technical crew group

- Leadership

- Crew composition:

- Technical Flight Engineer

- Cabin specialists

- Selection Pros/Cons

- Good communicator . . . egotistical

- Technically inquisitive . . . uninterested

- Determined to get answers . . . indecisive

- Good flying ability . . . questionable integrity

- Admits errors and learns . . . takes criticism badly

- Takes responsibilities . . . avoids responsibility

- Patient . . . impatient

- Makes balanced judgements . . . inflexible

- "Defaults" towards safety . . . risk prone

- Team player . . . loner

Source: Airbus

The regulatory requirements to fly a test flight are quite high. For an FCF? Not so much . . .

Regulation 14 CFR section 91.407(b) states: "no person may carry any person (other than crewmembers) in an aircraft that has been maintained, rebuilt, or altered in a manner that may have appreciably changed its flight characteristics or substantially affected its operation in flight until an appropriately rated pilot with at least a private pilot certificate flies the aircraft, makes an operational check of the maintenance performed or alteration made, and logs the flight in the aircraft records."

Source: FSAW 02-12, pg. 3

5

Writing an FCF procedure

Resources

If your aircraft manufacturer doesn't have something called a "production aircraft test manual," a "customer acceptance manual," an "in service aircraft test manual," or anything like that, you may have to come up with your own FCF procedure. You have other sources of information available, such as the Airplane Flight Manual, Aircraft Operating Manual, or the Aircraft Maintenance Manual

- Associate warnings and limits with check to be done

- Hard limits need clear DO NOT EXCEED warnings

- Avoid writing a check sequence over two pages

- Make them easy to handle. Not too big or detailed

Source: Airbus

Example procedure — Provided by the manufacturer

A good example of a functional check flight procedure required outside the aircraft manufacturer's control is the Challenger 604 Air Driven Generator (ADG) test. The ADG is an emergency electrical power source that employs an automatically deploying generator attached to a propeller. The manufacturer has put together a well thought out procedure which adheres to much of the guidance presented here. The linked attachment is from many years ago and may not reflect the current procedure, but serves as a model for those writing their own procedures.

Example procedure: Challenger 604 Air Driven Generator In-flight Check.

Example procedure — Written by the operator

An example appears below.

6

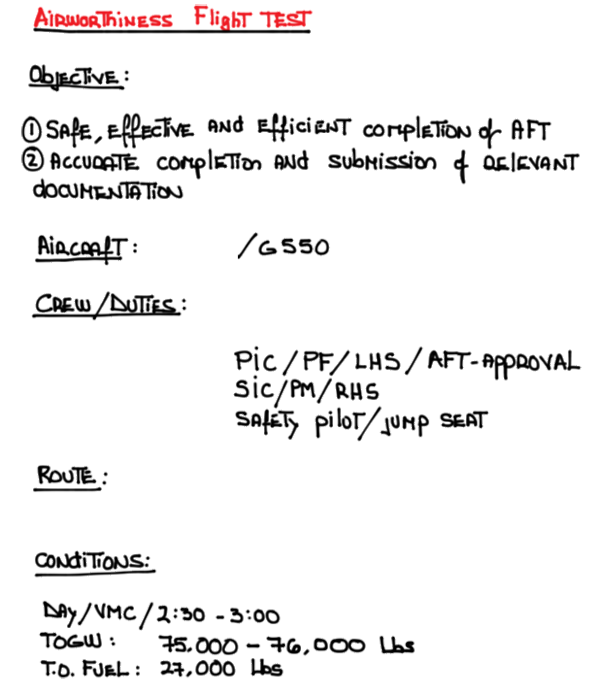

The FCF sortie

CRM for an FCF is different than for a routine flight. The aircraft should be flown by a three man crew. The Captain is the primary controls operator, responsible for the safety of the flight and is primary gatekeeper of the overall pacing, progress and conduct of the flight. The FO acts as communicator, systems operator, switch mover and works in concert with the Captain and the third crewmember, the flight test engineer (conductor, technical expert, etc.). The Flight Test engineer is a third pilot or maintenance technician that reads and runs the individual checks, takes copious notes and ensures that all required data is recorded and that the checks are conducted or aborted using the predetermined criteria. It is the engineer that sets the pacing of individual checklist items, ensuring that the aircraft has established the proper conditions and configurations. Switch movement is coordinated between the engineer and the FO, with consent of the Captain.

