The pilot breed has in it the primal instinct to attempt every assigned task, no matter the odds. Like many of our innate urges, this proclivity must be kept in check because in an airplane, it can be deadly. A commercial airline pilot certainly feels this pressure, but no pilot is at higher risk than a corporate pilot flying for a small number of regular passengers. Be they the business owners, senior executives, or even a private family, familiarity with one’s passengers places a pilot at increased risk. No matter how safety conscious or understanding the passengers are, the pilot feels pressure to say yes to every task.

— James Albright

Updated:

2020-11-02

There is an old saying in corporate aviation, “You don’t pay me to say yes, you pay me to say no.” Saying “yes” is easy; it is what they want to hear. It takes real courage to look at the person who controls your fate and say “no.” Unfortunately there is no easy recipe for giving pilots the necessary skills needed to say “no” and survive. Consider the following case studies; each a true story with a lesson in the art of saying “no.”

Just as individuals can become complacent and vulnerable to the “we’ve always done it that way” syndrome, so too can organizations lose focus on what really matters. There are natural opportunities to look at processes from the bottom up, such as after a change in leadership or a large turnover of pilots. Even without these events, however, opportunities can be invented. Each Safety Management System (SMS) audit presents such an opportunity every few years. Flight departments can also run internal audits. Each of these events presents an opportunity to reverse an earlier regretted “yes” into a wiser “no.”

Every case study reported here is a true story. In each instance, saying “yes” was the easy way out. It’s not that pilots consciously overlook rules, regulations, safety, and common sense. It’s that these pilots can talk themselves into thinking they are better than the rules, the rules don’t apply to everyone, or that “it will be all right this one time.” Saying “no” is difficult, takes courage, and could risk employment. But that’s why they pay you the big bucks.

Chris Manno, the person who draws many of the cartoons on this website and a retired airline pilot, has this to say:

"I’m looking for “no” when everyone else says “yes;” I’m saying stop when everyone else says go. The easiest thing in the world is to just let things happen, but the more important responsibility is in making them go exactly as they should–or not at all.”

—Chris Manno

1 — Case study: transfer ownership

2 — Case study: delay and redirect

4 — Case study: the safety card

5 — Strategies for "in the moment"

1

Case study: transfer ownership

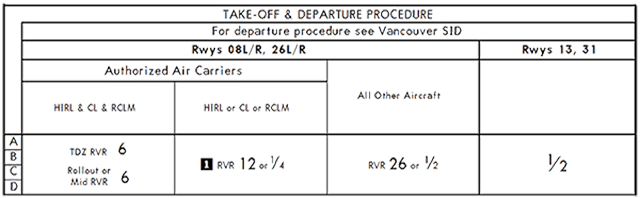

Vancouver International Airport takeoff minimums, from Jeppesen Airways Manual page CYVR 10-9A, 14 Aug 15

It was a quiet winter’s day in Vancouver, even more so at Vancouver International Airport (CYVR), which was shrouded in dense fog. Alan had already given the company chief executive officer a heads up, “You might as well sleep in; the fog has everyone grounded. I don’t think we can hope for enough visibility until 9 a.m. at the earliest.” The CEO, anxious to get home showed up early anyway and sat with his staff on the airplane waiting. After the visibility lifted to 600 feet RVR the sound of aircraft engines could be heard across the ramp. “At last!” the staff cheered.

“I’m sorry,” Alan said to his passengers, “the visibility is only 600 feet and the airport will only permit air carriers to takeoff until the visibility lifts to 2,600 feet.” The staff returned to their seats, dejected, but the CEO stood his ground.

“So you are telling me that if we were at home in Indianapolis,” he asked, “we could go?” “Yes,” Alan agreed.

“Well we are a U.S. airplane,” the CEO said. “Let’s go.”

Alan explained that not only could he lose his license for doing so, the company would risk a ban from Canadian airports, where many of their best customers were. The restriction was clearly printed on the Jeppesen airfield diagram and came directly from Transport Canada, their version of our FAA. The CEO agreed they had no choice. Fortunately the fog lifted in another hour and they made it home just a few hours late.

