If you are a business jet pilot, you no doubt have heard about the sad case of Challenger 605 N605TR, which crashed while attempting to circle a Truckee-Tahoe (KTRK) Airport, California. You are probably familiar with the NTSB report which labels this as a loss of control in flight. Reading many reports, you may also agree that this was the case of a pilot who didn’t know how to circle in his jet and another pilot who lacked the Crew Resource Management skills to fix what was broken. On the other hand, if you are an airline pilot, you may have heard about this and concluded it is another case of business jet pilots who don’t know what they are doing and validation for the idea that you should never circle at all, as is the case with many airlines, or only in specific situations with specific training, as with other airlines. I am with the airline pilots on this one. But if you are a business jet pilot who has no choice in the matter, how do you learn to prevent this from happening to you?

— James Albright

Updated:

2025-04-15

N605TRNTSB Operational Factors, Photo 1

The NTSB did a good job of explaining what happened but not why. Their causal statement blames: (a) the first officer’s decision to salvage an unstabilized approach, (b) the crew ignoring stall warnings, and (c) the crew not properly setting up for the circling approach.

As a result, we train pilots (a) not to salvage unstabilized approaches, (b) not to ignore stall protection system warnings, and (c) do a better job setting up circling approaches. I think (c) leads to (a) and in the heat of battle that leads to (b). There is an easy solution to this that is being ignored by the NTSB, the FAA, and those who train us how to circle. But let’s first look at what happened that led to all this.

Date: 26 July 2021

Time: 1330 LT

Type: Bombardier CL-600-2B16 Challenger 605

Registration: N605TR

Fatalities: 2 of 2 crew, 1 of 1 passenger

Aircraft fate: destroyed

Location: Truckee Airport, CA (KTRK)

Phase: Approach

4 — The RNAV(GPS) approach to Runway 20, circle to Runway 11

1

The crew

An interesting dynamic

The crew presents an interesting dynamic in that the captain was relatively inexperienced compared to the first officer.

The captain, was 43 years old, had 5680 hours total time, 235 hours in type, and was the Pilot Flying (PF). His experience was mostly in older aircraft as a line pilot. The first officer, a contract pilot, was 56 years old, had 14308 hours total time, 4410 in type, and was the Pilot Monitoring (PM). His impressive resume included jobs as a chief pilot, training instructor and examiner, and airline captain.

The company, Aeolus Air Charter, Inc., was in the process of hiring the captain but, according to the Director of Operations, “because of him being of Mexico - - or didn’t have a visa or a Social Security Number we could not hire him” and “could only contract him.” The CEO, however, said the company hired him as a “contractor under 135.” But the Custom Border Patrol said he was not allowed to operate a flight for compensation in the U.S. because he had a B1/B2 United States visitor’s visa.

The captain had enrolled in the operator’s indoctrination training, which included instruction in the company’s General Operating Manual (GOM). The NTSB report notes that during his most recent training, “the instructor comments for the practice simulator sessions noted that he rushed checklists, needed to slow down and read the checklist requirements, and needed to setup approach procedures without PM prompts.”

As a contract pilot, the first officer had not been trained in the company’s GOM.

I think the resulting dynamic from the crew’s perspective, would be that the captain knows he is in charge, but looks to the first officer as somewhat of an instructor. The first officer knows he is working for and must defer to the captain, but that the captain needs considerable help as a crew captain and a pilot in a new aircraft.

2

The aircraft

Airworthy, but . . .

In my opinion, the Challenger 605 is a capable aircraft but can be a handful when flown in a gusty crosswind or in any conditions if flown below recommended speeds. When it stalls, it tends to fall off on a wing rather sharply. Older Challengers were required to circle at 150 knots but that restriction was removed and the specified circling speed was changed to VREF + 10 KIAS.

The NTSB report says the aircraft was airworthy, but the Flight Management System (FMS) had a 3,000 lb. error in the performance computer as a result of a recent battery change. When the battery is changed, the performance computer defaults to a minimum aircraft empty weight, which was 3,000 lbs. below the accident aircraft’s actual empty basic weight.

3

The flight to Truckee

The captain directed the first officer to program “the GPS” for Runway 11, which was a sound choice given the calm winds, the fact that Runways 11/29 were 7,001 ft. long and both had straight-in approaches, versus Runways 2/20 which were only 4,654 ft. long, and required a circling approach. The use of “the GPS” versus “the FMS” is indicative of the captain’s wealth of experience in the older Challenger 601 versus the newer 605. During the cruise and initial part of the descent, it became obvious the captain accepted the fact the first officer was more knowledgeable and was comfortable asking questions, even questions he should have known. “In which book can I see . . . where is all the equipment that this aircraft has?” While programming the FMS performance: “Twelve seats?” “What’s that meaning of LEMAC?” And finally, “I have (aircraft) work to do with you.”

