After ten years it is time to retire my trusty Gulfstream G450 in trade for a brand new Gulfstream GVII-G500, or simply a "Gee Seven" or "Gee Five Hundred." We take delivery in a few months.

— James Albright

Updated:

2019-07-10

I am typing this aboard an airline flight from Savannah heading home. Yesterday I passed my G500 initial check ride, earning my ninth (and final) type rating. The minute I first laid eyes on the airplane I knew it was something special. As I started to learn more and more about it, I knew it was the right answer to our company's quest for a newer airplane. I signed the paperwork to buy it a year and a half ago. Now that I finally have the training under my belt, I am looking forward to it more than ever.

Of course that means an entirely new section for Code7700.com. But this one will be a bit different. As of this writing, there are fewer than 20 of these airplanes in the hands of the flying public. I attended only the tenth initial class. So much of what appears here is brand new and will be aimed at getting pilots up to speed. (To do that, I need to get up to speed!) Since we are so new here, I want to bring together a group of like minded pilots. More on that below.

A Gulfstream GVII (G500)

First, A Word About Gulfstream Ones and Twos and . . . — The numbering system can be confusing, but can reveal a few secrets about each airplane in the series. There never really was a "Gee One" until there was a "Gee Two" but even that airplane and the "Gee Three" were never enshrined officially until there was a "Gee Four." Here are the official type ratings as they still appear on a pilot's license: G-159, G-1159, G-IV, G-V, GVI, and GVII. Even that missing "dash" has a story to tell.

Second, we need to recognize when Evolution Meets Revolution — Gulfstream has always operated on the philosophy of "if it isn't broke, keep it but improve it." There are parts of the G-159 in the GVI. We are told the GVII is a "clean sheet airplane" and that is mostly true. But you will find parts of the G-V and GVI in the GVII. But much of the GVII came right out of Gulfstream's own drawing board. If the existing technology wasn't up to the task, Gulfstream invented new technology.

Third, if you are going to be a GVII pilot, you may find Bending the Learning Curve can save you considerable effort during training and your continued efforts to master the airplane. Of course I am brand new here too, so I will be relying on your inputs as well as my research and experience.

Fourth, if you are on the fence about this aircraft, you might like to peruse my Wish List of airplane innovations that have been granted in the GVII.

A Word About Gulfstream Ones and Twos and . . .

If you are unfamiliar with the Gulfstream story, perhaps a quick review is in order. This is the lineage from the original Gulfstream to the present day GVII. I am not including the G-100, G-150, G-200, G-250 now G-280 models as they came from outside this line.

The Grumman "Gulfstream" (Type: G-159)

The Grumman company was in the business of making military aircraft and realized a need for a fast and roomy business aircraft and came up with what they called "The Gulfstream" in 1958. The type certificate was for a G-159. The aircraft were built in Bethpage, New York. I believe they built 200 of them.

The Grumman "Gulfstream II" (Type: G-1159)

In 1966, the Grumman followed its earlier design by keeping the basic fuselage, strapping on two Rolls-Royce jet engines, a swept wing, and a T-tail. They called this the "Gulfstream II" with the type designation of G-1159. They opened a plant in Savannah, Georgia to build the aircraft, of which they made 256.

The Gulfstream American "Gulfstream III" (Type: G-1159)

Air Force C-20A 30500, a Gulfstream III, (Matt Birch photo, http://visualapproachimages.com)

In 1973 the company was renamed Gulfstream American and in 1980 they delivered their first Gulfstream III. The aircraft had about 6 feet more wing span and added winglets. It shared the G-1159 type certificate of the earlier aircraft. 202 were built.

The Gulfstream Aerospace Corporation "Gulfstream IV" (Type: G-IV)

In 1982 the company became the Gulfstream Aerospace Corporation and in 1987 they certified a new airplane called the Gulfstream IV and typed the G-IV. Well over 500 have been built. Designations got a little messy with G300 and G400 variants, based on shorter range. There was also the G-IVSP with several improvements.

The Gulfstream Aerospace "Gulfstream V" (Type: G-V)

Gulfstream Aerospace reinvented the market with a new category of business jets: ultra long range. The G-V was certified in 1997 and had a range of 6,500 nm. They built 193 of them, which may not sound like a successful run, but it gave birth to something even better . . .

The Gulfstream Aerospace "Gulfstream G550" (Type: G-V)

In 2003 Gulfstream gave the airplane new avionics and various systems improvements to increase the already long range and improve the already high performance. To date, they've produced nearly 500 and there is no sign the production will come to an end. (There is still no airplane that can touch its mix of low speed, short field capability with long range, high altitude and high speed performance.) As with the earlier G-IV, things got messy with shorter range G500 variants, which made things interesting later on.

The Gulfstream Aerospace "Gulfstream G450" (Type: G-V)

In 2004 Gulfstream blended elements of the G-IV, the G-V, and the G-550 to come up with the G-450. It was a vastly improved G-IV but not much else. 365 were built. Here again things got messy with a G-350 variant. Notice that the G-V, G-550, and G-450 all share the same G-V type rating.

