By the time I got out of the Air Force, I had twenty years of leadership training both as a leader and a follower making observations of those in the front of the line.!

— James Albright

Updated:

2017-01-25

Since then, I've had several opportunities to lead a few civilian flight departments and each was rewarding in their own way; but the non-leadership experiences provided even more by way of an education. Very few civilian chief pilots or directors of aviation really have any training at all and the results can be spotty. I've seen very good leaders come out of the "school of hard knocks," but also some very poor leaders.

I've drawn up a composite of these into a fictional company I will call "The ACME Paper Clip Company." Each of the characters that follow are composites of several people. Most of the situations happened as portrayed, but I've changed locations, aircraft, and other identifying characteristics to protect identities. My intent here is not to hurt feelings or settle scores; my only intent is to provide leadership lessons by way of telling a few stories. I hope they are of some use.

While you shouldn't approach a leadership position with the idea you are at war, Sun Tzu's The Art of War provides excellent lessons that seem to apply in many of these situations in the first chapter that follows. For the second chapter, the lessons are my own.

1 — The ACME Paper Clip Company, Chapter 1

1

The ACME Paper Clip Company, Chapter 1

2000 to 2001

I retired from the Air Force without a plan, but a callout of the blue led me to the ACME Paper Clip Company. An ex-squadron mate of mine assured me it was a good flight department, flying good equipment, with a very good trip schedule. Ryan Nelson and I were about the same age, but he had punched out of the Air Force early, so he had a headstart in the civilian world.

"How's the leadership?" I asked.

"The boss is ex-Air Force," Ryan said. "He flew B-58s in the sixties and retired as a lieutenant colonel. He has lots of war stories."

"But how is his leadership?" I asked.

"About what you would expect," he said. "I've seen better, but I've seen worse."

I interviewed, the new boss seemed okay, and I took the job. Chief pilot Harold Prestwick was in his very late fifties and had the beer gut one would expect in such a seasoned pilot from his era. I marched off to Challenger 604 school and came back a copilot, ready to learn how to fly as a civilian.

The Long Day

Pilot Count: 4 international captains, 2 domestic captains, 2 first officers

I was the eighth pilot of eight total. Harold, Ryan, and I comprised the Air Force contingent. The deputy chief pilot, Gerry Winters, was a retired Army pilot. The other four were all pure civilians. Of the group, Ryan and two of the civilians were very good. I had my doubts about everyone else, especially Gerry.

The ACME Paper Clip Company CEO grew up in Rome, Italy and was trying to establish an Italian outpost for paper clips. It was one of our most frequent destinations.

"How can we do a 16-hour day when the book says 14 is our limit?" I asked chief pilot Prestwick.

"Well we used to do Paris in one, 14-hour day okay," Harold explained. "When the new CEO asked for Rome, it didn't seem to be that much extra."

"But the book says we need to preposition a crew for something this long," I said. "We could airline a crew to Boston."

"Well I thought of that after the fact," Harold said. "But it's too late now. We've already established the precedent."

I flew the trip with Gerry and showed up in Rome exhausted. For the return trip we were bucking headwinds and somewhere around Kentucky I nodded off. When I woke up, Gerry was sound asleep in the left seat and air traffic control was wondering why we hadn't answered any radio calls for five minutes. The next morning I marched into Harold's office and refused to fly the trip again.

"How am I going to ask anyone else to fly this trip if I give special treatment to you?" he asked.

"Sending anyone on this trip is the classic example of a 'careless or reckless' operation," I said. "You are really hanging it out here."

The next trip to Rome included a crew change in Boston. Harold handed me my upgrade papers, appointing me as captain for the leg from Boston to Rome, and told me I would have to endure the CEO's ire when he discovered two new pilots and a flight attendant had airlined to the east coast. I flew the trip and if the CEO noticed at all, he didn't say anything.

The Short Runway

Pilot Count: 5 international captains, 2 domestic captains, 1 first officer

I settled into a routine of flying mostly international trips while Gerry and a few others seem to prefer the domestic hops. The few flights I had with Gerry were tests in patience. He seemed to fly by his own rule book and the results were often spotty. Even after being dressed down by an air traffic controller or confronted with bald tires because of a mishandled landing, he always managed to blame someone else.

Our Italian CEO, I found out, had a passion for golf. Gerry and I were scheduled to fly him to Hilton Head Island Airport, a new location for me.

"This runway is shorter than our book allows," I said to Gerry after I found the trip sheet in my email. "Savannah is just a few minutes away."

