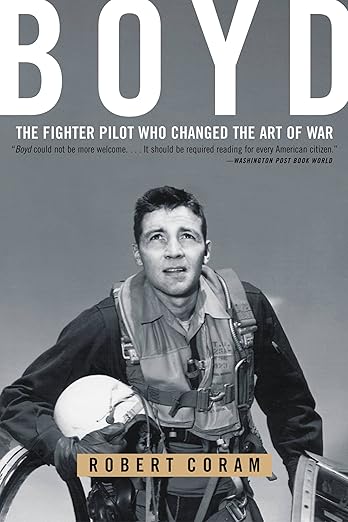

You might think the book title is a bit of hyperbole: “Boyd: The Fighter Pilot Who Changed the Art of War” by Robert Coram. But it isn’t. Colonel John Boyd was not only the fighter pilot I respect the most, but the Air Force officer I think deserved the most respect. He is revered and should be revered in each of the U.S. armed forces, but his legacy garners the least respect in the Air Force. And that is noteworthy. I won’t retell the book, which at over four hundred pages is lengthy. But every chapter is a page turner, worthy of close reading. Instead, I’ll summarize Colonel Boyd’s life into his most notable contributions to the art of war.

— James Albright

Updated:

2024-09-09

“Forty Second Boyd”

Boyd arrived late for his first war, the Korean War. The enemy wasn’t showing up for air battles so what was left was practice dogfights among friendlies and Boyd established his reputation as “forty second Boyd.” You could pounce on him and in forty seconds or less he would be on your tail for a “guns, guns, guns” kill. Nobody could beat him. How did he do this? Air-to-air tactics in Korea were pretty much as they were in World War I and II: you did all you could do to get behind the enemy long enough to take a shot. If the enemy got behind you, you did all you could to evade. Air combat was a turning battle, trying to get inside the other aircraft’s turn with enough airspeed to keep flying. Boyd changed all that. His innovation was to think ahead of the enemy, anticipate what they were going to do and then fly to take advantage of where the enemy was headed, not where he was. He would be on your six before you knew what happened. He was so successful, that he was invited to attend Fighter Weapons School, which came before the Navy’s Top Gun school, and then invited back to instruct. In all that time, Forty Second Boyd was never bested.

In 1964, as a captain, he wrote the “Aerial Attack Study” which was adopted by many Air Forces in the world as the definitive manual on air combat. For the first time, fighter pilots no longer had to learn “on the job” or in the ready room with more experienced pilots.

The study showed pilots how to best maneuver their aircraft and ways to defeat the enemy. He had turned the art of air combat into a science.

Energy-Maneuverability

One of the mysteries of the Korean War was how the F-86 Sabre was able to consistently beat the Russian MiG-15, which outperformed the American fighter on paper in almost every respect, such as thrust-to-weight ratio, climb performance, ceiling, and turn capability. American theorists just assumed it was superior pilots and left it at that. Boyd, still just a lieutenant, figured it was that the F-86’s canopy provided greater visibility, its hydraulic systems meant it could rapidly maneuver without fatiguing the pilot, and these factors meant the pilot could make decisions faster than their adversaries. From this, he developed an energy-maneuverability theory that reshaped fighter combat in two fundamental ways. First, pilots now thought of aircraft energy above and beyond airspeed. You trade potential energy in the forms of chemical energy (fuel) and potential energy (altitude), into kinetic energy (airspeed). Second, he quantified an aircraft’s ability to do all this into real numbers. And as it turned out, almost every U.S. fighter came up short. The E-M theory changed the way U.S. fighter pilots were trained and the way U.S. fighter aircraft were designed.

The Fighter Mafia

Boyd and a small band of followers that called themselves his acolytes fought a battle inside the Pentagon to combat ineffective and overpriced aircraft, which were usually darlings of the Department of Defense and the many companies behind these weapon systems. A prime early target was the F-111 which was designed to do all things for the Navy and Air Force but ended up doing nothing well. He also fought against procurement of the F-15 and managed to design a lightweight fighter without senior leadership’s knowledge. That fighter became the F-16. These battles were only prelude to the big war against the Pentagon to come.

