You may remember the headlines, of which there were many. My favorite: “Marine Corps called 911 to report missing F-35 jet in South Carolina.” News stories would be quick to point out each F-35B sets the U.S. taxpayer back $109 million but they were short on other specifics. Just over a year later, the official investigation results came out, heavily redacted. So, what happened, who gets the blame, was the pilot really at fault, and what lessons are there for the rest of us flying more conventional aircraft?

— James Albright

Updated:

2025-02-15

Date & Time: 17 September 2023, 1332 EDT

Aircraft: Lockheed Martin F-35B

Registration: 16-9591

Aircraft Fate: Destroyed

Injuries: 1 of 1 crew

Source: Command Investigation into the Circumstances Surrounding the F-35 Mishap of MAG-31, VMFAT-501 on 17 September 2023, United States Marine Corps, 2D Aircraft Wing, Chery Point, NC

Before we go any further, some English please. We often consider military aircraft “newness” by the letter attached to its designation. The B-52H, for examples, is newer than the B-52D. But that isn’t the case with the F-35:

F-35A – The U.S. Air Force version

F-35B – The U.S. Marine Corps version

F-35C – The U.S. Navy version

Of the three, the F-35B came out first.

CTOL – Conventional Takeoff / Landing mode

HMD – Helmet Mounted Display

HOOK/STOVL button refers to the landing arresting hook in the F-35C and the STOVL button in the F-35B.

JAGMAN – refers to the Manual of the Judge Advocate General, as in a publication, but is used in the report to refer to the investigators themselves.

MP – Mishap Pilot (His name was redacted in the beginning and replaced with MP later)

NATOPS – Naval Aviation Training and Operating Procedures Standardization

OCF – Out-of-Controlled-Flight

PCD – Panoramic Cockpit Display

SFD – Standby Flight Display

STOVL – Short Takeoff / Vertical Landing mode

VMFAT-501- Marine Fighter Attack Training Squadron 501, the USMC’s F-35B training squadron

3 — Was the pilot really at fault?

4 — Lessons learned for us flying more conventional aircraft?

1

What happened?

According to the report, the pilot was flying an Instrument Landing System (ILS) approach in Instrument Meteorological Conditions (IMC) into Joint Base Charleston. After he lowered the landing gear, he pressed the HOOK/STOVL button to change from conventional (Mode 1 CTOL) to short takeoff and vertical landing mode (Mode 4 STOVL).

A minute later, something (Redacted) caused malfunctions in several displays and communications systems, including the pilot’s Helmet Mounted Display (HMD). The Standby Flight Display (SFD) and communications remained functional. While considering his options, the HMD came back with “a multitude of cautions and advisories.” The pilot decided to continue the approach. Shortly after this, the HMD went out again and the pilot decided continuing the approach was not feasible and decided to retract the landing gear, initiate a conversion from Mode 4 STOVL to Mode 1 CTOL and execute a missed approach.

Upon climb-out, [the MP] discovered that he had lost communication with Charleston Tower and his wingman. Seconds later, his HMD returned accompanied by additional cautions and advisories. Additionally, he perceived the aircraft was not responding to pilot commands to convert out of Mode 4 (STOVL).

[The MP] then lost his HMD a third time at a last recalled altitude of 1,900 feet above ground level (AGL). With no visible reference to the horizon or ground, and unsure of which flight instruments he could trust, he perceived that the aircraft was still not responding to his commands to convert - and therefore was out-of-controlled flight (OCF). [The MP elected to eject in accordance with the F-35B Flight Manual OCF emergency procedures.

Source: Command Investigation Report, p. 3

The aircraft completed the conversion to CTOL and continued flying unmanned for 11 minutes.

2

Who gets the blame?

The JAGMAN investigation concludes that the mishap occurred as a result of pilot error, in that [the MP] incorrectly diagnosed an OCF flight emergency and ejected from a flyable aircraft – albeit under extremely challenging cognitive and flight conditions.

