A captain returning from a six year absence was only too happy to cede his authority to a first officer who was happy to take it. Another crew willing to takeoff below minimums because tower called the mins lower than they were. A tower controller who decided he didn't need to warn the airplane on takeoff roll that there was another airplane lost on a runway. In the words on an NTSB investigator: "There are really just no heroes in this."

— James Albright

Updated:

2025-10-15

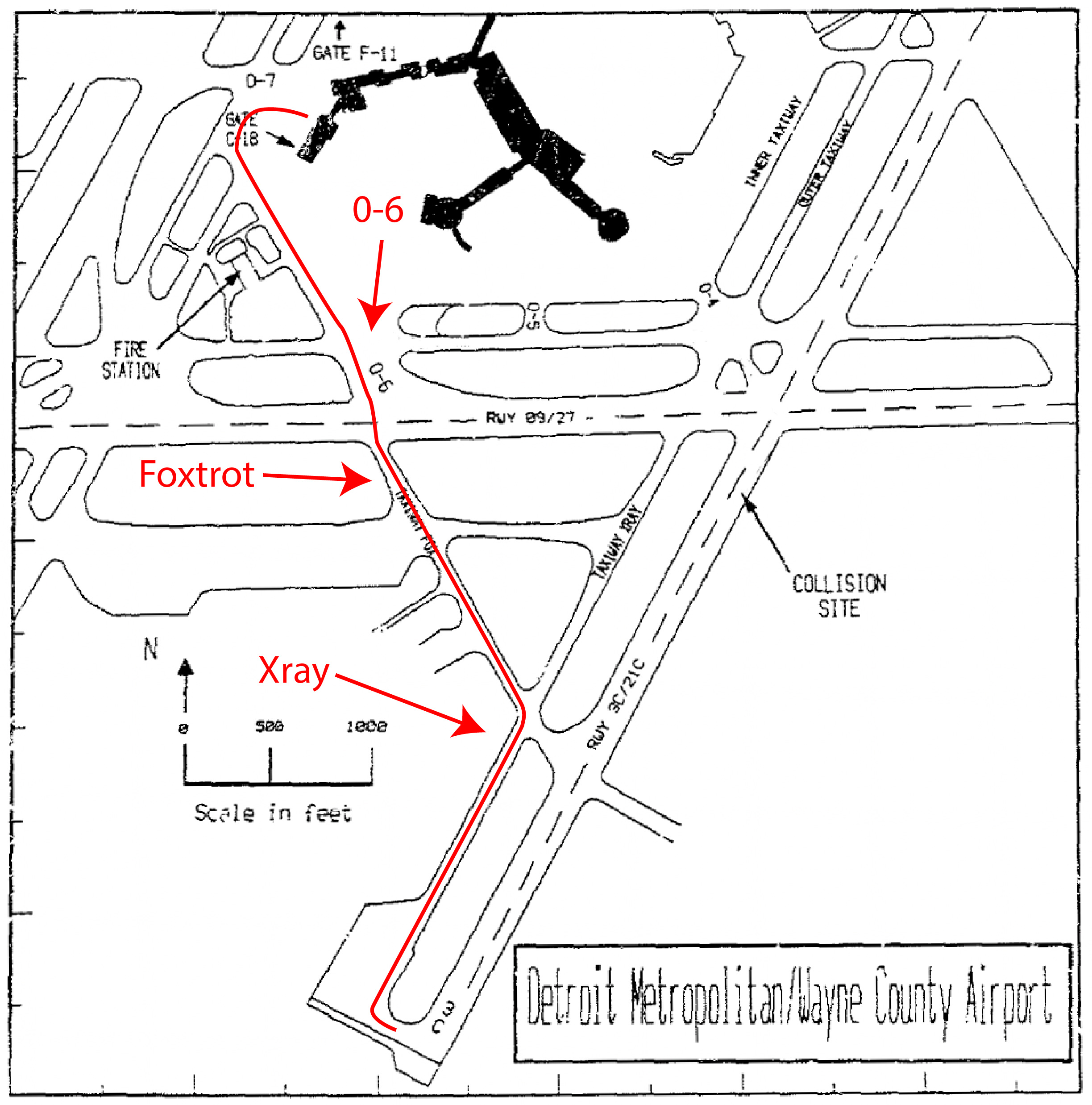

On December 3, 1990, Northwest Airlines (NWA) Flight 299 was a Boeing 727 scheduled to depart Detroit Metropolitan Wayne County Airport (KDTW), Michigan, bound for Memphis, Tennessee. It was pushed back for taxi around 1331. The visibility was reported by the Automatic Terminal Information Service (ATIS) as ¾ mile. Their clearance was to taxi to runway 3C via Oscar 6, to Foxtrot taxiway, and to advise the east ground controller when crossing runway 9/27. As they made their way to runway 3C, they attained a new ATIS which reported the visibility had dropped to ¼ mile. They also caught sight of a taxiing NWA DC-9, apparently going someplace else on the airport. [AAR-91/05, p. 4]

That DC-9 was NWA Flight 1482, bound for Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, with a crew that requires some discussion to really understand what was about to unfold.

Date: December 3, 1990

Time: 13:45

Location: Detroit-Metropolitan Wayne County Airport, MI (KDTW)

Aircraft One

Operator: Northwest Airlines

Type: Douglas DC-9-14

Registration: B3313K

Fatalities: 8 / 44 Occupants

Aircraft damage: Destroyed

Aircraft Two

Operator: Northwest Airlines

Type: Boeing 727-251

Registration: N278US

Fatalities: 0 / 154 Occupants

Aircraft damage: Substantial, repaired

1

The crew of the DC-9

The captain

This flight was to be the captain’s first without supervision after an extended period off flying status. The 52-year-old captain just returned from 6 years of medical leave due to kidney stones. He started his airline career with Pacific Airlines in 1966, which merged with Hughes Airwest, which was acquired by Republic Airlines. During his medical leave, Republic was bought out by Northwest Airlines. Because he had been gone so long, he had to repeat DC-9 initial and an Initial Operating Experience (IOE) trip with a check airman, which he successfully passed on November 30, 1990. He had over 23,000 total hours, over 4,000 in type. He had never attended Crew Resource Management (CRM) training, as NWA did not have a CRM program at the time. [AAR-91/05, pp. 12-13]

