If you are flying a multi-engine aircraft, you probably have an instinctive understanding about the importance of using the rudder to keep the airplane flying straight. But you might not have such an automatic understanding of the need to apply the right amount of rudder to keep the airplane climbing. I've heard this called the "Goldilocks Effect," where the amount of rudder can't be too little or too much; it has to be just right. When I first heard the reason too much rudder can keep you from climbing, it was described as the "Barn Door Effect." And that was all the explanation I needed.

— James Albright

Updated:

2025-02-15

Think of an old-style barn door, one on hinges not one that slides. Think how much effort would be needed to open that door with no wind and then doing the same with a strong wind blowing directly to it, to keep it shut. The more wind, the harder it is to push. And what happens if you open it too far so now the wind is trying to force it open? It gets away from you and goes full open. It is vitally important to open the door only as much as needed and no further. Your rudder is a barn door and the chances are the bigger the airplane, the bigger the barn door. Too much rudder means too much of that barn door is out in the relative wind creating drag. But it is even worse than that on many airplanes where going too far can be fatal.

1 — The barn door and spoilers

2 — Technique: Center the yoke

3 — Technique: Add the slip indicator to your scan whenever changing rudder pressure.

1

The barn door and spoilers

Why too much rudder hurts you

On the runway for takeoff, prior to engine failure

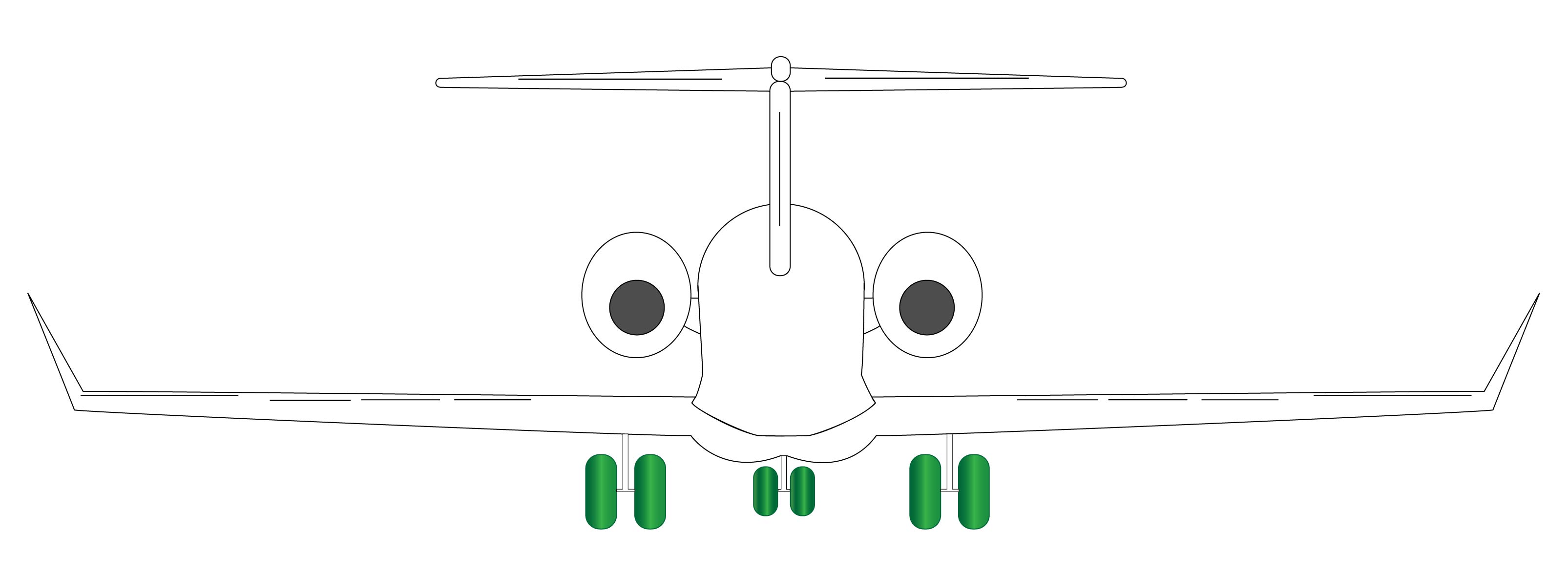

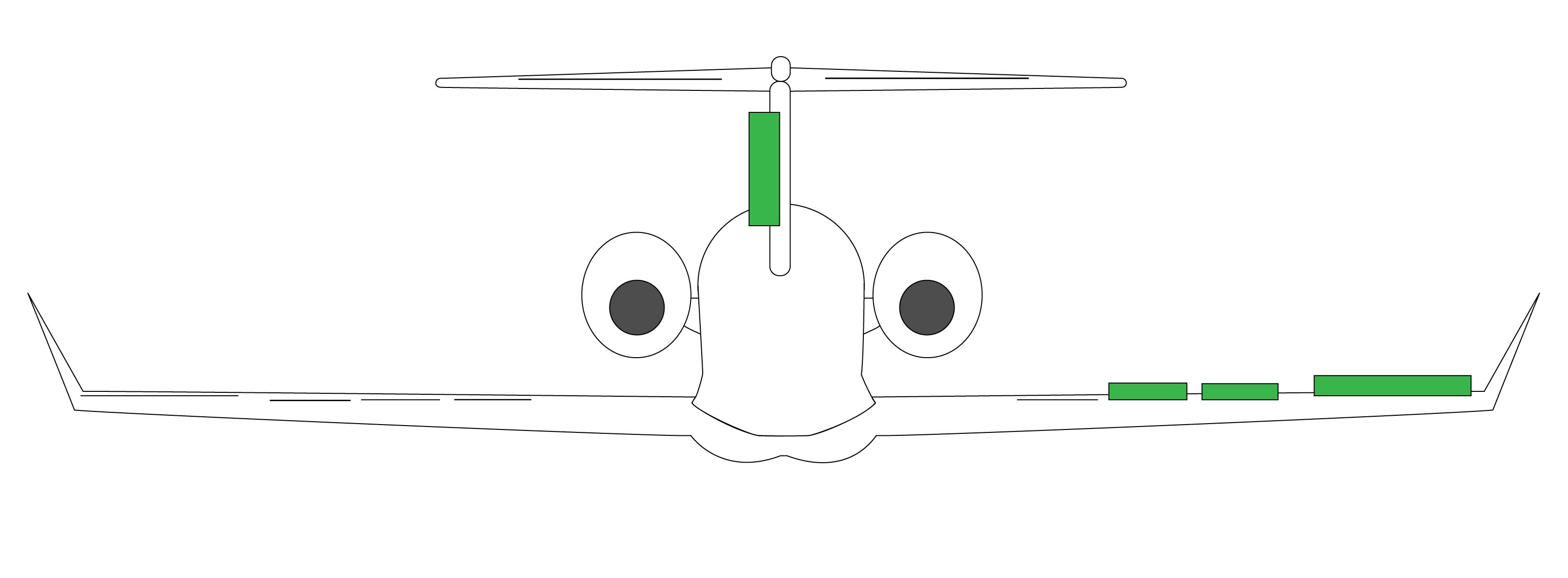

Consider a twin-engine jet speeding down the runway, just prior to V1, with both engines churning and no appreciable crosswind. As is typical with many such airplanes, the spoilers are interconnected with the ailerons to provided additional roll control. The rudder and ailerons will be streamlined and the spoilers will be flush with the wing.

On the runway, just after engine failure

Now let's say the right engine fails at V1, with the aircraft still in a three-point attitude. The nose starts to track to the right. The nosewheel helps to keep the aircraft pointed down the runway, but you will need some left rudder.

Rotation, gear retraction, initial climb, just enough rudder

Once you rotate and the nosewheel loses contact with the runway, you will need more rudder. Once the gear is retracted and your airspeed settles on the right speed, usually V2 to V2+10, the rudder requirement should stabilize. But how much rudder?

Answer: it depends. The rudder may have been sized to provide just what you need for the worst combination of thrust and weight. You will probably find yourself with less than full rudder on some aircraft.

