When I first heard the term “authority gradient” applied to cockpit human relations, I thought it was another attempt by the human factors gurus to complicate something that should be simple. The captain is the captain, and everyone else had better know that. Of course, that is a recipe for a Crew Resource Management (CRM) disaster. The captain is the captain; but the captain who doesn’t fully embrace the crew concept might as well be solo. Human behaviorists look upon captains with overbearing, dominant and dictatorial styles of leadership – those who exercise steep authority gradients – as particularly dangerous. I certainly agree, but I think there is another authority gradient that is even worse: the owner-pilot authority gradient. I am sure there are owner-pilots who are model CRM citizens. But owning the airplane can tempt some into megalomaniac behavior.

— James Albright

Updated:

2023-09-01

Much is made of the challenges of being an owner-pilot, and there are many. But a far worse position is that of the pilot assigned to fly with the owner-pilot. An Instructor Pilot (IP) is often required by insurance companies to allow the owner-pilot to fly an aircraft he or she would not be normally permitted to operate. While the IP is often technically the Pilot in Command (PIC), the IP is rarely in command of anything in these situations. The owner-pilot may have voluntarily agreed to such an arrangement in a good faith effort to keep things safe. But in either case, the arrangement can become one-sided, with the instructor too afraid to speak up for fear of losing the job. I’ve noticed the pressure can be even worse in a military environment where the instructor is saddled with someone far higher in the chain of command that while they don’t actually own the aircraft, they are the defacto owners. These owners, defacto or otherwise, tend to be poorly qualified, nonproficient, and often are unwilling to listen. This can be an accident waiting to happen.

1 — Example: The Hollywood A-List

3 — Example: The Air Force war hero

1

Example: The Hollywood A-List

In 1993 I was going through Gulfstream III recurrent training and shared classroom time with a highly experienced Gulfstream II/III instructor who tried to explain the differences between the older DC and new AC electrical systems of the II and the III. As it turned out, he was a battle-scarred IP with a unique perspective. He was flying in a GII along the east coast of the United States, with the owner-pilot in back entertaining his family and guests. When one of the DC generators fell offline, the IP methodically went through the checklist, knowing that he would either reset the generator or have to isolate a fault. In either case, the aircraft could press on with one less generator.

This well-paced and checklist-based approach was all for naught, however, when the owner-pilot rushed forward and hit a switch that spread the electrical fault to the rest of the airplane and they ended up with a complete electrical failure. If you read the National Transportation Safety Report, the aircraft then descended blind into the weather, popped out of the overcast at 1,000 feet, found an airport and landed. If you read press accounts at the time, the owner-pilot bravely rescued his aircraft and passengers from certain death. The IP told me that they made a rushed landing on an active runway against traffic, requiring an airliner to abort its takeoff.

Since all of this is second hand, I won’t reveal the names involved. I lead with this example to illustrate the bullet proof nature of some owner-pilots. The IP was obviously lucky to have lived through all this, though I am not sure his career survived.

2

Example: Royalty

The British Royal Air Force organization dedicated to flying the Royal Family from 1952 until 1995 was known as “Queens Flight.” In 1994 a Queens Flight British Aerospace BAe 146 was substantially damaged when landing at Islay-Gelengedale Airport (EGPI). The IP/PIC was RAF Squadron Leader Graham Laurie but “Prince Charles had taken over the aircraft’s controls as he often does on such occasions.” They landed with a 12-knot tailwind, crossed the threshold 32 knots hot, touched down nosewheel first, and the mains on the runway with only 1,700 feet of the 4084-foot runway remaining. Squadron Leader Laurie took full responsibility for the landing and was severely criticized in a Ministry of Defence report.

My first reaction was “Of course he took full responsibility, what else could he do?” But I imagine he was often in the position to make the “he can probably salvage this landing” position and the pressure to avoid a “royal go around” must have been extreme.