The number of people onboard the aircraft should be restricted to the absolute minimum. If an additional person is not required for the checks to be performed, the three man crew should be the only folks on board No passengers, straphangers, observers, sightseers, tourists, goats or self loading cargo should be on board. Additional folks lead to crew distraction, divided attention and possible interference with the purpose of the flight.

Purpose of the FCF procedure

Demonstrate that the aircraft:

- Conforms with the type and individual certificate to a Certificate of Airworthiness Standard

- Meets its specifications

- Meets the standards of quality required for delivery

Source: Airbus

Flight Preparation:

- The aircraft:

- What is the condition of the aircraft? Any MEL'd items or waivers?

- What were the disturbed systems? What areas of the aircraft were maintainers accessing?

- Were there any difficulties in the maintenance?

- What was the condition of the aircraft prior to maintenance?

- Were there any new maintenance procedures conducted?

- Are there any restrictions?

- Are the any required documents on board?

- The airfield:

- Are there any ground or flight restrictions/procedures dictated by the airport?

- Is fire coverage at primary and alternate airports sufficient?

- The airspace:

- Coordinate with ATC for the airspace that you will need for the conduct of the flight. See if a particular time of day would be advantageous.

- See if there is a preferred route for a normal flight profile or a MOA or other air work area that would work best if you need to delay in an area or get an altitude block to safely conduct flight checks.

- The weather:

- Daylight only.

- Ceiling and visibility criteria should be established based on the reason for the FCF. Most operators us basic VFR for all checks and higher (3500 / 3) for first flights or if avionics have been disturbed or are suspect. Criteria should be adjusted for any terrain or other peculiarities of the aerodrome.

- No icing or turbulence conditions. Gusts and crosswinds should have predetermined limits.

- No runway conditions or contamination.

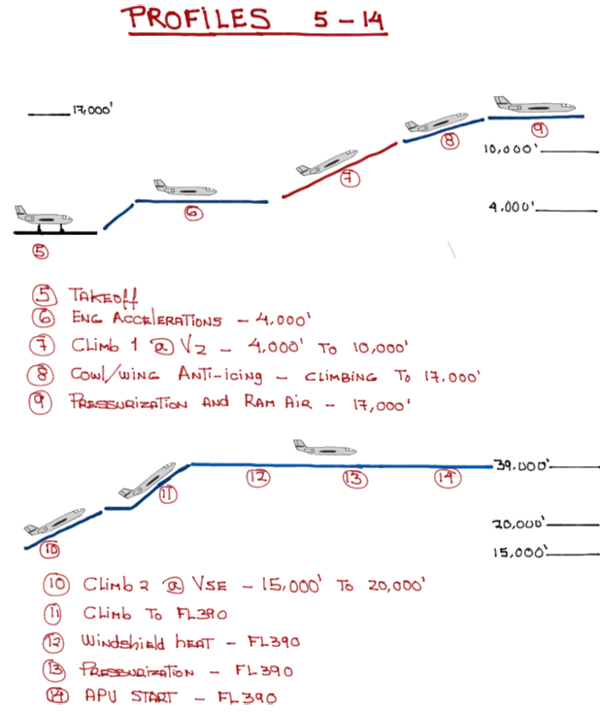

The profile:

- Fly a normal flight profile if at all possible. If there is not a compelling need for high speed / low speed handling characteristics or data recording, fly normal operational speeds. The same goes for altitude, bank angles, descent and climb rates, etc. Don't test for the sake of testing or just "seeing what it would do".

- Always stay within AFM limits.

- The flight should be meticulously planned, briefed, and "chair flown" by all crewmembers. There should be no doubt as to the sequence, limitations, preconditions, and "knock it off" criteria. If necessary, fly the entire test card in the simulator with all three crew. ( I think if the profile gets this deep, we would call in a production flight test crew from the manufacturer.)

- Have it in writing. The profile from preflight to debrief should be well planned and the specific sequence and conditions written down. Each test should have it's own test card (not longer than one page) that has each step, restrictions, conditions, notes, cautions, warnings and required data to be recorded explicitly spelled out. "Knock it off" criteria must be spelled out for each test.