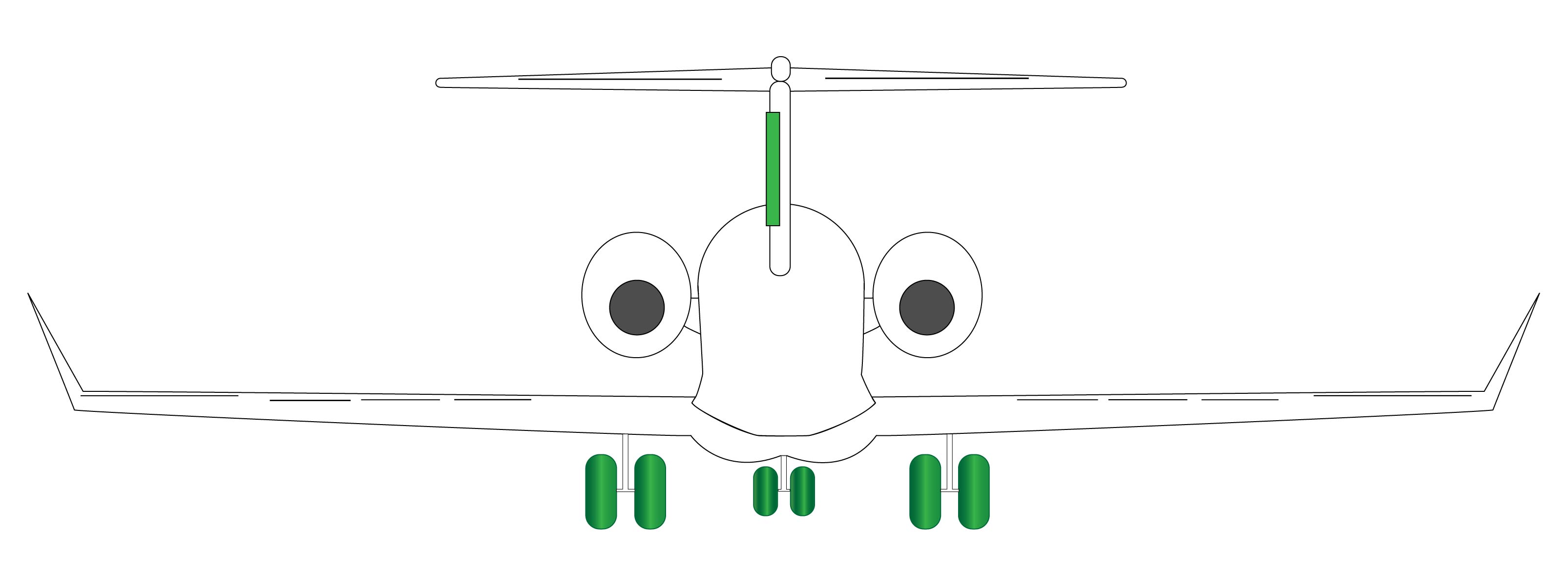

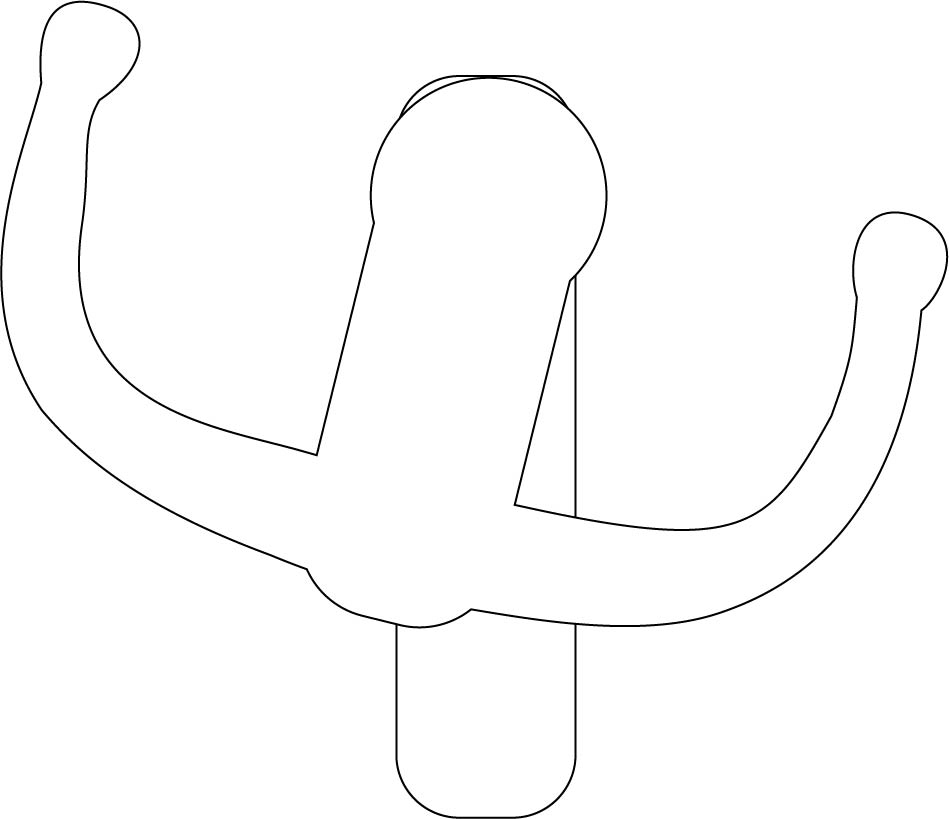

A little too much rudder

If you apply more than the amount of rudder to counteract the adverse yaw of the failed engine, the aircraft will tend to roll in the direction of the extra rudder. (In the example, to the left.) You may have a subconscious tendency to correct with aileron. (In the example, to the right.) I had a tendency to do this early on and every now and then when I forget to keep an eye on the tendency. This might not be a problem if the aircraft isn't too heavy or the environmental conditions leave you with excess thrust. But it will decrease your climb performance because you will have the added drag of the excess rudder and aileron.

