If, like me, you lived through the events of April 11 to 17, 1970, your memories of the Apollo 13 might be mixed with a yawning “oh yes another moon shot,” followed by shock, anxiety, and finally relief. If you weren’t around then, you probably got a pretty good idea about all this from the movie “Apollo 13,” starring Tom Hanks as Captain James Lovell, USN (retired), the commander of the mission. The movie came out a year after Lovell’s book, “Lost Moon.” After the success of the movie, the book was renamed “Apollo 13.”

— James Albright

Updated:

2024-12-09

Let me first say the movie is excellent. It does a very good job of capturing the drama, the heroism of the astronauts, and the hard work behind the scenes at NASA. The screenplay balances the technical details with the emotion and results in a suspenseful thriller. The visual effects stand the test of time, even all these years later.

So why bother with the book? From a professional pilot’s perspective, there is a lot to learn that runs contrary to conventional wisdom. Let me cite three examples.

Crew Resource Management

The movie does a creditable job showing the teamwork in the spacecraft as well as down on earth. But there is something in the book that captures the humility needed in command, the need to have a second set of eyes. For example, after they decided to power down the command module and escape to the Lunar Excursion Module (LEM), Lovell needed a set of numbers from the command module that would require further computation back at the LEM.

But as the commander copied the numbers onto his scrap paper and prepared to perform the necessary calculations, he was seized by a momentary and unaccustomed uncertainty. Could he perform the calculations properly? Would his ciphering be correct? 3 times 5 is 15, isn’t it? 175 minus 82 is 93, isn’t it? With the clock ticking down and so much riding on these rudimentary calculations, Lovell all at once found himself doubting his ability to add and subtract.

“Houston,” Lovell said, “I’ve got some numbers for you, but I want you to double-check my arithmetic so far.”

The Houston controllers were confused at first, but said okay. After some silence, they responded, “your arithmetic looks good there.”

p. 130

Systems knowledge

There is a cadre of professional pilots who believe that if it hasn’t been taught in the simulator, they don’t need to know it. I heard as much from several airline and business jet pilots, who thought I was wasting my time going deeper into the books. The amount of simulation time behind each Apollo mission easily dwarfs anything any of us earthbound pilots have done in a career. And yet, despite all that, the scenario that played out during Apollo 13 had not been anticipated and relied on everyone going beyond the books and simulators. I’ve lost engines during takeoff, had two cabin fires, lost pressurization a few times, lost complete hydraulic systems, and have seen more electrical problems than I care to remember. My simulator training helped for most, but not all.

Individual heroism of those other than the pilots up front

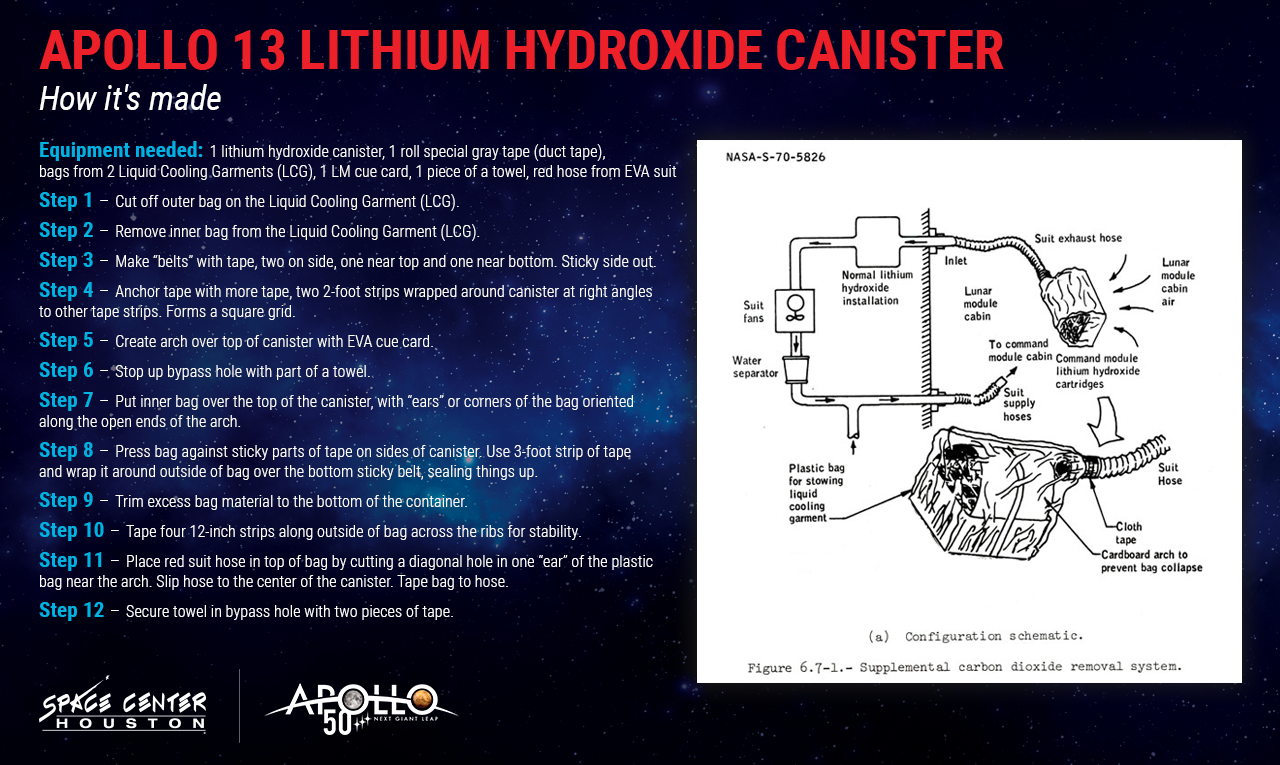

One of the more riveting scenes in the movie happens after the three astronauts leave the 3-person command module for the 2-person LEM and power down the command module for the journey back to earth. They didn’t have the necessary power to keep the command module operating during the transit, but the LEM didn’t have the environmental systems to support 3 people for the long journey home. The problem wasn’t a lack of oxygen, it was carbon dioxide. Both the LEM and the command module used lithium hydroxide air filters to remove the carbon dioxide from the air. But the round filters in the LEM were only designed for a crew of two and only for the trip from lunar orbit to the moon and back. They would be filled to capacity long before the trip to earth was completed. The filters in the command module could be used, except they were square. In the movie, an engineer throws a bunch of equipment on a table and tells his staff, “We got to find a way to make this,” while holding the square filter in one hand, “fit into the hole for this,” holding the round filter in the other hand, “using nothing but that,” pointing to the equipment on the table that represented what was available to the crew. The team of six got to work and saved the day.

Very exciting stuff, but it didn’t happen that way. What really happened, according to the book, was a single engineer, Ed Smyle, thought of the solution on his own while driving to his lab after hearing about the problem. Smyle wasn’t one of those engineers in the glamour positions seated in mission control in front of the nation’s television sets. No, Smyle was one of many anonymous engineers squirreled away in a lab that would never be seen by the press or the adoring public. But it was Smyle who saved the day. And the lesson for us aviators is clear. We may have the glamour positions up front of our aircraft. But our lives depend on those unseen heroes, like Ed Smyle. The next time you have a problem in your airplane that requires a square peg into a round hole, pick up the phone and call an expert. You might end up with another Ed Smyle. If you need to do that, you need to have a robust phone book at the ready.

These are just a few examples, but I think they illustrate the point. The movie is entertaining. The book is educational. A thoughtful aviator will learn from the book.