On returning to NWA after his medical leave, the captain was in an unfamiliar environment of new manuals, checklists, and procedures, resulting from the airline mergers that occurred during this absence. He was an experienced captain but, because of his 6-year layoff, he may not have had full confidence in his ability to carry out some of his line flying duties. Thus, on the evening before the flight, he spent time trying to thoroughly familiarize himself with his trip sequence route, and possible instrument approaches to be flown. Also, before the accident flight, he spent a considerable amount of time briefing the first officer on expected procedures during the proposed trip sequence. The captain clearly attempted to include the first officer in the conduct of the flight. However, there is no evidence that the captain studied the airport layout or discussed it with the first officer before they began to taxi.

[AAR-91/05, p. 52]

The first officer

The 43-year-old first officer recently retired from the Air Force, having flown B-52s and T-38s, with instructor pilot time in both. He was hired by NWA seven months earlier, had accumulated 185 hours in the DC-9, and was still on probation. [AAR-91/05, p. 13] He had a lot of “command experience” in the Air Force, and that command experience was more recent than the captain’s.

While waiting for the passengers to board, the captain asked the first officer if he was experienced with DTW operations. The first officer said yes, which wasn’t true. He explained in post-accident testimony that he meant he knew about the radio changeover points, not that he was familiar with the airport layout. But it became obvious that the captain thought his first officer was very familiar with the airport layout.

While discussing the possibility of icing, the first officer said, “I’ve always flown with an ejection seat. Used it twice.” The captain asked if it was scary, to which the first officer said, “I got shot down once over in Southeast Asia . . . I didn’t have time to get scared.” The first officer added, “I retired as a lieutenant colonel.” These were all lies: he had never ejected from an airplane, wasn’t shot down, and he retired as a major. The captain took him at his word, however, and seemed to be impressed by his first officer.

A comparison of the first officer's military records and the CVR recording revealed that statements he made to the captain prior to pushback concerning his military accomplishments were exaggerated. However, his military records did confirm that he was an experienced B-52 aircraft commander and instructor pilot, accustomed to leading an aircrew of six people through some demanding flying situations.