"The boss has already waived the rules, and we've been doing this for more than a year," he said. "Don't you Air Force boys know how to follow orders?"

Gerry flew us to Hilton Head and followed an unstable approach by an unstable landing which he planted on the first inch of pavement. The aircraft bounced and we finally came down again with 1,000 feet of the runway's 4,300 feet behind us. "Damned wind shear!" he said as we finally came to a stop.

"I'm never doing that again," I said.

"You better start looking for a job then," he said.

I came back from the trip and had another talk with Harold. He listened quietly. "What am I supposed to do?" he asked. "If you say no to Hilton Head what do you think the other pilots are going to say?"

"If they had any sense, they'll say no too," I said.

And that's what happened. With only Harold and Gerry willing to fly into Hilton Head, he had no choice to start scheduling us into Savannah instead. I flew the CEO on his next golf outing and he asked why we didn't fly into Hilton Head Island. "The runway is too short," I said. "Savannah is safer for this airplane."

"Oh," he said. "Well, I just want to be safe."

The Short Fuse

Pilot Count: 5 international captains, 3 domestic captains

"Declare an emergency," I said from the left seat. "Get us vectors to Berlin Schoenefeld."

"Are you sure you want to declare an emergency?" Frank asked. "Gerry is going to go ballistic if he finds out."

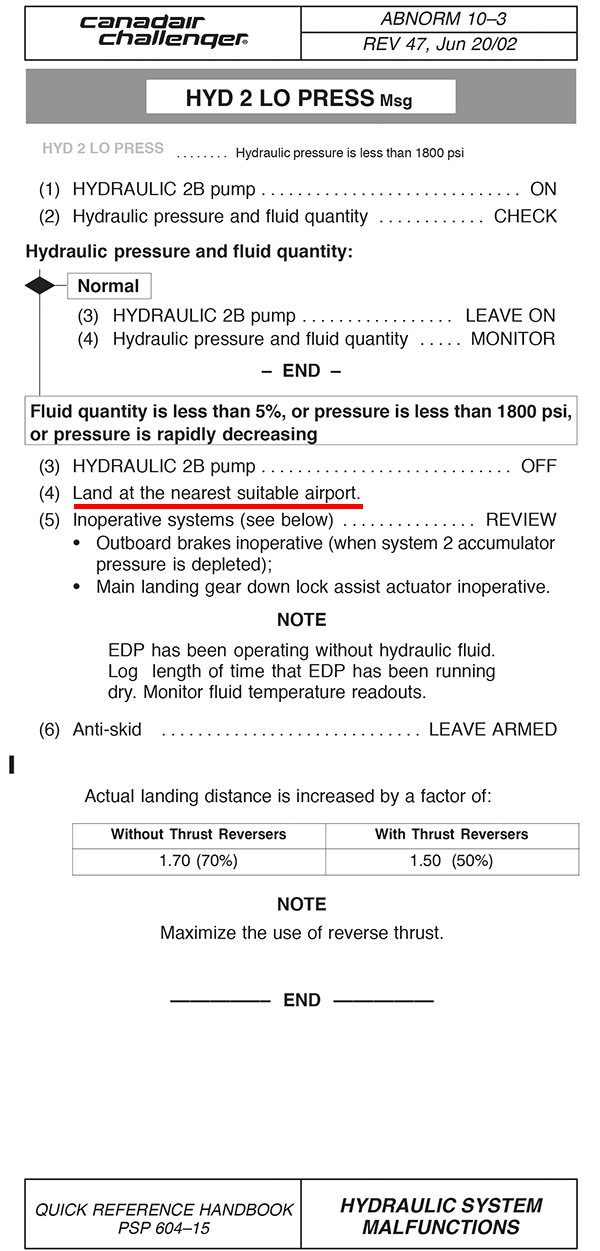

"Let him," I said. Frank was an adequate pilot but a little timid. Our number two hydraulic system had failed, leaving us with two of the original three. The redundancy left to us was okay, but the situation clearly called for an emergency landing. We ran through the checklists and satisfied ourselves that we were ready to get the airplane on the ground.

"What was that?" I asked.

"What was what?" Frank asked.

"I saw a red CAS message," I said. "There it is again." The Crew Alerting System was giving us intermittent warnings which grew in frequency and then duration. For a while we lost our SATCOM radios, then a pressurization computer. "I saw a brakes message," I said. And then it came again, an anti-skid warning. By the time we landed the stack of messages exceed the number of lines on the CAS.

"You want to hold and sort this out?" Frank asked.