Source: Command Investigation Report, p. 3

The report redacted the pilot’s date of F-35 qualification, except they forgot to redact the year 2023, so he had at most nine months experience in the jet. He had 2,882.1 hours total flight time, of which 34.5 hours was in the F-35. Though his name was redacted from the report, Colonel Charles “Tre” Del Pizzo identified himself to the Marine Corps Times in a 2024 article. He is an accomplished Marine Aviator with 30 years of service, including combat tours. Most of his time appears to be in the AV-8 Harrier attack jet. As stated in the report:

Despite his extensive experience in AV-8B, MP is a relative novice in the F-35B.

Source: Command Investigation, p. 32

The pilot recalled that when he lost his HMD, he also lost the PCD and transitioned to the SFD.

The MP [Mishap Pilot] likely became disoriented due to the high cockpit workload coupled with the following factors:

- Lack of external visual cues due to IMC operations.

- Intermittent and recurring display failures.

- Head movements associated with switching between displays.

- Breakdown of flight instrument scan due to changing displays.

- Rapid assertions of Cautions and Advisories along with associated aural cues.

- Loss of primary communications.

- Possible vestibular illusions while transitioning from STOVL to CTOL.

Source: Command Investigation, p. 34

The pilot “perceived” the aircraft was not responding to his command to convert from STOVL to CTOL.

The F-35B Flight Manual states, “The aircraft is considered to be in out of controlled flight (OCF) when it fails to respond properly to pilot inputs.”

The F-35B Flight Manual, OCF Emergency Procedure (EP) Step *5A (memory item) is: “If out of control below 6000 feet AGL: EJECT.”

Source: Command Investigation, p. 19

The report then seems to contradict itself:

Per the definition of OCF in the F-35B Flight Manual, the MP applied an appropriate emergency procedure in response to a perceived loss of aircraft control below 6,000 feet AGL.

The F-35B Flight Manual definition for OCF is too broad and contributed to this mishap.

MP’s decision to eject was ultimately inappropriate, because commanded flight inputs were in-progress at the time of ejection, standby flight instrumentation was providing accurate data, and the MA’s backup radio was, at least partially, functional. Furthermore, the aircraft continued to fly for an extended period after ejection.

Source: Command Investigation, p. 34

3

Was the pilot really at fault?

Could the pilot have used the radios without the PCD?

MP experienced a failure of COM-A and COM-B. The Backup Radio was still functional; however, with a PCD failure, MP would have been unable to change frequencies via the PCD. The F-35B has radio knobs as an alternative; however, they are notoriously unreliable. Most pilots resort solely to changing frequencies via the PCD. This increases pilot workload and decreases situational awareness because pilots must access this feature via a drop-down menu which covers half of one portal. Changing frequencies this way is especially difficult in high workload situations such as when flying formation and/or in instrument meteorological conditions.

Source: Command Investigation, p. 37

Was the airplane really out of control?

The F-35B Flight Manual states, “The aircraft is considered to be in out of controlled flight (OCF) when it fails to respond properly to pilot inputs.”

Recommendation: VMFAT-501 should submit a NATOPS change modifying the definition of OCF to read, “The aircraft is considered to be in out of controlled flight (OCF) when it fails to respond properly to pilot pitch, roll, or yaw inputs.”

Source: Command Investigation, p. 37

Why did the HMD and PCD go out?

Unless it was redacted, the report doesn’t spend any effort into finding out why the pilot’s Helmet Mounted and Panoramic Cockpit Displays went out three times, or if such outages are common in the F-35. Part 2 of the Command Investigation Report is more redacted than not, but the conclusions reveal this:

The EDU [Electrical Distribution Unit] contactor output to the Nacelle Fan tripped at AC time 4751.01s (17:32:05.5Z) due to an overcurrent event causing a transient voltage drop on the ICC1 [Inverter Converter Controller] voltage output.

Source: Command Investigation, Part 2, p. 72

And this was followed by several statements of things working properly, remaining powered, and working as expected and nominally. But the HMD and PCD did not work nominally. They are very lucky this airplane didn’t end up in a populated area. This would seem to be a problem worth grounding the fleet over until they figure it out.

