In one of my Air Force squadrons a favorite reply to any unusual request was, simply, “We can do that!” It was the height of bravado and team spirit and was looked upon favorably by fellow crewmembers and by the chain of command. My introduction to this elan was in my Boeing 707 (EC-135) squadron in Hawaii and I was one of its greatest practitioners. But in the years I had flying that airplane I slowly began to understand that sometimes the better thought would have been, “Should we do that?”

— James Albright

Updated:

2020-12-05

The height of my zeal for the method was with a load of passengers waiting to fly from Hawaii to California. One of our electrical generators was broken and our home base was fresh out of spares. We had one generator on each of three of the four engines, and they were prone to failing. The rule book said we needed to have them all to cross the pond with one exception. We could fly the airplane to the “first point of repair.” Since our mainland destination had the part, I elected to fly a few thousand miles overwater with one less generator. The passengers thought I was a genius and I got an “Atta Boy!” commendation. The squadron was evenly divided; some said I deserved a pat on the back, others said I needed a kick in the pants. The squadron patted me on the back while half my peers shook their heads in disbelief. I thought the entire episode was just more proof of my “We Can Do That!” bona fides.

I didn’t give the idea much thought until years later, flying for the prestigious 89th Airlift Wing at Andrews Air Force Base. We prided ourselves in the “We Can Do That!” credo and practitioners would often brag about their latest exploits. Our Gulfstream III squadron usually flew members of the President’s cabinet, his wife, top level senators, and an occasional “special mission.” One such mission was to fly a peace treaty – yes, a piece of paper – from Washington, D.C. to Geneva, Switzerland. Since there were no passengers, the crew was allowed to depart a day early so that their valued cargo was sure to be at the site of the ceremony on time. They stopped at Gander, Newfoundland for fuel, making an approach in heavy snow but landing on schedule and getting a full load of fuel for the final leg east. When taxiing out the flaps refused to move beyond 7-1/2 degrees. The GIII’s flap system includes a mechanical link to the horizontal stabilizer which has two positions: takeoff/approach and cruise. The stabilizer was clearly iced up in the cruise position and taxiing back to get the tail de-iced would have cost the crew 30 minutes. The minimum flap setting for takeoff was 10 degrees and there were no procedures for a frozen stabilizer other than to land as soon as possible. The crew elected to takeoff, reasoning that their performance would be adequate and that the ice on the tail would sublimate once above the clouds.

As it turns out the crew was right: they got off the runway with room to spare, and the ice did sublimate, three hours later. The pilots took turns pushing the yoke forward since the horizontal stabilizer was so grossly out of trim that the push force was outside the autopilot’s capability. News of the crew’s “We Can Do That!” episode beat them home to the squadron, where the pilot force was evenly divided about their judgment. One-half wanted the pilot’s awarded, the other half wanted them fired. I was in the latter category. They didn’t have any performance data indicating they could takeoff with 7-1/2 degrees of flap, the practice was not allowed in our manuals, and flying out of trim for three hours was putting stresses on the aircraft that had never been tested. In the end, the crew got a pat on the back and the episode was never again mentioned. (Until now, of course.)

So, as it turns out, it took about five years to cure me of the “We Can Do That!” spirit. I am thankful that nobody got hurt and that I never bent any metal in the process of getting my mind right. How could have I been so blind for so long? As it turns out, we pilots are highly susceptible to this mental handicap. We can look at a few examples as a way of inoculating ourselves.

1 — “Captain, can you takeoff with just one engine?”

2 — “Captain, would you like some fuel system icing inhibitor?”

1

“Captain, can you takeoff with just one engine?”

I’ve spent most of my career flying twin-engine jets, almost always with both engines operating. With just a few exceptions, my single-engine experience has been limited to sitting in the chocks, wondering why one or the other engine failed to start. My “We Can Do That!” attitude in these situations is usually directed to a mechanic, looking for a spare igniter or air turbine starter. I’ve had passengers ask if we can fly with just one engine and I explained the manufacturer assures me that I can takeoff with just one engine, provided I had both for most of the takeoff roll. I’ve never considered beginning the takeoff with just one engine turning. But that’s just me.

