As aviators, we instinctively realize we sometimes need to focus intensely during flight and that if we allow ourselves to be distracted, things can go very wrong, very quickly.

— James Albright

Updated:

2022-02-15

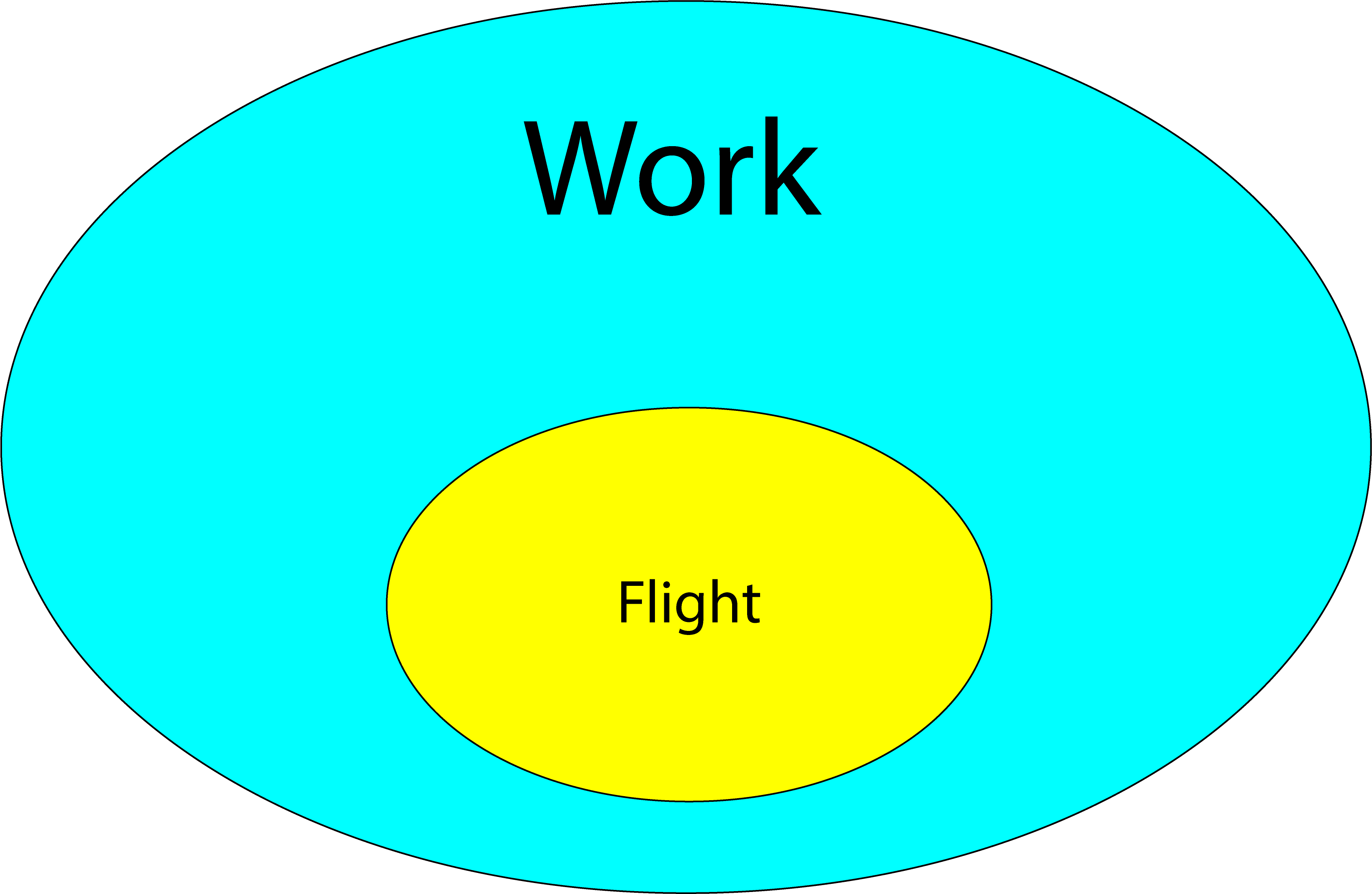

In earlier chapters, we covered techniques on how to improve our focus by compartmentalizing our lives as aviators to the exclusion of all distractions. By building an aviation “compartment,” we are better prepared to switch on the focus when needed. In subsequent chapters, we learned that we also have social pressures that make this compartmentalization harder to do and that our family life deserves a compartment of its own. But what about your work environment? If your work is aviation, how do you compartmentalize one from the other?