The Gulfstream Aerospace "Gulfstream G650" (Type: GVI)

G-650 VP-CER, (Matt Birch photo, http://visualapproachimages.com)

In 2008 Gulfstream came out with its largest ever model, called the G650 but typed the GVI. Gulfstream departed from the tried and true G-159 fuselage diameter for the first time and gave the G650 a wider cabin. The aircraft is significantly faster than earlier models and employs fly-by-wire technology. Note the missing dash ("-") from the type.

The Gulfstream Aerospace "Gulfstream G500" (Type: GVII)

G500 N507GD, (Matt Birch photo, http://visualapproachimages.com)

In 2018 Gulfstream certified the GVII-500, to be followed the next year with the GVII-600. The 600 is a bit longer, has a wider wing span, goes further, and has a bit more thrust. Other than that, they are identical. Pilots who have flown both say the only way you can tell which you are flying is to look at a fuel gauge.

Evolution Meets Revolution

I have often been asked by our company what I thought about the most recent offerings from various manufacturers and I am usually able to offer an opinion of sorts. When I was asked about the G500 I didn't have an opinion because I didn't know. "You should learn about it," I was told. So I flew down to Savannah to tour the factory and spend several hours with a few members of the Gulfstream design team. I came home and told our CEO that every Gulfstream before this one was simply an evolutionary step from the G159 and represented only marginal improvements. But this airplane, the G500, was a revolutionary change. This was going to be something special. And it has turned out to be just that. Why? The list is pretty long but on the top of that list are electrical power control, avionics, aerodynamics, thrust production, and philosophy. An eclectic list, I admit . . .

Electrical power control

You may have heard about airplanes that have eliminated most of their physical circuit breakers with what can be called "virtual circuit breakers" that do not occupy panel space, are less prone to failure, and reduce the weight of the airplane. In many airplanes, I suppose, that is all they do. See Circuit Breakers for a discussion about physical versus virtual circuit breakers.

A virtual circuit breaker gives you much more capability if you really take advantage of it. There are many mundane cockpit chores that are repetitious and time consuming, which means they are apt to be done incorrectly or skipped entirely. Thinking of that virtual circuit breaker as a virtual switch will broaden the possibility of what it can do. Starting the APU on an older model of Gulfstream, for example, requires multiple steps: (1) turning it on, (2) doing a fire protection system check, (3) turning on a fuel boost pump, (4) turning on the airplane's beacon light, (5) activating a starter, (6) monitoring the start, and (7) activating bleed air and electrical system outputs. Of those, only steps 1, 2, and 5 really require a pilot. So leave the rest of those chores to the computers.

Removing all those pesky circuit breakers and switches from the cockpit leaves you with fewer things to break and more cockpit real estate for . . .

