“There I was, at 30 West with one engine on fire, the other engine about to quit, and a load of passengers wondering why the cabin lights had gone dim. The number of questions was adding up, but the number of answers remained steady at nil. The only thing certain was the altimeter, which was unwinding itself quickly as we held on to whatever airspeed we still had.”

— James Albright

Updated:

2023-04-01

So goes a recurring nightmare of mine, either a product of all the simulator time in my logbook or the few times where one element or another of the dream happened in real life. In any other profession, these kinds of dreams could be part of a neurosis, a mental condition caused by anxiety and stress. But since I am a pilot, I consider these dreams to be nothing more than “chair flying,” mentally preparing myself for what I hope never happens.

While instructing pilots about abnormal procedures when flying in remote or oceanic areas, I find it helpful to do the “there I was . . .” routine. While it would be impossible to cover every possible scenario, two that I’ve seen over the years may serve to illustrate a few helpful concepts. So . . .

1 — “. . . there I was, the cabin filling with smoke and nothing but open ocean in front of me.”

1

“. . . there I was, the cabin filling with smoke and nothing but open ocean in front of me.”

It was an almost routine flight, from Anchorage, Alaska to Honolulu, Hawaii. We were flying an Air Force Boeing 707, what we called an EC-135J, with about twenty Navy passengers and an Air Force crew of ten, including three mechanics. It was a fun week in Alaska, but now everyone looked forward to getting back to Hawaii. We had been airborne for almost 30 minutes, and I was getting ready for my oceanic duties as the crew’s copilot. Something was nagging me. Oddly, the air felt and tasted oily. I immediately suspected the engines, but the gauges looked perfectly normal. I was about to say something when the navigator beat me to the punch: “Fire!” I turned in my seat and saw the cabin filled with dense, acrid smoke. Everything within a few feet of the ceiling was “WOXOF” (ceiling indefinite, visibility zero) but below that it was clear. Now what?

“I’ll turn us back to Anchorage,” the pilot said, “you get back there and figure it out.” I unstrapped, not having a clue what I could do. My first thought was the galley, which was right behind the cockpit, but the steward was seated, and his ovens were off. He shrugged his shoulders, as if this was just another day at the office. I could see the smoke spewing from an overhead duct. I doubled back and turned off the engine bleeds. The smoke stopped almost immediately but I knew our old airplane’s cabin leak rate meant our ears would soon be popping. One of the mechanics came forward and said the smoke was almost completely gone but so was our pressurization.

We had to dump over 100,000 lbs. of fuel, but thirty minutes later we were on the ground. Later that night at the bar, the second guessing began. “The pax are unhappy,” our steward reported. “One of the mechanics complained to them that we didn’t need to turn back as quickly as we had, we should have isolated the bad engine by turning the bleeds on one-by-one. Then we could have made it home on the other three.” The pilot’s face reddened. “Better safe, than sorry,” I offered. He brooded for the rest of the night, thinking word of our divert would filter to the squadron as us prematurely aborting the mission.

The next morning, we met for breakfast and the pilot greeted us with a hearty smile. “Well, we done good after all,” he said. The base’s maintenance shop found that an oily rag had somehow been ingested by the air cycle machine and the fire was contained to our air conditioning pack and was only extinguished once all the bleeds had been cut off. We only had one air conditioning pack and once that was shut off, all other options were out of the question. The divert, it turned out, was our only option.

Sometimes the only option you have is to head for the nearest runway and land

These “no other option” decisions turn out to be the easiest to make but sometimes the hardest to execute. I think a fire of any kind, the loss of an engine on a two-engine aircraft, or a flight control problem that leaves you with any doubts about the aircraft’s air worthiness are examples of when the right answer is to quickly turn your air vehicle into a ground vehicle so someone else can sort it out.

2

“. . . there I was, our ETP ahead of us but the situation wasn’t anything we had trained for . . .”

Almost twenty years ago (2003) our attitudes about drift down were more, shall we say, self-centered. “We are the emergency, everyone else can get out of our way.” We taught that if an engine were to fail, you set a specified maximum thrust on the operating engine, allow the speed to decay to a speed calculated to maximize your forward distance, and then you descended at that speed. If you were past the Equal Time Point (ETP) – the position along your route that results in an equal time continuing forward as the time turning around – then you pressed on. Otherwise, you turned around. I think most of us today know the decisions are rarely this cut and dried, but back then, I believed the popular theory. But then I was faced with reality.