The falsehoods that the first officer told the captain possibly affected the captain's opinion of the first officer's capabilities relative to his own. At the time the conversations took place, the pilots were probably still assessing each other's overall ability to perform the tasks necessary to complete the flight. These conversations led to a unique command/leadership situation. As a result, the captain could have become overly impressed by the capabilities of his first officer. A significant example of the first officer's tendency to embellish his stature in the eye of the captain was the first officer's indication that he was familiar the DTW airport.

The Safety Board believes that the first officer's exaggerations about his knowledge of DTW operations, and the distortions of his military flight experiences and career achievements, demonstrated a lack of professionalism on his part. The Safety Board believes that ethical conduct among professional flight crewmembers dictates that they provide accurate information about themselves. Such information is crucial to the performance of professional activities, particularly in situations where crewmembers are meeting and flying together for the first time--situations that are not uncommon in current airline operations. Consequently, under such circumstances, the Safety Board believes that to deliberately provide less than accurate information about one's flight experiences and career achievements is inimical to flight safety.

[AAR-91/05, pp. 52-53]

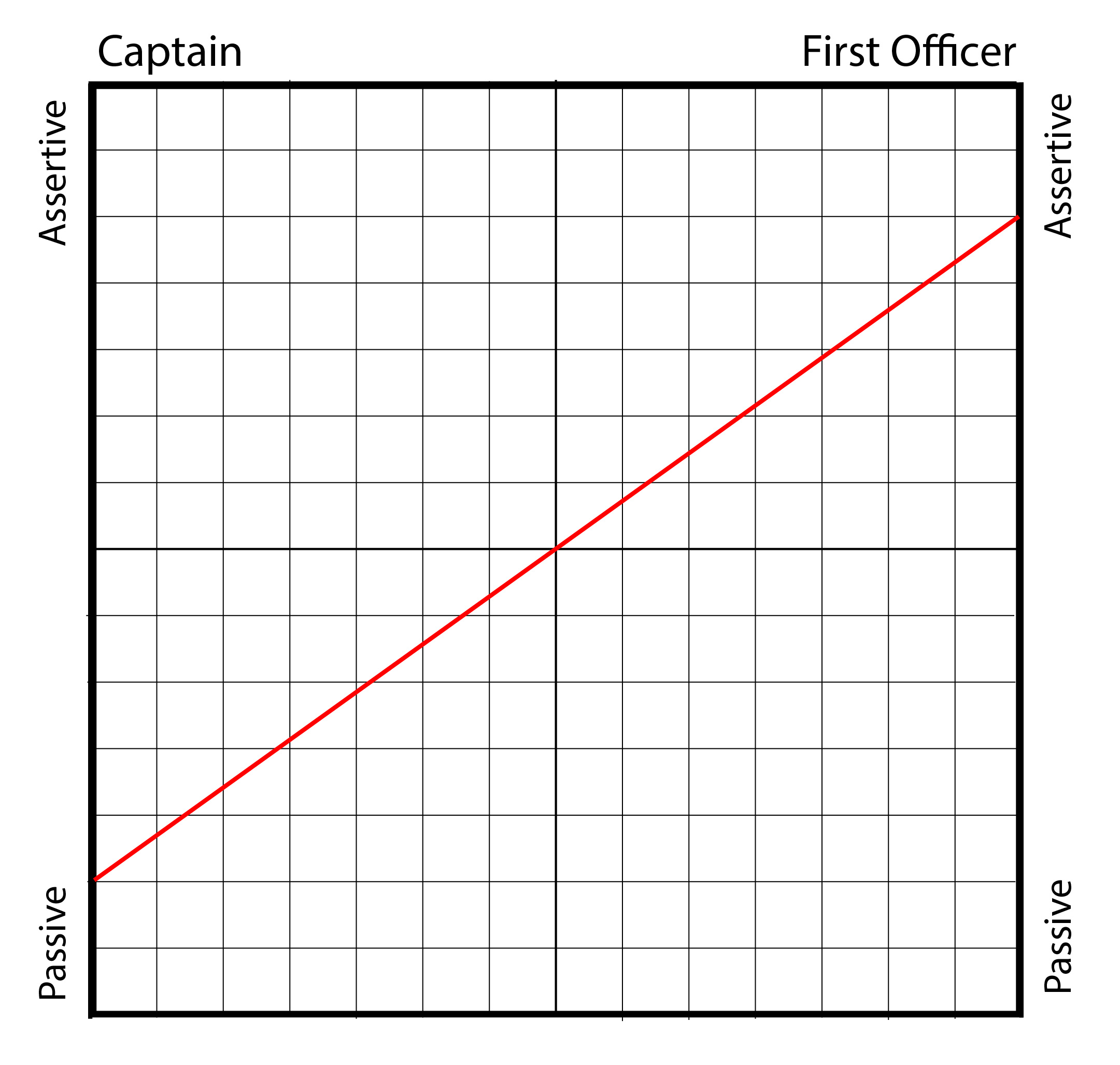

An inverted authority gradient

Though the NTSB report doesn’t use “authority gradient” in describing the relationship between the captain and first officer – using “role reversal” instead – they describe what was later known to be an “inverted authority gradient.” We’ll summarize what the accident report says, and then quickly explain the authority gradient concept.

The Safety Board believes that a nearly complete and unintentional reversal of command roles took place in the cockpit of the DC-9 shortly after taxiing began. The result was that the captain became overly reliant on the first officer. The captain essentially acquiesced to the first officer's assumption of leadership. This role reversal contributed significantly to the eventual runway incursion.

[AAR-91/05, p. 53]

This is a good example of an inverted authority gradient, which begs for an explanation about what that is.

An authority gradient refers to the perceived or actual difference in power, status, or authority between individuals in a hierarchy. This gradient influences how the team members communicate and how decisions are made. An optimal authority gradient is when the captain is more assertive than the first officer, but not so assertive as to completely shut down the first officer. This gradient makes it clear that the captain is in charge, but that the first officer’s voice will be heard when the situation allows.

A steep authority gradient happens when the captain refuses to entertain any objections from the first officer.

An inverted authority gradient happens when the first officer usurps the captain’s authority by being more assertive than the captain.

For more about this: Authority Gradient.

2

Lost in the fog

At 1335, the DC-9 was cleared to taxi by the west ground controller: “1482 right turn out of parking taxi runway 3C exit ramp at Oscar 6 contact ground now 119.45.”

The captain told the first officer, “Okay, Jim you watch and make sure I go the right way.”

