If you've never heard the term "instantaneous wind," chances are you've never flown out of Aspen. The first time I heard of it was at Aspen and it made me laugh. We used to joke about "taking off between the gusts," but it was a joke. The pressure to takeoff no matter the winds or weather can be too much for some pilots. They should take heed of another saying, "you are paid to say no."

— James Albright

Updated:

2024-07-29

Accident airplane following runway excursion,

CEN22LA130, Figure 1.

The NTSB implies that the pilots never reached VR because of the magnitude of the tailwind, but ignored the fact that, according to the CVR, the SIC did call "rotate." The crew was blamed for taking off with a tailwind that exceeded their aircraft limitations, and that is a good call. But the tower should also have been cited for offering "instantaneous winds" of what I consider dubious value (more on that later) when these were not requested by the crew. The crew was led down the "prim rose path" by the tower. Was the crew at fault? Absolutely. But the NTSB missed a chance to fix what is broken in the Aspen Tower SOP manual. I suspect the tower is encouraged to get aircraft off the ramp. You should see a pattern in the way winds are called for takeoff aircraft versus landing aircraft.

None of this excuses the pilots. If tower, your passengers, or your fellow pilots ever talk you into using "instantaneous winds," you should consider the story Cluedo! It is a military term akin to "Nordo" which literally means "No Radio," but can be read, "radio-less." If you are cluedo, well, you know.

Note: If you have flown into Aspen since this accident, please use the "Contact" button on the bottom of the page and let me know if tower is still using "instantaneous" wind calls.

1

Accident report

- Date: 21 Feb 2022

- Time: 11:33

- Type: Raytheon Hawker 800XP

- Operator: Roper Aviation LLC

- Registration: N99AP

- Fatalities: 0 of 2 crew, 0 of 4 passengers

- Aircraft Fate: Substantially damaged

- Phase: Takeoff

- Airport: (Departure) Aspen-Pitkin County Airport, CO (KASE)

- Airport: (Destination) Austin-Bergstrom International Airport, TX (KAUS)

2

Narrative

On February 21, 2022, at 1133 mountain daylight time, a Raytheon Aircraft Company Hawker 800XP airplane, N99AP, was substantially damaged when it was involved in an accident at Aspen-Pitkin County Airport (ASE), Aspen, Colorado. The two pilots and four passengers were not injured. The airplane was being operated as a Title 14 Code of Federal Regulations Part 91 business flight.

According to the flight crew reports and the cockpit voice recorder (CVR) audio, prior to departure, the airplane and runway were clear of any contaminants, and all pre-takeoff checks were normal. At 1102:46, the airplane was cleared to taxi to runway 33 with automatic terminal information service (ATIS) information Bravo. The ATIS indicated that the wind was from 170° at 18 knots (kts) and gusting to 30 kts. During taxi, the flight crew changed the takeoff flaps from 0° to 15° to reduce the takeoff length by 800 ft per the crew’s Aircraft Performance Group calculations, and the first officer entered the new airspeeds in the flight management system.

About 1119, the ASE air traffic control (ATC) tower controller informed the flight crew the takeoff would be delayed due to arriving traffic. At 1131:54, the controller provided the takeoff clearance for runway 33 and reported the wind was from 160° at 16 kts, gusting to 25 kts. In addition, the controller provided the “instantaneous” wind, which was from 180° at 10 kts. The captain reported that “at takeoff clearance, constant winds were reported by tower at [180° at 10 kts] which was within aircraft maximum tailwind takeoff limitation.”

According to CVR audio, the takeoff was initiated at 1132:26. The captain performed a static takeoff, and the first officer made all the callouts: airspeed alive, 80 kts, takeoff decision speed (V1) at 111 kts, and rotate (VR) at 121 kts. The captain reported that, at VR, he applied back pressure on the yoke; however, the airplane would not become airborne. The captain reported, “the yoke did not have any air resistance or any pressure on it as we experience normally in Hawkers (the weight and pressure on the yoke felt the same as though…the airplane was stationary on [the] ground).”

After a few seconds without any indication the airplane would take off, the captain called for and performed an aborted takeoff by reducing the engines to idle, deploying the thrust reversers, and applying the brakes. The airplane subsequently departed the end of the runway into the snow. The captain secured the airplane and assisted in the evacuation of the passengers.

