I first met John Davey in 1985 or so. My logbook shows we flew a trainer from Honolulu to Kona to Maui and back on February 7th of that year. I was an instructor pilot and the commander of Crew Five of the 9th Airborne Command Control Squadron at Hickam Air Force Base and John was a line copilot on Crew Four. Before the year was out we were both elevated to the squadron's senior crew. Before the next year was out I left the squadron for another and John left to become a civilian. He is "Bruce Five" of my oft-told The Tale of Four Bruces. That's because he wasn't actually on the "Bruce Crew," but we thought highly enough of him to give him honorary status. Over the years he was probably the most prolific contributor to my email in box and I never tired of visiting him at his Florida home. John passed away a few days ago. I will miss him dearly.

— James Albright

Updated:

2019-11-20

I have a theory that every friend has a lesson in life for their friends that is a unique present of sorts. A friend need simply listen, be observant, and appreciate the lesson for what it is worth. John was never shy with his compliments. I tried to reciprocate as often, but my personality is terse and reserved by comparison. Now that he is gone, I understand the lesson he so generously gave to me.

Squadron Life

The 9th Airborne Command Control Squadron was a product of the Cold War. Our mission was to fly the Navy admirals in charge of the Pacific nuclear submarine fleet to wherever those submarines happened to be. In the seventies the airplanes were fairly new, well maintained, and kept as pretty as possible to match the stature of the passengers. I got to the squadron in 1982 for the tail end of that high status and it was a delight.

I started as a first lieutenant copilot and worked my way through the system. By 1985, when John showed up, I was the wing's chief of flight safety and only flew as an instructor pilot a few times each month. I was in the right seat instructing an upgrading pilot in the left seat with John in the jump seat when the airplane started falling apart on us. I simply wrote in my logbook that an engine had exceeded temperature limitations and we shut it down. And then we lost a hydraulic system. I don't remember much more than that, other than I called the training sortie short and returned to Honolulu.

That was how it went that year in the squadron: the airplanes were falling apart. I think we got to the point where shutting an engine down was just something that happened now and then. The biggest threat for most of us was the squadron commander, not the airplanes. Lieutenant Colonel Jerry Spindler appeared to believe leadership could be measured by how many of his pilots hated him. By that measure he was a great success. Most pilots endured as best they could and blew off steam by complaining at the bar and whenever on a trip without Spindler. That was easy to do, since Spindler rarely flew trips.

John was an exception to the steady stream of complaining pilots. He made fun of it all. A Spindler order to squadron pilots to stop aborting missions led John to admonish aircraft who refused to keep in one piece. A Navy Admiral's strongly worded lesson about crews getting into trouble in Okinawa led to some John Davey graffiti about Spindler's iron hand on his Okinawa crews. The cartoon was crossed out with the explanation, "Oh wait, Spindler has never been to Okinawa."

By the time John showed up, The Tale of Four Bruces story had started to fade. I was the copilot on Crew Five when we got into some serious trouble with a Navy admiral in Tokyo. The squadron call sign was "Mango" and each flight crewmember was known by a number that started with the crew number and then the position. As the copilot on Crew Five, I was officially "Mango Five Two." Mango Five One decided we were all Bruces so I became "Bruce Two." We four Bruces got into some trouble in Japan, drawing the anger of a Navy Admiral. The Admiral, a three-star, was a bit of a hero in the Navy and the name "Bruce" was the nexus of the problem. That week's problems cascaded to almost being intercepted while penetrating an Air Defense Identification Zone, again the name "Bruce" was a pivotal issue. Not good. See The Tale of Four Bruces for the story. By 1985, I thought everyone had forgotten about the Tale of Four Bruces.

John was on a trip in Riverside, California supporting our Navy passengers when I was scheduled to take the trip over with my crew. We flew in the night before in a different bird, and were scheduled to take the airplane John's crew had been flying. That morning John kept pestering me, "You been to the airplane yet?" He was anxious for me to get to the airplane, not something most copilots would care about. When I finally showed up, I found the cockpit littered with grease pencil marks. The pilot's windshield had in big letters, "BRUCE, SIT HERE." The attitude director indicator had, "Bruce's ADI." Hardly a dial, switch, or empty panel wasn't filled with Bruce graffiti. My copilot and I started erasing feverishly. It took us ten or fifteen minutes but we got it done just as the Admiral's car showed up. I didn't see him board the stairs but I heard him turn left instead of right. I turned in my seat to see the three-star from our Tokyo incident, three years ago. He smiled broadly. "Do you mind if I take the jump seat for takeoff, captain?"