1 — Defining the “flight compartment” versus the “work compartment”

2 — Problems that can crowd into flight compartment

3 — Understand the environment

4 — Understand yourself (Patient: heal thy self)

1

Defining the “flight compartment” versus the “work compartment

How do you differentiate between the flight compartment and the work compartment when flying is your job? It may be tempting for you (and your employer) to say your work encompasses your flying, so everything is work.

We know intuitively that can’t work because we know our flight compartment needs to be free from distraction. But the two compartments are not actually distinct.

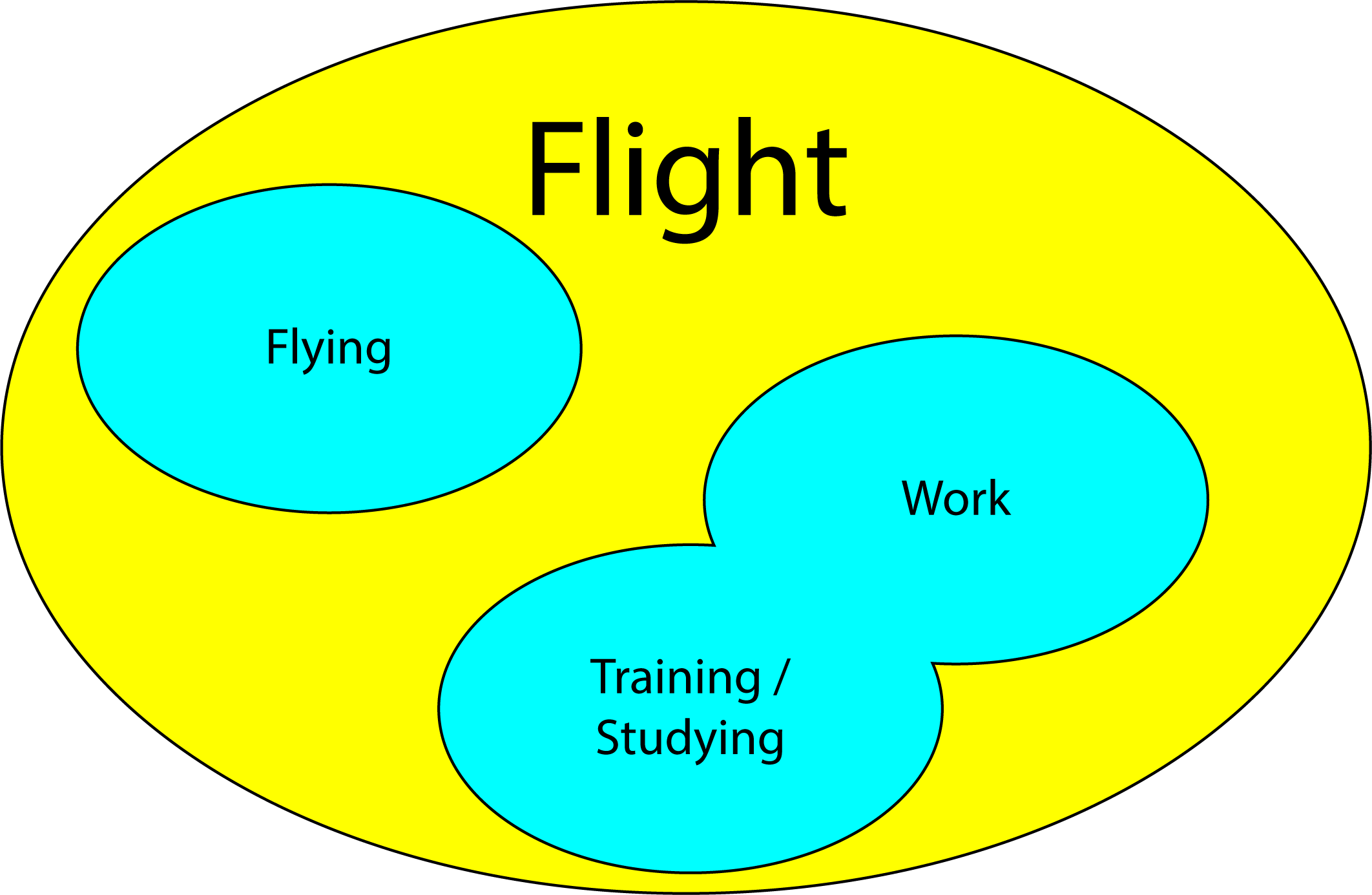

I prefer to say the flight compartment encompasses many other compartments, including work. Work has a direct impact on many parts of your flight compartment, but the actual flying remains distinct and separate.