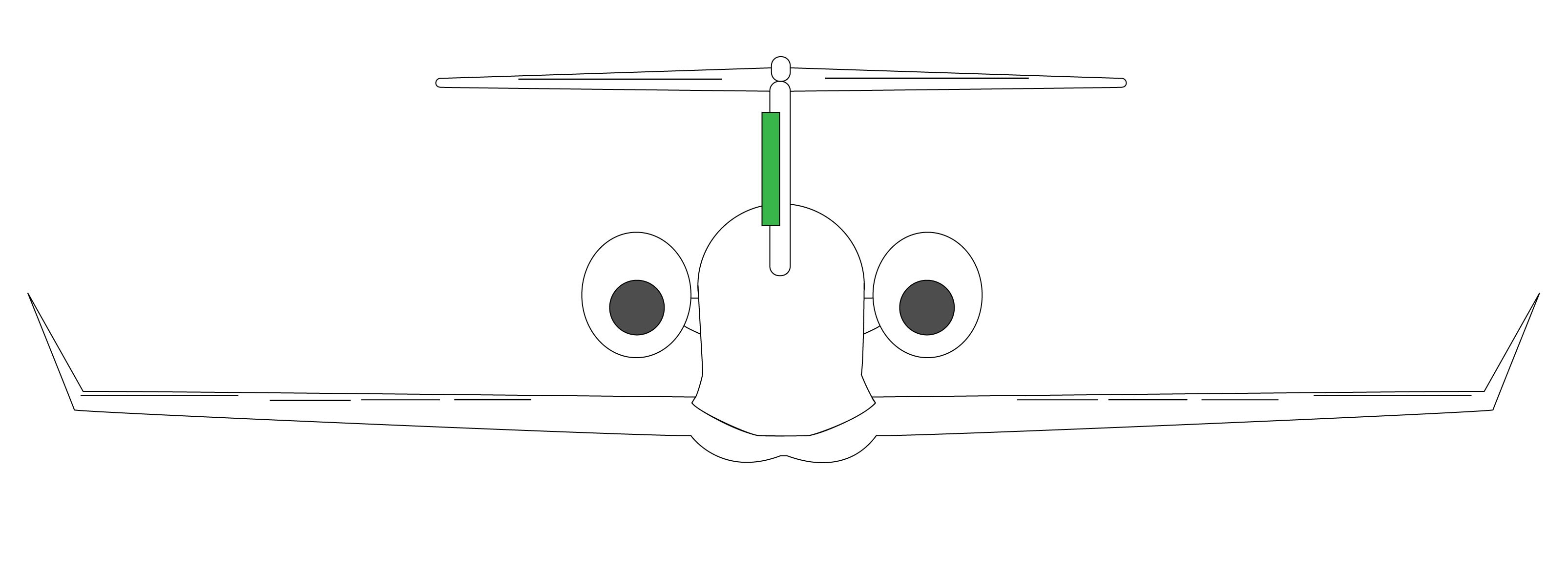

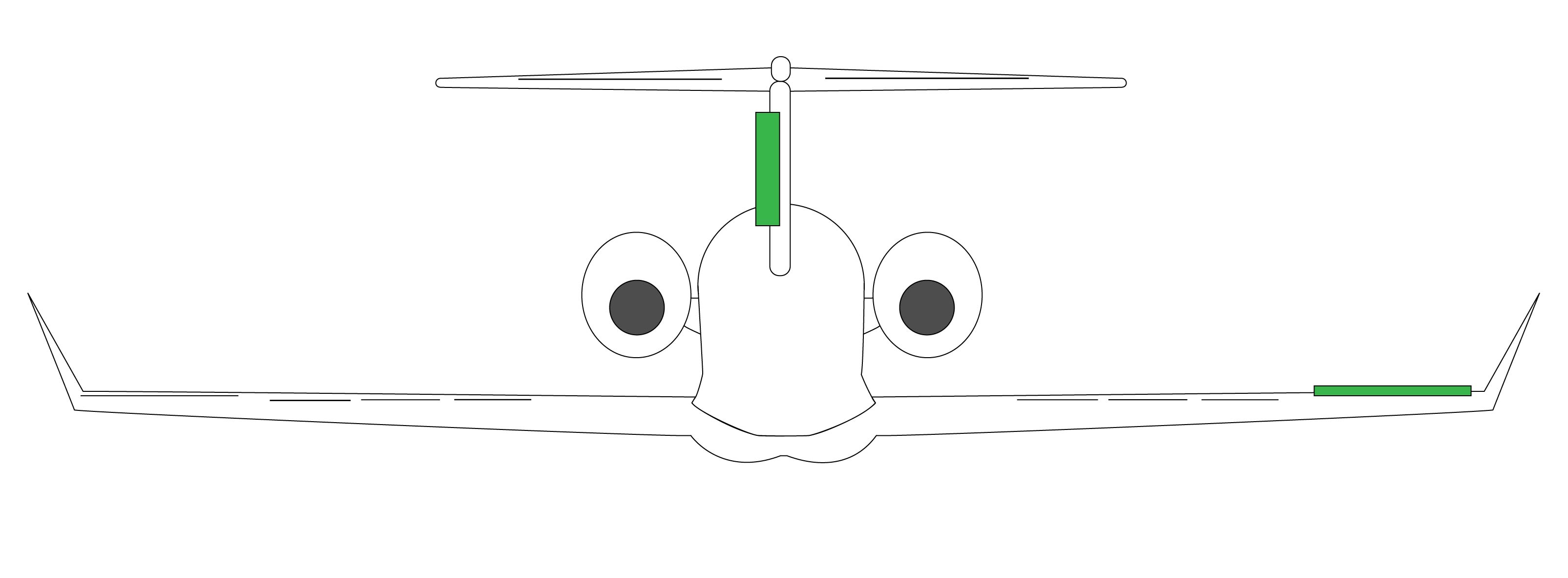

Too much rudder

If your spoilers are interconnected with the ailerons, there will be a point where too much rudder causes aileron deflection and then spoiler deflection. The amount of extra drag can be the difference between climbing and descending. I found myself in this situation in the Boeing 747 simulator during training on the way to my Airline Transport Pilot rating. All about this: Flight Lessons 2.

