If you are flying a jet single-pilot, the odds are stacked against you. But pilots fly jets single-pilot everyday without incident. How do they do that? For a starter, they use Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) that are mandated by company manuals and encouraged by active safety programs. They fly stabilized approaches and adhere to strict Crew Resource Management (CRM). Wait, CRM for a crew of one? Yes, but more on that later.

— James Albright

Updated:

2025-06-15

On September 20, 2022, a highly experienced pilot managed to land his Cessna CJ3 gear up on a clear day with light winds at an airport he was familiar with. He was well rested, and there were no external pressures exerted from the company or his 9 passengers. But he had one very big risk factor: the lack of a safety culture in his flight department. Let’s look at what happened, what the NTSB had to say about that, the why of it all, and finally how to prevent this from happening to you. Even if you fly in an aircraft that requires two pilots, these lessons will be invaluable to you.

Date: September 20, 2022

Time: 0709 PDT

Type: Cessna 525B

Operator: Pacific Cataract & Laser Institute Inc Pc

Registration: N528DV

Fatalities: 0 / 10 occupants

Aircraft damage: Destroyed, written off

Destination airport: Tri-Cities Airport (KPSC), Pasco, Washington

1

What happened

There are two sources of information, the primary of which is the NTSB Aviation Investigation Final Report. That report tells the public what they need to know about what happened and, for those in the business of flying airplanes, how to prevent it from happening again. You can download the report from www.ntsb.gov, selecting “Investigations” and eventually typing in the report number WPR22LA353. If you do read the report, you come away with what happened, but not why.

On September 20, 2022, about 0709 Pacific daylight time, a Cessna 525B (CJ3), jet airplane, N528DV, was destroyed when it was involved in an accident near Pasco, Washington. The pilot and 9 passengers were not injured.

The pilot reported that the flight to Tri-Cities Airport (PSC), Pasco, Washington, was uneventful; he reported to the tower controller that the airport was in sight and requested to land on runway 03L. The pilot further reported that, while on left base, he lowered the flaps to the first notch (takeoff/approach setting) and started to extend the gear handle. He did not recall confirming whether the gear was down and locked but reported that there were no landing caution annunciation or aural warnings. He said the flaps remained at the 15° setting for the approach. Before making contact with the runway, the pilot noticed that the airplane floated longer than expected and upon touchdown realized that the landing gear was not extended.

The airplane slid down the runway and came to a stop near the departure end of the runway. The pilot secured the engines and assisted the passengers out of the airplane. During the evacuation, the pilot reported that the airplane was on fire near the right engine. Shortly thereafter, the airplane was engulfed in flames.

The tower controller, using binoculars, noticed that the airplane did not have its landing gear extended and its bottom looked flush just before touchdown. However, the controller did not have enough time to notify the pilot.

A review of the ADS-B data revealed that the airplane’s groundspeed was about 143 knots as it passed over the runway threshold. Since the wind was reported calm, the airplane’s airspeed would be about equivalent to its groundspeed.

[Aviation Investigation Final Report, WPR22LA353, p. 3]

The report writers concluded that though the pilot “started to extend the gear handle,” he obviously did not. They investigated why the airplane’s landing gear warning horn didn’t sound. A look at the aircraft’s flight and operating manuals:

A landing gear or tone audio warning is provided by the warning/caution advisory system if either of the following conditions occur, and the landing gear are not down.

- Airspeed below 130 KIAS and either throttle is below approximately 85% N2. Warning can be silenced.

- Flaps are extended beyond the takeoff and approach setting. Warning cannot be silenced.

[Aviation Investigation Final Report, WPR22LA353, pp. 4 - 5]

For the accident flight, VAPP was 116 knots, but the pilot was flying above 130 knots and did not extend the flaps beyond the takeoff and approach setting. The conditions needed to activate the landing gear warning were not met.

The examination of the airframe revealed no evidence of pre-impact mechanical failures or malfunctions that would have precluded normal operation.

[Airframe Examination, Factual Report, October 14, 2022, WPR22LA353]

2

What the NTSB had to say

The National Transportation Safety Board determines the probable cause(s) of this accident to be:

The failure of the pilot to ensure the landing gear was extended before landing. Contributing was the pilot’s failure to fly a stabilized approach, and his configuration of the airplane that prevented activation of the landing gear not extended warning system on final approach.