From the CVR:

First officer: approach brief

Captain: So umm . . . depending on the visibility . . . I guess I’m gonna . . . I’m gonna shot anyway the . . . the R-NAV . . . or the G-P-S . . . If they . . . If they can allow me to fly the visual to [unintelligible word] if not . . . we do everything.

First officer: okay.

Captain: I mean we . . . we can request say can we fly to ALANT and if not . . . I mean we don’t see – just shoot the approach.

First officer: ‘kay. . . . approach brief is complete.

Source: CVR, pp. 33 -34

4

The RNAV(GPS) approach to Runway 20, circle to Runway 11

When the crew checked in with Oakland Center they were told to expect the R-NAV 20, to which the first officer said, “Roger that.” The captain said, “the runway’s too short . . . . for runway twenty . . . so we will have to circle to land . . . so we can’t . . . cannot accept that.” After more discussion about the performance numbers, the captain says, “we can make it and we can circle to land.”

As paltry as the approach briefing for the planned approach to Runway 20 was, there was no briefing at all about the circling approach to Runway 11.

_rwy_20_ntsb_wpr21fa286_atc.png)

Truckee RNAV(GPS) Rwy 20, NTSB WPR21FA286, ATC, Group Chairman's Report

As they continued their descent, the captain fell behind and the first officer offered warnings alternated with conflicting reassurance:

“Are you going to be able to get down.”

“You got plenty of time.”

“Gotta get this thing slowed down.”

As the captain slowed through 250 knots he said, “below two fifty give me flaps twenty.” The first officer reminded him of the correct VFE, “below two fifty? How ‘bout two thirty?”

And then, “start slown’ the puppy up.”