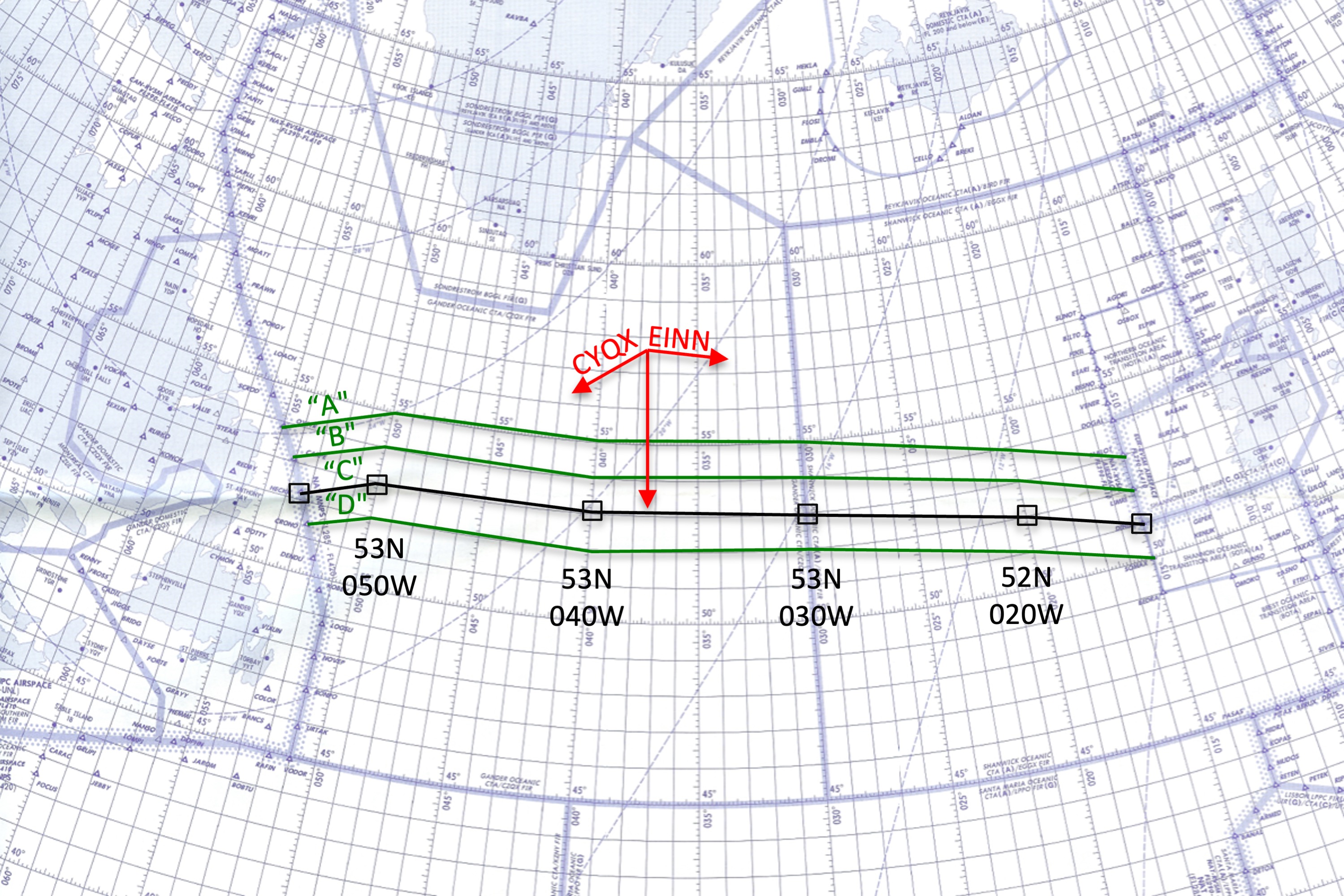

We were flying a Challenger 604 from Europe back to the United States at Flight Level 360 on the North Atlantic Track System (NATS), with airplanes above, below, and to either side of us. Our company allowed us to plot a single ETP if the engine out, remain at altitude (medical), and pressurization loss ETPs were within 100 nautical miles of each other. That was the case on this flight, and our ETP was at 53° 05.0’ North, 37° 17.3’ West. Passing the infamous 30 West waypoint, we made the necessary switch to Gander Oceanic on our High Frequency radio and busied ourselves with the many checklists triggered by waypoint passages. I briefed the other pilot that our ETP was still in front of us and that if we had any problems, the plan was to turn 180° back to Shannon. We would drift down in the turn if we lost an engine, complete a rapid descent if we lost pressurization, or remain at altitude if we could. “Obviously,” my fellow pilot said. “Obviously,” I agreed.

Back then we were required to take wind and temperature readings at each halfway point between waypoints and I was doing just that when an engine indication turned amber, letting us know one of our engines was vibrating excessively. The FAN VIB readout showed the left engine at 3.5 Mils, well above the 2.7 Mil limit. I pulled out the Quick Reference Handbook (QRH) and read. The Fan is the first set of blades in the engine compressor section, and the largest. An excessive vibration risks separation of a blade with risk to the fuselage and the rest of the engine. The procedure called for us to reduce the throttle until the vibration was in limits. I did that, resulting in enough thrust loss that our Mach Number decreased from our filed 0.80 Mach to 0.76 Mach. The procedure also called for the engine to be shut down if there were any other abnormal engine indications. There were not.

“Back to Shannon?” my fellow pilot asked. I stared at our plotting chart, which clearly indicated the ETP was still almost a hundred nautical miles in front of us. “Give me a moment,” I said, “I need to think about this.” I considered that turning around at this altitude would take us about 25 nautical miles left or right, almost halving the distance between us and any aircraft on the next track and increasing the risk of running into an airliner carrying hundreds of passengers for the sake of the three we had onboard. But I also thought about losing the engine and wanting to minimize my distance to a runway should that happen. But how much distance would be taken by the turn itself? Looking at the plotting chart, I thought that we might end up taking longer turning around than pressing forward. Finally, I looked at the engines, both of which seemed to be operating fine, albeit one at a reduced thrust setting. “Let’s press on and let Gander know we have to slow down,” I said finally. “I’ll phone a friend,” using a phrase from a game show popular at the time.