"We have three green gear indicators," I said. "At least one of the brake systems is working. None of those other message make any sense. I think we must have a computer problem. Let's put the airplane on the ground, test the brakes, and if they work stop the airplane."

"Yeah, that makes sense," he said.

The airplane handled and landed fine. Schoenefeld, to our surprise, had a Canadair service center and technicians descend on the airplane less than an hour after we landed. A hydraulic pump in the aft equipment bay failed and sprayed hydraulic fluid over everything in the bay, including the avionics.

It will take three days just to clean up," the technician said. "We will have to replace half the electronics and that will take another three days."

We were headed for London so the passengers booked tickets for home via England.

"Berlin?" Gerry yelled into the phone. "What kind of moron are you?" I recognized two voices in the background; it sounded like he was in the scheduling office within earshot of our dispatcher and another pilot. "The pax were headed for London, all you had to do was fly one more hour! You Air Force pilots don't know how to use that noodle between your ears!"

"Gerry, perhaps you need to take a breath," I said. "I would suggest you pick up the manual and look at the procedure."

"I won't have you talk to me that way!" he said. "The boss gets back from vacation before your airplane gets fixed. We'll see what he has to say about this."

If Harold had anything to say at all, I never heard. We got the airplane fixed and brought it home empty. On our return we found out Gerry had been fired for losing his temper, but it had nothing to do with our Berlin incident. He was on another trip and blew a fuse in front of the ACME Paper Clip Company CEO.

The favor long owed

Pilot Count: 4 international captains, 3 domestic captains

While six of us pilots and all three flight attendants decided to have a farewell party for Gerry, without Gerry, we had the good sense not to invite Harold Prestwick. Harold hired Gerry as a favor to our flight department's management company. The two became quick friends and ran the flight department as partners. No sooner had Gerry turned in his aircraft keys and badges, the management company started calling Harold with advice for replacement pilots.

"Rack and stack time," Harold announced at a rare pilot meeting. "The company has six volunteers, all of whom are ready willing and able to move here. You guys put these into order with your first choice on top."

We set upon the resumes, expecting the best pilots the company had to offer. One was an ideal fit, two were acceptable, and the three remaining were clearly unqualified. "Look at this guy," Ryan Nelson said. "He doesn't have any honest to goodness jet time. Who are they trying to fool?"

"Mark Peele," another pilot read from the resume. "He's got a couple hundred hours in a King Air. At least he has some turbine time."

"Do you want to sit in one seat while some guy who's never flown anything bigger than a King Air flies you down to minimums?" I asked.

"No!" everyone answered in unison. We ordered the list, placing the ideal candidate on top and Mark Peele on the bottom. The next day we found out Mark Peele would be joining us in a month, after going to initial qualification school.

After a month Mark was still in school. Harold called me into his office and asked that I close the door behind me. "Peele busted his initial qualification check ride," he said. "They gave him a recheck and he busted that. They say he needs to go through the course again and that's going to cost us extra. What should we do, James?"

"Cut your losses and move on," I said. "He might be a good pilot but we are asking an awful lot for someone with his background to fly this kind of airplane."

"We all got to get a start somewhere," he said.

"Sure we do," I said. "But you are asking him to fly an airplane that weighs four times as much and flies maybe forty knots faster on final approach. That's asking a lot."

"I promised the management company we would give him a shot," he said.

"He's had his shot," I said. "I don't want to fly with the guy and I'm sure I'm not alone."

"I can't do that," he said.

We paid for Mark's second qualification course and he did actually fly for us for three months.

Pilot Count: 4 international captains, 3 domestic captains, 1 first officer

Slowly, but surely, pilots started to refuse him any time flying the airplane. "Read the checklist," they would say. "You can do that, can't you?"

I tried to be more helpful but after Mark tried to stall the airplane at 31,000 feet with a load of passengers I had had enough. Mark was gone the next week.

Pilot Count: 4 international captains, 3 domestic captains

The last straw

After Gerry's departure two other pilot announced that they had reached their breaking points with him and had accepted other jobs, and were committed to leaving even though their reason for leaving was gone. Added to Marke Peele's exit, we were down three pilots.

Pilot Count: 3 international captains, 2 domestic captains

Harold hired the next three on his list of dream candidates and we set out to train each as quickly as possible. It wasn't going well.

Pilot Count: 3 international captains, 2 domestic captains, 3 first officers

"Harold, we have a problem on the Nice trip," I said. We always sent two aircraft to Nice, France for every year's running of the Grand Prix in nearby Monaco. Ryan was attending a wedding and Harold refused to ever cross the pond after being threatened during a ramp check in Paris. That left me and one of our less than reliable pilots to command the two airplanes. "Frank is okay domestically, but he's a bit lazy when it comes to international procedures. You can't send him as the pilot in command. Two of the new guys will do better."