There are many elements to master:

- Briefing

- Pre take-off

- Take-off

- Switching

- Communication

- Workload

- Different flight plans

- The day/night question

- Cabin systems

- More difficult check points

- Identify which check points carry more risk

- Pre flight, plan how to fly them and then stick to your plan

- Decide and brief "break off" points

- If things don't look right they are probably wrong – so stop

- Take care with breaks in the sequence

- Don't be tempted to "take a look" at certification test points

- Be failure minded and always consider your escape plan

Source: Airbus

Unexpected Results

Section 3, Tech 2, part 10 of the CAA Check Flight Handbook, published in April 2006, covering flying control checks states: ‘It might be possible to put some bank on the aircraft to turn a large pitch up or pitch down into a turn manoeuvre before re-powering the system. This might prevent an unusually high or low pitch manoeuvre developing.’ The CAA Check Flight Handbook also advises that where significant unexpected results are encountered no attempt should be made to rectify or explore them through experimentation or repetition.

Source: AAIB G-EZJK, pg. 7

7

FCF mishap case studies

One of the best ways of learning how to fly an FCF is to review the cases of those who did so poorly:

- Airbus A320-232 D-AXLA — Improperly painted and washed AOA transmitters lead to an airplane that doesn't fly as expected, and pilots who "ad hoc" a test procedure at low altitude.

- Boeing 737-73V G-EZJK — An improperly adjust elevator balance tab with a faulty company test procedure almost overcome very good, but inadequately trained, pilots.

- Challenger 604 C-FTBZ — Pilots poorly suited for the task mishandle takeoff rotation, destroying a perfectly flyable airplane.

- Falcon 2000 CS-DFE — Pilots not suited for an FCF displayed adequate caution about one factor of their ground tests, but not the most important factor.

- Gulfstream G650 N652GD — This flight test crew was killed by a management team more interested in selling airplanes with promised performance numbers than achievable numbers, and by a flight test organization without the integrity to say "no" when "no" was the correct answer.

I think I have done about twenty of these, mostly in the Boeing 747, some in the Challenger 604, and the rest in various Gulfstreams. I've only been surprised once in flight but there have been more than a few lessons along the way. Here are few:

- Review emergency procedures for all systems to be checked or areas disturbed by maintenance.

- An FCF walk-around is not a normal walk-around. Be extremely diligent and meticulous. Question everything.

- Make extensive use of ground checks. Make sure you get the response that you expect and that is required.

- If your avionics or flight data recorder provide a pilot event marker, use it. If something "interesting" happens on a FCF, mark it.

- Consider mounting a "Go Pro" camera securely in the cockpit to record the event. It will help you to recreate the sequence of events after you land.

- Do not trouble-shoot in flight.

- If a test fails, don't do it again "this time with gusto" to see if it will do it again.