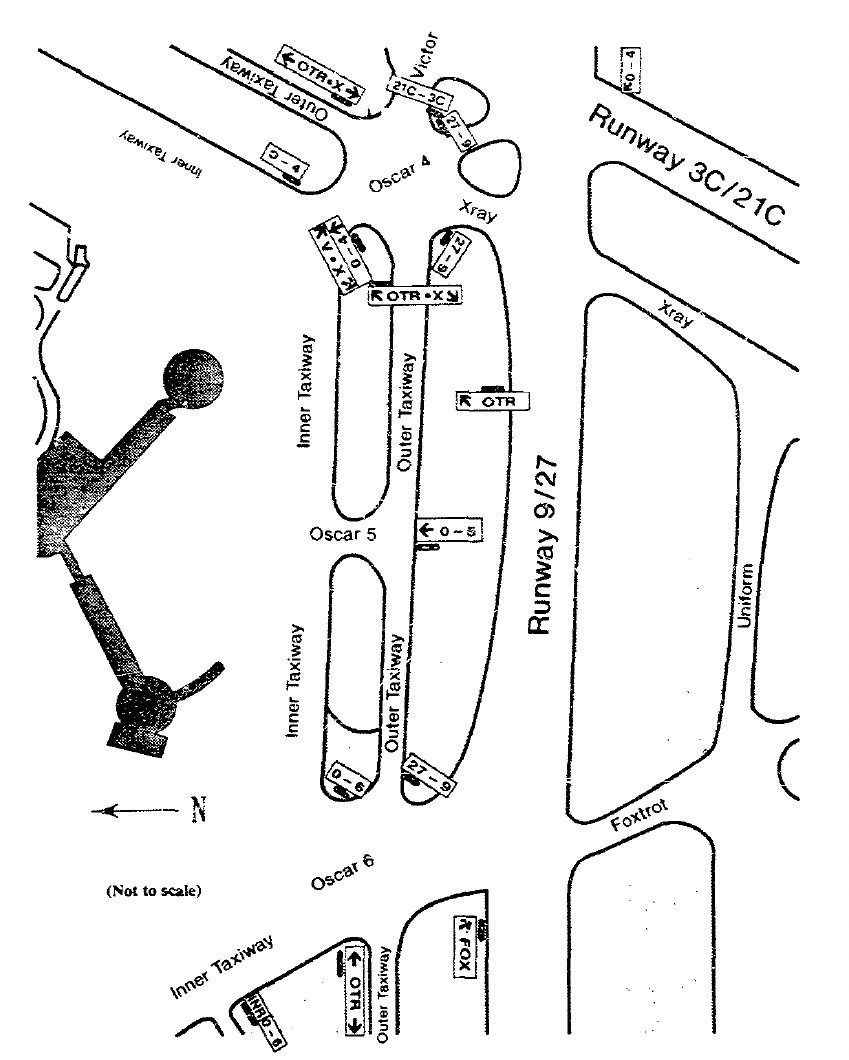

The airport, at the time, was laid out with inner and outer taxiways around the terminal with spokes radiating outward called Oscar. Their clearance was to Oscar 6 which crossed Runway 9/27 and then became Taxiway Foxtrot, which ended with a right turn to Taxiway Xray, which took them to runway 3C. There were several issues, however. First, the taxiway centerline of the inner taxiway was so faded, it would have been difficult to see in good weather. Second, the weather wasn’t good.

The captain stated that he was able to find and follow the yellow line. (But it became apparent that he did not find the correct yellow line.) They switched frequencies and the ground controller asked for their position. (The visibility was so bad they couldn’t be seen from the tower, which was not equipped with Airport Surface Detection Equipment, ASDE.) When the first officer reported they were passing the fire station, ground control cleared them to taxi via the inner taxiway, Oscar 6, Foxtrot, and to report making the right turn onto taxiway Xray. The crew never found the centerline of the inner taxiway and by the time they saw a sign for Oscar 6, they had passed it. The first officer said, “guess we turn left here.” The Captain said, “left turn or right turn?” The first officer said, “yeah, well this is the inner here, we’re still goin’ for Oscar.” The captain said, “so a left turn.”

The crew thought they were on Oscar 6, but they were actually on the outer taxiway.

When asked for their position by the ground controller, the first officer responded that they were eastbound on Oscar 6, which runs north-south. The ground controller asked them to report passing Runway 09/27. The first officer then said to the captain, “I think we might have missed Oscar 6, see a sign here that says ah the arrows to Oscar 5. Think we’re on Foxtrot now.” [AAR-91/05, p. 5] But Oscar 5 doesn’t intersect Foxtrot. The crew was clearly lost.