"No, I can't do that," Harold said. "Frank's been with us for two years. I can't pass him over for a new guy!"

I followed Frank across the country and then across the North Atlantic on our way to Nice, about an hour behind. I showed up at the hotel bar about two hours after he had obviously tossed back a few. "Did you get the same bizarre arrival?" he asked as I sat down on the barstool to his left.

"Define bizarre," I said.

"We checked in with tower and they immediately started yelling at us!" his copilot exclaimed. "We were making a normal left downwind pattern entry and all hell broke loose!"

"They said we should have flown the arrival," Frank said. "Approach control never told us that! If tower should be upset with anyone, they should yell at their own approach control!"

"Yeah," his copilot said. "It's called co - mune - i - ca -shun! Don't these Frenchies know how international aviation is supposed to work?"

"Are you guys kidding me?" I asked.

"No," Frank said. "Why would we do that?"

"The ATIS called for the visual maneuvering procedure to runway four right," I said. "There is a two page approach procedure in the Jepps. It's a much wider downwind but it keeps you free from the departure path. It's actually pretty easy."

"The ATIS?" Frank said. "It was in French. We don't speak French."

"The ATIS is in both languages," I said. "You just needed to wait until the French broadcast was over."

Everyone made it back to the U.S. okay and I wondered what the French would do. We often hear about U.S. pilots being violated overseas, but other than an Air Force C-141 crew, I didn't have direct evidence of it ever happening. The French, apparently, contacted the U.S. FAA, who contacted our management company. Our management company agreed to fire the pilot in command as well as the chief pilot. The FAA, in exchange, agreed not to take any certificate action against our pilots.

Pilot Count: 2 international captains, 1 domestic captains, 3 first officers

I felt bad for Frank; he was sent into a situation he wasn't adequately trained to cope with. I didn't feel bad for Harold, however. He could have prevented the entire incident. The management company surprised me with a call the next day and asked who I would recommend to take Harold's place. "Ryan Nelson would be my top pick," I said.

"Would you follow his leadership?" they asked.

"Absolutely," I said.

2

The ACME Paper Clip Company, Chapter 2

2002 to 2003

The Intro

"They made me the chief pilot, James," Ryan said. "Is that okay with you?"

"Of course," I said. "You are going to do great."

"I'm putting together a speech to announce to everyone the change in leadership," he said. "I was wondering if I could run it by you first."

"Of course," I said.

Ryan read from a prepared speech, a bit nervously, tripping over a few paragraphs here and there. His thoughts and intentions were good, but I felt nervous for him just listening to his tortured delivery. When he was done, he looked up from his notes, expecting the worse.

"Very nice," I said. "I think you have all the right ideas, but maybe we can polish the delivery and a few of the ideas. I especially like the idea of 'safety, comfort, reliability' in terms of a list of priorities."

"I thought you would," he said. "I've heard you talk about them enough."

"I've noticed a lot of the guys kind of roll their eyes when I say it," I said. "I've probably made it trite, in their eyes."

"How do we fix that?" Ryan asked. I thought for a moment.

"Remember how Gerry Winters refused to fire up the APU until thirty minutes prior to scheduled takeoff time?" I asked.

"Yeah, and then it would be a mad scramble to get everything ready if the pax showed up early," he said. "He once took off without the FMS programmed."

"Well you could mention that as an example," I said. "His priority was saving money, but he made things less safe by having to rush through the checklists prior to takeoff. We should try to have everything ready to go, thirty minutes prior to takeoff. But if the passengers are early, we don't rush the steps. We would rather be late and safe, than on time and questionable."

"Slow down," Ryan said. "I need to write this down."

"And that's another thing," I said. "I don't think you need to give us a prepared speech at all. Just write down a list of topics you want to cover, and talk to us like we are just shooting the breeze. It will make you more comfortable speaking, and us more comfortable listening.

Ryan put down his pad and paper. "My nervousness shows?" he asked.

"A little," I said. "But that's natural. You get better at this with time, believe me."

"Am I missing anything I should be covering?" he asked.

"These kind of introductions are necessary but a bit awkward in the case of someone who needs no introduction," I said.

"Everybody already knows me," he said.

"They know you as Ryan, international captain, fellow pilot, or the guy who enjoys a good steak and a beer," I said. "But they need to get to know you as the new boss. So the way you cover safety, comfort, reliability is important. And I like the fact you say you have an 'open door policy' though you might want to just say it in other words that don't sound like you are reciting something from a 'Leadership 101' manual."