Keep in mind that inside the “Flying” compartment are many smaller compartments, such as “Takeoff” or “Cruise with autopilot engaged.” Some compartments are absolutely separated from distractions while others are not. The key distinction is that while your employer controls many aspects of your life as an aviator, you must keep the actual flying above those influences. The distinction isn’t perfect, I admit. The employer will determine your SOPs, for example. But once you’ve accepted those SOPs as your own, when you are out there flying airplanes, you need to follow those SOPs as your own. You cannot allow outside influences to collide with your actual flying.

2

Problems that can crowd into flight compartment

While I flew for quite a few bosses in the Air Force that I would place into the “unreasonable” category, their unreasonableness rarely crowded into the flight compartment because our SOPs were so well defined. In the civilian world, my first few jobs made for good case studies on just how badly work place issues can distract one from the business of flying airplanes. There are other problems that can create a problem of focus, but here are a few as examples.

Laissez faire boss. Larry was my first civilian chief pilot. He was a competent pilot with a long history of managing flight departments and whose chief distinction was that he had no distinction whatsoever. His goal was to slowly creep to retirement without upsetting anyone and his number one rule as a leader was to have no rules. The troops, as a result, flew by their own rules. For example, if they wanted to get to Italy in a single day even though it violated company flight duty limitations, so be it. We had a sterile cockpit rule in our manuals, but not in our cockpits. When the person on top has no standards, the standards sink to the lowest among the people below.

Unreasonable boss. George took Larry’s place and set out to do everything as he remembered from his time as an Army platoon commander. He made it clear that we would fly by his rules and his rules only. Our company had a rule against flying without an instrument clearance, for example. He would allow us to file IFR but if it was more convenient to go VFR, that’s what he would do. He was “in command” for less than a year, but in that time, we slowly gravitated to a rogue flying operation, with no rules at all. Once again, we lost the “S” in our SOPs.

Lackadaisical coworkers. With both Larry and George, we in the trenches resorted to adapting our flight procedures for each trip, based on crew composition. A few of us ex-Air Force pilots, resorted to “by the book” procedures when we could. More of the pilots, however, wanted to fly with as few rules as possible. The more senior pilots tended to get their ways, which meant the junior pilots had to guess at what to do.

Non-standard Standard Operating Procedures. After George was fired, we got a good boss who set about fixing everything that was broken. Unfortunately, our company was bought out and our flight department was terminated before he could finish the job. I moved to a newly formed flight department led by a boss who had never been exposed to any operation with more than a few pilots or tightly enforced SOPs. The result was utter chaos. “We need to plot the route,” I said on my first oceanic flight with him. “Why do you always have to make simple things difficult?”

Inadequate training. Many years ago, I joined a flight department where the pilots didn’t do complete exterior preflight inspections, the mechanics used unauthorized methods to maintain the aircraft, and the only training we ever had was at the simulator. The simulator vendor’s prime directive was to collect our money and make the training and evaluations as easy as possible so that we would come back and give them more money. Our flight department was managed by a company I started to call “Head in the Sand Aviation LLC” that did no management at all. Our chief pilot ran the flight department as he would have a personal flying club. Nobody minded me doing the preflight inspections, but they didn’t want to make the callouts in the manuals and the mechanic was unhappy whenever challenged. I thought the situation bordered on unacceptable, but more on that later.

Each of these example situations can make it more difficult or impossible to keep your focus on flying when that focus needs to be razor sharp. For these and other situations, your solution will depend on your motivations, your standards, and for just how much you are willing to tolerate.