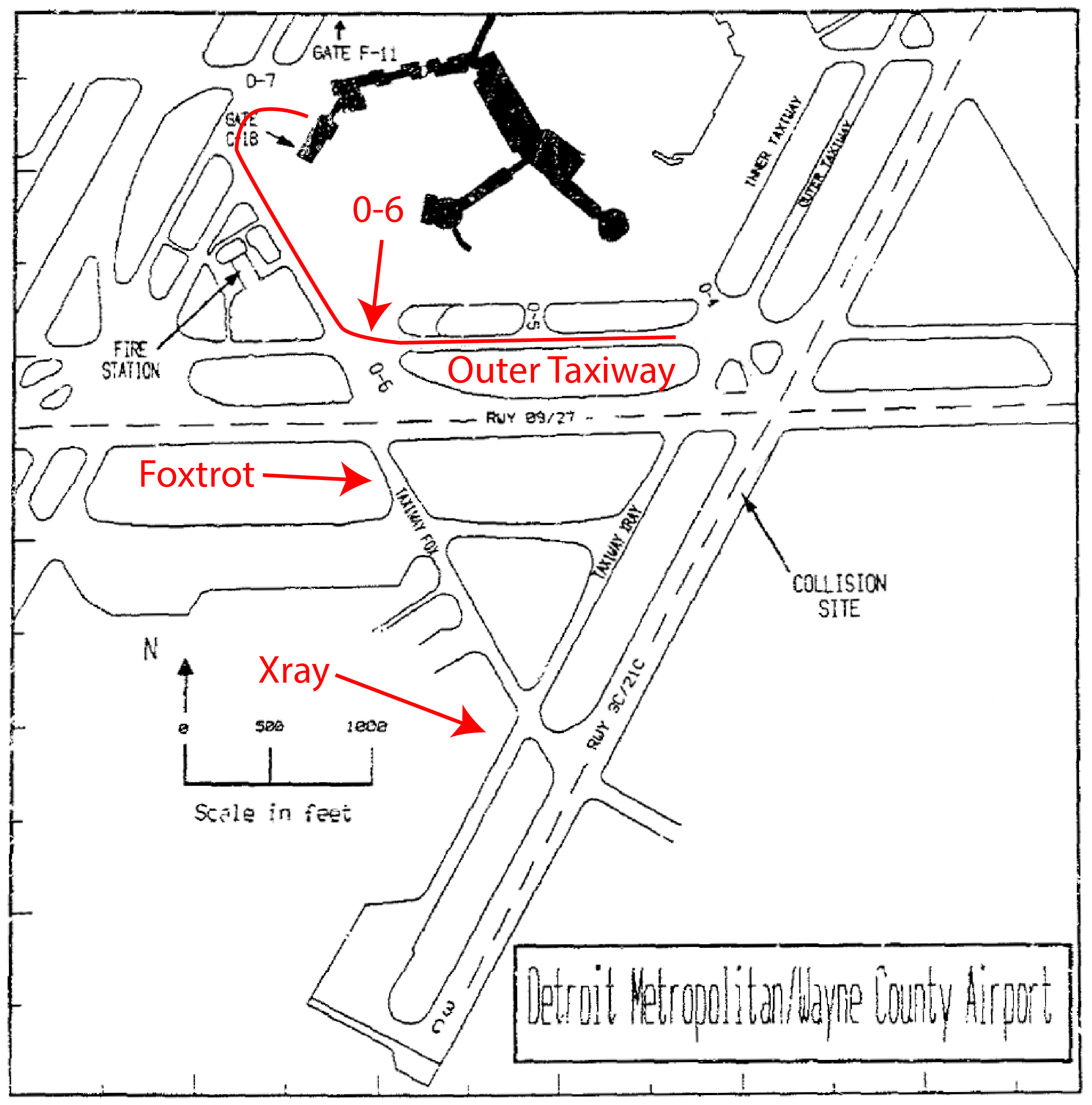

The ground controller figured it out, saying “Northwest 1482 you just approached Oscar 5 and you are on the outer.” The first officer acknowledged, “Yeah, that’s right.” The controller gave them a new clearance, “continue to Oscar Four then turn right on Xray.”

By the time they got that clearance, they had passed the sign for Xray:

↖OTR • X ↘

In the six-way intersection to come, they saw three runway signs:

21C – 3C and

27 – 9 and another

27 – 9

The way the signs were laid out, if you got to Oscar 4, you will have passed the turn for Xray. The only right turn remaining gets you onto runway 9/27 immediately followed by 3C/21C.

The captain asked, “So what’s he want us to do here?”

The first officer replied, “You can make the right turn, he said and report crossing two seven, and then I’ll ask him.” The first officer then said, “there’s Oscar 4, this is Xray.” But Xray was already behind them. They instead turned right on Oscar 4 and to the intersection of both 03C/21C and 09/27 runways.

3

The runway incursion and aircraft collision

During all of this, Northwest Airlines Flight 299, a Boeing 727, had been cleared to runway 3C, a few minutes behind 1482. The captain on that flight was concerned that the visibility reported on the ATIS was wrong. The visibility looked far worse than the reported ¼ statute miles, which was their minimum. As it turns out, the tower controller estimated the visibility without referencing known landmarks and a chart designed for the purpose. An off-duty controller preparing for her shift did use the known landmarks and chart and concluded the visibility was only 1/8 of a mile. She informed the on-duty controller who declined to issue a change.

As soon as Flight 299 reached the runway, they were cleared to takeoff. The captain moved them into position but delayed almost a minute to run the before takeoff checklist items and other tasks.

1344:15 TWR “Northwest two ninety nine, Metro tower, runway three center, wind one one zero at eight, clear for takeoff, turn right heading zero four zero.”

The Flight 299 first officer acknowledged. The captain, first officer, and second officer accomplished the required checklist.

1345:03 Cockpit Area Mike (sound of increasing engine noise)

1345:08 Cockpit Area Mike “Definitely not a quarter of a mile, but ah, at least they’re callin’ it.”