On March 19, 1998, the pilot of Aérospatiale SN-601 Corvette N600RA was faced with his “We Can Do That!” moment at Portland International Airport, Oregon (KPDX). He was the director of operations for his company, a Part 135 commercial operator. The trip was to be flown under Part 91, with three passengers. While the Corvette required two pilots, he was the only multi-engine pilot on board. He put one of the passengers, a single-engine rated private pilot, in the copilot’s seat. While taxiing out for takeoff, he was unable to start the right engine. He returned to the fixed base operator but declined any kind of maintenance help and instead made a few phone calls. He canceled his Instrument Flight Rules flight plan and refiled under Visual Flight Rules to Redmond, Oregon.

The pilot and passengers then reboarded, restarted the left engine, and taxied back to the runway. Witnesses say the “airplane seemed to be going much more slowly than usual at rotation, and seemed much quieter than usual during the takeoff attempt.” The airplane became airborne about 4,000 feet down the runway, its wings rocking, and achieved a maximum altitude of 5 to 10 feet before settling back to the ground where it slid off the side of the runway. The aircraft was damaged beyond repair but none of the occupants were harmed.

In a written statement to the FAA investigator, the pilot said the right engine failed just as he started to rotate. Examination of the Cockpit Voice Recorder revealed that the engine was never started in the first place and the pilot was attempting a “compression” start by getting airflow into the engine during the takeoff roll. Of course, there is no such procedure in the Corvette’s Airplane Flight Manual (AFM) which specified the minimum speed for an air start would have been 200 knots.

We will never know the pilot’s motivations, but I hypothesize he was trying to ferry the airplane to home base where he might have had a starter on the shelf. His attempt to save a few dollars in parts cost him the airplane.

More about this: Case Study: Aérospatiale SN-601 Corvette N600RA.

For another example of "We Can Do That!" single-engine stupidity: Careless and Reckless / No Comment Necessary.

2

“Captain, would you like some fuel system icing inhibitor?”

I get the question now and then when ordering fuel: “With or without?” Some jets require a Fuel System Icing Inhibitor (FSII) be added to the fuel. I am fortunate in that my aircraft has built-in provisions to heat engine fuel, but I do have to keep an eye on it on cold days or at high altitudes. So my answer is almost always no, but I do consider it. Many fuel trucks can automatically dispense it, or you can add it manually. The last time I checked, a can of FSII will cost about $20 and will be sufficient to treat about 150 gallons of fuel. While it isn’t free, it seems pretty reasonable if it keeps your engines turning when the outside air temperature gets cold.

On March 22, 2009, a veteran Pilatus PC-12 pilot flew multiple legs from Redlands Municipal Airport, California (KREI) destined for Gallatin Field, Bozeman, Montana (KBZN). On the accident flight, the aircraft was loaded with 13 passengers, 4 more than authorized by the Pilatus AFM. The weather was good, but it was cold. The pilot did not request or was seen to have added any type of fuel system icing inhibitor at his point of origin or any of the fuel stops along the way. The PC-12 AFM requires FSII be used for temperatures below 0°C. Because standard temperature at 7,500 feet is O°C and each of the aircraft’s cruise altitudes that day were above that altitude, an FSII would have been required for each leg.

The Pilatus PC-12 has two fuel tanks, one in each wing, that feed the engine simultaneously. Each tank has a boost pump which automatically activates whenever the fuel pressure drops or in response to a fuel imbalance. Fuel in excess of the engine’s requirements are sent back to both tanks.