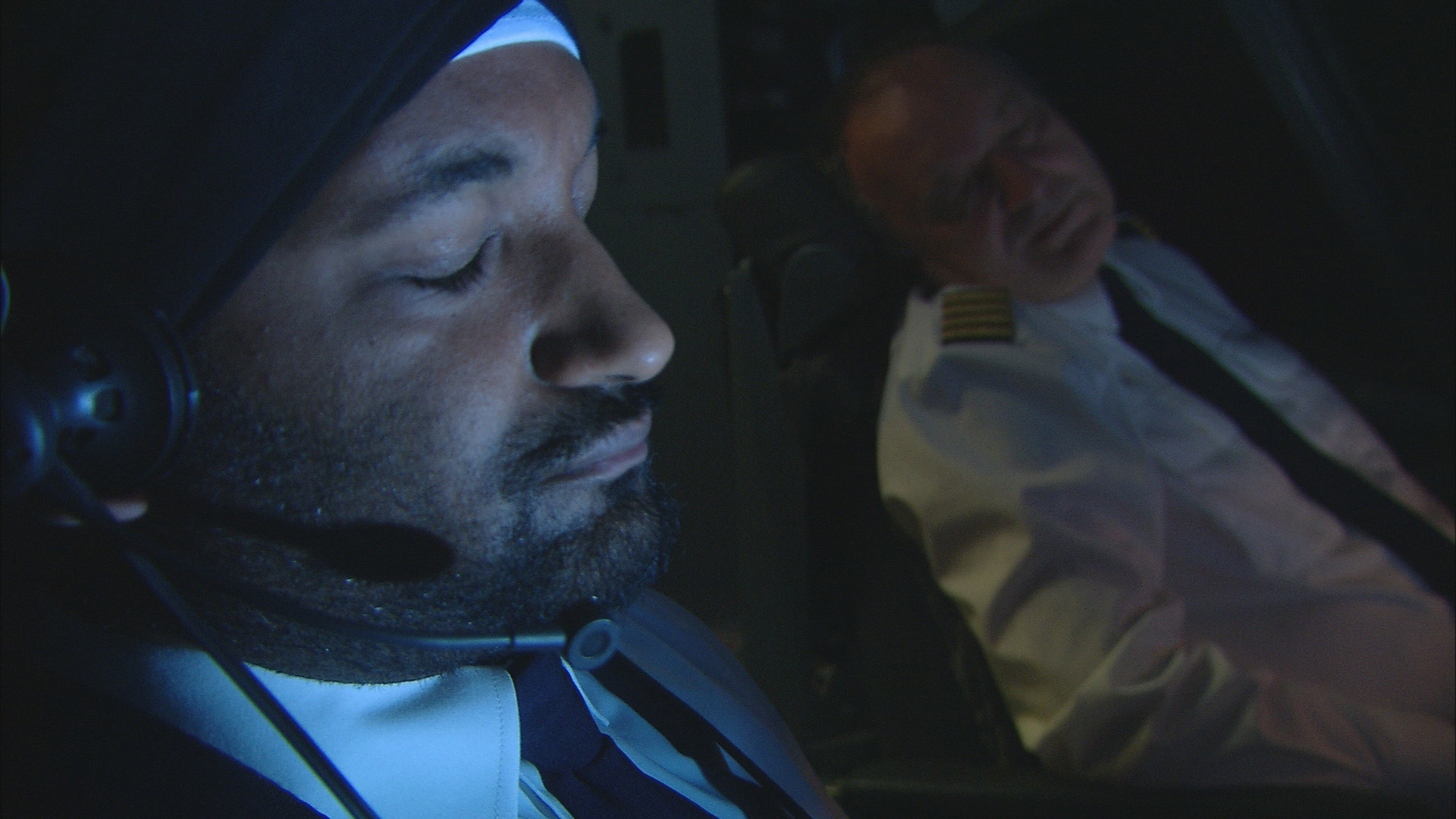

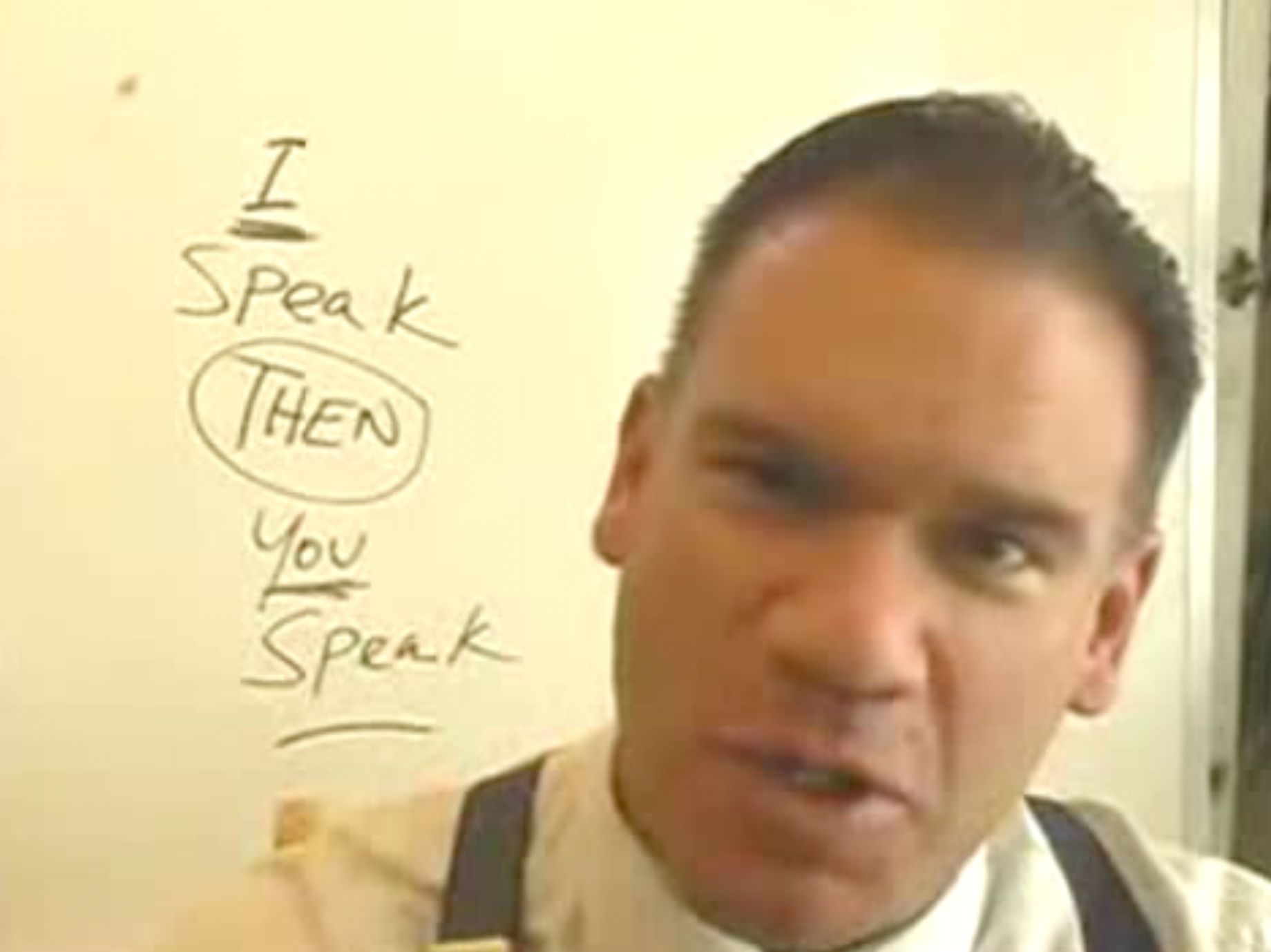

Nightmare boss, (Paul Parducci)

Click photo for video

3

Understand the environment

Regardless of where you are now in the long spectrum of aviation jobs you will have during your career, you are no doubt ahead of where you were a few years ago and probably on your way to something even better. On your way “up the pyramid” of pilot jobs, something must be motivating you to put up with the long hours, the time away from home, or any of the things that make where you are now, not as good as where you want to be. “Building time,” is a common motivation. We used to say in some parts of the Air Force, “you can’t go unless you’ve been.” An impossible statement but the point is clear: you need a certain level of experience to be hired for a certain level of responsibility. So, as a result, you put up with less-than-ideal conditions to build your experience.

What if those less-than-ideal conditions force a compromise with your personal standards or limitations? We are all in the “I am here to learn and be the best pilot on staff” when starting a new job as a pilot. We aim to please and that necessarily requires we forget how we’ve always done something to adapt to the new environment. In many of my Air Force jobs, having a 20-hour duty day and being away from home between 150 and 200 days each year was the norm. My first civilian job had a manual that specified much shorter days (14 hours for a basic crew of two pilots and one flight attendant) and fewer days on the road (typically 120 days per year). My first international