8

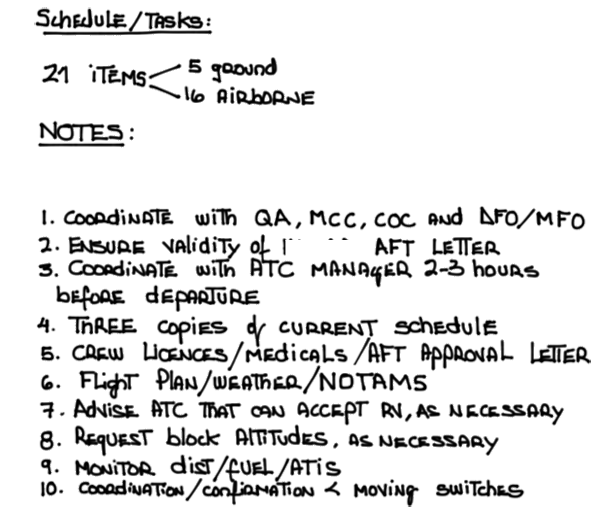

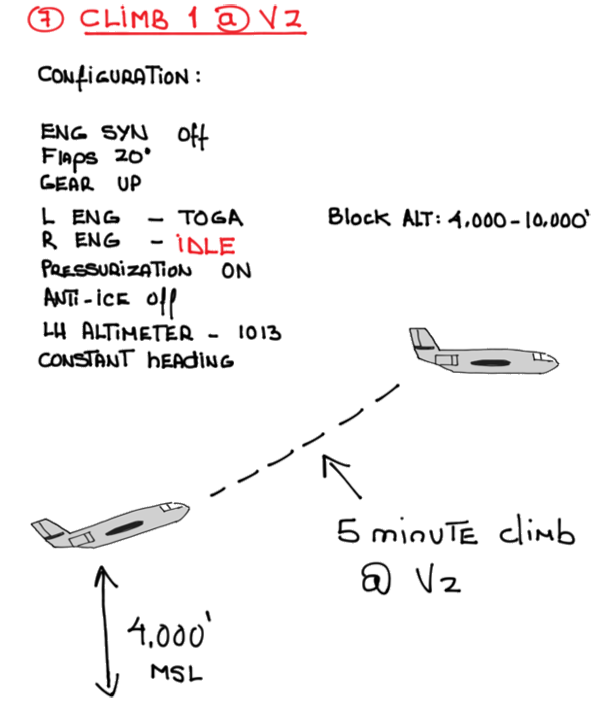

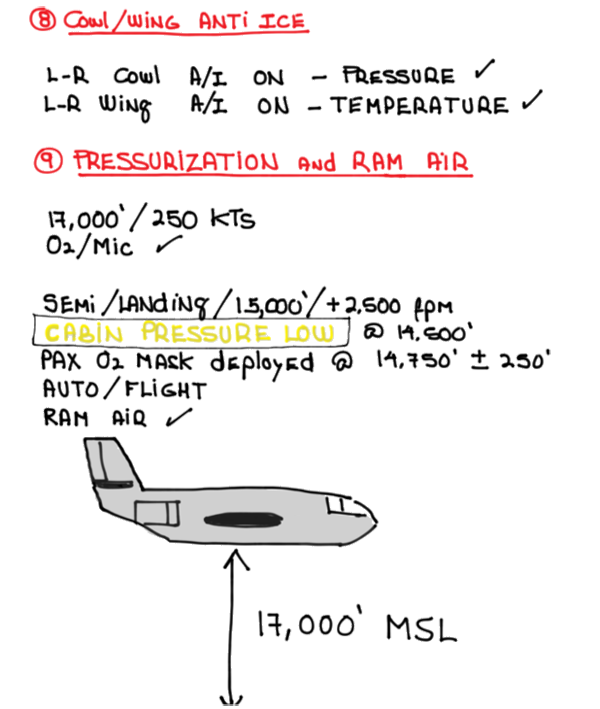

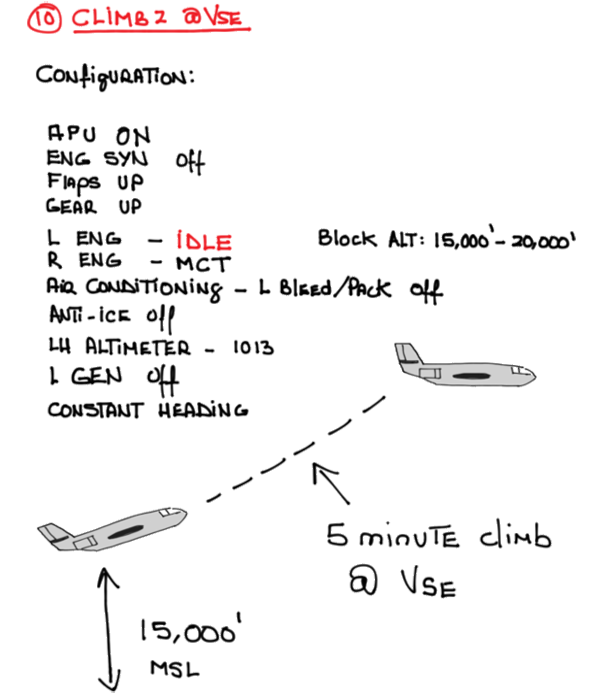

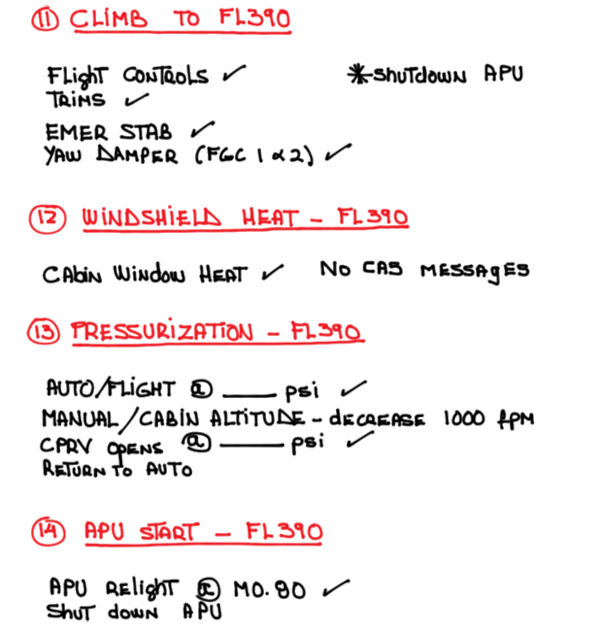

Example FCF cards

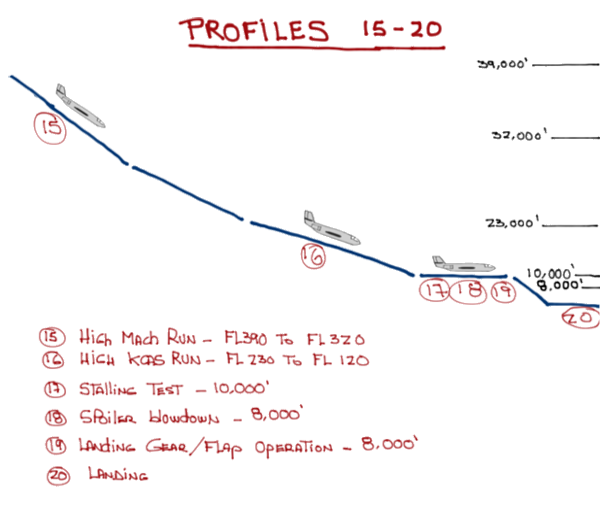

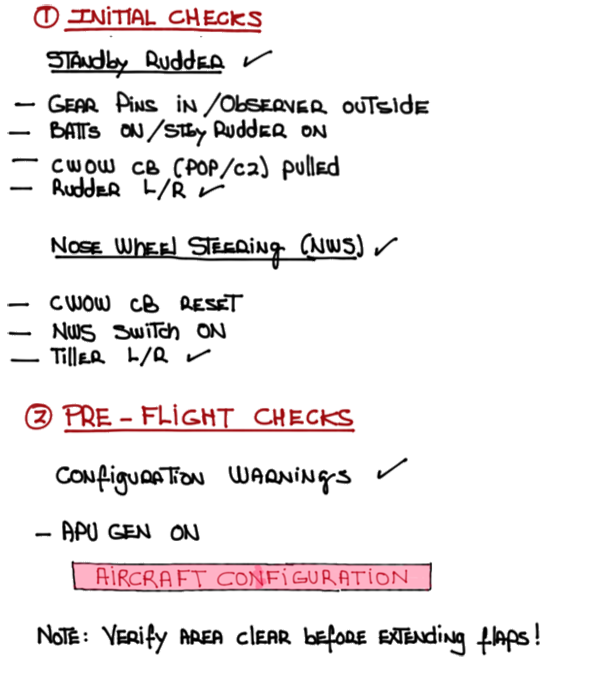

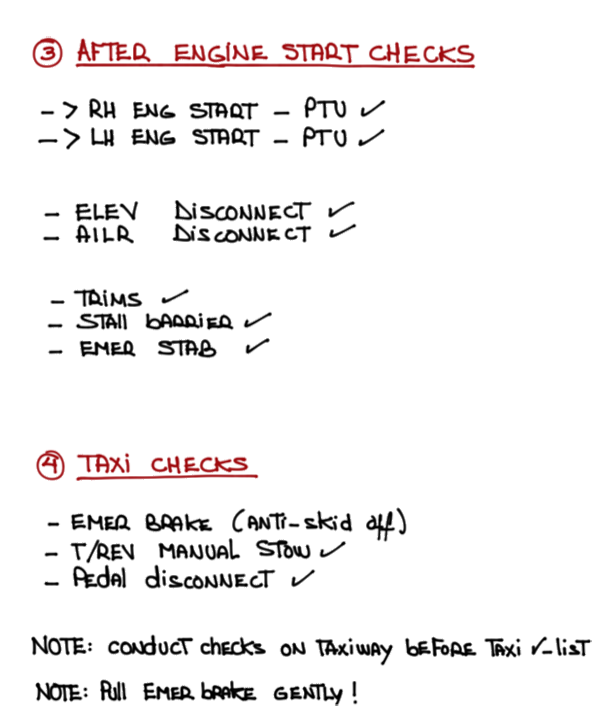

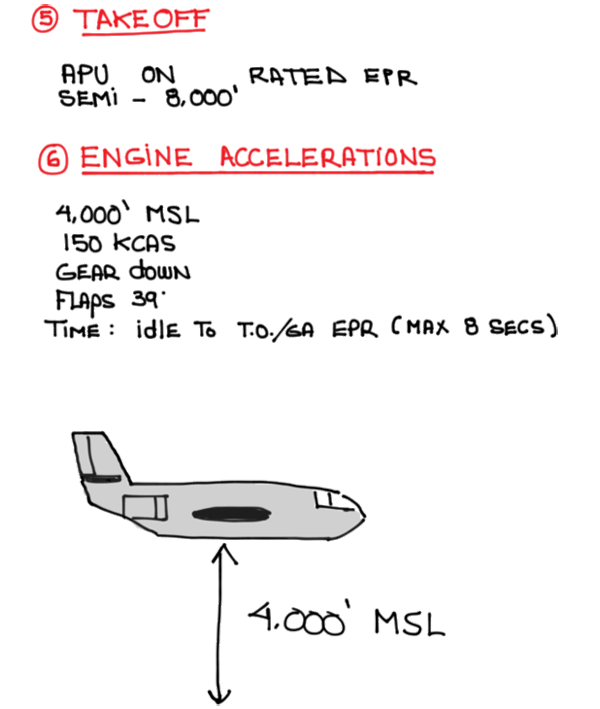

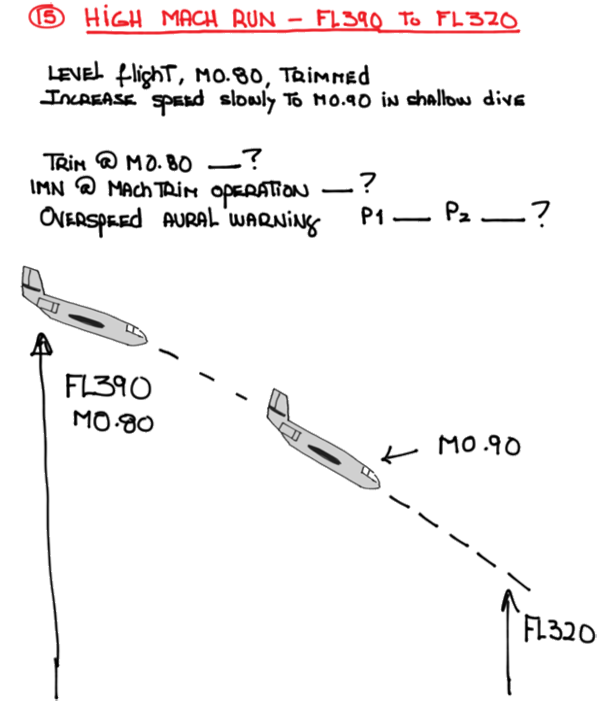

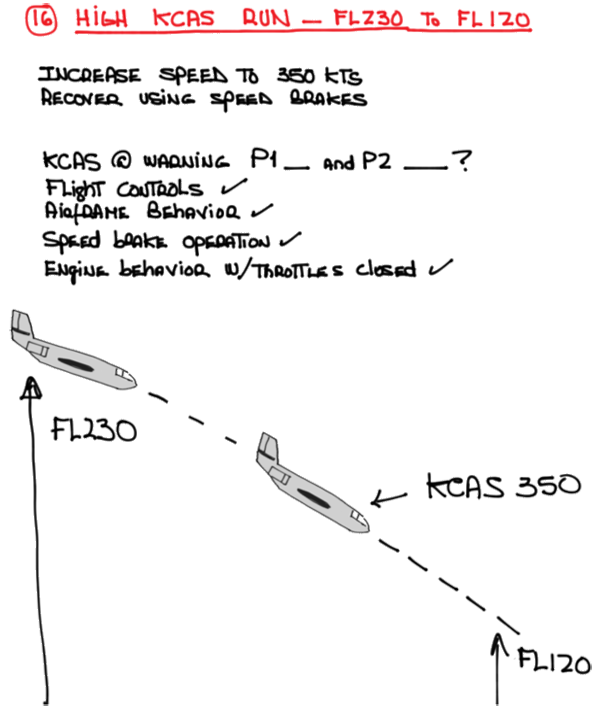

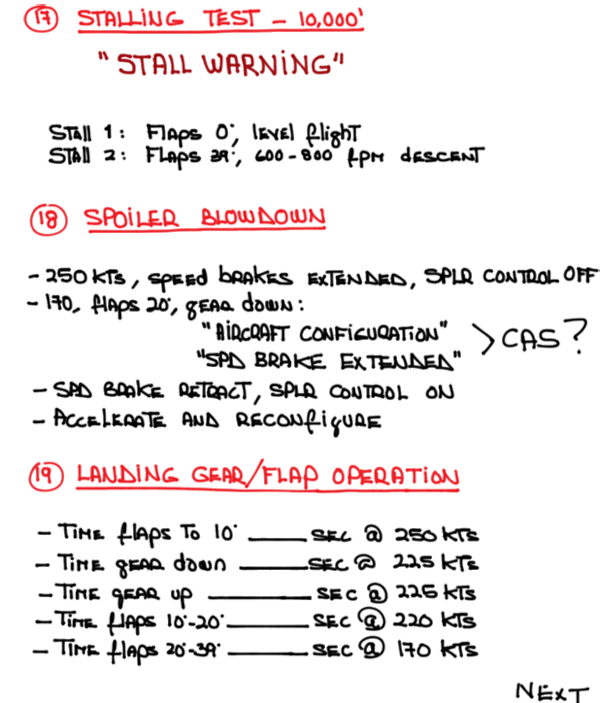

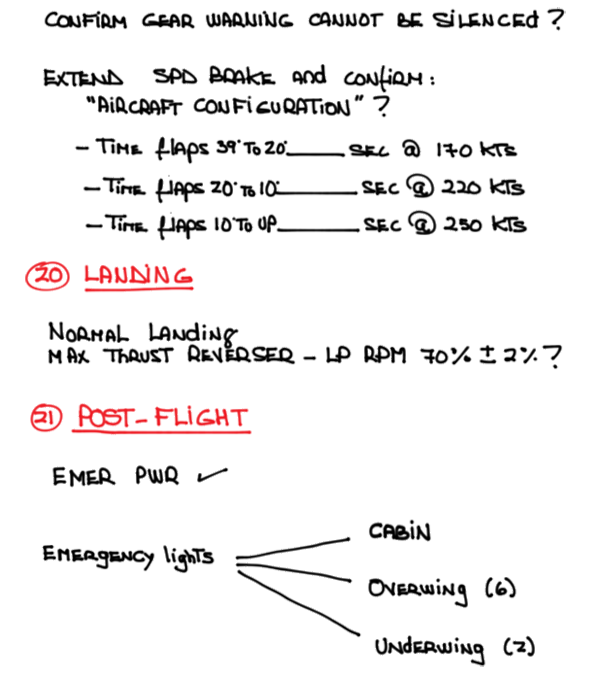