Is this a “one off” problem or systemic? According to multiple sources, it is systemic. For example:

The F-35A fleet was supposed to achieve a rate of 20 Mean Flight Hours Between Critical Failures after 75,000 fleet hours. But in 2023, it only achieved a rate of 10.5, despite having racked up more than 288,000 total flight hours since entering service. The F-35B variant, operated by the Marines, and the F-35C, flown by the Navy, both missed their goals as well.

Source: John A. Tirpak, Air & Space Forces Magazine, Feb 8, 2024

Imagine flying an airplane that has a “critical failure” every 10 hours. Then imagine it is equipped with a backup radio that is “notoriously unreliable.”

On the one hand: “When in doubt, get out”

So, using the report’s words, the pilot applied an appropriate procedure [to eject] but that his decision to eject was ultimately inappropriate. There are many in the single-seat fighter pilot community who believe, “when in doubt, get out,” and “when it hits the fan, give the airplane back to the taxpayer.” Many can give more than a few names of comrades who delayed a second before attempting to eject, and that second cost them their lives. Yes, I see those points as valid. But do those points apply in this situation?

On the other hand: Situational Awareness (SA)

Most of us understand intuitively what “out of controlled flight” means: the aircraft’s attitude is unaffected by your control inputs. Few of us appreciate the intricacies of going from Conventional Takeoff and Landing (CTOL) to Short Takeoff Vertical Landing (STOVL) modes. I know it may be a stretch but let me use as a corollary a conventional aircraft’s flap system. You move the flap handle, and nothing happens. Are you in out-of-control flight? In this F-35 accident, the pilot selected CTOL mode and things didn’t appear to be headed in that direction. He lost his HMD and PCD and had to rely on his SFD, which he didn’t trust. In my view, he should have been able to crosscheck the SFD against the altimeter and airspeed indicator and understand the SFD was providing valid attitude information. He should have realized he was not in an out-of-control dive and he should have given the CTOL a little more time before punching out. The report tells us this much, but this is what happened, not why.

I think the why involves aircraft design (blame the acquisition process), the failure to ground the fleet (blame the military’s command hierarchy), and the failure to train pilots to deal with these problems. The pilot didn’t know if he could trust the Standby Flight Display. He should have been trained to do so. And that leads us to . . .