"Maybe I should just tell them they can bring anything up that needs my attention and leave it at that," he said.

"That sounds good," I said. "But we each have to tailor these things for our strengths and our weaknesses." Ryan locked his eyes on mine, ready for what might be a personal insult to come. "Ryan, you do have one weakness that you might consider addressing up front, because it could hurt you in the long run."

"My temper?" he asked.

"Yes," I said. "You don't have a bad temper, but now and then you do fly off the handle when under stress."

"We don't all have ice water in our veins," he said. "James, just because you are part Vulcan doesn't mean its normal to suppress everything."

"That's true," I said. "But if the boss becomes known for reacting to bad news poorly, he will stop getting bad news. And that leaves the boss in the dark."

"I see your point," he said. "But how do I bring that up without looking like a complete doofus?"

"I once worked for a squadron commander in the Air Force who began his tour saying he tended to be 'overly passionate' about things," I said. "But he followed that up by saying he never held a grudge and that if any of us were to catch him reacting unreasonably we were to tell him 'g-meter check!' and he would wind down. Now when he told us that I thought it was kind of hokey, but the rest of the squadron laughed and it became a running joke with him. In two years I never did see him lose his temper."

"How about this," Ryan said. "I'll just say that I know I can hit the ceiling at times, but I promise to come back to the floor so we can work out whatever the problem is together. I don't get angry at people, only situations."

"Ryan, that would be perfect," I said. "But you have to work to make that true."

"I will," he said. And he did. His opening remarks to us were short and to the point. The mechanics made a few jokes about Ryan's time spent on the ceiling in the maintenance office and everyone, including Ryan, had a good laugh.

"I think you are off to a great start," I said.

"You have my permission to knock me in the head if I ever need a course correction," he said.

Delegation

Pilot Count: 2 international captains, 2 domestic captains, 3 first officers

There is more than enough work to go around a small flight department to keep a few guys busy, but with seven pilots we had more than enough labor to get everything done. Some pilots had very simple jobs that took a few minutes a week. The most distasteful job was keeping the Jeppesen approach plate binders for both airplanes up to date. That would take several hours each week. It was a rite of passage for the newest pilot to get the task.

First Officer Tony Weston reacted to the job as most newly hired pilots would. "Anything I can do to help!" Of course this zeal diminishes with time and the amount of time given the task diminishes as well. He would bring each binder into our pilot's mission planning room and spread everything out at once. The tabletop would be a collection of ten or fifteen open binders, with new pages in stacks next to binders and old pages thrown to the floor.

"How do you keep it all straight," I asked on a particularly large change.

"I have a system," he said.

Tony was my first officer during a flight to Taiwan when he learned the price for such sloppiness. "The ILS pages are missing," I said. "I've looked all over and they are missing."

"Jeppesen must have made a mistake," he said.

"When was the last page count?" I asked.

"What's a page count?" he asked.

The weather in Taipei was better than visual and we asked for and were permitted to fly a visual approach. After we landed Tony and I checked the approach plates for each of our upcoming destinations and found ten more missing approach plates. I called the management company and had them express mailed to my hotel room in Taipei. I also found the latest page count form in one of the binders; it hadn't been completed. I helped Tony complete the form during one of our days off in Taiwan; we found another sixty missing pages.

"So I guess this will never happen again," I said. "Right, Tony?"

"You can count on that," he said.

A month later Tony came to me with the next page count form, completely filled out with only four missing pages. "Good job," I said.

"Did you hear about the flak Ryan took over this?" he asked.

"No," I said. "What flak?"

"The management company director of flight ops found out we were missing approach plates while on the road and called Ryan to chew him out," Tony said. "Ryan said it was 'our mistake,' and that we had a process in place to fix it. He didn't give them my name."

"We all make mistakes," I said. "Ryan knows that. And now you know he wants to protect his people because his people want to protect him."

Tony looked even more contrite than the day I confronted him about the missing Taipei approach plates. I never again saw the bedlam of the approach plates on our mission planning table and never again found a missing approach plate while flying for the Acme flight department.

One of the Guys

Pilot Count: 3 international captains, 2 domestic captains, 3 first officers

For a brief moment in time, Ryan's reign over the flight department was as royal as the word "reign" would connotate. We, the troops, were happy to be done with the limp-wristed leadership offered by Harold Prestwick. We were even happier to have avoided the possibility of a strong-armed takeover by Gerry Nelson. The troops were happy to follow Ryan, who ably led us while he could. Circumstances would eventually doom us to failure, no matter who held the reins -- yes, those kinds of reins -- but for about six months things were good.