FCF's can be safely conducted with a minimum of risk and drama, provided the pilot running the show puts a lot of thought into the profile and is methodical. Ivan Luciani, a very professional G550 pilot, submits the following example cards. They are worth emulating.

References

(Source material)

14 CFR 21, Title 14: Aeronautics and Space, Certification Procedures for Products and Parts, Federal Aviation Administration, Department of Transportation

14 CFR 91, Title 14: Aeronautics and Space, General Operating and Flight Rules, Federal Aviation Administration, Department of Transportation

Air Accidents Investigation Branch, Serious Incident, Boeing 737-73V G-EZJK, 9/2010.

Challenger 604 Operating Manual, Publication No. CH 604 OM, Rev 56, Jan 14/05.

Functional Check Flight: EASA Perspective, the Functional Check Flight Symposium, Vancouver, 8 February 2011.

Functional Check Flights, EASA Safety Bulletin (SIB) No. 2011-07, 05 May 2011

Guidance Addressing Operational Check Flights Following Maintenance of Air Carrier Aircraft, Flights Standards Information Bulletin for Airworthiness (FSAW) 02-12, 12-31-02, FAA Order 8300.10, Appendix 4.

* Note that this FSAW has long expired, but the guidance remains sound so is included here for your consideration.

Safety Alert for Operators, SAFO 08024, Review of Flight Data Recorder Data from Non-revenue Flights, 12/10/08, U.S. Department of Transportation

Technical Flights - The Airbus View, Flight Safety Foundation, Presented by Captain Harry Nelson, undated.

Technical Order 1-1-300, Maintenance Operational Checks and Check Flights, Secretary of the Air Force, 15 March 2012.