[Aviation Investigation Final Report, WPR22LA353, p. 3]

As a former Air Force Flight Safety Officer trained in the art of accident prevention, this statement does little to help others to learn what is needed to prevent accident recurrence. It tells us what happened: the pilot used the wrong configuration for landing, flew an unstable approach, and forgot the landing gear. If all you read was the Aviation Investigation Final Report, you could conclude that if you always fly the correct configuration for landing, fly a stable approach, and don’t forget the landing gear, this won’t happen to you. But it did happen to this highly experienced pilot. Unless you understand how this pilot made all these mistakes, you won’t really understand why this airplane was destroyed. Until you understand the why, you will not know how to prevent this from happening to you.

The NTSB includes a summary of their investigation in the form of an accident docket, available at their website. You type in the same case number, WPR22LA353, and with a little research you might understand the why.

3

The why of it all

A Part 91 business jet

Pacific Cataract & Laser Institute Inc. Pc. (PCLI) employs a flight department to operate three Citation CJ3s and one Mustang under 14 CFR 91, based out of Tri-Cities Airport (KPSC), Pasco, Washington. The company has about 650 personnel, about 40 eye doctors and 12 surgeons, and uses the flight department to fly surgery staff members to various locations out-and-back, usually returning on the same day.

Based on interviews with the passengers, the flight department was highly regarded and its pilots highly respected. “She described the accident pilot as calm, cool, amazing, phenomenal, and a great pilot.” “. . . the accident pilot was more personable and serious about his job than the other pilots.” “She had flown with the other pilots and had no issues or concerns about the accident pilot.”

An autonomous flight department

The flight department is fully staffed with 4 company pilots and also uses about 4 contract pilots. There were no other personnel that reported to the chief pilot.

In this environment, the chief pilot built a flight department that can best be described as laissez-faire, pronounced “less-ay fair,” a French word that means “let it be.” The philosophy is minimal interference and no outside control. In the fight department environment, it means minimal effort. From the chief pilot’s interview:

There were no pilot meetings, emails, newsletters etc., occurring on a regular basis.

There were no formal safety programs at the company.

SRM/CRM was taught at FlightSafety.

No trend monitoring of stabilized approaches. He checked for them when he flew with other pilots.

There were no safety meetings held or a formal safety reporting system. He would receive safety information from informal calls, meetings, or from the surgery teams supervisors on issues involving the flights.

There were no company flight procedures or manuals.

[Memo For Record, Chief Pilot Interview, p. 2]

I’ve flown for two chief pilots with this mindset and in both cases I was alarmed by what can be best described as a lack of safety culture. The boss doesn’t care how you fly, only that you tick the box that shows the aircraft was flown without complaints. As long as you do that, the boss leaves you alone.

A training department that doesn’t teach

The accident pilot received his Citation training with FlightSafety and described the training as “great and that he was excellently trained.” He went on to say his Single-pilot Resource Management (SRM) was done by FlightSafety and “was useful and good.” The chief pilot noted that SRM/CRM was taught at FlightSafety.

In my opinion that sums up what happens at FlightSafety International and what other business jet training vendors do: they train but they don’t teach.

Training = learning how to do

Focus: skills and practical application

Goal: achieve the necessary skills and licenses to perform a specific job

Scope: narrow and targeted to a specific job

Teaching = understanding the why of what

Focus: knowledge, theory, concepts

Goal: understand and think critically

Scope: broader and beyond the specific task

The training vendor teaches you what you need to fly the airplane, that the checklist exists, and what constitutes a stable approach. The vendor gives you a check ride to make sure you can do all that they train. But once you’ve passed the check ride, it is up to you to employ the lessons learned. Without a thorough understanding of why the training is important – without the theory behind the skills – pilots are released into the system to fly as they please. If they are released into flight departments populated by similar pilots without adequate oversight, accidents are inevitable.