Our two airplanes rarely found themselves in the same city unless both the CEO and COO were destined to fly at the same time. ACME Paper Clip Company rules would not allow both on the same airplane; it had something to do with the highly competitive world of paper clip sales around the world. Nevertheless, we started flying two airplanes more and more often to China, quite often with the COO on one airplane, the CEO and his body guard on the other. Our crews were becoming proficient at getting into and out of Shanghai, Hong Kong, and Taipei. It had been six months since Ryan gave me permission to "knock me in the head" for any course corrections. But his course had been flawless until Shanghai.

Our two aircraft arrived at Shanghai Pudong International Airport within minutes of each other. We left the airport in separate vans but made it to the hotel at the same time. We strolled into the Shanghai Marriott Hotel minutes apart too, as if part of a precision aerial demonstration team. Finally, we all showed up at what was supposed to be the largest Scotch Whiskey bar, within seconds.

"Too bad Frank isn't here!" Louise said. "That boy can inhale a bottle of Scotch like nobody's business!"

And so the topic of the night became one our pilots who wasn't present. Frank was a sloppy pilot, a sloppy human being, and a sloppy drunk. But he didn't deserve to be the subject of a knife in the back competition taking place on the opposite side of the earth. I kept quiet but two of the pilots and the two flight attendants were trying to outdo each other with "Drunk Frank" stories. Finally Ryan offered a story of his own, and it was hilarious.

"Can we have a word?" I said, holding my cell phone to my ear, feigning a phone call I had not received. Ryan followed me to the lobby.

"You ready for a course correction?" I asked.

"Was my Drunk Frank story over the top?" he asked.

"It was a funny story," I said. "In fact, I might be tempted to use it years from now, away from this flight department. But you can't."

"Why is it okay for you and not for me?" he asked.

"Because I am one of the troops," I said. "You are not. If Frank hears that two crews were laughing behind his back, that's between us guys in the trenches. If he hears that one of the guys was you, that's different. You don't even have to be telling the joke. If you even laugh at the joke that's going to wound him in a different way. You aren't one of the guys. What you say, what you laugh at, it is different."

I wondered if I had gone too far. I had known Ryan for over ten years and had never presumed to lecture him about anything, much less his job. And yet there I was.

"I see your point," he said. "Frank is a nut case, though. Between you and me."

"He's a lunatic," I said. "Between you and me."

Upgrading Tony

As our Texas winter gave way to Texas spring, the ACME Paper Clip Company announced it was being bought out by a Chinese paper clip consortium. We as a flight department would have another year of flying and, if we were lucky, might find jobs with the new company in Beijing. Two of our most senior pilots found jobs within the week and were gone within the month. And it was going to get worse.

Pilot Count: 2 international captains, 1 domestic captains, 3 first officers

"What do you think about Tony as a captain?" Ryan asked.

"He's not ready," I said. "He doesn't know the airplane the way he should, his decision making is poor, and he doesn't have a clue about how to run a crew."

"He's better than the other two first officers," Ryan said.

"That's true," I said. "I still wouldn't upgrade him."

"I don't have a choice," Ryan said.

Of course Ryan was in an almost impossible situation. We were in a dying flight department where no sane pilot would want to work, knowing the job would soon go away. He decided to upgrade Tony and only pair him with other captains in an attempt to season him. But even with the captain title, Tony tended to defer to the more experienced pilot in the other seat. I was so busy flying overseas that I lost track of the situation.

Pilot Count: 2 international captains, 2 domestic captains, 2 first officers

In the coming weeks Tony was racking up domestic trips uneventfully and starting to think of himself as a captain. The mechanics complained about the condition of the brakes and tires whenever he returned from a trip and the flight attendants would complain about his demeanor away from home base. Ryan counseled him a few times but had settled into a routine where we were able to put forward one aircraft and crew for international operations, the other for domestic. Tony had become "Mister Domestic."

The next time I saw Tony was during a crew swap in Bedford, Massachusetts. He flew the airplane from Houston for a midnight refuel and crew change. I would take the airplane to Geneva.

The weather to the west was awful and I was prepared for a late night. Weather over the North Atlantic was fine. The airplane arrived almost on time and the FBO decided to park it away from the main ramp, since none of the passengers were deplaning. The fuel truck got to the airplane before my crew and the catering. As the door opened a pilot I didn't recognize was helping the flight attendant down the stairs. Louise looked ashen and unsteady on her feet.