Source: CEN22LA130, p. 3

The NTSB report on the Cockpit Voice Recorder (CVR) doesn't include verbatim transcriptions of what is said by the pilots and heard on the radio, only summaries. The terms "continous" and "instantaneous" are used once each to describe the winds. Because the final report only uses "instantaenous" and does that 15 times, I am going to assume to CVR report's use of "continuous" should read "instantaenous."

11:13:17 — [Aspen tower cleared a different aircraft for takeoff on runway 33 and reported the winds as 170 at 15, gust 11, continuous 160 at 10.]

11:16:46 — [Aspen tower cleared a different aircraft to land on runway 15 and reported the winds as 160 at 15, gust 22.]

11:18:33 — [Aspen tower cleared a different aircraft to land on runway 15 and reported the winds as 160 at 15, gust 22.]

11:18:54 — The Aspen tower controller indicated to the flight crew that it would be about 15 minutes before they could depart due to a bank of incoming arrivals.

11:20:59 — [Aspen tower cleared a different aircraft to land on runway 15 and reported the winds as 170 at 15, gust 24.]

11:25:23 — [Aspen tower cleared a different aircraft to land on runway 15 and reported the winds as 160 at 11, gust 24.]

11:31:23 — The Aspen tower controller cleared the aircraft to line up and wait.

11:31:54 — The Aspen tower controller cleared the aircraft for takeoff on runway 33. The controller reported the winds as 160 at 16, gust 25, and instantaneous wind 180 at 10. The flight crew acknowledged the takeoff clearance.

11:32:00 — The PIC indicated to the SIC that he would be performing a static takeoff.

11:32:26 — Sounds similar to engine thrust increasing were noted.

11:32:30 — The PIC indicated that takeoff power had been set. The SIC stated that he was arming APR.

11:32:38 — The SIC commented that airspeed was alive.

11:32:47 — The SIC called out 80 knots.

11:32:54 — The SIC called out V1.

11:32:58 — The SIC called out rotate.

11:33:05 — Sounds similar to engine thrust decreasing were noted.

11:33:09 — The PIC indicated he was aborting takeoff and asked the SIC to inform the tower controller.

11:33:10 — The SIC informed the tower controller they were aborting takeoff.

11:33:15 — Sounds similar to the aircraft departing the paved surface were noted. The recording ended shortly thereafter. [End of recording.]

Source: CEN22LA130, CVR

Notice that the two aircraft given takeoff clearances were given "instantaneous" or continuous" winds at 10 knots. The 11:13:17 CVR doesn't make sense: how can a wind gust from 15 to 11. Notice that all the landing aircraft were given the actual winds without an "instantaneous" or "continuous" call.

3

Analysis

The flight crew of the business jet was conducting a cross-country flight. Before departure, the airplane and runway were clear of any contaminants, all pre-takeoff checks were normal, and the flaps were set to 15° to reduce the takeoff length. At the time the airplane was cleared to taxi to the departure runway, the reported wind was from 170° at 18 knots (kts) and gusting to 30 kts. This wind report represented a prevailing tailwind that exceeded the airplane’s takeoff and landing maximum tailwind limitation, which was 10 kts. About 30 minutes later due to arrival traffic, air traffic control (ATC) provided the takeoff clearance and reported the wind was from 160° at 16 kts, gusting to 25 kts, and the “instantaneous wind” was from 180° at 10 kts. Following the accident, the captain reported that “at takeoff clearance; constant winds were reported by tower at [180° at 10 kts] which was within aircraft maximum tailwind takeoff limitation.”

About 30 seconds after receiving the takeoff clearance and the current wind report from ATC, the captain performed a static takeoff, which began at the end of the runway, and the first officer made all the callouts. According to the captain, at rotation speed (VR), he applied back pressure on the yoke; however, the airplane would not become airborne. After a few seconds without any indication the airplane would take off, the captain called for and performed an aborted the takeoff. The captain reduced the engines to idle, deployed the thrust reversers, and applied the brakes. The airplane subsequently departed the end of he runway into the snow and sustained substantial damage to the right wing and fuselage.