2

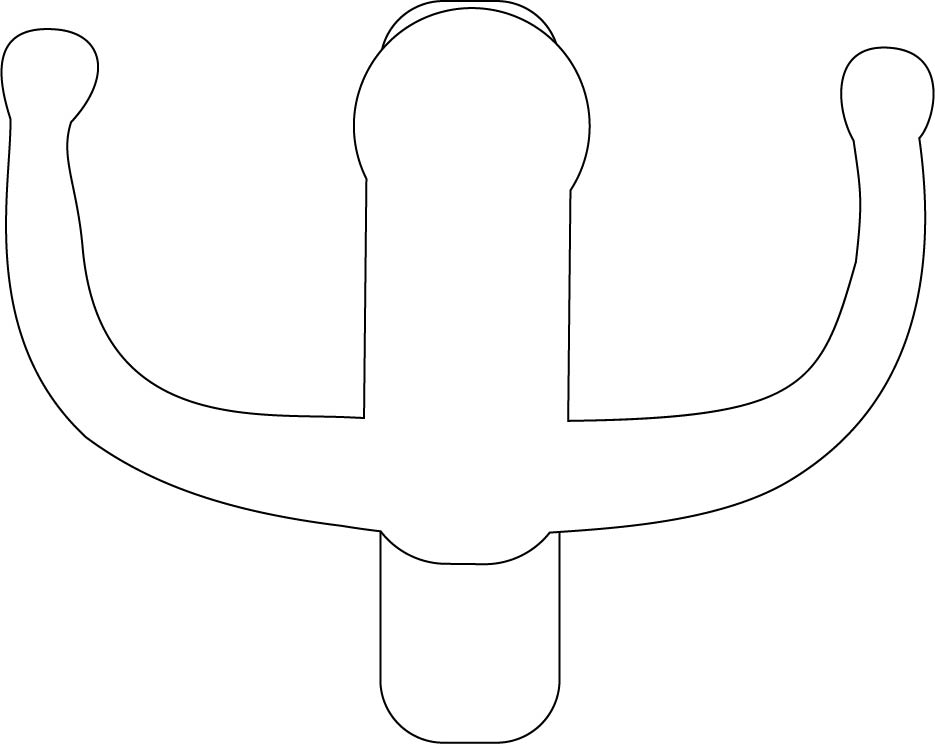

Technique: Center the yoke

An easy and tactile way to ensure the rudder is "just right"

Look at the yoke

If you have a yoke, you can tell if one side or the other of your ailerons are deflected if the yoke isn't centered. To fix this, center the yoke and adjust the rudder to level the wings.

Center the yoke

This is more difficult to do with a stick, especially a side stick. But adding the aircraft's slip indicator will solve that.

3

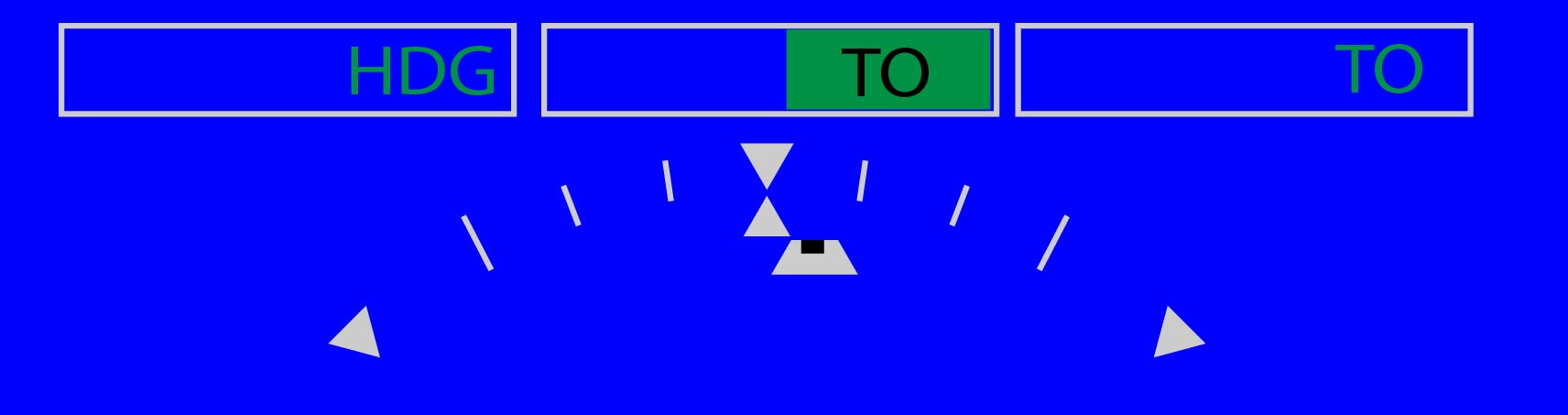

Add the slip indicator to your scan whenever changing rudder pressure.

So simple, but so often forgotten

Whenever you move the rudder, check the slip indicator

We should be well practiced at checking the slip indicator after we've rotated just to make sure we have the correct rudder applied, or to decide which rudder to press if the failure happened off the runway. But how often do you look at it after that? I've developed the habit of always checking the slip indicator whenever I moved the rudder or remaining throttle(s) if I have an engine failed. Every now and then when in the right seat in the simulator I see a pilot who is flying in a sideslip and I'll say, "check your slip indicator." That always fixes the problem.

I suppose if you've never flown with a large barn door for a rudder, you may never see this issue. But if you ever find yourself not climbing as well as you should with an engine failed, it might be a good idea to say to yourself, "check your slip indicator."

4

Case Study: United 863

In training: too much. In the airplane: too little.

First, a short story

It was a dream come true. I was over 500 hours short of the 2,500 hour minimum required to be selected to fly for a prestigious Air Force unit flying Boeing 747s. The interview had gone well and somehow I got selected. Since the Air Force didn't have enough 747s to do initial training, I was sent to United Airlines to complete the Boeing 747 Captain's Course. The squadron commander told me the last candidate they sent through had failed the check ride and that if I failed, I needed to find another job. And there I was, about to fail the check ride.