3

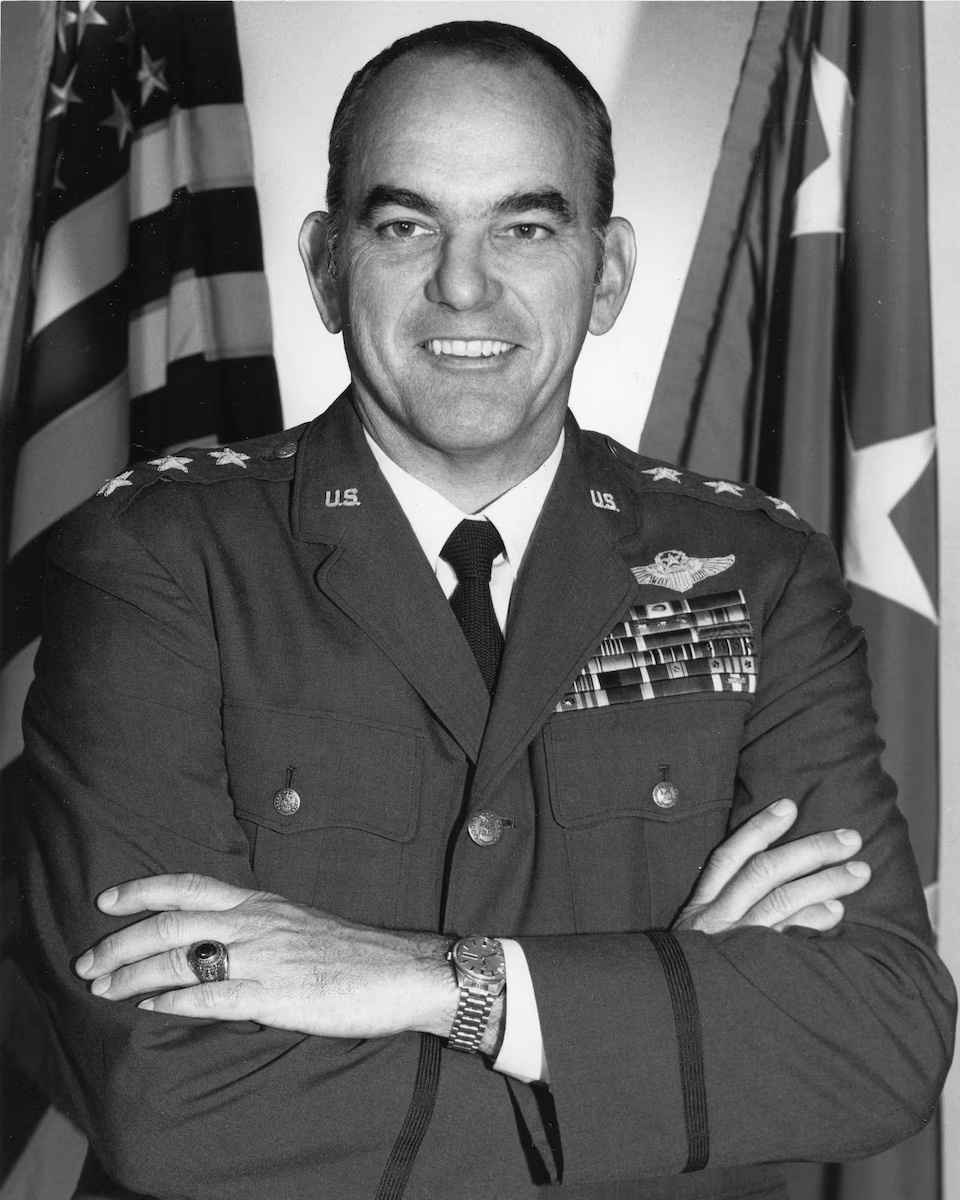

Example: The Air Force war hero

The last Northrop T-38 Talon delivered to the United States Air Force was a 1970 bird and was the aircraft of choice for the commander of the Air Training Command in 1972, Lieutenant General George Simler. General Simler was a bona fide war hero in the Air Force, having been shot down behind enemy lines during World War II and successfully evading capture. On September 9, 1972, General Simler was at the controls of a T-38 with his aide, an instructor pilot, in the back seat. Simler was to be promoted with his fourth star and was on his way to Scott Air Force Base to take over the Military Airlift Command. This was to be his last flight in the T-38. The aircraft was seen to rotate to an abnormally high attitude on takeoff, stall, and crash, killing both pilots. I requested the official accident report through the Freedom of Information Act. What I received was heavily redacted, claiming privacy concerns, but the names of both pilots were given.