Because postaccident examination of the airplane and flight control system found no anomalies, and findings from an airplane performance study indicate that the airplane should have been able to rotate once it reached the reported VR, it is very likely that the airspeed did not reach VR due to tailwind conditions that exceeded the airplane’s maximum tailwind limitation. The airplane was not equipped with a flight data recorder or any additional data sources that could have captured or reported the airplane’s airspeed during the attempted takeoff.

Source: CEN22LA130, pp. 1- 2

The "it is very likely that the airspeed did not reach VR" phrase is a polite way for the NTSB to say the pilots lied. Reading the CVR summary shows that the SIC did call "Rotate."

Although the flight crew received an unsolicited instantaneous wind report from ATC that was at the airplane’s maximum allowable tailwind component of 10 kts, multiple wind reports for 30 minutes before the attempted takeoff were significantly above the tailwind limitation. The flight crew failed to consider the wind conditions that were consistently above the maximum tailwind limitation and decided to attempt the takeoff once they received an instantaneous wind report that did not exceed the tailwind limitation. Per the flight crew statements, they interpreted the instantaneous wind reported by ATC just before takeoff as the constant wind conditions.

The term ”instantaneous wind” is used by the airport’s ATC tower and is not defined in any Federal Aviation Administration publication. Because the ambiguous term is not defined in available resources, pilots that infrequently operate at that airport are likely not familiar with the definition and potential operational impact.

Source: CEN22LA130, pp. 1 - 2

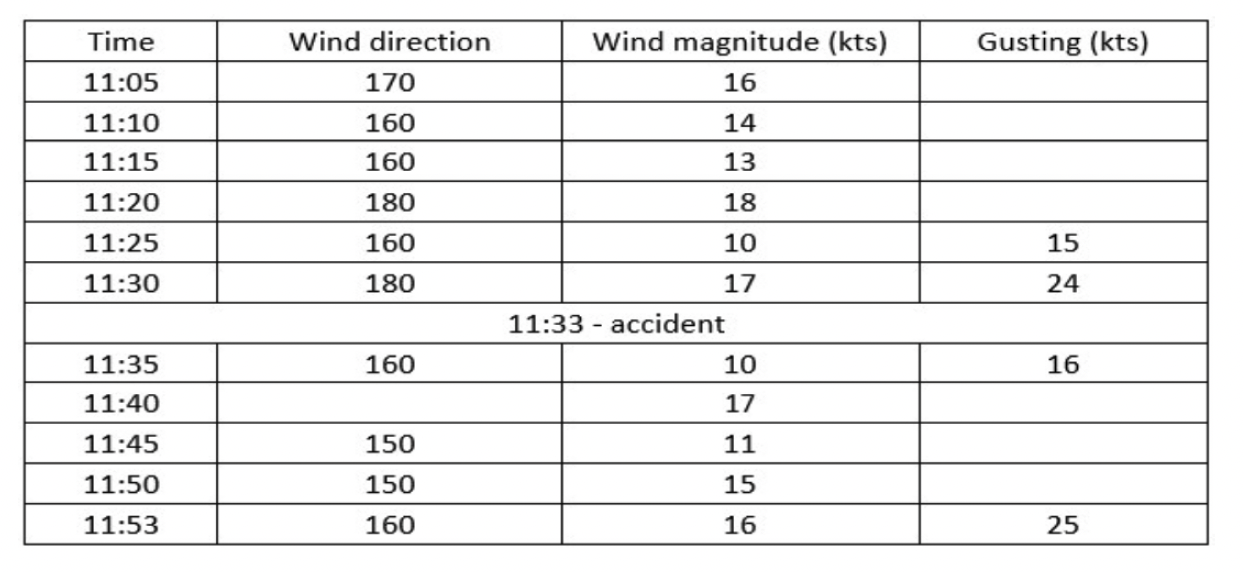

Winds from automated ASE weather station, CEN22LA130, Table 1

ASE ATC is serviced as a level 6 combined control facility, which is defined as an ATC facility that provides approach control services for one or more airports as well as en route air traffic control (center control) for a large area of airspace. Some facilities may provide tower services along with approach control and en route services.

ASE is equipped with multiple windsocks, an automated surface observing system (ASOS) (maintained by the National Weather Service) and a standalone weather sensor (SAWS) (maintained by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) Technical Operations), which are located about 20 ft from each other on the north side of taxiway A1.