Avionics

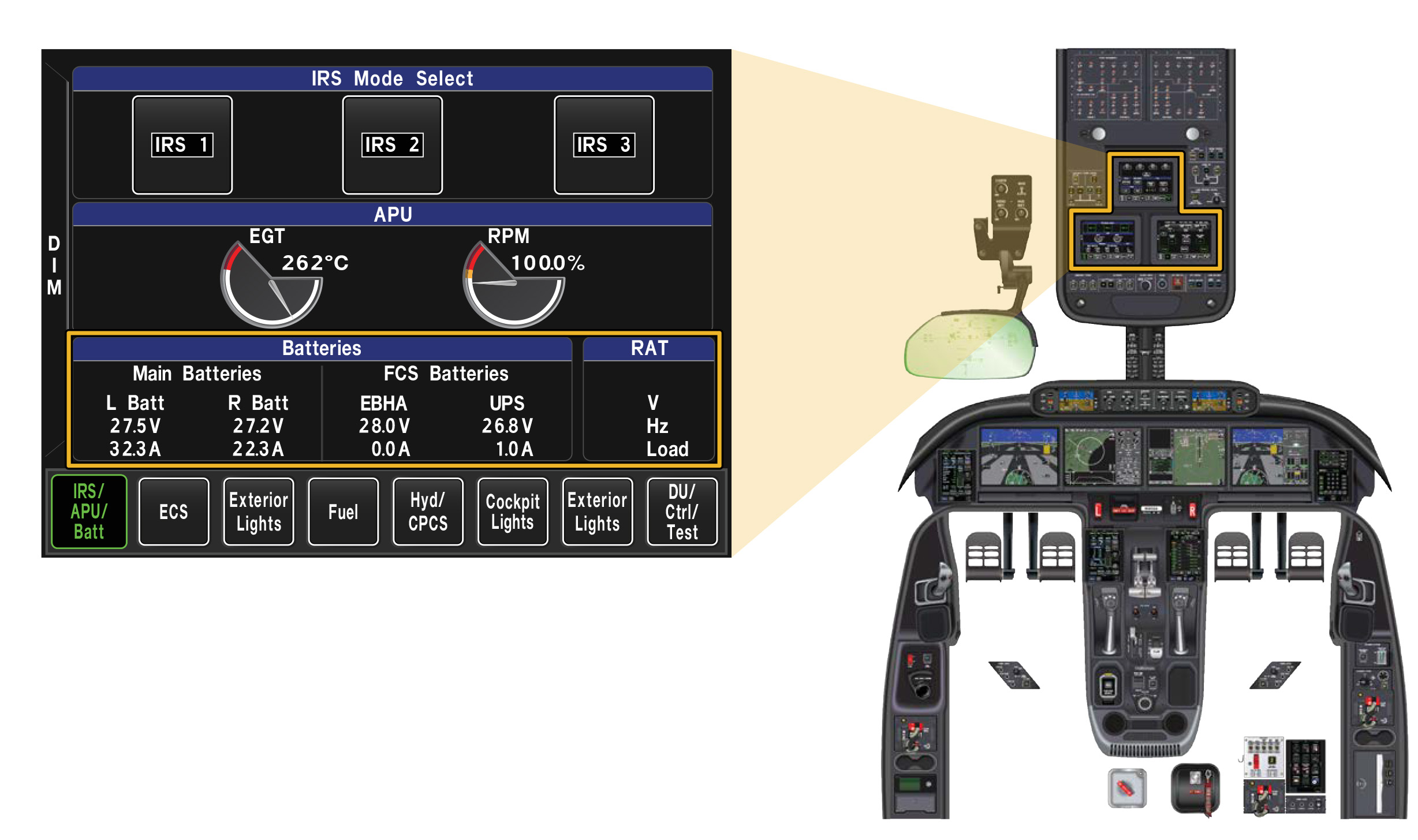

Cockpits have been trending towards more and more glass over the years but still we have hardware switches and other controls which are prone to breaking and take up real estate. Take, for example, the need to have switches to activate your Inertial Reference Units and lights to tell you their status. Once you've turned them on, those switches and lights become wasted real estate. In the G500 you don't touch them because they come on automatically after the APU is started. But you still need switches and indicators. So what to do?

There are three Overhead Panel Touchscreens (OHPTS) that are identical and allow you to access just about every system on the airplane on an "as needed" basis. Each screen has complete access so you can display three different pages at the same time and you can dispatch with a screen inoperative. You can imagine that being able to shut off a fuel boost pump or an air conditioning pack with a touch of a finger might be problematic if your finger hits the wrong area of the screen. Each OHPTS is bordered by a physical edge you can brace your fingers or thumb on so as to be more precise, even in turbulence. Critical switches are guarded, in a sense, by giving you "Accept" and "Cancel" options. These panel buttons require a physical press, not just a momentary touch.

Another advantage to this approach is that when things go wrong, you can draw the pilot's attention to where it needs to go. Those buttons on the bottom will light up in amber or cyan as needed. Let's say you have a fuel imbalance that generates an amber CAS message. The "Fuel" button will light up in amber, telling you that is the page you need.