A pilot who fits in and sinks to the level of the flight department

The accident pilot was highly experienced with nearly 10,000 hours total time, over 2,000 hours in type, and had been flying since 1976. He first flew for PCLI in 2007 on a contract basis and as a full-time pilot for the last 4.5 years. On the day of the accident, he was well rested.

- Descending into Pasco, he slowed down and started to configure the gear, when the tower called and cleared him to land on runway 3L.

- There was another airliner taking off from Pasco, that he was watching.

- He was concerned about the airplane but then it took off and was cleared to dept frequency and was out of the way.

- He then said the winds were stronger than he expected, and he was focused on maintaining centerline on the approach.

- He lowered the flap a notch (takeoff setting of 15 degrees).

- He also said a flock of birds caught his attention.

- He noticed normal power and pitch settings on final.

- Approach seemed normal until he heard the terrific sound on touchdown.

- He said the landing was smooth.

- He had no master caution light or annunciators during the approach and silence no audio warnings.

Details of the Approach

- He usually configures 1-2 miles on final.

- He remembers flying between 120-125 kias on final.

- The last time he looked, the airspeed was about 118 kias.

- You can hear the gear coming down in the cockpit and feel it too.

- He did not get these indications on this flight.

- He had the flaps partially set to 15 degrees.

[Memo For Record, Chief Pilot Interview, pp. 3 - 4]

What is particularly important about the accident pilot’s statement is that he never refers to the use of a checklist to confirm the landing gear is extended, he ends his configuration with “a notch” of flaps (the takeoff setting), and he never talks about a stable approach. Also important: his recall of the airspeed doesn’t match what was seen on ADS-B given the nearly calm winds.

In the pilot’s mind, the aircraft failed him. Under “Mechanical Malfunction/Failure” the pilot entered: “landing gear warning system failed to activate.” [Pilot/Operator Aircraft Accident/Incident Report, 09/20/2022, WPR22LA353]

As we’ve seen from the AFM, the landing gear warning system would not have activated given his excessive speed and flap setting.

Another key point: according to the chief pilot, “he usually configures on base.” According to the accident pilot, “he usually configures 1-2 miles on final.”