I picked up our satellite phone and called our mechanic, who asked for a few minutes to speak with the good folks at General Electric, the engine manufacturer. A few minutes later our mechanic called back. “They’ve been seeing more and more of this lately,” he said. “They say there is a coating on the fan blades that sometimes delaminates and causes these indications. There isn’t any increased risk of the engine failing. Just keep the engine at or below where you have it and bring the airplane home.”

Sometimes the best decision is to delay and consider your options.

In some cases, a diversion decision needs to be made quickly because fuel and altitude are robbing you of time. In other cases, the best decision might be procrastination. A mid-oceanic diversion carries with it added risks that must be considered. Will drifting down put you into the path of another airplane? Do your ETP fuel computations consider the winds at lower altitude or any abnormal fuel burns that have taken you off your planned numbers? If the decision doesn’t have to be made immediately, perhaps it shouldn’t. Many in the Air Force used to say, “Flexibility is the key to air power.” To that I would add, “Procrastination is the key to flexibility.”

3

The Divert Decision

There are two, almost primal, motivations tugging at us when faced with a divert decision. As mission-oriented pilots, we want to press on to the destination. This isn’t “get home-itis,” it is mission accomplishment. But we are also highly trained to think in terms of action-reaction scenarios. “In case of ____, I will do ____.” Both instincts serve us well, until they don’t.

In the case of a cabin fire, a structural failure, or any scenario where the ability to fly the airplane is in doubt, an immediate action may be necessary and the divert decision becomes easy. But for most situations, the right answer could be to take a breath and consider your options. It’s just like we used to say back in the days when bad things happened in the air almost routinely:

Question: “What’s the first thing you should do in the case of an inflight emergency, and when should you do it?

Answer: “You should do nothing, and you should do that immediately.”