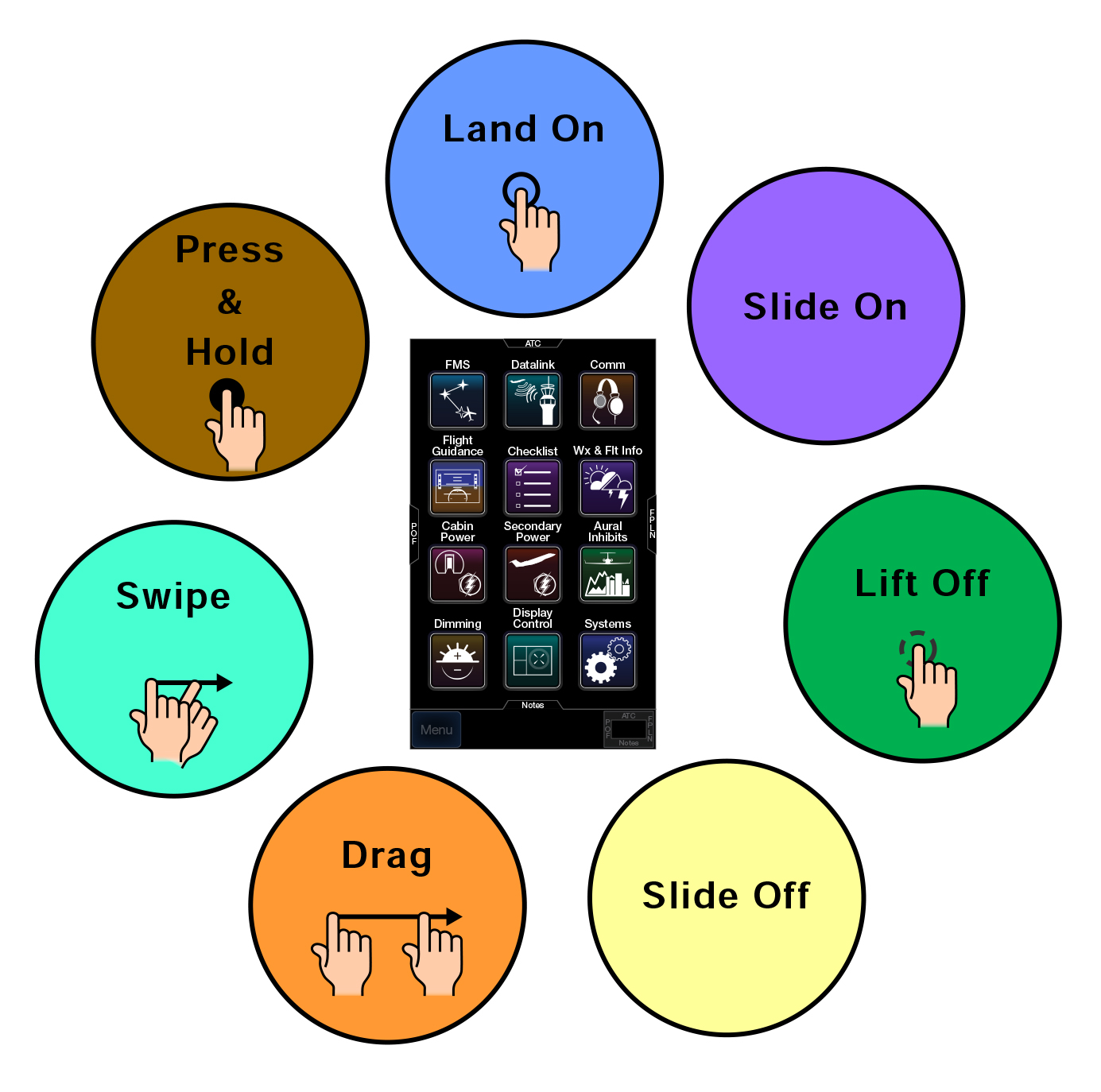

G500 Touch Screen Controller gestures, PAS, p. 2-7

This philosophy is continued with five more panels called Touch Screen Controllers (TSCs), each about the size of a small iPad. Here you control everything from that power distribution system to datalink. Your cockpit map light control resides in here as does your Flight Management System (FMS). While there are menus you can dive into, as you would be required to do with a conventional FMS, you can get to where you need to go with various motions that will be familiar to most iPhone users.

While there is a learning curve, once you adapt, everything is easier to access and control.