The most probable cause given in the report was “the IP allowed the aircraft to be flown into a nose high, low airspeed, stalled condition at an altitude from which a safe recovery could not be made.” Conclusion: it was the IP’s fault.

A few years later I attended the Air Force Flight Safety Officer Course where our human factors classes were taught by Professor Chaytor Mason, on loan from the University of Southern California. Mason was called in as a human factors expert for the 1972 investigation and told our class that Simler was known to have bullied his aide to “never touch the stick” and had a propensity to over-rotate the aircraft. Mason’s conclusions were that Simler bullied his aide to the point the IP dared not perform his duties as the instructor. More about this: Case Study T-38 70-1956.

4

Example: A "nobody" who can kill you

In 2018 the owner of a small charter company decided it was time to take his Falcon 50 out of its four year storage so he could make money off of it. There were several problems. First, he didn't have any pilots qualified to fly it. Solution: he would fly it even though he was just a private pilot and he would hire other pilots to fly with him. On the day of his last flight in the airplane, he hired a pilot who was typed in the aircraft as an SIC only. Second problem: the aircraft had failed several test flights for several discrepancies, including faulty brakes. Solution: He talked his Director of Maintanance (who was also his son) out of the test pilot's write up by saying, "the brakes are fine." Third: he would have to avoid FAA oversight. Solution: there was no oversight.

The pilot he used for the test flights was smart enough to switch the anti-skid system off after they had failed and bring the airplane to a stop. The owner-pilot witnessed this all four times. Then, when it came time to fly the charter, he put the SIC-only pilot in the left seat and he sat in the right seat as the left seater didn't know what to do when the brakes failed. When asked about the owner-pilot's qualifications, the pilot used for the test flights said he just assumed the owner-pilot was qualified. I am betting the SIC-only pilot made the same assumption. Both pilots died and their two passengers were injured.

More about this: DA-50 N114TD.

5

How to overcome the defacto authority gradient

No matter who you hold responsible for any of the three example incidents, it is clear that these instructors were in impossible situations. It is easy to say in hindsight, “I would have taken the airplane, damn the consequences!” The few times I’ve found myself there, I could see the scenario unfold and usually rationalized it would all work out. It usually did. That made me worry about the next time. If you find yourself as the PIC flying for an owner-pilot or a defacto owner-pilot, you should think about what you hope will never happen.

- Treat the interview as going two ways. If you are being interviewed for a possible position or even for a one-time flight, you need to be sold on the operation just as they need to be sold on you. If it seems like a poorly run flght department, it probably is. If the guy doing the interviewing is also the owner, beware that his profit motive may overpower his safety motive.

- Establish the ground rules. If you find yourself flying with an owner-pilot or other defacto` owner-pilot in the role of instructor or the pilot-in-command for insurance or other purposes, it is vital to establish the conditions of your employment before stepping into a pilot’s seat. “You are obviously highly qualified in your own right, but I am here because of specific and relevant experience, training, and proficiency. I will do my best to avoid getting in your way but if I perceive the need to speak up, I will. If I direct you to take an action or to relinquish control of the aircraft, I expect you to do that. We will not argue in the cockpit; we’ll put the aircraft on the ground safely where we can debrief everything.”

- Provide latitude while being diplomatic. If you look upon the pilot you are paired with as a novice student who wants to do well but needs to learn by experience, you will have the right mindset. The pilot’s action may not be in any textbook, but if you can safely allow the situation to play out, you might have a great learning opportunity.

- Frame the issue as a problem of “your personal limits.” Many headstrong pilots have given up their integrity in increments, with small violations growing to larger ones. Because they’ve gotten away with their behavior thus far, it is impossible to argue “you can’t” because they have; you have to characterize the limitation as your own and not theirs. “I know that can work sometimes, but not all the time. I can’t do that because it is outside my limitations.”

- Draw the line. If the owner-pilot refuses to budge from their intended action, make it known that this will be your last flight in their employment. Depending on the severity of their actions, you can also say that unless they desist, you will be contacting the FAA and the insurance company.

The few times I’ve been put in similar situations and refused to go forward, my peers would ask, “aren’t you afraid you will be fired?” My answer has always been, “fired and alive to look for another job is better than not fired and dead.” Oh, by the way, I was fired once. But I am still here writing about it.