trip with the new job was scheduled to have a 14-hour day heading to Europe and a 16-hour day coming home. When I asked, I was told “that’s the way we’ve always done it.” I said nothing in complaint. It wasn’t as bad as some of my Air Force jobs and I wanted to be a team player.

The trip home included a delay starting the day and another delay at an en route stop. I found myself nodding off somewhere over the U.S. and startled myself when my head bobbed backwards. I looked to the other seat and found the other pilot sound asleep. We landed 20 hours after we first assembled as a crew that morning in Italy. Our company rule book limited us to 14 hours. I went home exhausted.

It was my first civilian job and I wanted to do well. I was pilot number nine of nine pilots, the last hired who could be the first fired. None of the other eight pilots objected to the trip, which happened once a month. In a few months, I would have to do it again. In my Air Force squadrons, we had provisions in writing which required the very long days under very controlled circumstances. Here in my new job, we were operating outside our own rules. I decided I wasn’t going to do that. I confronted the chief pilot who said he couldn’t exempt me from the trip when everyone else had to do it. The word got out and suddenly I had more than half the flight department on my side. We started prepositioning crews for the trip and everyone was happy, except the chief pilot. I am sure I lost favor in his eyes, even as I gained respect with my peers. Was it the right thing to do? It is a decision you will have to make for yourself.