Thrust production

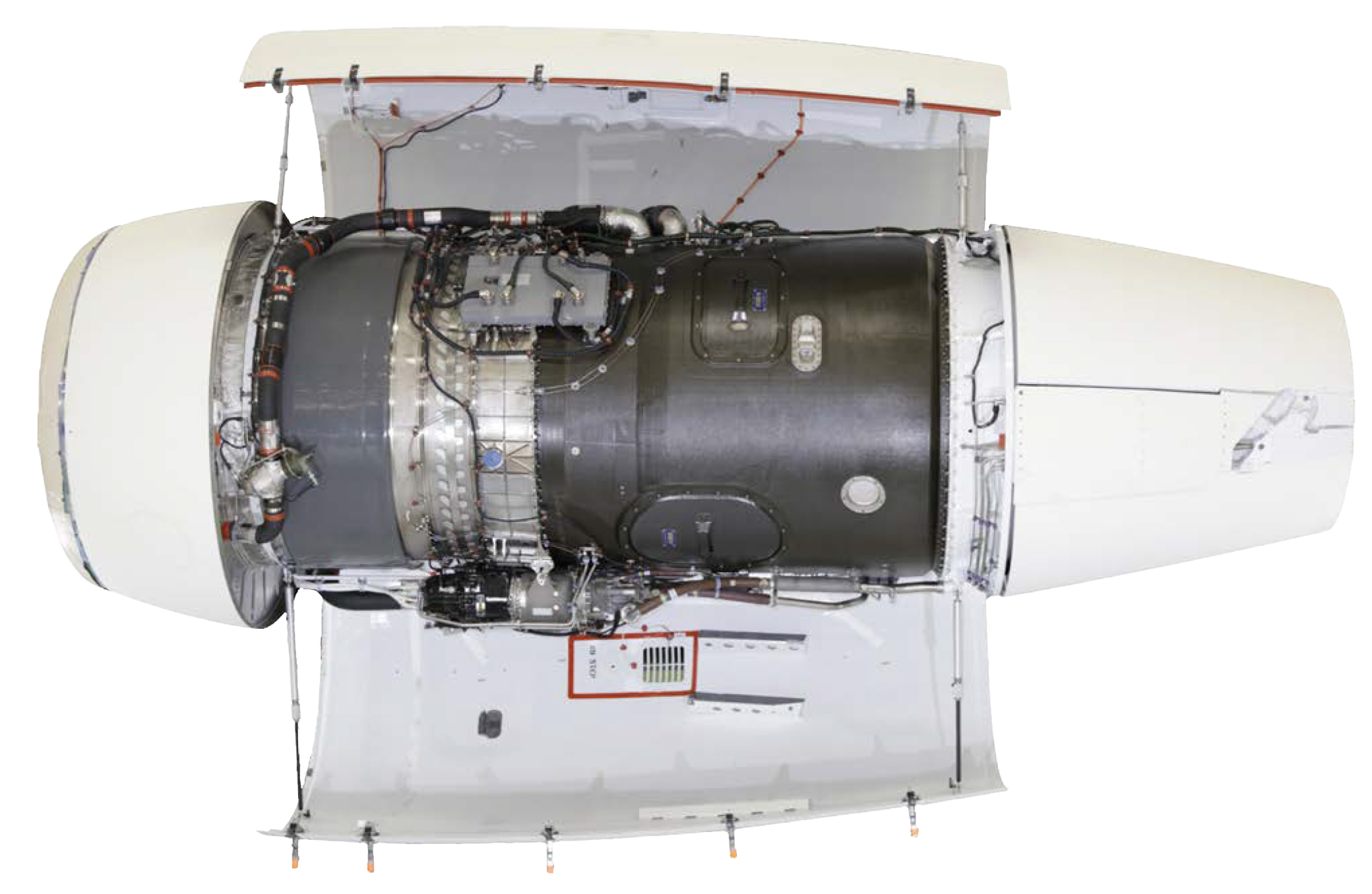

G500 Powerplant, PAS, p. 14-1.

The first time I saw a G500 with its engine cowls open it was on the production floor and I thought they hadn't yet completed installing it. Gone were all the accessories, pipes, wiring, and other complicated gizmos found on the Rolls-Royce engines used on every other Gulfstream I had ever flown. It is very clean. But that isn't the news here.

Of course the airplane continues to set speed and fuel economy records because, in part, of these Pratt & Whitney PW814GA engines. As you will see below, these engines push the airplane much faster with less gas. But that isn't the news here.

The news here is the FADEC. Gulfstream aircraft have been using Full Authority Digital Electronic Control (FADEC) for their engines since the GV. The news is that this particular FADEC is smarter than all those it follows. Engine start is a two step process: select the fuel control to "Run" and press a button called "Start." You are now a spectator. GV, G550, and G550 pilots understand there are times a bow of the engine core's shafts will require an amount of rotation to smooth things out. This FADEC memorizes the exact time needed and takes care of that for you. Previous FADECs didn't quite comprehend the different procedures needed for high elevation airports. This one does. Hot start? This FADEC will drastically reduce fuel flow to "save" the start if it can, abort it if it can't. We've ended up with more thrust with less weight and effort. And that allows us to capitalize on . . .