It isn’t clear if the CEO really intended his “let’s go” directive as an order to his pilot, but many pilots could have interpreted it that way. It may be that the CEO was testing the pilot, to see how firm he was in his convictions. Alan handled the situation well, calmly explaining the restriction was coming from the host country and ignoring it could have implications on the company’s business. He effectively transferred ownership of the word “no” to a higher power, the host nation’s government.

Pressure can come from more than just a business senior executive or an impatient staff. An aircraft owner or family member may coerce a pilot into exceeding personal or regulatory duty limits. A management company or charter operator can blindly push a pilot to flying a trip beyond the airplane’s comfortable range or into an ill-suited airport. This pressure can even come from fellow pilots or one’s chief pilot all too willing to please and overlook obvious safety issues. Sometimes the push comes in small doses and as each “no” becomes a “yes,” to push gets larger.

2

Case study: delay and redirect

As a young student pilot dreaming of flying jets, Ben had always considered the Learjet 35 to be a sure signal that a pilot had become an aviator. After years in the trenches he got his dream job flying for a private owner who used his Lear to fly friends and families to one vacation spot after another. Within a year Ben found himself on a first name basis with the owner and many of his passengers. In another year he realized another dream when he was made the chief pilot, running the two-pilot flight department. Right after his promotion, a new friend of the owner started spending more and more time in the cockpit, revealing that he too was a pilot. “What’s it like flying a jet?” “Does she land like my Piper?” “I sure would like a chance to fly her!”

At first the boss dropped a few subtle hints but after Ben politely said he couldn’t allow an untrained pilot to land the Learjet the request became an order. Ben asked for a little time and hashed it over with his co-captain and they both agreed it would be foolish to put a pilot with nothing larger than a PA-28 in his logbook in the seat for landing. The pilots considered their own paths to flying a jet and realized an hour in a full motion simulator might be enough to satisfy the request; it certainly couldn’t hurt. FlightSafety International offered a program tailor-made for executives who want to see what it is like flying a business jet and the passenger-pilot readily agreed to the hour in the box. Ben asked the simulator instructor to “be nice” but also to tie in many of the flight events with discussions about Learjet 35 mishaps just to drive home the fact not every airplane flies like a PA-28.

The boss’s favorite passenger was thrilled, and humbled, by the experience. “I think I’ll pass on flying the real thing,” he told the owner. “It really takes some skill to fly a Learjet! I really respect your pilots, Ben knows what he’s doing.”

Our case study pilot did a good job of delaying his answer and coming up with an alternative that diffused the situation. He also took the precaution of letting his co-captain understand the issues. The owner could have easily made the request to the second pilot and Ben could have very quickly found himself demoted or out of a job. Sometimes the art of saying “no” requires that the person receiving the message believes the person sending the message is sincere.

3

Case study: prioritize

Chris spent a few years flying for a regional airline with a poor safety record and learned firsthand what happens when corners are cut. He was on the ramp when another of his company’s aircraft started engines before getting the “all clear” signal from the ground crew. A mechanic was vacuumed off the ground by the Boeing 737’s engines and was lucky to survive, having lost most of his right arm. Chris vowed to never cut corners.

Years later Chris was one of three pilots in a small flight department flying Gulfstreams in the Northeast for a private company with a CEO who was habitually in a rush but usually late to the airplane. One day the CEO called with the orders, “have the right engine started by the time I get there, I want to be off the ground ASAP!”

“We don’t do that,” Chris explained. “That engine is like a big vacuum cleaner out there and we don’t run an engine when there are any people anywhere near it.” The CEO protested that the engine was unlikely to lift a person off the ground at idle power. “It doesn’t have to, all it takes is one loose piece of clothing to cause millions of dollars of damage.”

The CEO, while unhappy, let the subject drop. Chris mentioned the incident to each of his fellow pilots and each agreed to give the same answer. A year later another Gulfstream crashed at the same airport, killing all on board. “They rushed through their safety procedures,” the CEO explained to her staff. “I can tell you that our guys never do that,” she said proudly. “That’s why we hire only the best pilots.”