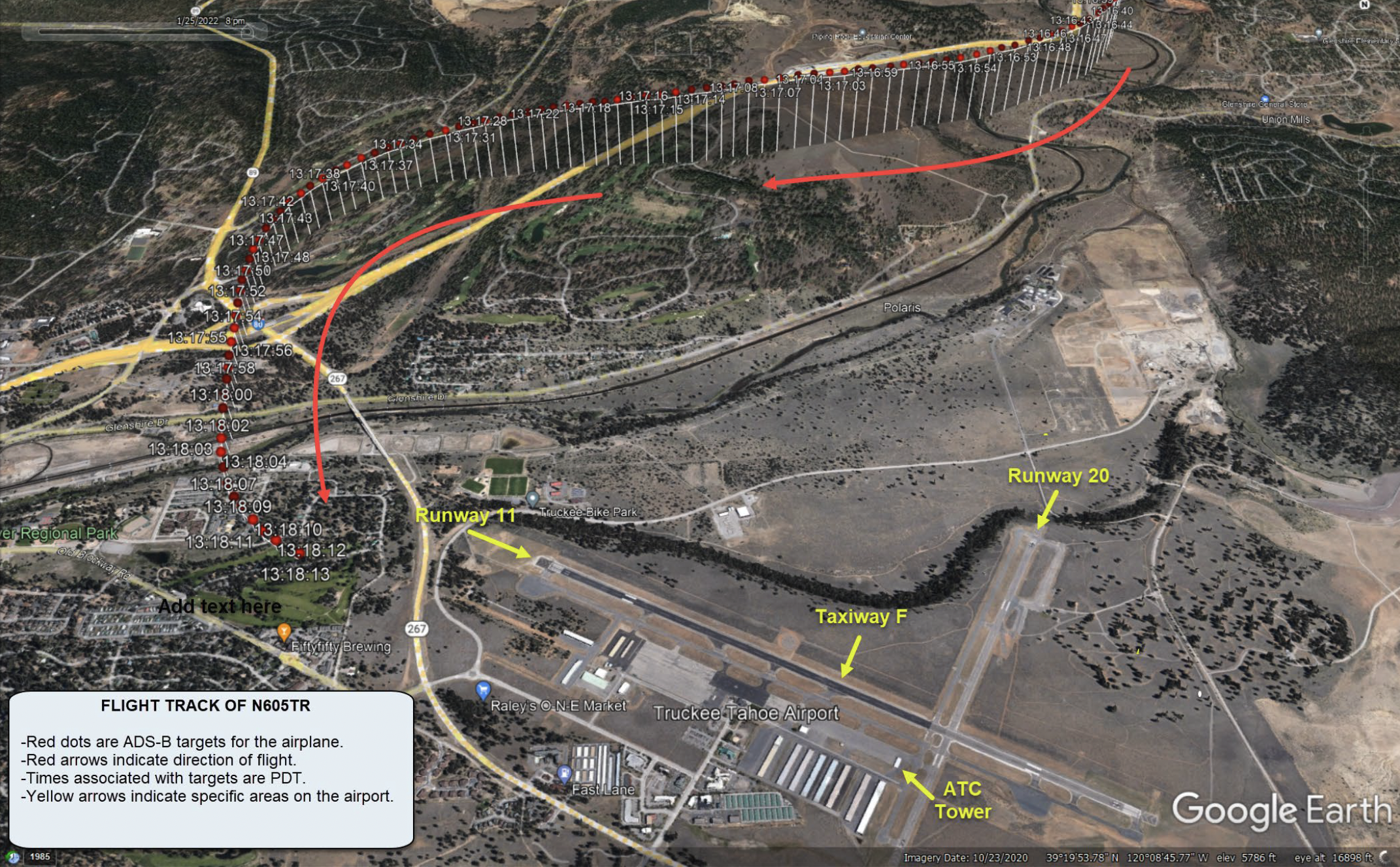

Flight track, NTSB WPR21FA286, ATC, Group Chairman's Report

The following extracts from the Cockpit Voice Recorder are from the last two minutes of flight, with my comments added.

13:16:12.1 Captain: uh...circle to land is seven...seven seven hundred.

13:16:15.0 First officer: what's that?

13:16:15.9 Captain: do you see the airport?

13:16:16.4 Cockpit Area Microphone: approaching minimums. [electronic voice]

First officer: no not yet.

13:16:17.9 First officer: final flaps ready for it?

13:16:19.4 Captain: full flaps.

13:16:19.8 Cockpit Area Microphone: [sound of lever moving]

13:16:20.4 Cockpit Area Microphone: minimums. [electronic voice]

13:16:20.7 First officer: there's the airport.

13:16:21.6 Captain: where?

13:16:22.8 First officer: right there.

13:16:23.8 First officer: make a right hand turn ninety degrees.

Source: CVR, pp. 57 - 64

This would place the aircraft on a 290° heading, parallel to Runway 11, a proper downwind.

13:16:26.3 Radio transmission: six zero five tango romeo is making the right hand turn we've got runway one one in sight.

13:16:30.4 Tower: november five tango romeo roger runway one one cleared to land wind calm [unintelligible].

Radio transmission: cleared to land six zero five tango romeo.

13:16:36.9 Captain: where?

13:16:37.5 First officer: you see that hangars?

13:16:40.5 Captain: yes.

13:16:40.9 First officer: you're at...you're going at them right...right there.

13:16:43.4 First officer: roll out.

Source: CVR, pp. 57 - 64

The captain dutifully rolled out and a heading of 233°, angling into the runway 57°, leading to a very tight downwind and insufficient displacement for a base turn to the runway. The first officer continued to tell the captain what to do and when:

13:16:47.2 First officer: turn the autopilot off.

13:16:49.3 Cockpit Area Microphone: [sound similar to cavalry charge]

13:16:52.6 Cockpit Area Microphone: [sound of lever moving]

13:16:53.5 First officer: I'm gonna get your speed under control for you.

Source: CVR, pp. 57 - 64

At this point the aircraft was 44 knots above VREF (118 knots) and the report speculates that the first officer pulled the throttles to idle and selected full flaps without the captain’s knowledge.

13:16:56.2 Captain: oh I see the runway.

13:16:57.6 First officer: you can...

13:16:57.8 Captain: it's this one right?

13:16:58.4 First officer: yep you can start descending.

13:17:00.1 Captain: ‘kay full flaps.

13:17:02.2 First officer: you do have full flaps.

13:17:04.5 First officer: patience patience patience you got all the time in the world.

13:17:09.8 First officer: okay?

13:17:10.4 Captain: yes.

13:17:12.6 First officer: we don't wanna be on the news.

13:17:14.8 First officer: autothrottles have it.

Source: CVR, pp. 57 - 64

It appears the first officer reengaged the autothrottles after having pulled them to idle. There was at no point a positive change of aircraft control, but it appears the first officer was manipulating the throttles for a time.

13:17:17.8 First officer: you are looking very good my friend.

13:17:24.1 First officer: nice and relaxed...bring that turn around.

13:17:24.3 Cockpit Area Microphone: [sound similar to increase in engine rpm]

13:17:27.5 First officer: perfect.

13:17:30.2 First officer: it's okay...you got plenty of time.