Source: CEN22LA130, p. 8

The FAA ASE airport traffic control tower Standard Operating Procedures (SOP), section 1-11 Official Weather, states in part:

c. Wind.

- The SAWS Two-Minute Average Wind is defined as the Official Wind and must be given to all aircraft in lieu of any other wind information.

- The SAWS Two-Minute Average Wind may be supplemented with other information (i.e., the SAWS Instantaneous Wind or the ASOS Two-Minute Average Wind) in the judgment of the controller.

- If a pilot requests, the instantaneous wind may be issued after the SAWS Two-Minute Average Wind has been given.

- When the wind is above a 10-knot sustained tailwind or gusting above a 15-knot tailwind between headings 280°-020° for Runway 15 or headings 100°-200° for Runway 33, one of the following statements must be announced on all frequencies and included in the ATIS broadcast:

- Either statement may be utilized individually or combined if needed in the judgment of the controller.

- Wind statements on the ATIS should be placed after the weather sequence, and prior to the Notices to Airmen (NOTAMs).

(a) “USE CAUTION, (affected runway) STRONG TAILWIND CONDITIONS EXIST.”

(b) “USE CAUTION, RAPIDLY CHANGING TAILWIND CONDITIONS EXIST.”

"Instantaneous wind" is a term used by ASE that is not defined in any FAA publication of record. After the accident, the ASE ATM was asked why ASE ATC chose to use the phrase “instantaneous wind” when reporting the standalone weather, the manager stated he was not sure where that [term] had originated. He reported that a few operators routinely request the instantaneous wind reports because of their familiarity with ASE operations, but other operators and general aviation pilots may not be aware of instantaneous wind reports or the definition of the term. In addition, as specified in the ASE SOPs, the instantaneous wind report is only supposed to be provided when requested.