Chris was wise to use the phrase “we don’t” as opposed to “we can’t.” While the latter refusal hints there is room to give, the former says the speaker feels so strongly about it that there is no room for negotiation. Placing the value of the engine as well as the safety of each passenger above the need to hurry telegraphed the necessary message. But this was a case where saying “no” only cost the passenger a minute or two. What about for a case where “yes” has already been given and has become the normal operating procedure?

4

Case study: the safety card

Devon was a twenty-year Air Force pilot turned corporate captain flying for a leading technology firm in Houston, Texas. While he never thought of himself as a rigid “by the book” authoritarian, he had always tried to obey the letter and the spirit of the regulations. That’s why he was shocked to find out his first civilian flight department was routinely flying 16- to 18-hour duty days in a Challenger 604 from Torino, Italy back to Houston. “Well we used to come home from London in a day,” the dispatcher explained, “and that was no problem. Then we got an office in Munich and that put us right at our duty day limits if the winds cooperated. Then we started doing that all the time, no matter the winds. So Torino is only an extra hour. None of the pilots before you have ever complained.”

Devon flew the trip, thinking it best to show his “can do” attitude to his fellow pilots. If the other seven pilots could do it, he reasoned, there was no reason he shouldn’t be able to. On the day of the long trip back he felt himself nod off somewhere over the Midwest. His head jerked back and startled him back to consciousness. He looked to his left to see the captain sound asleep.

“I agree with you,” the chief pilot said when he brought the matter up at the next safety meeting. “But we’ve been doing this for a year now, if we tell the company we can no longer do this they are going to wonder if we’ve been doing something unsafe all this time.”

After some soul searching Devon decided it was worth losing his job rather than risk his license and his passenger’s safety over something so easily controlled. He let his boss know he would be looking for another job but was willing to stick around as long as needed for any trips that didn’t violate company duty rest policies. The chief pilot was shocked, especially when he heard from two more pilots moved to take the same stand. The chief pilot had no choice but to start scheduling crew swaps for the long duty days. To his surprise, nobody at the company headquarters objected.

We often paint ourselves into corners not realizing that the door is actually right behind us. In our duty day example, the company was unaware of any problems and the use of a crew swap en route was hardly noticed. Of course things could have gone very differently for Devon. As the previous case studies show, there are other techniques available before throwing down the safety card.

5

Strategies for "in the moment"

The process of saying “no” to someone above you in what the military calls the “chain of command” can be treacherous, even as a civilian. The result can be an increased respect for your integrity, courage, and abilities as an aviator. On the other end of the spectrum, however, you may find yourself unemployed. There is no cookie cutter solution, but there are a few paths leading to where you want to go.

Transfer ownership of the word “no”

If you can cite a law, regulation, or manual that forbids the intended action, you can effectively transfer ownership of the word “no.” It is no longer you saying “no,” it is the higher power. Be very careful to phrase this to emphasize your agreement with the law. In our low visibility example, commercial operators were allowed lower takeoff visibility minimums because the government exercises tighter control on commercial pilot training. “We train to the same standards because we believe in them, but we aren’t required to demonstrate them in a check ride every six months.”

For another example, let’s say you consider yourself grounded at an airport with a single runway with an unexpectedly strong crosswind. If your aircraft flight manual limits you to 24-knots, you say you are grounded because the crosswind exceeds the airplane’s demonstrated limit. “Bombardier says the conditions exceed the airplane’s capability and I can only trust their judgment on this; they built the airplane, after all.”

Delay and redirect

If you are surprised by a request, a polite request to “think about it” can help delay the eventual “no” to come. “It might be okay,” you could say, “but many things in aviation can be complicated and I want to make sure I’m not overlooking anything.” If your contemplation still leads you to the word “no,” coming up with a “yes” answer to a different question might be sufficient. In our passenger-pilot situation, a trip to the simulator was all it took to make the unreasonable request go away.

Prioritize

A “no” answer is often easier to take when the reason behind it is made clear. The very act of taking a hollow aluminum tube into the air seems closer to magic than science for most non-pilots. Sometimes the reasons for some of our decisions can be just as mysterious. Our right-engine start requestor didn’t realize just how powerful the intake vacuum of a large jet engine could be. Yes, a jacket held loosely by a passenger can end up in the opposite intake and yes, even though it is made of pliable leather, that could be enough to destroy the engine.