13:17:33.6 First officer: let it keep comin' down though.

13:17:41.4 Cockpit Area Microphone: one thousand. [electronic voice]

13:17:42.7 First officer: did you? oh you turned the throttles off...

13:17:43.5 Cockpit Area Microphone: [sound similar to altitude alert]

13:17:44.4 Captain: yes.

13:17:44.6 First officer: (shoot/[expletive]).

Source: CVR, pp. 57 - 64

At this point the aircraft crossed the extended runway centerline.

13:17:46.4 First officer: let me see the airplane for a second.

13:17:51.6 Cockpit Area Microphone: [sound similar to decreasing engine rpm]

13:17:54.7 First officer: we're gonna go through it and come back okay?

13:17:56.8 Captain: okayyy...

13:18:00.4 Captain: it's here. [exclamation]

13:18:01.4 First officer: yes yes it's here but we are very high.

Source: CVR, pp. 57 - 64

The Flight Data Recorder indicated that one of the pilots deployed the flight spoilers. The airspeed was 135 knots, 17 knots above VREF. Seven seconds later the bank angle steepened, the stick shaker activated followed by the stick pusher.

13:18:03.6 Cockpit Area Microphone: sink rate. [electronic voice]

13:18:04.2 Cockpit Area Microphone: [sounds similar to stick shaker activation]

13:18:04.2 Captain: what are you doing?

13:18:04.2 Cockpit Area Microphone: pull up. [electronic voice]

13:18:04.5 First officer: ‘kay.

13:18:04.8 Captain: [Expletive].

13:18:04.9 Cockpit Area Microphone: [warbler sound consistent with stall warning]

13:18:05.0 First officer: no no no.

13:18:06.2 First officer: let-

13:18:06.5 Captain: what are you doing?

13:18:06.6 Cockpit Area Microphone:pull up. [electronic voice]

13:18:06.6 First officer: let me have the airplane.

13:18:07.3 First officer: let me have the airplane.

13:18:07.9 Cockpit Area Microphone: [sounds similar to stick shaker activation]

13:18:07.9 Cockpit Area Microphone: [warbler sound consistent with stall warning, continues throughout the end of the recording]

13:18:08.0 Cockpit Area Microphone: pull up. [electronic voice]

13:18:08.6 First officer: let me have the airplane.

13:18:09.4 Cockpit Area Microphone: pull up. [electronic voice]

13:18:09.7 Captain: oh. [exclamation]

13:18:10.0 First officer: oh [Expletive].

13:18:10.8 Hot Area Microphone [Expletive].

13:18:11.0 Cockpit Area Microphone: pull-- [electronic voice]

13:18:11.3 Cockpit Area Microphone: [sounds consistent with impact]

13:18:12.2 END OF TRANSCRIPT / END OF RECORDING

Source: CVR, pp. 57 - 64

5

The “What happened?” causes

The NTSB report notes that the lack of a proper approach briefing led to critical errors, including:

- flying the circling approach at a higher airspeed than the upper limit specified for the airplane’s category C approach category;

- failing to establish the airplane on the downwind leg of the circle-to-land approach; and

- failing to visually identify the runway early in the approach, likely due to obscuration by smoke.

Source: NTSB Report, WPR21FA286, p. 3

The report also notes that the aircraft’s FMS had 10 months earlier had a battery replacement which erased the correct aircraft empty weight which was never updated. In that time, the FMS had a weight 3,000 lbs. lower than actual, resulting in a 6 knot error when computing VREF.

The report suggest that it was the first officer who deployed the spoilers, further eroding any margin above the stall.

The combination of the FO’s improper deployment of the flight spoilers and the airplane’s bank angle and airspeed at the time resulted in the airplane exceeding the critical AOA, followed by an asymmetric stall (of the left wing), a rapid left roll, and impact with terrain.

The first officer’s (FO’s) improper decision to attempt to salvage an unstabilized approach by executing a steep left turn to realign the airplane with the runway centerline, and the captain’s failure to intervene after recognizing the FO’s erroneous action, while both ignored stall protection system warnings, which resulted in a left-wing stall and an impact with terrain. Contributing to the accident was the FO's improper deployment of the flight spoilers, which decreased the airplane's stall margin; the captain’s improper setup of the circling approach; and the flight crew’s self-induced pressure to perform and poor crew resource management, which degraded their decision-making.

Source: NTSB Report, WPR21FA286, p. 6

6

Circling myths

That is what happened – before we discuss why, we need to dispel some circling myths

Before we answer why, let’s cover three common circling myths.