4

Understand yourself (Patient: heal thy self)

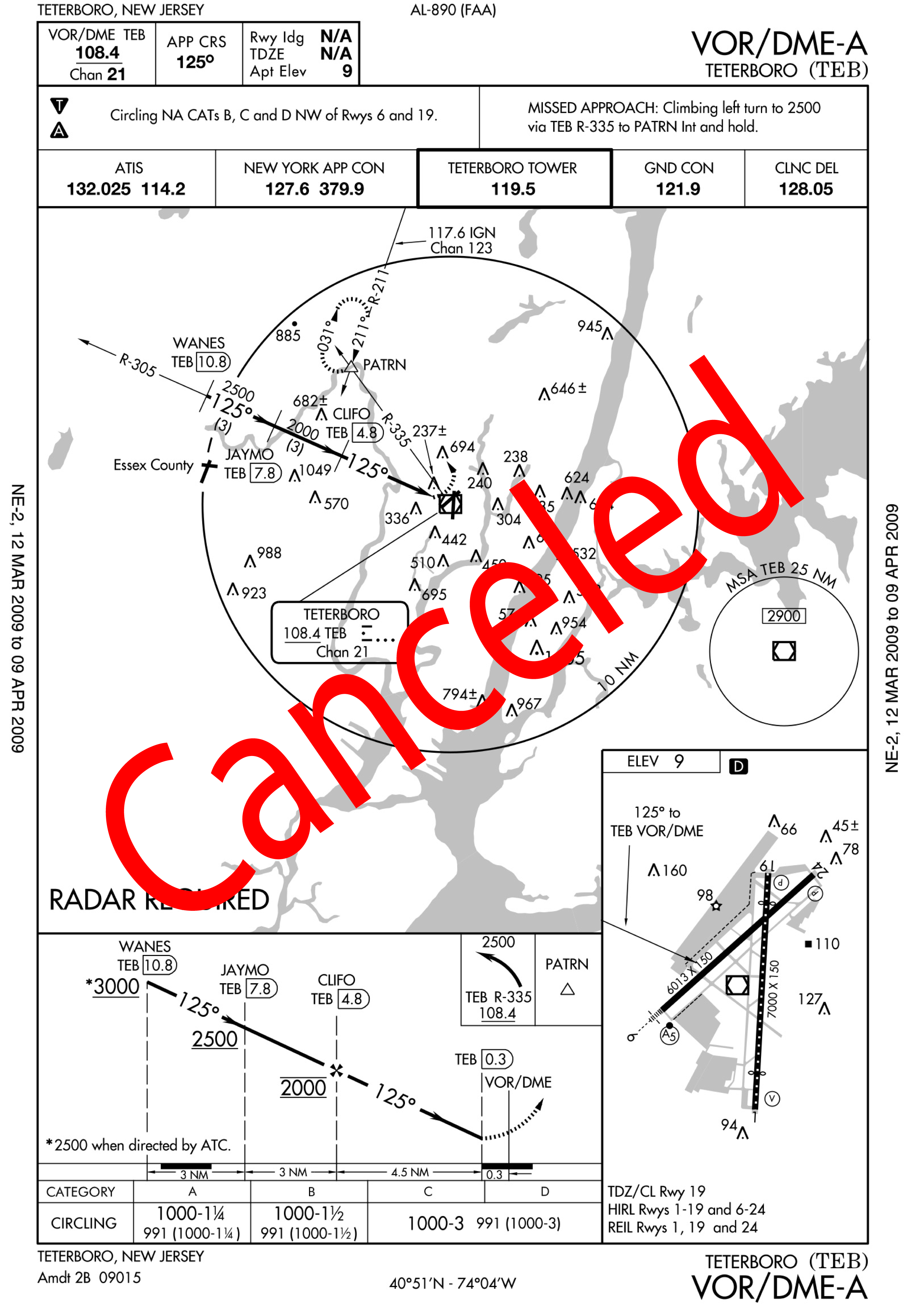

When analyzing a situation that appears beyond all reason, you must first ask yourself if the problem isn’t that you don’t have the knowledge or required skills. But that might be a fruitless attempt because you may not know what you don’t know. I found myself in that situation during my first approach at Teterboro.

The pilot I was paired with acted as if it was the most normal thing in the world. The weather was clear, the winds were gusty, and there were airplanes all over the place. Our instructions were to fly the VOR/DME-A from WANES, fly over the runways at 1,500’ and 190 knots, and then turn downwind for Runway 19 while avoiding the LaGuardia airport traffic area and a hospital on final and remain inside one highway which seemed indistinct from the other ten or twenty in the area. Simple!

I felt unsure about when to turn downwind and once I did that, I wasn’t sure I had the runway in sight behind us and to our left. Meanwhile I wasn’t sure I had the two aircraft in front of us in sight or a helicopter tracking for a hospital situated on runway centerline. It was madness.