The OODA Loop

One of Boyd’s most enduring contributions may be the OODA Loop—a strategic decision-making framework built around four iterative steps: Observe, Orient, Decide, and Act. This is something you do continuously in combat or other confrontational activities, just as your adversary is doing the same. After you figure out what the adversary is doing (observe), you gather situational awareness (orient) and figure a plan (decide) before executing that plan (act). Like his dogfighting tactic, the idea is to do this so quickly that by the time your adversary completes an OODA loop, you have moved on to the next. Your enemy’s OO are no longer valid so they are unable to DA, and the enemy becomes confused.

Boyd was a student of all things warfare and realized that the U.S. military had been flying with century old doctrines that never worked. He likened our way of fighting to the way of German General Carl von Clausewitz and the way we should be fighting to that of Chinese military theorist Sun Tzu. As Boyd put it:

“Sun Tzu tried to drive his adversary bananas while Clausewitz tried to keep himself from being driven bananas.”

Boyd, p. 332

Boyd was the first Air Force theoretician and perhaps the best in the military services of all time. His ideas resonated with lieutenant colonels and below with “boots on the ground” experience in Vietnam, while challenging the colonels above. In the battles to come, Boyd and his fighter mafia gained converts outside the Pentagon, inside the Congress, and with parts of the media.

The Pentagon Wars

Boyd and his acolytes produced study after study proving military acquisitions were overpriced, ineffective, and in some ways detrimental to the mission. They further showed that the doctrine taught in each service’s training programs were badly in need of reform. While each service benefited from many of Boyd’s ideas, only the Marines adapted his ideas enthusiastically into their doctrine. It is another irony that much of the credit for the success of the 1990 – 1991 Operations Desert Shield and Desert Storm can be directly laid at Boyd’s feet. And yet I would be surprised if any but the most ardent military historians knew that.

The sad life of Colonel John Boyd

Boyd had a single-minded focus on “doing good” and lived a spare life to avoid any temptations of the military industrial complex. His family lived in near poverty as a result, and he was a distant father and husband. When he died, he was in poor health, suffering from cancer and a series of strokes. Friends had to buy him clothes and pay for medical treatment because he had no savings. It is also profoundly sad that his own military service, the Air Force, to this day refuses to credit him for the fighter doctrine they now teach, or for the sorely needed Pentagon reforms that he shepherded.

Why was he such a pariah to his own services and to many in the Defense Department? I think it was his integrity. There is no better testimony of that than what is known as his “do good” speech. As it is often repeated, Boyd would say:

“Tiger, one day you will come to a fork in the road. And you’re going to have to make a decision about which direction you want to go. If you go that way, you can be somebody. You will have to make compromises and you will have to turn your back on your friends. But you will be a member of the club, and you will get promoted and you will get good assignments. Or you can go that way and you can do something—something for your country and for your Air Force and for yourself. If you decide you want to do something, you may not get promoted, and you may not get the good assignments, and you certainly will not be a favorite of your superiors. But you won’t have to compromise yourself. You will be true to your friends and to yourself. And your work might make a difference. To be somebody or to do something. In life there is often a roll call. That’s when you will have to make a decision. To be or to do? Which way will you go?”

Boyd, pp. 285 – 286

One last note about one of Boyd’s acolytes: Colonel James Burton. There is an excellent book called Pentagon Wars by Colonel Burton that goes into some detail about some of these battles fought at Boyd’s direction. I think it should be a must read for any officer assigned Pentagon duties. When I was an Air Staff officer at the Pentagon, the book had just come out. I didn’t read it until the year after I left. I wish I had read it sooner. While the movie puts its focus on an Army target of Colonel Burton’s Pentagon tenure, it is still worth watching. It is hilarious, but at the same time a bit sad. I wish I could say the Pentagon has been reformed since then, but all evidence suggests it has not. I’ll have a review of the book and movie next month.