Myth 1: Circling is just another thing we do

Reality check

Many airlines long ago realized circling approaches are needlessly dangerous and either banned them completely or tightly limited their use. They could do this because they had a limited number of airports, could lobby for and invest in added straight-in approaches, or could intensely train for whatever circling approaches were left. In the business jet world, we simply accept that circling approaches are a fact of life. We train for the generic (and relatively easy) approaches at KMEM and KJFK and assume these will qualify us to circle anywhere in the world.

Myth 2: Circling is a “visual maneuver”

We are often told in training that once you begin circling, you are executing a visual maneuver. That might be true semantically, that is by the pure definition of that word. But saying it is a visual maneuver doesn’t mean that it is as easy as a visual pattern entry. A circling maneuver often starts you in a location unlike any visual pattern, at a lower altitude, and closer than what would make for a comfortable visual pattern.

Reality check

Take, for example, a circling approach at Boire Field (KASH), New Hampshire, where the choices for the single runway were the ILS Runway 14 or the VOR Runway 32. I was based there for several years. If the ILS was down, your best option was said to be the VOR Runway 32, circle to Runway 14 with 2 sm minimum visibility. After flying simulated circling approaches with less visibility, I thought this would be easy. It was not: it left us rolling out just 1.2 nm from the touch down zone. That comes to (1.2)(318) = 382 feet. The runway has since been lengthened, but back then it was 5,500 feet long. We learned that given the choice of circling at minimums and landing someplace else, the someplace else was always a better option.

A VFR pattern entry to Nashua, by comparison, is easy. There is no terrain, the airport is easy to spot from a distance, and it was a simple matter to do a 45° pattern entry to a proper downwind. Can you turn a circling approach into a proper VFR pattern entry? If the weather permits: not only can you, but you should.

Myth 3: Circling is done at minimums

Every few years a business jet crashes during a circling approach and in most of these cases the pilots were flying too low and too close to the runway. As a result, they needed excessive bank angles or descent rates to make the “final” turn and lost control of their aircraft. The usual response is that we, the good pilots, would never do that. But you cannot blame these pilots alone, they were trained this way. I think if you were to ask many pilots that if they are cleared to circle at a random airport, they opt to fly at the Minimum Descent Altitude (MDA) and keep the aircraft within the visibility minimum shown on the approach chart. That is the only way they are permitted to do this during simulator training, so it is no wonder they do this in the airplane.

Reality check

What these pilots don’t understand is that a clearance to circle simply means, “visually maneuver your aircraft to land on that runway.” You can select whatever altitude you want, up to normally pattern altitude. Unless instructed otherwise, you can displace yourself as needed, as long as you keep in the airport traffic area. In fact, flying within the published visibility minimums might be against your Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs), if you want to fly a stable approach.