My first instinct was to say my flight department was nuts for flying to Teterboro at all. The airport seemed like an uncontrolled mess; Newark or LaGuardia would be better options. (I’ve since heard some flight departments have made this very decision.) This was in the year 2000, a year after Teterboro activated an ILS to Runway 19. None of our pilots would dial the ILS because they already had the VOR tuned for the initial flight over the runway. I adopted the habit of tuning the ILS once we were headed over the runway and that made things much easier. In the years to come, I’ve found that Teterboro is certainly safe but requires pilots with very good situational awareness and in some cases, very good stick and rudder skills. I have diverted a few times because I thought the conditions were too risky. But when scheduled for a TEB trip, I usually go without any reservations.

Note: the approach has since been canceled. I think they realized it was a handful for pilots without a lot of Teterboro experience and that using the ILS made things less hectic for all involved.

You may find yourself thinking you are in a flight department that has gone nuts. But you should pause and analyze the situation further. It could be that they know something you don’t, or that they have an ability that you don’t. Gaining the missing knowledge, skills, or experience might be the answer. (And it will make you a better pilot.) Compare notes with your fellow pilots and ask around. But even if it all checks out, you might decide that it is a situation you cannot tolerate. What then?

5

Having a good plan B (or C, or D, or . . .)

As a professional pilot, your flight compartment may take precedence over your work compartment, but cannot exist without it. You might have to put up with a less than ideal work situation while you build time and experience, or if the economy is such that finding another job isn’t an option. But what if your work situation fosters unsafe practices that jeopardize safety and/or your license? For those situations you need a “Plan B,” or C, or D, and so forth. These could be other jobs in the area, a job as a contract pilot, jobs in other areas, or even non-flying jobs.

I’ve had two civilian jobs disappear when the flight department was dissolved, or the company went bankrupt. In the first case I moved halfway across the country to where the work was, and in the second case I found a job with a bit of a pay cut. Along the way I quit another job when the company refused to adopt what I thought were necessary safety measures. I had a “Plan B” job that involved another pay cut, but I figured that was better than risking life and limb with a company that didn’t see things the way I did. This kind of decision is obviously traumatic and therefore a personal one. It always pays to cultivate options, even if your current situation seems secure. A few to consider:

- Life as a contract pilot, working on a per diem basis.

- Moving out of the area, to where the work is.

- Working as an instructor for a training vendor.

- Taking a break from aviation and working in the local area until a flying job to your liking comes open.

Of course, there are many other Plan B options out there. The key is to have the Plan B ready to go, before you need it. Having the option ready to go makes your decision making easier if you find yourself with a work situation you cannot deal with.

6

Short of plan B: dealing with it

Unless you find yourself in a safety of flight situation, you might be better off learning to deal with the problems and coming up with solutions when you can. I’ve been through the process several times; my plan is usually to get the organization to see things my way, usually subtly but sometimes not. I ended up using a wide range of techniques while at “Head in the Sand Aviation.”

Mitigation strategy: recruit

I was hired as the third pilot at “Head in the Sand Aviation,” where the chief pilot had more Gulfstream GIV time than me, but the second pilot was new to Gulfstreams and only SIC qualified. I was immediately qualified as a PIC and decided unilaterally that we would do a complete exterior preflight whenever I was flying. The boss didn’t mind, so long as he didn’t have to do the preflight himself. Our mechanic seemed to take personal offense during my first preflight but got over that once I explained I wanted to learn more about the airplane. One day, our SIC-only pilot discovered a hydraulic leak that had developed since the mechanic’s post flight of the previous day, giving us time to get the airplane repaired prior to flight. Our mechanic became a sudden proponent of pilot preflights, so the chief pilot finally gave in.

Lesson learned: if you find a situation unacceptable, chances are you aren’t alone or others don’t understand the consequences of the problem. Getting them to see they are also at risk or that the change you have in mind will help them, can win allies in your efforts.

Mitigation strategy: convince

Our chief pilot considered the after-start checklist a race to see who could flow it the fastest, saying he had been doing it that way for ten years and wasn’t about to agree to my need to have the right seat pilot read the checklist while the left seat accomplished it, step-by-step. He said flowing the process to completion prior to a recitation of the checklist was faster and gave us two opportunities to catch errors. But I wondered about the error rate. After just a month of this, I noticed we quite often made it to the runway without the aircraft correctly configured. I started timing his method and logged the times along with the number of errors. Then he agreed to try my method for a month, and we again recorded the times and error rate. The results were surprising. The “flow, check” method was not only more prone to error, it was actually slower. He agreed to adopt my method.

Lesson learned: Sometimes the best way to convince someone they should consider another idea is to try their idea first and then put yours up against theirs. You might find you were wrong all along, or the other person may find out you were right. In either case you end up in a better situation.