4

Lessons learned for us flying more conventional aircraft

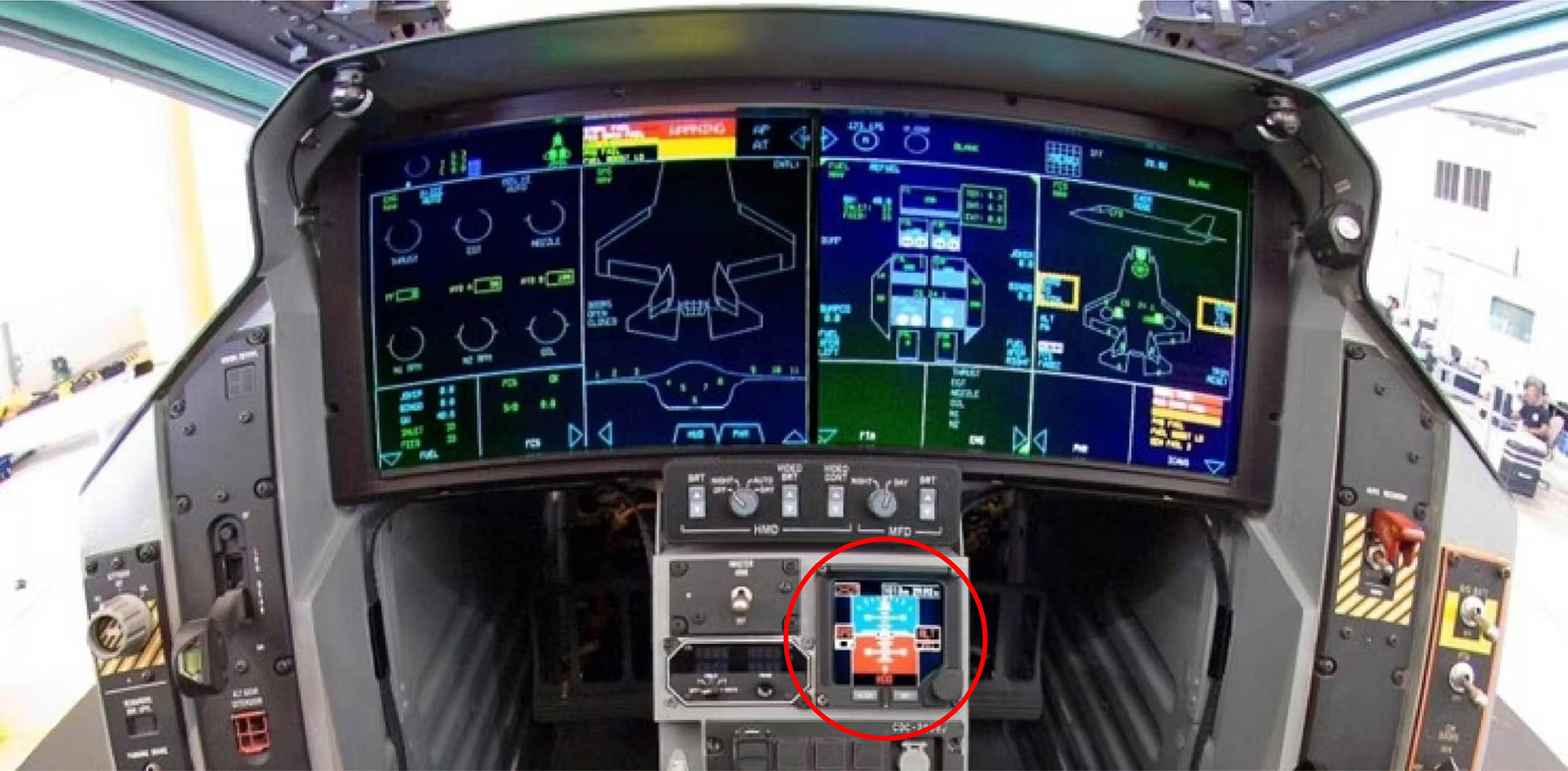

Here is a look at the Panoramic Cockpit Display:

Going from this to the SFD can’t be fun, but the F-35’s SFD isn’t that bad:

There are problems, however. First, you are looking low in the cockpit at a smaller screen with less information presented than you are used to. Second, you may not have ever flown an approach to minimums using the SFD. Believe it or not, some business jets are in even worse shape when it comes to flying off a standby instrument.

In this photo you can see part of the SFD just ahead and below my right hand while flying a visual approach in our Gulfstream G450. We had to demonstrate an approach to minimums using this SFD regularly. The SFD is low and to the pilot’s right. It can be a challenge unless you practice often. It was a challenge, that is, until we learned how to cheat. By placing an Ipad with the camera app running right in front of the small SFD, we got a large SFD:

The gear had to be down and a cloth used to balance it just right. An even better solution was to upgrade to a Gulfstream GVII:

Each pilot got their own, larger SFD and they were placed higher on the glareshield, close to the normal field of view. Approaches to minimums with this SFD are much easier, but still took practice. And that leads us to the lesson learned from the loss of this F-35 that applies to all pilots, military and civilian:

Understand your aircraft’s known issues and train to deal with them. Practice using standby systems in a simulator until you are proficient.

References

(Source material)

Command Investigation into the Circumstances Surrounding the F-35 Mishap of MAG-31, VMFAT-501 on 17 September 2023, United States Marine Corps, 2D Aircraft Wing, Chery Point, NC.

John A. Tirpak, Air & Space Forces Magazine, Feb 8, 2024