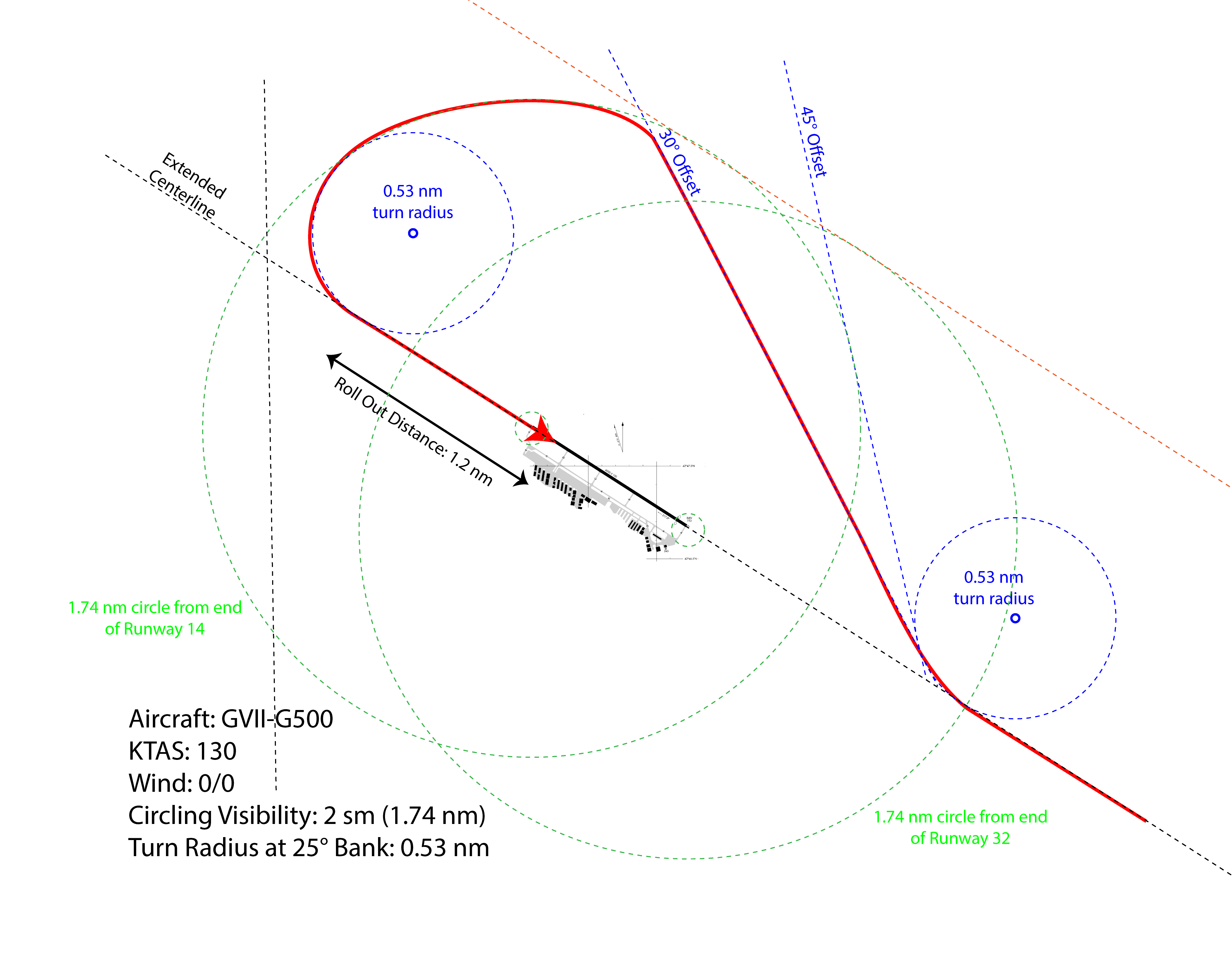

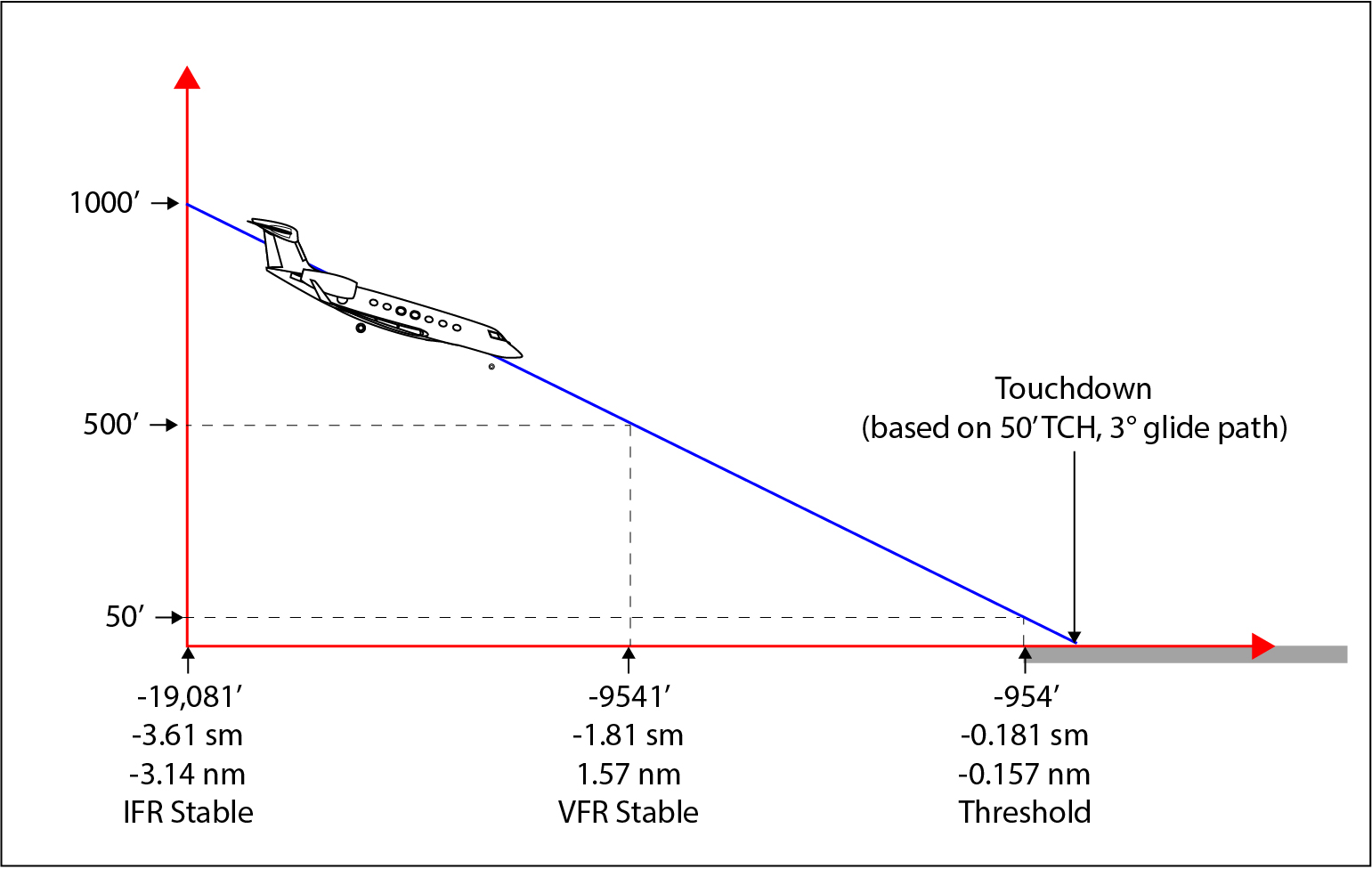

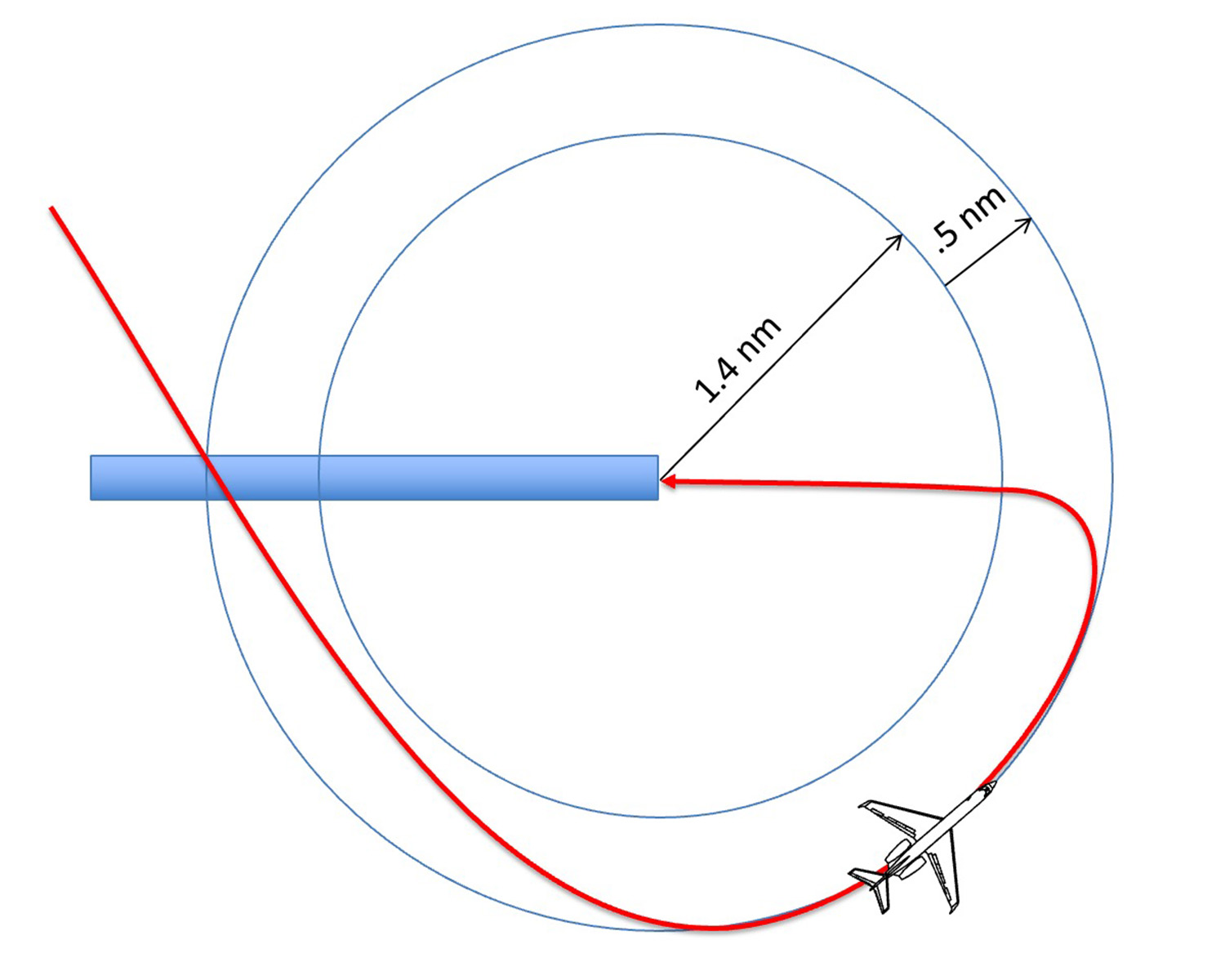

I am betting that you understand the need to be stable no later than 500 feet above the touchdown zone. Not only that, you say that you would go around if you are not on speed, on glide path, on extended centerline by 500 feet. At least that is what you tell your examiner during a check ride. As shown on the diagram, that means you need to be stable no later than 1.57 nautical miles from the touchdown zone, or 1.4 nautical miles from the end of the runway. Can you do that in a Category C aircraft with a typical visibility minimum of 1-3/4 sm (1.52 nm)?

If you are flying near sea level at 130 knots you will have a 0.53 nm turn radius. If you want the math:

Where V is True Airspeed in knots and θ is the bank angle in degrees. If you assume a 25° bank angle and use v = miles per minute:

The key point here is that it will take 1.9 nm to turn 90° onto final in time to roll out for a stable approach at 500’. Keep in mind that depends on you doing everything just right and the winds are calm.

Of course this begs the question: if I can’t maneuver within visibility minimums from the MDA and fly a stable approach, what am I supposed to do? Answer: go around, ask for a different approach, or divert!

7

But what caused this accident?

The NTSB correctly cites these pilots for an improper setup of the circling approach; they didn’t have adequate displacement with the runway. They also cite the crew for flying an unstable approach, not bothering to mention that the inadequate displacement caused the unstable approach. All that is what happened. But why did it happen?