"Are you okay?" I asked.

"She'll be fine," the pilot said.

I got to the cockpit where Tony was finishing up on the airplane forms. "Good airplane," he said. "No worries on our end, have a good flight to Europe."

"What happened to Louise?" I asked.

"Oh she always has something to complain about," he said. "Typical flight attendant."

"Who was the pilot you flew with?" I asked.

"Oh that was Darrel," he said. "Good guy, contract pilot."

The airplane was fueled, the passengers were ready, and we departed into the black sky. We refueled again at Gander and ended up in Geneva about noon, Switzerland time. As I left the airplane and looked back I stopped dead in my tracks. The radome had lost half its paint, as if it has been peppered by rock salt from a shot gun. There were no visible dents and the rest of the airplane looked fine. I called Canadair and arranged to have a mechanic inspect the airplane for hail damage and run any severe turbulence checks they could. My next call was to Ryan.

"How is Louise?" I asked.

"She's in the hospital in Boston," he said. "She says she can't make the return leg so we are sending a contract flight attendant to take her place. She said they had a little turbulence on the way into Bedford. But all of the passengers were belted. She was the only one hurt."

"I think they must have flown through a thunderstorm," I said. "The radome looks like its seen a fair amount of hail."

"Tony didn't say anything about a thunderstorm," he said.

Canadair spent two days on the airplane before finding a crack in the ring that holds the copilot's windshield in place. That took two days to replace. The passengers took an airline flight to their next stop in London, where we hoped to catch up with them. The damage to the window frame was superficial, so slight I hadn't notice it until the mechanics pointed it out. It could have been worse.

"You lied to me," I said to Tony over the phone. "You told me you had no worries."

"Just a little turbulence," Tony said. "It was no big deal."

"Our passengers told me Louise was thrown to the ceiling," I said. "That qualifies as severe turbulence in my book. The airplane should have been grounded."

"You are over-reacting," he said. "I would have flown the airplane on to Europe without a second thought."

"That's because you don't know what you are doing," I said. He hung up the phone.

A week later we were back in Houston and Tony was gone. Our dispatcher said Ryan called him into the office and calmly told Tony he was revoking his pilot in command, PIC, status. Tony quit.

Pilot Count: 2 international captains, 1 domestic captain, 2 first officers

"Did I go too far," Ryan asked, looking at our decimated pilot scheduling board.

"I would have fired him," I said. "But in the end we have the same result. How has the fall out been?"

"Acme is unhappy," he said. "But they are going to end up with a one-hundred-percent contract pilot force in the end. They might as well get used to it."

"The mechanics were talking about what a cool cookie you are," I said. "They said you never once raised your voice, even though Tony raised his. The only problem we are going to have now is if Louise takes us to court."

But in the end, she didn't. Louise got better but decided she had enough of flying. Smart woman, she.

Hiring / Firing and Firing / Hiring

"Nobody good wants to join a flight department for just a year," Ryan said while looking at a stack of resumes. "Anyone willing to send in a resume is probably a reject from someplace else."

"I would think that point is self evident," I said. "I suppose you can lower your sights a little. We can't attract the best, but we shouldn't hire anyone we don't think can meet a minimum level of safety."

"And who decides what that level is?" he asked.

"Technically that would be Acme and the management company," I said. "But practically, it is you. You are running the show and if you aren't comfortable putting your kids on an airplane with a pilot, you shouldn't be putting our company's executives in that situation either. Acme has to realize they are going to end up with an all contract pilot flight department before end."

"The management company is able to keep us supplied with contract pilots for the rest of the year," Ryan said.

"The only question is what are we going to do when we run out of PIC-qualified pilots?" I asked.

"No, there is another, more immediate question," Ryan said. "Fred has been hitting on the flight attendants lately. Against their wishes. I've counseled him with no results. I think he might be hitting the sauce pretty heavy on layovers."

"It would be a shame to lose a PIC," I said. "Fred is basically a good guy but he's got personal issues at home. If his head isn't in the game he shouldn't be flying, especially given the fact our first officer bench is so thin."

"How can I fire a guy when we are so undermanned as it is?" Ryan asked.

"I think the management company has an alcohol abuse program," I said. "Fred is no use to us in the cockpit, but there are steps short of dismissal."

Ryan contacted the management company who contacted Fred. Fred was furious and left his airplane keys, badges, and his company computer on Ryan's desk with a Post It note with two simple words, "I quit." A week later he was hired by another operator at another Houston area airport.