Aerodynamics

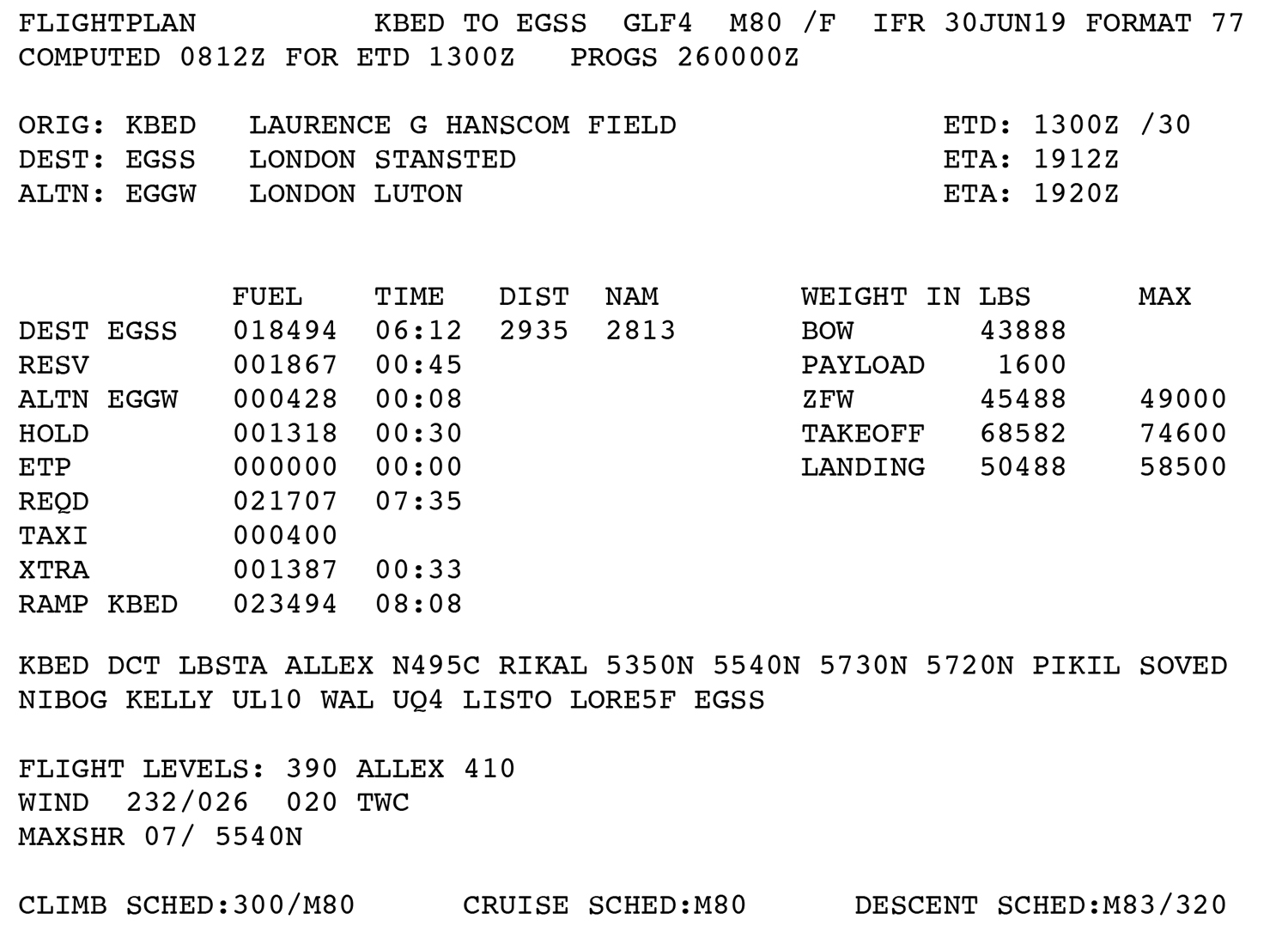

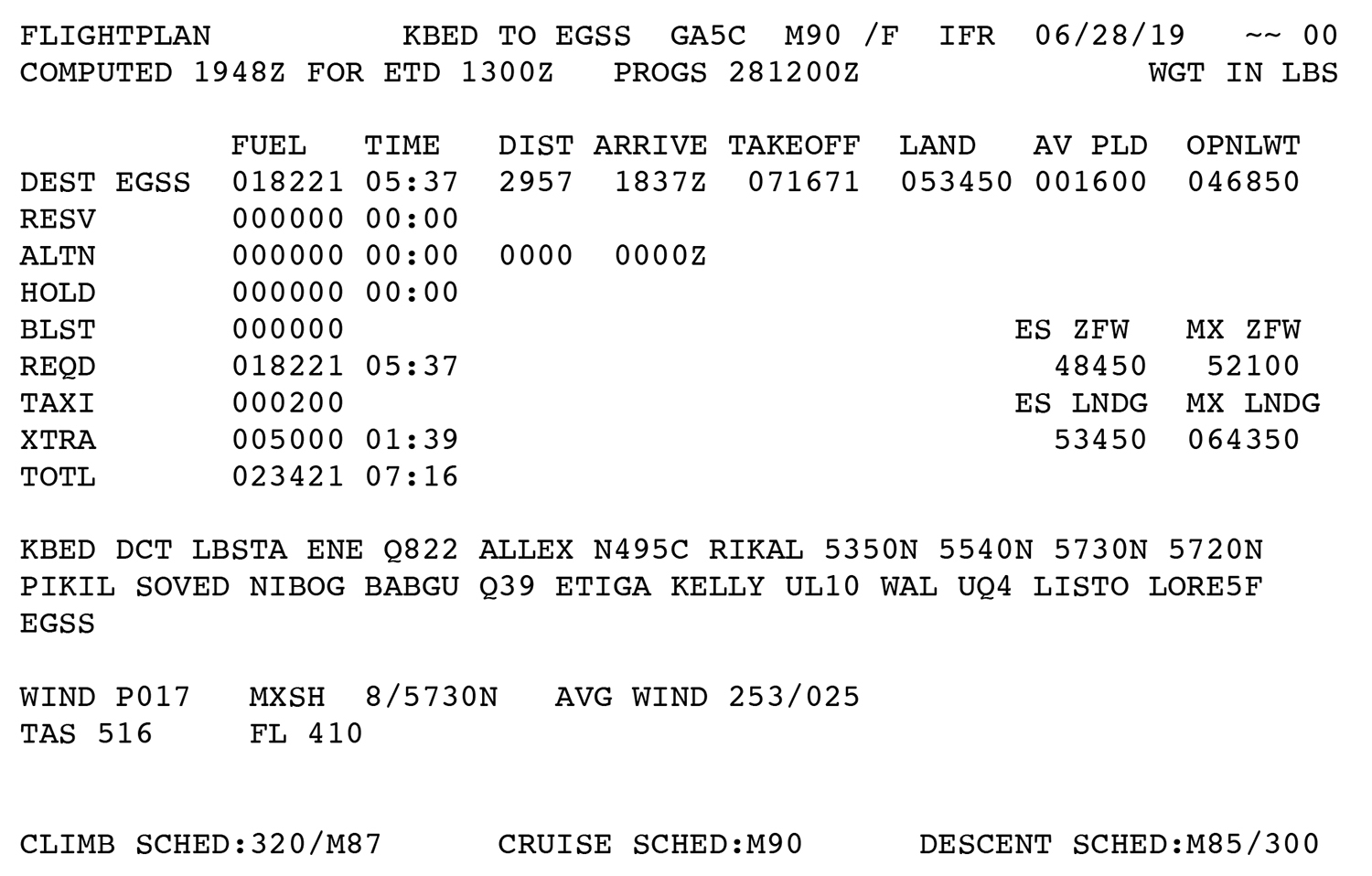

One look at the wings will tell you all you need to know about the aerodynamics but perhaps a comparison of performance will tell you more. The G500 is just a little larger than the G450, so let's compare them on a trip. We fly from Hanscom Field, Bedford, Massachusetts (KBED) to many of the airports in the London area, including Stansted, England (EGSS). The first flight plan extract here is a filed flight plan in our G450. The second is another flight plan with conditions made to match in a G500. Note that we could easily fly both aircraft higher, but we choose FL 410 to keep us from having to wear oxygen above that altitude. Allowing both aircraft to fly at optimal altitudes will make these results even more striking.