Source: CEN22LA130, pp. 9 - 10

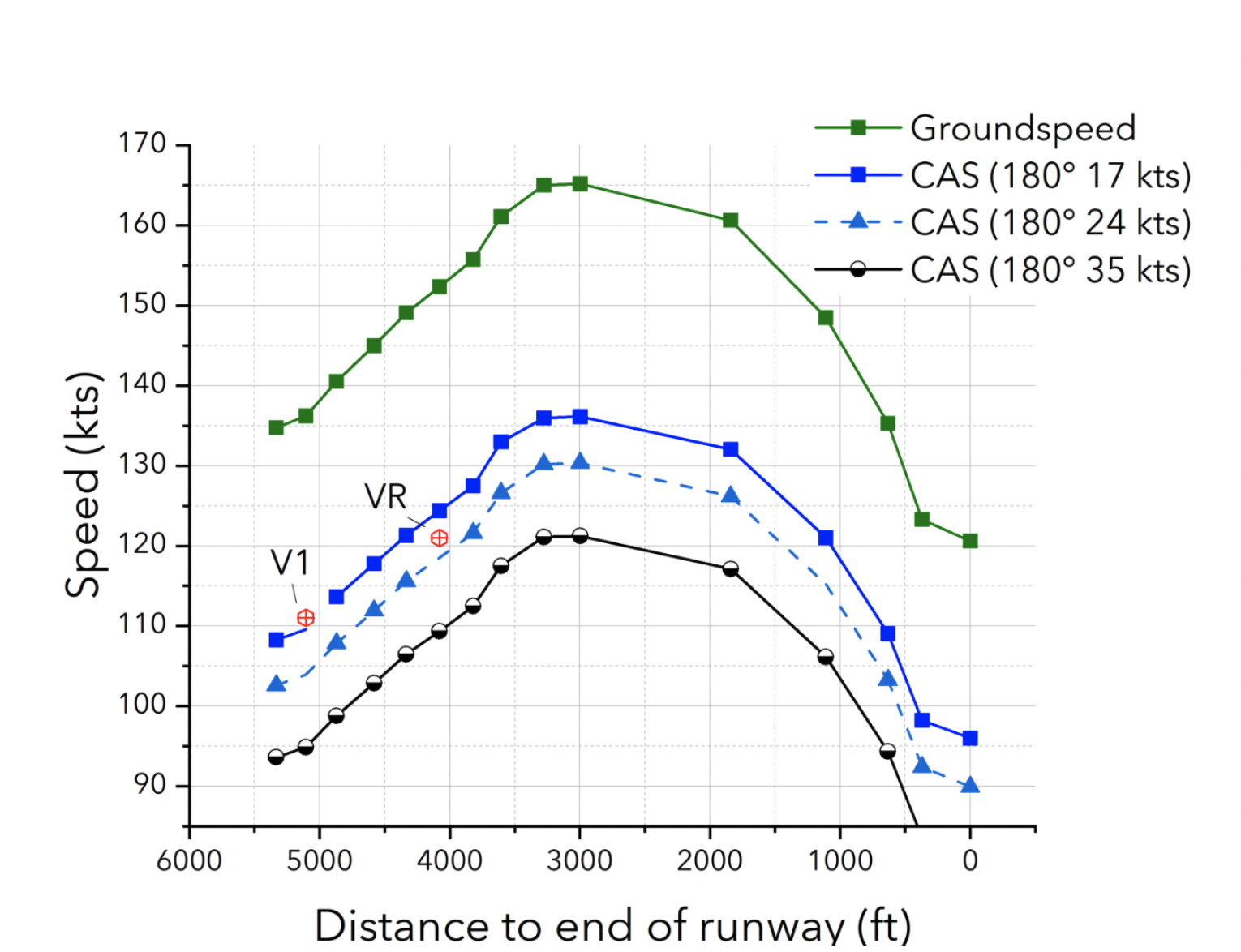

Calculated CAS for three different wind conditions, CEN22LA130, figure 5

At VR, the airplane’s pitch control authority should have been sufficient to raise the airplane’s nose and begin liftoff. However, the flight crew reported that the airplane did not rotate. This could imply that when the pilot pulled back on the yoke, that the airplane’s airspeed was insufficient to induce rotation.

The black line in Figure 5 shows the calculated CAS for 35 kt wind from 180°. At the maximum achieved ground speed of 165 kts, a wind of this magnitude would lower the airplane’s indicated airspeed to just below VR. Title 14 Code of Federal Regulations Part 25.107, Takeoff Speeds, requires that the VR be at least 10% greater than the minimum calibrated airspeed at which the airplane can safely rotate and lift off.

Therefore, for a reported VR of 121 kts, the airplane should have lifted off after reaching an airspeed of 110 kts. A 35-kt wind would not reduce the maximum achieved ground speed of 165 kts sufficiently to prevent the airplane from flying, and thus after achieving V1 (111 kts), the flight crew should have had sufficient air load to rotate the airplane. This was not consistent with the flight crew account that the yoke did not have any air resistance when the yoke was pulled back, considering that the wreckage examination revealed no discrepancies with flight control continuity to the elevator system. Even if a tailwind increased to more than the maximum reported gusting of 25 kts after VR or if the flight crew call to rotate was made before VR was achieved, the airplane’s airspeed should have resulted in noticeable air resistance when the yoke was pulled back. These discrepancies could not be resolved with the available evidence.

Source: CEN22LA130, pp. 16 - 17

The NTSB assumes that because the aircraft's flight controls were operating normally when examined, they assumed the flight controls were operating normally after lining up on the runway with a strong tailwind. Did the change in flap setting from 0 to 15 during taxi require a change in takeoff trim that the crew failed to make? We don't know, the NTSB didn't mention that. Could there have been a temporary problem caused by this situation? We don't know. The NTSB didn't investigate. It could very well be that the yoke would have reacted normally, but we don't know. The lack of a Flight Data Recorder allows us (and the NTSB) to speculate.

4

Cause

The National Transportation Safety Board determines the probable cause(s) of this accident to be: The flight crew’s decision to takeoff in tailwind conditions that were consistently above the airplane’s tailwind limitation, which resulted in a runway overrun following an aborted takeoff. Contributing was the flight crew’s use of the instantaneous wind report for the decision to attempt the takeoff.

Source: CEN22LA130, p. 2

I would change the last sentence in the probable cause statement to the following:

The Aspen Tower's practice of giving instantanous winds to aircraft prior to takeoff creates cockpit confusion, invites poor decision making, and was a crucial link in the chain of events that led to this runway excursion.

References

(Source material)

Aviation Investigation Final Report, CEN22LA130, National Transportation Safety Board, last revision date June 24, 2024.

Specialist's Factual Report of Investigation, CDN22LA130, Cockpit Voice Recorder, May 10, 2022