Once everyone boarded, we started engines and took off. It was a sunny, California day and the Admiral unbuckled his belts to look out the windows. "Nice view up here," he said. "Yes, Admiral." I spotted naval aviator wings on his chest but wasn't sure if they were the wings of a pilot. He never asked any pilot-type questions. Once we leveled off I lowered my feet from the rudder pedals and saw a big letter "B" on the left pedal and a "R" on the right. I replaced my feet. Finally the Admiral left the cockpit. I looked to the right seat to see "U" and the copilot's left pedal and "CE" on the right.

Stan/Evil

The squadron started to run out of instructor pilots that year and after our standardization and evaluation pilot was hired away, we had a vacancy. The rules said the position could only be filled by an instructor pilot who had never busted a checkride — a silly requirement — and I found myself with the job. John Davey had already been hired as the standardization and evaluation crew's copilot.

"Welcome to stan/evil," he said as I walked into my new office. "We have the mother of all inspections next year and we are going to fail. I think that's why the old boss left. The king is dead, long live the king!"

The program was indeed a mess. But we had the top person of every crew position, ten of us, and with a little work we got everything up to speed. Our wing's inspection ended up earning to top score in the command that year and our stan/eval office was named the best of the year as well. You can read all about this: Flight Lessons 2: Advanced Flight.

Fear and Loathing Out of Uniform

I left the squadron later that year and the Air Force fourteen years after that. John turned down left seat upgrade and got out of the Air Force two years later.

John had the magic touch with money and I'm not sure what his secret was. He first venture out of uniform was to open a restaurant in Okinawa overlooking a U.S. Marine Corps runway. The restaurant had an aviation theme to it, including piped in chatter from the airport's tower. I visited twice. The food was very good but the tables were empty. The restaurant failed within a year.

John moved back to his childhood home and started a furniture business. That didn't last long. We talked about his business failures over a beer or three. "The problem, James, is that you have all those good ideas and no money. I've got all this money and no good ideas." I wasn't sure how to answer that. A friend of his asked him to sit right seat in a light airplane for a flight to Boca Raton. John flew south and never returned.

In the late nineties John decided he would become an Orlando area real estate mogul. As far as I know he only had one deal. He bought a lot of land cheap and sold it to a guy named Disney.

For the last twenty years John has faced more than his share of medical and family problems but has faced each with his uncanny ability to crack a wry, F-bomb laced joke about whatever it was that was making his life difficult at the moment. Despite whatever challenges were facing him, I always got an email, letter, or video he had crafted thanking me for my friendship, service to country, or just being who I am. I almost always returned the compliment, but not nearly enough.

His videos were carefully crafted and almost always with a pro-military flavor to them. He almost never bothered me with his health problems and I only found out about each bout with cancer after the treatment was well underway. He gave me a hint of what was to come almost a year ago. John tends to write in all caps so I'll post what he wrote to me verbatim:

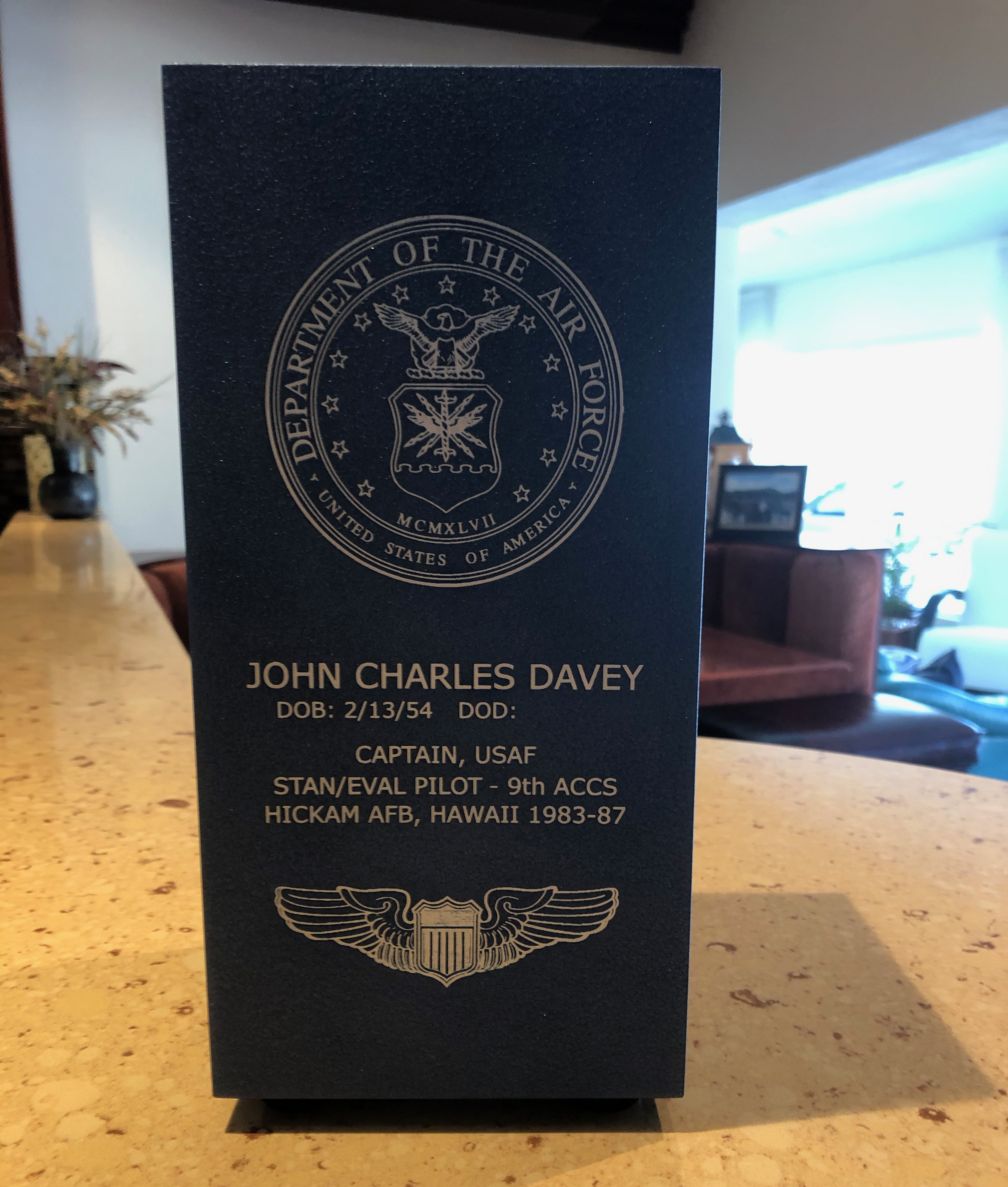

I LIVE ALONE SO I BOUGHT MY OWN URN. HOPING TO BE BURIED IN THE NATIONAL CEMETARY OF THE PACIFIC. IF NOT, BURIED AT SEA A QUARTER MILE NORTH OF MICHELS RESTAURANT AT THE FOOT OF DIAMOND HEAD. THAT'S WERE I NEARLY CAUGHT THAT 850 POUND GREAT WHITE SHARK. SHARKS LIVE 70 YEARS, SO, THAT FUCKING SON-OF-BITCH MAY EAT ME YET.

ALOHA, JC DAVEY-THE BIGGEST PAIN-IN-YOUR-ASS

I look at that urn and still wonder about what how he viewed his time on earth. He was an Air Force pilot during the time those wings were pretty hard to get. "CAPTAIN, USAF" is what you would expect to see on an officer's headstone or urn. I fully understand "STAN/EVAL PILOT - 9th ACCS" too. I feel honored to have shared that time with him.

You never know what impact you have on people, so make sure that impact is a positive one. The impact John had on me was the way he never failed to remind me of that impact. That dovetails with another tenet of mine and that is to show gratitude whenever you can because there are two beneficiaries. The person you show gratitude to should know they have had a positive impact on you. But it also helps reinforce in you your own positive qualities and just how lucky you are to have known them. I was very lucky to have known John Davey.