Sample flight plan from KBED to EGSS in a Gulfstream G450. (The flight plan code is GLF4, since the performance is similar to the GIV.)

Flying at the G450's normal cruise speed (M0.80) gets us to London in 6 hours 12 minutes and requires 18,494 lbs. of fuel. Oh yes, the cabin altitude will be around 6,000 feet.

Sample flight plan from KBED to EGSS in a Gulfstream GVII-G500. (The flight plan code is GA5C, "GA" meaning Gulfstream Aerospace, "5" for 500, and "C" for one-hundred.)

Flying at the G500's normal cruise speed (M0.90) gets us to London in 5 hours 37 minutes (35 minutes faster) and requires 18,221 lbs. of fuel (a couple of hundred pounds less). The cabin altitude will be just over 3,000 feet.

So you get to where you want to go faster, burn less gas, and will feel better when you arrive.

Philosophy

Yes: philosophy. You will hear that this is a "fly by CAS" airplane because the Crew Alerting System (CAS) has become very smart. With previous aircraft the CAS simply reported problems as they occurred and only discriminated by putting the really bad stuff (red CAS messages) on top, the pretty bad stuff (amber CAS messages) next, followed by all the others (cyan and white). Gulfstream has reinvented the idea of CAS with new types of messages and ways to filter them. In other aircraft having the CAS panel light up seconds before V1 meant you had to glance at the stack of red, amber, and cyan messages and make a decision. With this new CAS system, if you here a triple or double chime before V1 you abort. Otherwise, you press on.

But the philosophy change continues. Aircraft systems and procedures are built around the pilot. Things that don't require pilot input are done automatically, but the pilot has the ability to intervene. Things that will require pilot involvement are presented in more intuitive ways. Normal and abnormal checklists are dramatically reduced in size. It is almost as if the aircraft designers were keeping a running wish list from decades of Gulfstream pilot experiences and checking those off, one by one.

So all of this sounds pretty good, right? Any drawbacks? There is one, I suppose. The learning curve is pretty steep. As I write this, I just finished GVII Initial Training and have added my ninth type rating. I was paired with a Gulfstream G650 production test pilot who was very sharp. But he and I had to work pretty hard. In the end the check ride was easy for us, but getting to the check ride took a lot of work. FlightSafety's GVII initial is innovative and very good. But they could have done a better job of steering our efforts to maximize our study efforts. If you are heading to GVII initial I am sure the program will be better. We attended class number ten and were told the course had improved since class number nine. I am sure class number eleven is getting a better program than we did. This is the nature of flying something this new. But no matter your class number, perhaps I can help you with your learning curve . . .

Bending the Learning Curve

You will see a lot of "work in progress" on these G500 pages, I have a lot of content but most of it is cut and pastes from source documents that needs some editing and reorganizing. I am working on it!

Having just gone through the GVII initial course I see that my traditional order of study (limitations, systems, normals, abnormals, avionics) doesn't work. Not only is the airplane "fly-by-wire," much of the systems are "control-by-wire" and everything relates to everything else. It is a holistic airplane.

The check ride was pretty easy but I had an advantage. First, I got the best instructors, the best time slots, the best schedule. I think FlightSafety knew I was writing about this for this website and for Business & Commercial Aviation magazine, so I was pampered. Second, I was paired with one of the finest production test pilots I've ever known.

Wish List Granted

I mentioned that this particular Gulfstream seems to have answered a long list of wishes from pilots of previous Gulfstreams. It has certainly answered many of mine. Here are some of those wishes answered, a few unanswered, and one or two new wishes.

"I wish it would do this . . . " OR "I wish it didn't do this . . . "

These wishes have been taken care of:

- We seem to do a lot of checking of things that require a lot of switch throwing, light checking, and other mundane procedures that could be done by a computer. Having to do them takes our attention from the more important stuff, tempts us to skip procedures or to get the procedures wrong. For example: the cabin pressure outflow valve check (manual, open, close), the fuel quantity indicator check (press, 700, 700, 1400, two CAS),

- Whenever we set the parking brake we have to hit the aux pump to restore the accumulator. Meanwhile we have two perfectly good hydraulic systems producing 3,000 psi. Why not use it? (This was fixed in the G650.)

- Why are the oxygen panels so easy to mix up, leading to inadvertently dropped masks? Some operators leave the switches on but others worry this will cause leaks. If that is okay, why not guard the switch in the ON position?

- Opening a closed gear door uplock isn't straight forward. Why can't the airplane sort that out for us? (This was sorted out in the G650.)

- There are several valves in the wheel wells that we have to check but the closed and open positions are different. Some are at 11 o'clock, 7 o'clock, and 5 o'clock. Why not label them?

- Why do we have to evaluate temperatures and electrical power status before powering up various electronic displays and other avionics. The airplane should know better than we about when it is okay to turn a display unit on or put power to an navigation system.