In my view, that accident was caused by poor training which instilled in the pilots the idea that a circling approach can be flown without proper runway displacement and that wild maneuvering below stable approach height is acceptable. The simulator instructor will turn down the visibility to equal the minimums shown on the chart, so you have no choice but to fly an unrealistically tight approach. The simulator vendor will tell you their hands are tied under Part 142 but that isn’t true:

In order for the TCE to remain qualified to instruct/evaluate circling approaches, at published minimums, the TCE must be evaluated accomplishing the circling maneuver at published minimums during his/her proficiency check.

Source: [FAA Order 8900.1, Volume 3, Chapter 54,¶3-4355.C.3)a)3.

Notice the requirement is for the TCE (Training Center Examiner), not you, the person getting the examination. Your requirement is in the Airman Certification Standards:

Skills — The applicant demonstrates the ability to:

Keep the airport environment in sight and remain within the circling approach radius applicable to the approach category to a position from which a stabilized descent to landing can be made.

Make smooth, timely, and correct control application throughout the circling maneuver and maintain appropriate airspeed, ±5 knots. If applicable, maintain altitude +100/−0 feet, and desired heading/track, ±5°.

Source: FAA-S-AS-11, Task H, Landing from a Circling Approach, p. 49

Notice the criteria is the circling approach radius, not the visibility minimum. I don’t think this was a factor in this accident, but what is a factor is the mindset created by this kind of training. We are often checked at Memphis International (KMEM) where a Category C aircraft will have a visibility minimum of 1-1/2 sm (1.3 nm) but the allowed circling approach radius is 2.7 nm. We are required to fly the approach at the smaller visibility minimum for our check rides and left to wonder why we were unable to do this with a stable approach.

We are being checked to a higher standard than required, that’s good right? No, it teaches us the wrong procedures. You are taught only to circle at the MDA and very tight. Many of us take those lessons to heart and try to replicate that in the airplane. In the case of this Challenger crew, I can understand both pilots thinking the approach was salvageable all the way to the point where it wasn’t. They were killed by their training.

References

(Source material)

Air Traffic Control, Group Chairman’s Factual Report, WPR21FA286

Airline Transport Pilot and Type Rating for Airplane Airman Certification Standards, FAA-S-ACS-11, June 2019.

Aviation Investigation Final Report, WPR21FA286, Bombardier CL-600-2B16 (Challenger 605) N605TR, Loss of control in flight, Truckee, California, July 26, 2021.

Cockpit Voice Recorder (CVR), Group Chairman’s Factual Report, WPR21FA286

FAA Order 8900.1

Operational Factors, Group Chairman’s Factual Report, WPR21FA286