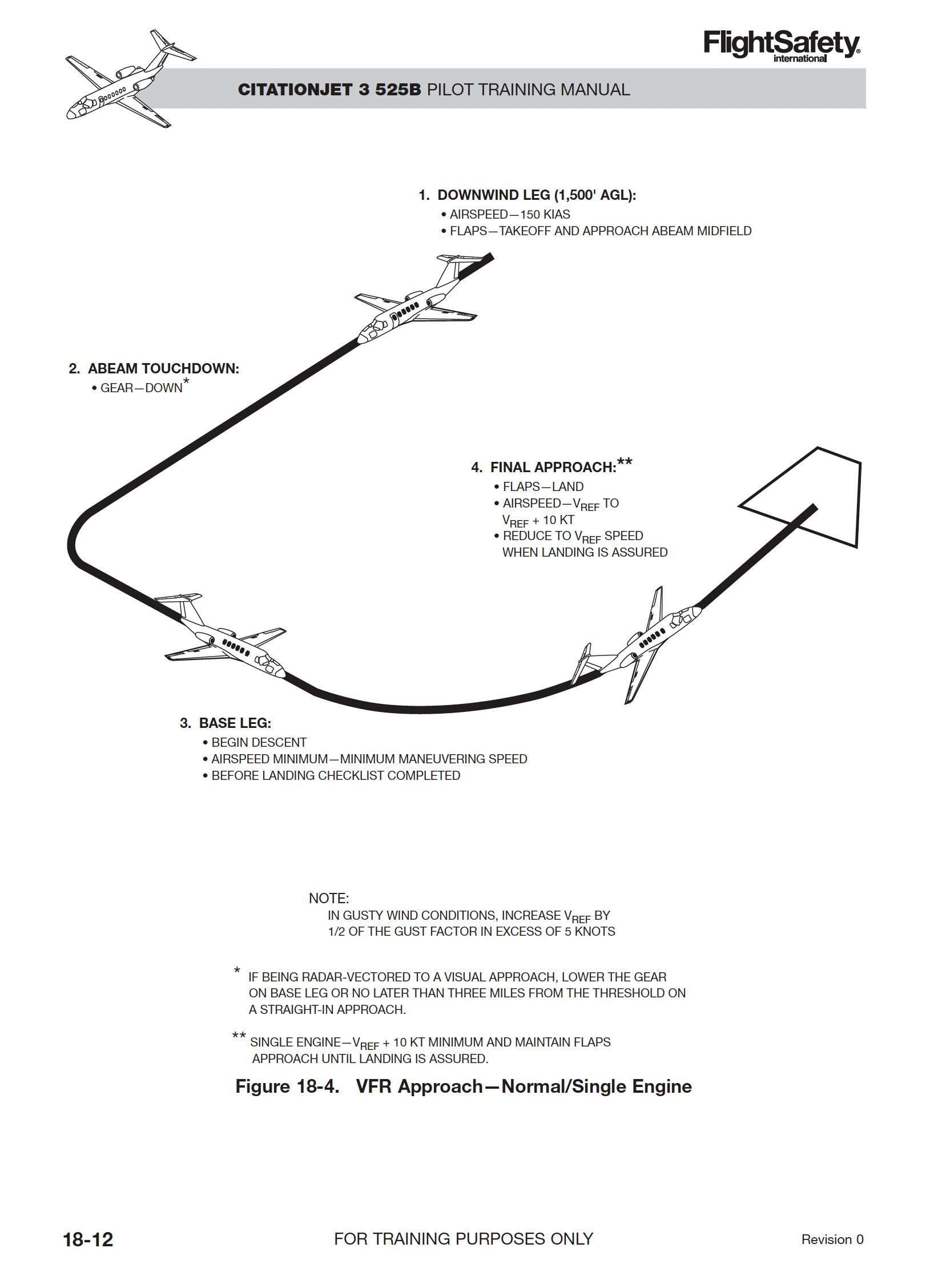

CitationJet 3 525B Pilot Training Manual, FlightSafety International, Original 0, August 2009, figure 18-4 (NTSB)

The training vendor’s CJ3 material agrees with the manufacturer’s manuals on several key points when describing a visual approach:

- The landing gear is extended on downwind, abeam the touchdown point.

- Flaps are moved from UP (0°) to the TAKEOFF AND APPROACH (15°) setting on downwind.

- The Before Landing Checklist is completed on base.

- Flaps are moved to the LAND (35°) position on final.

All of this is what should happen and is trained. But based on what actually happened, the pilot was in the practice of delaying extension of the landing gear until base, of landing with less than the prescribed flap setting, not using a checklist, and ignoring stable approach rules. The training vendor did not teach the importance of doing all this, only trained to ensure it happened in their simulators. His flight department did not have a safety culture that taught the importance of flying as trained and didn’t provide the oversight needed to ensure pilots were flying as trained.

Does any of this absolve the pilot of responsibility for this crash? No, not at all. But it does add to the suspect list:

- The training vendor failed to teach the importance of operating the airplane according to manufacturer manuals or the imperative of always flying a stable approach.

- The chief pilot failed to provide the necessary operations manuals and oversight needed to telegraph a culture of safety in its pilots.

- The National Transportation Safety Board failed to identify these two additional parties as causes of this accident.

4

How to prevent this from happening to you

CRM

How do you have CRM with a crew of one pilot? And why would you? If you look at the safety record of the Japanese high speed rail system versus those of any other country in the world, you will see how a particular CRM technique saves lives. That technique is called “Shisa Kanko,” or “Pointing and calling.” I’ve been using the technique for many years now:

You can see Shisa Kanko in action on the Japanese bullet train, called the Skinkansen, in this YouTube presentation:

https://youtu.be/9LmdUz3rOQU?si=vhM3HvRgD4aKcen2

High speed rail systems all over the world have experienced tragic derailments, killing far too many people, because the train engineers (pilots of a sort) forgot to do something critical. The Shisa Kanko technique requires verbal, visual, and tactile actions to ensure no steps are forgotten. Yes, you end up talking to yourself. Yes, this could save you a gear up landing.

Stable Approaches

The accident report cites the pilot for not flying a stable approach but doesn’t specify why the approach wasn’t stable:

- The airplane was not configured correctly by 500 feet. Not only wasn’t the gear extended, but the pilot had chosen a flap setting contrary to the aircraft manual.