Mitigation strategy: outlast and conquer

Our passengers often showed up hours late, but they understood that turning a long day into a very long day could be hazardous to everyone’s health. So, they made it a point to ask us prior to every delayed flight if we were okay to fly. The chief pilot agreed it would be better to have iron clad duty limits, but at least having the option to say no was better than no option at all. So, I lived with it. All that changed when a planned 3-leg, 14-hour day turned into 18 hours from start to finish. The first legs took off three hours late, and the second leg added another hour. The third set of passengers asked me if I was okay to fly. I said I was fine. Of course I was fine! I was only 10 hours into the duty day. Seven hours later, on approach in a driving rain storm, I wasn’t fine after all.

I spoke with the other pilots, and we agreed to impose our own limits, patterned off industry accepted norms. The chief pilot said it would be up to me to break it to our passengers if I decided one day that I wasn’t “fine” with extending the duty day. As it turned out, I got my chance almost immediately when the CEO asked me if I would be willing to take over. I said yes, provided we could adopt a flight operations manual that included flight and duty rest limitations. And that is what happened. The first few times saying we couldn’t meet a long day’s timing seemed to take some of our passengers by surprise. But they now ask us if schedules are feasible before publishing itineraries.

Lesson learned: In a situation that is obviously wrong, the resistance to change can be due to the fact “we’ve always done it this way and saying we can’t do it any longer begs the question, why did you ever do it in the first place?” A change in leadership is an excellent time to do this but there is also nothing wrong with saying, “we re-evaluated the situation and decided it would be prudent to make a change.”

Mitigation strategy: compartmentalize work

Soon after I took over I fired the management company and took our operation “in house.” Along the way I’ve had some push back from the company and from some of our pilots and mechanics. We’ve evolved from a flight department without standard operating procedures and a lot gray operating areas, to one that is about as “by the book” as any I’ve ever been a part of. I’ve learned a few lessons over the years with what I used to call “Head in the Sand Aviation” that can help outline a way to compartmentalize work from flight.

- Set boundaries

- Establish your flight compartment as your personal “safe space”

- Frame the need to separate work from flight as a “you” issue, not a “they” issue

- Lead by example during flight and the debrief

The strictest interpretation of “sterile cockpit rules” that I’ve heard prohibits any verbal communication except callouts specified in manuals whenever the aircraft is below 10,000 feet AGL or within 1,000 feet of leveling during a climb or descent. I’m not sure this is particularly useful, and I doubt it is a rule that is faithfully followed. But the idea of establishing easily defined boundaries with rules makes sense. More lenient sterile cockpit rules allow any flight related chatter. But what is really flight related?

In 2009, the pilots of a Northwest Airlines Airbus A320 overflew their destination by 150 miles because the pilots were, they said, in an animated discussion about company work rules. The discussion was during cruise flight and was, in a sense, flight related. But clearly their 78-minute absence from the radio placed the lives of the 158 people on board at some risk.

I suggest you establish at least three compartments where nothing other than required callouts or other conversation strictly needed for the activity at hand can be discussed; (1) During takeoff until the aircraft passes 10,000 feet or reaches cruise altitude, which ever occurs first. (2) During approach and landing. (3) For climbs and descents below 10,000 feet and when within 1,000 feet of leveling off regardless of altitude.

I also suggest that at other times any idle conversation should be light and should not include the normal taboos in polite society (religion, politics, sex) or anything controversial related to work. The cardinal rule here is you don’t want something that has the chance of putting you at odds with the rest of the crew or could monopolize your attention.

As much as I dislike the term, I tend to think of the cockpit as my personal “safe space.” I have known procedures to follow and when I follow them, I have known outcomes. I try very hard to prevent workplace issues from invading. This becomes particularly difficult when your passengers bring the work forward into your safe space. If that happens during one of the set boundaries mentioned before, I ask the invader to “hold that thought” until in cruise flight or on the ground. And once we are there, I make a bit of a scene briefing the other pilot to take control of the aircraft and radios, and to give that pilot permission to call “knock it off” if he or she needs my assistance. That should telegraph the person bringing the work to me that I have business of my own to attend to, and that my business could be more important than theirs.

If your coworkers don’t have a problem with having long, drawn-out discussions or debates about work (or anything else) during flight, you should ask to table the talk until on the ground. If asked if you have a problem with them doing that, say it isn’t them that you are worried about, but that you would like to give your full attention to the matter and cannot do that while also giving your full attention to the flight.

You will not be perfect in these efforts, but you cannot allow this to discourage you from continuing efforts. Part of your flight debrief should include falling short of sterile cockpit procedures or these kinds of distractions during other periods of flight.