- The checklists are too long! The G450 Before Starting Engines checklist takes 76 steps, most of which could be automatic.

- Having a smart list of frequencies for various situations, such as an airport's ground, clearance, and tower frequencies while at that particular airport.

- Needing bleed air pressure for engine start means no air conditioning while the engines are started? Why can't we do both?

- The standby flight displays on many Gulfstreams are in a location too hard to use and why do we have to program it separately from the rest of the avionics? It should already know the correct altimeter setting and the approach particulars.

- It is a bit of a nuisance having to select a different Display Unit (DU) when trying to have a cursor on a different DU. I can't count the number of times I slewed the cursor to the left of DU 3 wanting to click on DU 2, only having to then press the DU 2 button and then move the cursor from its parked position.

- Everybody wants some level of warning inhibits, but it should be better than off or on. These inhibits shouldn't require a button press (on or off) but should be smart enough to know that V1 deserves more inhibition than after the aircraft is clean and climbing.

- In some Gulfstreams having the V-speeds fail to box can require some serious head scratching to figure out what the problem is. Meanwhile your takeoff clearance is ticking away. Why can't the airplane just tell us what the issue is?

- We have all figured out that the bottom message in the highest color CAS stack is the first chronologically in that stack. Most of us have figured out that a lower color CAS might be the problem. Why do we have to read ten or so CAS messages and consider each before knowing what the cause was?

- The ground spoilers on the GII could kill us if they malfunctioned so a lot of hardware was added to make them less prone to failure. Then we added another layer to the weight on wheels system to warn us there was a problem, but not to fix the problem. Why can't the ground spoilers be more bullet proof?

- Previewing an ILS approach doesn't always work the first time and it never works the second time when still inside the same airport area.

- We have been flying down to a DA for a long time and the automatic callouts give us a nice alert that we should either see the landing environment or go around. But the rules are more complicated that that because if we have certain lights in view we can go to 100 feet above the runway in some situations. We should have another layer of automatic callouts.

- Unusual attitude and wind shear recovery in the HUD are next to impossible because the FPV is jumping around too much and the boresight gets lost in all the other symbology.

- Having to extend and retract the spoilers during an emergency descent isn't a big inconvenience, but it is a step we'll miss if we pass out.

- Why do we have to time the oil check when chances are we are going to be busy when the oil check is due? Why can't the computers do that for us?

- I never could figure out the Fire Detection Loop Alert in the GV and later.

- Having to figure out when a rotor bow start is needed and what to do about it is another level of inconvenience. (This was sorted out in the G650.)

"I still wish it would . . ."

These wishes remain:

- It would be very nice to have a QWERTY keyboard available for some TSC entries. Perhaps a Bluetooth version that can be stowed when not in use.

- Why can't the HUD provide an easier display to discern up from down during an engine failure? With the sudden yaw from an engine failure it is a real challenge to keep the wings level in the HUD. You get much better situational awareness from the PFD. Perhaps some synthetic vision in the HUD?

- The V2 to V2+10 "staple" during an engine failure in the HUD is very nice. It would be even nicer in the PFD.

- Why does it take 41,000' feet to take advantage of the Emergency Descent Mode of the autopilot? Why not lower?

- Why isn't the Emergency Descent Mode able to realize when the terrain below is greater than 15,000 feet MSL?

- We have our minimums on the Jeppesen plates, why can't the airplane enter the correct DA and SA for us, allowing us to bump them up if needed?

- My car remembers my seat position and one for my spouse too. With a simple button press we are where we need to be. At the very least, can we have numbered position for seat height, forward placement, and rudder position?

- Those three knobs for the EVS are still too complicated. We shouldn't have to fumble with them all the way down final only to be at the moment of truth with them set incorrectly.

- A camera for each winglet: no more guessing about it clearing an obstacle or not.

- Having a baggage compartment light on the ground service bus so we don't have to fish around for a flashlight.

- How about Bluetooth in the cabin to connect to the audio system?

- It would be nice to have oceanic tracks displayed on DU2 and DU3.

- It would also be nice to be rid of the chore of fuel balancing.

- Being able to come back to the oil system after it has taken a "snapshot" of the oil levels is a great improvement. It would be even better if we could add oil from the cockpit.

"It used to do this, now it doesn't . . ." OR "We never had this capability before, but it could be better . . . "

These are new wishes that didn't exist before:

- Why do the V-speeds disappear at 1,500' AGL? If we are doing a good job flying at V2 to V2+10 we are likely to be focused on just that. At 1,500' we then accelerate to VSE but that speed is gone. In the heat of the moment we might forget it. Why not keep it there until flap retraction?

- Why do the autobrakes have to be set after we've already told the LDG PERF we will be using them?

References

(Source material)

Gulfstream GVII-G500 Airplane Flight Manual, Revision 1, August 31, 2018

Gulfstream GVII-G500 Production Aircraft Systems, Revision 1, Oct 1, 2018

Please note: Gulfstream Aerospace Corporation has no affiliation or connection whatsoever with this website, and Gulfstream does not review, endorse, or approve any of the content included on the site. As a result, Gulfstream is not responsible or liable for your use of any materials or information obtained from this site.

My notebook

My notebook