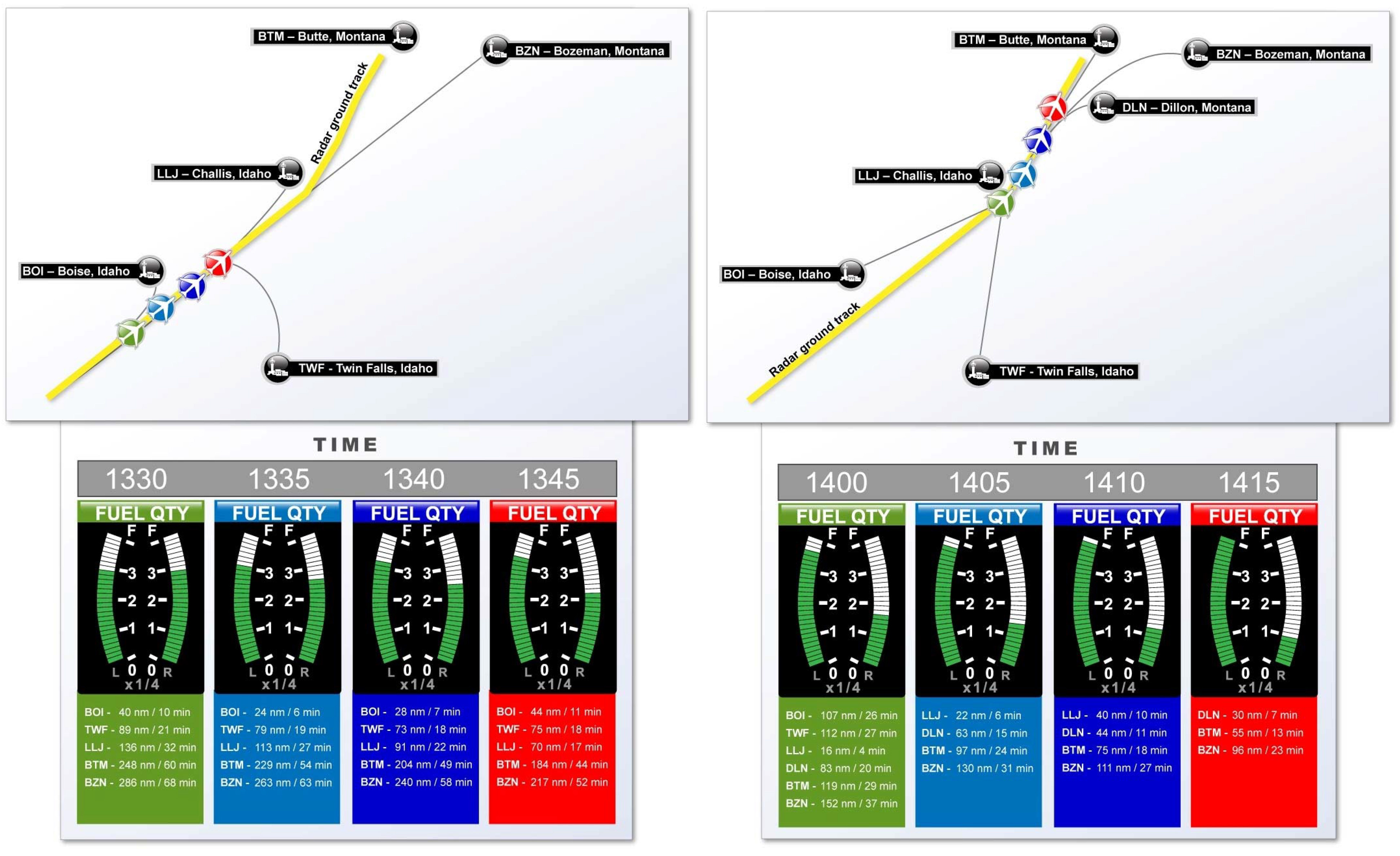

About 1 hour 13 minutes into the final flight, both fuel pumps began cycling because of low fuel pressure, evidently because of fuel icing in both tanks. The right tank managed to deliver more fuel than the left, creating a fuel imbalance. Five minutes later, the right pump ran continuously to correct the fuel imbalance. Three minutes later, fuel was being drawn solely from the right fuel tank. Because the right tank was delivering more fuel to the engine than it needed, excess fuel was returned to both tanks. The right tank was in effect feeding the left tank.

The fuel imbalance exceeded aircraft limitations about 1 hour after takeoff and the AFM stated that the pilot should land the airplane as soon as practical in this situation. He instead passed several viable airports, still heading for his planned destination. It wasn’t until 30 minutes later he decided to divert, but he did not select the nearest viable airport. He instead chose Bert Mooney Airport, Butte, Montana (KBTM), presumably a more convenient option for his passengers. The aircraft remained controllable until the last minutes of the flight, but the pilot lost control while maneuvering to land. The aircraft impacted the ground short of the runway and everyone on board was killed.

We will never know why the pilot failed to add fuel system icing inhibitor, but we can surmise he bypassed several viable airports wanting to get his passengers to their intended destination.

More about this: Case Study: Pilatus PC-12 N128CM.

3

“Captain, can you fly another three hours?”

I’ve flown for a few outfits that schedule trips to the duty limits of the crew, bargaining that the winds will be favorable, the passengers show up on time, and that every airport turn goes like clockwork. Because it is scheduled legally, the “unforeseen” complications are allowed and the crew goes to bed a few hours late. In good organizations, we are usually able to push back and get things changed for the better. In bad organizations, more often than not, we are shown the door when we push back too much. The stories are sadly too common. Here is one of many.