- The aircraft was well above the correct target approach speed.

- The aircraft was in a turn, not aligned with the runway at 500 feet.

Many of us believe we always fly stable approaches, always. But we make an exception for visual approaches because . . . because why?

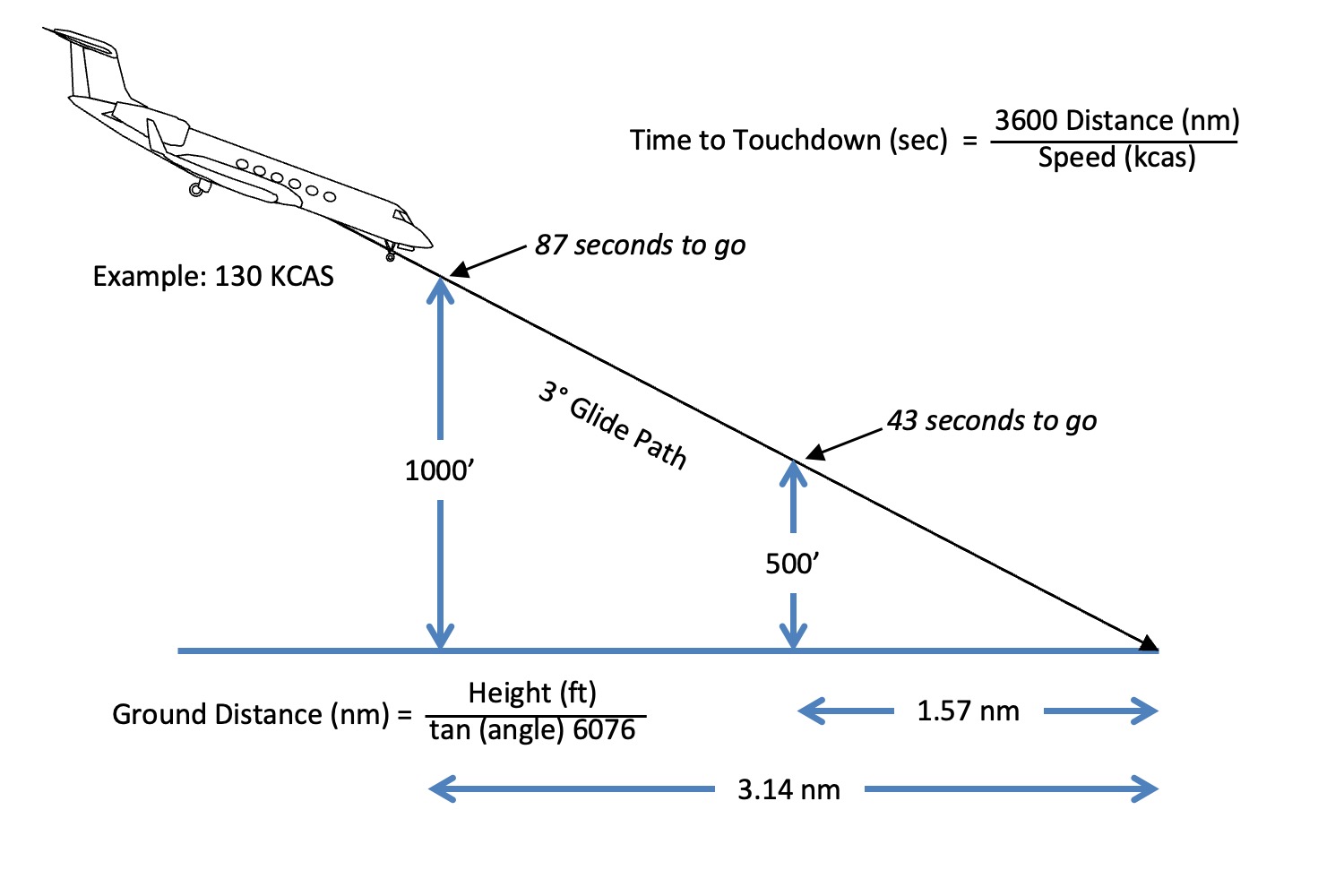

If you believe a stable approach is required no later than 500 feet above the runway – and you should – the minimum distance on a 3-degree glide path for that to happen is 1.57 nm from touchdown. If you are aiming for the touchdown zone – and you should – that subtracts 1,000 feet (0.17 nm) which means you need to be stable no later than 1.4 nm from the runway. For a 90° turn from base to final at most speeds, you need about ½ nm. As a rule of thumb, you need to aim for a 2 nm final to have any hopes of a stable approach from a normal visual pattern.