[AAR-91/05, pp. 96 – 97]

Some pundits say the crew took 48 seconds to run the checklist and discuss the weather before starting the takeoff roll. From the Cockpit Voice Recorder transcript, it appears that time was used on the checklist and the weather comment came after the throttles were advanced. But both points bear mentioning. First: the tower controller couldn’t see the airplane and assumed they started their takeoff when he cleared them. Second: the pilots knew they were taking off below minimums but were okay with that, since they had someone on tape telling them the weather was better than it was.

Meanwhile, the captain of Flight 1482 spotted a runway edge light and said, “this is the active runway here, isn’t it?” The first officer said, “yeah, this is nine two seven,” probably thinking they were on Xray. The captain asked, “we’re cleared to cross this thing, you sure?” The first officer said, “That’s what he said, yeah.”

But as the edge of the runway came into view, there was only grass, not the continuation of taxiway Xray. The captain stopped the aircraft in the middle of the intersection of both runways. The ground controller asked for their position. The first officer replied, “ah believe we are at the intersection of ah Xray and ah nine two seven, holding short.” Of course this was not at all true. The controller cleared them to cross and continue on taxiway Xray. The captain started creeping forward, but then realized they were on two runways. He directed the first officer, “tell him we’re out here. We’re stuck.” The first officer did not do this. The captain taxied to the left edge of Runway 03C, with his right wing protruding out to the runway center.

The ground controller called, “verify you are proceeding southbound on Xray now and you are across nine two seven.”

The captain answered, “we’re not sure, it’s so foggy out here. We’re completely stuck here.”

The controller asked, “are you on a taxiway or a runway?”

The captain said, “We’re on a runway by Oscar 4.”

The ground controller asked again. The first officer said, “we’re on two one center.” The captain said, “Yeah, it looks like we’re on two one center here.” The ground controller asked again a few times until he told the rest of the tower he had a lost aircraft on an active runway.

The tower supervisor said to each controller, “Stop all traffic!”

The ground controller transmitted, “Northwest 1482, if you are on two one center exit that runway immediately.”

The tower controller considered telling Flight 299 to abort, but since he had been cleared to takeoff almost a minute ago, he assumed they were off the ground already.

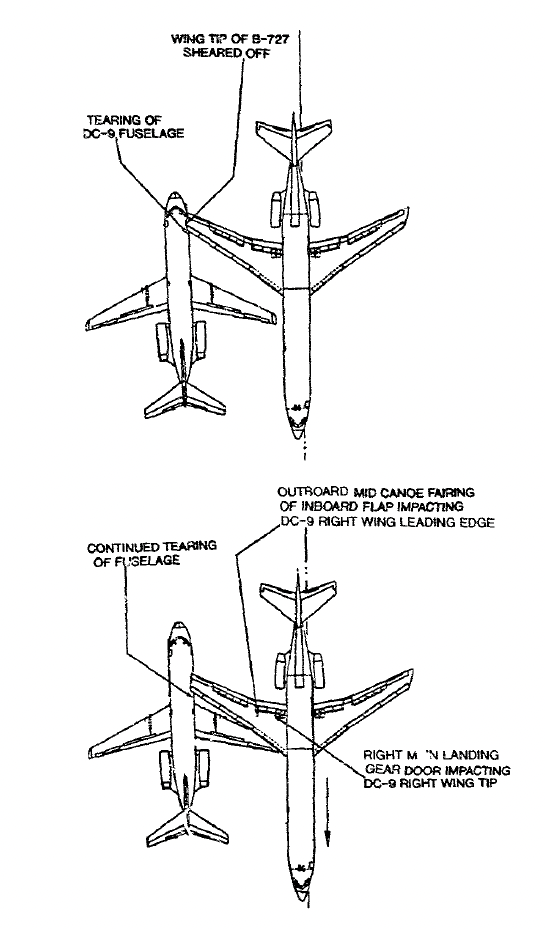

The captain on Flight 299 spotted the DC-9 at the last moment and attempted to veer left, but it was too late. The 727’s right wing contacted the right side of the DC-9 and sliced through the fuselage, along the line of windows. Three passengers seated on the right were killed instantly. The DC-9s right engine was ripped off its pylon and the airplane was quickly engulfed in flames. The captain on the 727 was able to abort the takeoff and no one onboard was injured.