In 2017 a Hong Kong-based operator scheduled a Bombardier Global Express 5000 to fly from Las Vegas, Nevada to Jeju, South Korea with a fuel stop in Anchorage, Alaska. The duty day came in at 18.3 hours, 20 minutes beyond their 3-pilot duty day limit of 18 hours. The three pilots included two captains and a first officer. One of the captains refused the trip and was replaced with another captain willing to violate the limit. A Nevada sandstorm delayed their departure and they made it to Jeju Island after logging more than 20 hours of duty time. The lead passenger asked to continue on to Beijing, China. Of course, the pilots agreed, extending their day another three hours.

The captain who refused the trip was summarily fired from the company. He sued the company, who settled out of court. In the end he received 3 months of back pay but little else. It took him two years to find another job. The Hong Kong aviation authorities said there was nothing to be done about it, since it was a non-commercial operation.

The worst incident I can recall was the 2013 wrong airport landing of a C-17 cargo plane. It should have landed at MacDill Air Force Base but ended up on the 3,405 ft. runway at the nearby Peter O’Knight Airport on Davis Island, Florida. The pilots had been pushed to their limits in the days leading up to the 12-hour flight from Italy back to the United States. The Air Force accident report says the crew “flew into complex airfields, dealt with multiple mission changes and flew long mission legs with several stops each day.” The flight was originally bound for Kabul, Afghanistan but then changed to Andrews Air Force Base, Maryland, and then to MacDill Air Force Base about an hour before takeoff. While the crew had the opportunity to sleep eight hours the night before the long flight, time zone changes prevented them from “getting a good night’s rest.” Air Force regulations not only enable aircraft commanders to terminate missions due to fatigue factors, they require them to do so. But this rarely happens because Air Force pilots, like most pilots, “Can Do!” I am told that the general officer passenger stressed that getting back to MacDill was a matter of national security. Everyone on board was fortunate to have walked away unscathed.

These stories do not always end this way. About twenty years ago, TAG Aviation USA routinely lost business by refusing to violate its own duty day rules, even when pushed by wealthy clients. In one such episode, a crew was returning to California from the Middle East via a fuel stop and crew change in Narsarsuaq, Greenland (BGBW). The weather was below minimums and the inbound crew diverted to Kangerlussuaq, Greenland (BGSF), more than 400 miles to the north. The passenger insisted the original crew press on to California and the crew agreed. TAG Aviation USA forbade the takeoff and made it clear to the pilots that they could not violate their duty limits. The client had to spend the night in Greenland; he fired TAG Aviation USA the next day. To its credit, TAG found the pilots new (and better) jobs. Of course, TAG Aviation USA is no more, and management companies with this kind of backbone are rare. It is up to us, as pilots, to have the spines our companies may lack.

4

Change “We” to “I” and “can” to “cannot”

Sometimes the “We Can Do That!” syndrome is easily defeated. As the aircraft commander flying a White House trip, I was once ordered by the senior diplomat to divert from Mogadishu, Somalia to a nearby grass strip. Flying a Gulfstream III, it was an easy order to refuse.

Sometimes, as a military pilot, the order cannot be refused. I flew my Air Force Gulfstreams into Sarajevo, Bosnia, many times in 1996 when the airport was bordered by surface-to-air missiles and anti-aircraft artillery. We often saw muzzle flashes from the ground and twice the aircraft following us were hit. But the rules as a military aviator are different. As civilians, we are empowered with the word “no.”

And yet the temptation to say, “We can do that!” is often too great to use the “no” word. Like the 29-year old me flying with one less generator, we want to develop “can do” reputations. Like my squadron mate flying a piece of paper with an iced-up tail, we want to avoid being associated with mission delay. I believe in these two examples we can find the problem: we pilots take all of this personally. We need to stop doing that.

The first problem with “We can do that!” is the word “we.” That removes responsibility from us as individuals and enables us to push our limits in furtherance of the greater good. The collective “we” wants us to takeoff with less than an airworthy airplane, so who are “we” to refuse that? If “we” are willing to fly 23 hours to China, that means others have made the decision to do that, why can’t you?

Try rephrasing the answer, “I can do that!” and see if it changes your confidence in the agreed upon course of action. And then envision your name printed in a National Transportation Safety Board report, listing your name, training records, and immediate history just prior to an accident. Think of your family reading news reports about a fatigue-impacted decision you made late at night that resulted in something much worse than a wrong-airport landing. Then consider if “I can do that!” should really be “I cannot do that.”