Safety Culture

In my view, the primary cause of this accident was the flight department’s lack of safety culture. We all think we are safe and would never say our flight department has a poor safety culture. If you do not have a Safety Management System (SMS), you might have a safety culture. If you do not have any company manuals that specify your SOPs, then I would bet that you do not have a good safety culture.

The first time I was contacted by a pilot complaining that their flight department didn’t have any operations manuals I was stunned. How could this be? But since then, I’ve heard from more and more pilots with the same complaints. In each case, the flight department in question lacked a culture which encouraged following aircraft manufacturer and applicable regulatory procedures.

In most of these cases, the root cause was the person in charge. This person, often called the “chief pilot,” didn’t see the need. “We’re doing fine without all that.” In many cases, it was a cost factor. “We don’t have thousands of dollars in the budget for that.” In all the cases, the underlying reason is a question: “why do we need a manual?”

The primary reason is simple: if you don’t specify Standard Operating Procedures, your crews will inevitably invent their own procedures. But there is another reason that should get your attention. The lack of a Flight Operations Manual (FOM), Company Operations Manual (COM), or equivalent document telegraphs to your crews that SOPs are not important.

So, let’s say you are convinced but the budget outweighs all. Years ago, I was contacted by a young Gulfstream GV pilot who was alarmed that they were flying all over the world without the necessary Letters of Authorization. Digging further, I found they didn’t have any written rules of any kind in their flight department. For checklists, they used the blue binders provided by FlightSafety at the time, the ones that say, “For training purposes only.” I gave her chapter and verse about the regulations that required even a Part 91 operation have the LOAs and some kind of flight department manual to fly over the North Atlantic. She approached the chief pilot and was told it wasn’t in the budget and there was nothing he could do about it. In frustration, she asked me, “what would you do if you were in my shoes.” I told her I would find another job and then quit. She quit before finding another job. The company CEO called her into the office and asked why. She didn’t blame the chief pilot, only the circumstances that prevented them from having the needed LOAs and manuals. The CEO offered to increase her pay if she would agree to get the missing documentation for them. She agreed and called me. “How am I going to do all this?

Long story short, she got it all done. Some of the LOAs required flight department manuals and SOPs, so that’s where we started. I believe using a vendor who specializes in these is the way to go, but that wasn’t an option for her. I was once in her shoes, so I wrote my own manual. I took that manual, made it generic, and gave it to her. She turned that into a manual for her flight department that was approved for the LOAs and then got the LOAs.

If you are in a similar situation, I have everything you need in Microsoft Word documents that will get you what you need, starting with SOPs and company manuals and ending with what you need for Safety Management System qualification:

Where to begin? I recommend you skim each section first and pick out the items you need the most. For most operators starting with no written SOPs, starting with Chapter Five may be the best choice. Cut and paste what you are ready for into a brand-new Word document and add to that as you get more and more comfortable. Remember to include the entire team in this. Don't feel like you need to do things my way. Remember that having a good set of SOPs makes flying more predictable, reduces the tendency to take shortcuts, fends off the normalization of deviance, and lowers cholesterol. I may have made some of that up. Good luck!

References

(Source material)

Airframe Examination, Factual Report, National Transportation Safety Board, October 14, 2022, WPR22LA353

Aviation Investigation Final Report, National Transportation Safety Board, October 14, 2022, WPR22LA353

CitationJet 3 525B Pilot Training Manual, FlightSafety International, Original 0, August 2009

Memo For Record, Record of Conversation, National Transportation Safety Board, WPR22LA353, various dates from September, 2022 to June, 2023.

Pilot/Operator Aircraft Accident/Incident Report, 09/20/2022, WPR22LA353