The check ride was in three parts: the oral, the simulator check, and the airplane check. I had one more practice simulator to go and had yet to survive what Dave, the United instructor, called the "ball buster." I had to survive an engine failure at V1, taking off from San Francisco's Runway 28L. We would be at maximum weight flying a Boeing 747-100, the most underpowered version of the aircraft. At first I was too timid with the rudder and we ended up in San Bruno mountain, our hundreds of passengers sent to simulator hell. "T-procedure! T-procedure!" Dave would yell. The "Terrain Procedure" required strict adherence to maintaining a specific heading until beyond the terrain. I got better with the rudder and maintaining the required heading, but then I was never able to out-climb the terrain. Dave's only critique was hardly useful: "You Air Force guys just aren't as good as airline pilots." I had just turned 30 and the youngest United 747 captain at the time was 56. Dave didn't like me.

The night before Training Simulator Number Last, I sat down and thought about the task of taking off with three of the four engines operating. In my recent experience, flying the EC-135J, a Boeing 707 with large (for the time) turbo fan engines, losing an engine at V1 never seemed to be a problem. But a few years before the EC-135J, I flew KC-135A tankers, with pure turbo jet engines. The tanker back then was grossly underpowered and losing an engine required quite a bit of finesse on the rudder. "You got a big barn door out there flapping in the wind," the instructors would say. "Why is it called a barn door?" I'd ask. "Dunno," they'd say. "It just is."

So what happens when you have too much rudder "flapping" in the wind? Sitting in the hotel room, before the last training sim, I realized it was more than the rudder. Facing the San Bruno mountains, I was sure to have enough rudder to keep us pointing straight, away from the airplane-eating-mountain. But maybe I was using too much rudder, fearing the mountain. With too much rudder, the aircraft would tend to roll into the rudder. So maybe I was subconsciously adding right aileron, another control surface "flapping" into the wind.

The next morning, sitting on the runway getting ready for the "ball buster," I mentally rehearsed what was to happen. It would be four engines to V1 and then the Number Four engine would fail. "Step on the good engines." Not all the rudder, I knew, but I would need all the rudder once airborne. And that is what happened. After I rotated I knew to add all the rudder I had left. Once the gear was up, the heading indicator behaved itself but our climb rate was anemic. I looked down to the yoke and noticed it was deflected to the right. Right aileron! I cross checked the slip indicator. Sure enough, it was deflected to the right. I backed off on the rudder until the slip indicator was centered. Another cross check: the ailerons were now centered too. I watched with satisfaction as our climb rate increased. The ball buster was conquered! Dave was impressed: "I guess some of you Air Force guys can make the grade after all." I managed another success for the simulator check and the oral and flight checks were no problem.

In the years to come, most aircraft I've flown have used spoilers to augment the ailerons for additional roll capability. And most of those aircraft included some kind of control position indicator in the cockpit. I began to notice that if a pilot was struggling to get the airplane to climb with a failed engine, more times than not, it was too much barn door causing the spoilers to deploy.

I never again struggled with the "ball busters" which followed. Aircraft with yokes gave a tactile clue that the barn door was "flapping in the wind." Without a yoke, the slip indicator never lies. You might have to chair fly this and practice it, but if you learn to cross check the slip indicator whenever you move the rudder with an engine failed, you will never again have a problem with the barn door.

The "close call"

The two pilots who followed me to the United Boeing 747 training program both failed their checks and we decided the problem was Dave, the world's worst instructor pilot. We refused to use him in the future and the pilots to come all passed. Despite all this, I thought the training was very good and United's emphasis on the "T-Procedure" has served me well over the years.

Years later, a United Boeing 747-400 with 307 people on board came within 100 feet of the San Bruno mountain. It seemed the first officer, who was the pilot flying, failed to maintain airspeed after the captain pulled back the Number Three engine which had exceeded temperature limits. When the stick shaker went off, the captain took over. Both pilots used ailerons to keep the wings level and the airplane on heading. That caused the same-side spoilers to deploy. It appears neither pilot used any rudder at all. This is the "Goldilocks Corollary" to the Barn Door effect. You don't want too much rudder or too little, you want to get it just right. More about this near disaster, Case Study: United Airlines 863.