By the time the fire trucks reached the DC-9, it was completely engulfed in flames. All the exits on the right were either destroyed or blocked by fire. The tail cone exit was inoperable because of a mis-rigged handle; a passenger and flight attendant died in the tailcone trying to open it. The passengers got to the forward left exit before any flight attendants and failed to open the door completely, so the slide didn’t activate and they ended up jumping to the ground. A passenger managed to get the left overwing exit open and most of the passengers exited there. A total of 8 passengers and 1 crew were killed, with 10 more passengers seriously injured.

4

Lessons learned

Many of the recommendations of this 1991 accident report have since been enacted and taxi operations are safer as a result. But, as is true with many human factors realizations, the lessons need to be taught to every generation or they will be forgotten. Here is the NTSB’s bottom line about this accident:

Probable Cause

The National Transportation Safety Board determines that the probable cause of this accident was a lack of proper crew coordination, including a virtual reversal of roles by the DC-9 pilots, which led to their failure to stop taxiing their airplane and alert the ground controller of their positional uncertainty in a timely manner before and after intruding onto the active runway.

Contributing to the cause of the accident were (1) deficiencies in the air traffic control services provided by the Detroit tower, including failure of the ground controller to take timely action to alert the local controller to the possible runway incursion, inadequate visibility observations, failure to use progressive taxi instructions in low-visibility conditions, aid issuance of inappropriate and confusing taxi instructions compounded by inadequate backup supervision for the level of experience of the staff on duty; (2) deficiencies in the surface markings, signage, and lighting at the airport and the failure of Federal Aviation Administration surveillance to detect or correct any of these deficiencies; and (3) failure of Northwest Airlines, Inc., to provide adequate cockpit resource management training to their line aircrews.

Contributing to the fatalities in the accident was the inoperability of the DC-9 internal tailcone release mechanism. Contributing to the number and severity of injuries was the failure of the crew of the DC-9 to properly execute the passenger evacuation.

[NTSB AAR-91/05, p. 79]

Enduring lessons

The people who designed the airport taxiway markings and signage got it wrong and the FAA allowed the airport to operate this way. The airline failed to institute Crew Resource Management training long after their competitors. The air traffic controllers issued confusing instructions, failed to intervene when they should have, failed to correct faulty visibility reports, and failed to stop active runway operations when it became obvious they had a lost airplane on an active runway. The pilots of Flight 299 took their time after being cleared for takeoff and elected to takeoff even though they realized the weather was below their minimums. The first officer on Flight 1482 told a series of lies to lure the captain into ceding his authority. The captain allowed that to happen. What do we make of all this?

First: the mechanical lessons about operating airplanes on the ground in dynamic environments. Never move the aircraft unless you know where you are and where you are going, and before briefing the route. If you are lost, stop the airplane someplace other than a runway, set the parking brake, and let everyone know. When in doubt, ask for progressive taxi.

Second, perhaps more importantly: the authority gradient. A first officer on probation wants to impress the captain but an attempt to build oneself up can cause the captain to overestimate the first officer’s abilities. When the first officer becomes too assertive in the cockpit, the captain may be tempted to cede his or her authority. The inverted authority gradient may be worse than the steep authority gradient. In the case of the latter, you turn a two-pilot crew into a single pilot crew, but at least that pilot is captain qualified. In the case of the former, you end up with no captain at all.

Third, most importantly: taking our jobs seriously. Many of the decisions made by individuals could have been rationalized at the time as unimportant. Why bother checking the tailcone handle from the inside? It never gets used! Why worry about some faded taxiway paint? The pilots know where they are going! Why update the runway visibility? A 1/8 of a mile less difference is hardly worth mentioning! Why study the taxi diagram? The first officer knows this stuff! On and on. Had any one of these small decisions, and several others, been treated more seriously, the people who died aboard Flight 1482 would have made it to Pittsburgh instead of the morgue.

References

(Source material)

Aircraft Accident Report AAR-91/05, Northwest Airlines, Inc., Flights 1482 and 299, Runway Incursion and Collision, Detroit Metropolitan/Wayne County Airport, Romulus, Michigan, December 2, 1990, National Transportation Safety Board, June 25, 1991

“Taxiway Turmoil,” Mayday, Season 20, Episode 4, aired 16 January 2020

“’Exit That Runway IMMEDIATELY’ 7 Seconds From Impact?!” Mentour Pilot, July 19, 2025