Play the safety card

If all your attempts to say “no” land on deaf ears, it could very well be time to firmly say “no” is your final answer and you are willing to lose your job over it. Another military truism is “don’t fall on your sword over every issue, but when you do, make sure it counts.” Our duty day wary pilot was fortunate to be in a good job market and may not have made the same decision in tougher times. But when he took his stand he made it clear this was a matter of safety; his fellow pilots took notice. The chief pilot had to realize also that had the pilot been fired he would have made it clear to the company why he was leaving. It would have been a “lose-lose” situation.

The best way to avoid these situations in the first place is to establish a no-nonsense reputation that makes it clear to your passengers that you will not compromise your integrity or their safety. If you are in an unfortunate environment where that hasn’t been done, it is never too late to begin again.

6

Case study: the clean slate

Eddie was unhappy to see his name on the schedule for a trip to Hilton Head Island Airport (KHXD) in South Carolina. He knew the company’s CEO was an avid golfer and he knew that the rest of his flight department quietly agreed to start operations to the 4,300’ runway. Their company rules said their Challenger 604 was restricted from landing with anything less than 5,000’, but the chief pilot had waived that. At first the waiver was heavily considered, required optimal weather and a very senior crew. Now, Eddie realized, any crew could be assigned the dreaded trip.

“I can’t run a flight department with special rules for certain captains,” the chief pilot said. “Either you can fly every trip or you can’t fly any.” The chief pilot reluctantly took Eddie off the trip and was greeted with a sea of complaints from the other pilots. As it turned out, every line pilot thought the runway was too short. “What am I supposed to do?” the chief pilot wondered.

Coincidently, the flight department underwent an independent safety audit and was presented with a very complimentary draft report. “I didn’t write you up for this,” the auditor said behind closed doors to the chief pilot, “but your guys are really unhappy about the Hilton Head situation. I really can’t blame them; that runway is too short for a Challenger. You might consider going to Savannah instead.”

“Could you write us up, please?” the chief pilot said. “You would be doing us a favor.”

The auditor immediately recognized the chief pilot’s plan and agreed. The flight department started flying to Savannah International Airport (KSAV) for the CEO’s golf trips. “We are always looking to improve,” the chief pilot told the CEO. “Our recent safety audit revealed we are operating at the highest levels of safety with one exception and we agreed to tackle that exception head on. The risks associated with landing on such a short runway are too high.” The CEO only shrugged and said, “Okay. I just want to be safe.”

Sometimes all it takes is for one person to make the right decision to inspire others to follow suit . . .

James,

So one busy afternoon at Teterboro there was a fast moving front coming in from the southwest. Strong winds, hard rain, stronger winds and turbulence and lots of dark clouds and blue sky at the same time. Planes were landing crooked and instantly weathervaning into the wind on takeoff. I asked ground control for some pilot reports. They were not encouraging.

Yet everyone was operating as if there was no weather. Looking at my radar apps I could see that the bulk of the storm would pass in 30-40 minutes or so. You have to understand that our boss is a time hound, meaning he HATES losing time. That pressure is constant for us until we ignore it.

I decided to tell the ground controller that “we’re ready to taxi, but would like to wait in the holding area close to the runway until the weather conditions get better”. We received our taxi instructions and parked in the waiting area.

I was hoping I would not be quietly criticized by my fellow aviators as I suspected. But I announced my intentions publicly on purpose because I couldn’t understand why everyone was ignoring the harsh weather. Especially after the on air pilot reports. Next thing I knew, I began to hear other pilots asking about pilot reports in more detail.

Then I heard some interesting requests. At least 5 other pilots said they were ready for taxi but wanted to delay their takeoff. They lined up next to us confirming several things.

1. I wasn’t the only one not comfortable taking off in those conditions

2. If one person announces why they are waiting to depart or land, then it breaks the chain. Others either say to themselves “what does he know that I don’t?” Or, glad he said that. It makes it easier for me to do the same....

Never stop thinking.