The End Game

Pilot Count: 2 international captains, no domestic captains, 2 first officers

"Ryan, I found a job out east," I said. "They are willing to wait a few months for me, but the job is mine for the taking immediately."

"Go now," he said. "I found a job up in Dallas. I'm giving them two weeks notice."

"Two weeks?" I said. "That isn't a lot of time, is it?"

"Well I think they were going to fire me if I stuck it out any longer," he said. "I've been turning down half their trip requests. They think I'm doing a lousy job."

"You did a good job insulating us from all that," I said. "You have a lot to be proud of."

"I sure don't feel that way," he said. "But in the end your words to me a year ago have stuck. If we can't do it safely, we shouldn't be doing it at all."

"What about the copilots?" I asked.

"My new company will hire them both if they want to move up to Dallas," he said. "It's time to turn out the lights."

Pilot Count: None

Appendix

Source notes

There are five dangerous faults which may affect a general:

- Recklessness, which leads to destruction;

- cowardice, which leads to capture;

- a hasty temper, which can be provoked by insults;

- a delicacy of honor which is sensitive to shame;

- over-solicitude for his men, which exposes him to worry and trouble.

Source: Sun Tzu, pg. 22

We often define "reckless" in terms of 14 CFR 91.13 but can encompass more than just placing the airplane in harm's way via stick and rudder. Sometimes the most reckless actions happen at the scheduling board.

We don't often think of our Point A to Point B aviation careers in the warlike terms of "bravery" and "courage." But we are often called upon to issue the simple word "no" to those we work for. Yes, it takes bravery. And yes, it is a sign of cowardice to shrink from that duty.

We wouldn't be pilots if we didn't have egos; but sometimes those egos can get the better of us. We have a difficult time recognizing mistakes and when we do, we either obsess over them or go into denial. If a leader fails to learn from mistakes he or she risks repeating them or stumbling upon new variations of the same mistake over and over again.

One of the most common mistakes of a new leader is an attempt to remain "one of the guys." Everyone wants to be liked to the point of making compromises to please the masses, but a leader cannot afford this luxury. There is nothing with a leader who is liked by his or her subordinates. But a leader who sets out with this as a goal is making a mistake.

More notes

Taking Over (Avoid getting started on the wrong foot.)

If the group doesn't know you, introduce yourself. Portray yourself honestly but in a positive light. Give them a glimpse into who you are, as you would like to be known and as you believe you can be, then work towards that goal. But don't be unrealistic; if you fail to reach your ideal self you will be quickly revealed as a fraud.

If the group does know you, be honest and humble. If you recognize glaring faults in yourself that others are sure to know about, acknowledge these, promise improvement, and solicit help. "I know I've been a little short tempered at times, but we all know what a mad house this can be! So, with your help, we are going to work to keep things on a more even keel."

Avoid trite sayings that convey little and can seem phony. "I will have an open door policy and with me, I care more about what's wrong not who's wrong!" Instead, speak from the heart about the important issues and . . .

Outline a vision for the group that includes an easily understood (and short) list of priorities. Provide a road map on how to accomplish these priorities. For a flight department, I recommend:

- Safety. "There is nothing more important than keeping things safe; if you ever have to make a decision that costs money, harms the schedule, or does anything contrary to other goals, but it is necessary to keep things safe, you will have my full and unqualified support."

- The Book. "We should aim to fly 'by the book' and if that isn't possible, we should change the book to reflect the way we fly. That keeps us all operating the same way, it keeps us in compliance with all those government agencies keeping an eye on us, and it keeps us focused on the job at hand.

- The Job. "We are here to support our passenger's needs, to get them to where they need to be. That's why we are here, after all. But we cannot risk their lives or violate any laws trying to do that. If you find yourself in a situation where you are being asked to compromise safety or regulations to satisfy a customer request, don't do it. Call me and I will have your back."

- Your people. "We are all professionals here and this is not likely to be your last job in your distinguished careers. We are all destined for bigger and better things. So we are all here learning, me included. Let's keep an eye open for career growth within and outside of the flight department. If you ever find yourself feeling at a dead end or in need of a new challenge, let me know. We can fix that!"

Delegation (Authority, not responsibility)

No leader can do it all; a leader who tries to do it all fools himself and alienates his or her followers. Sharing the duties frees the leader to concentrate on other things, telegraphs a sense of trust to the followers, and helps develop the followers into future leaders.

A leader must be willing to pass praise and credit to those doing the work, without a need to share in the glory. A leader must also be willing to accept the blame for mistakes, without having to deflect any of that to the follower. This type of selflessness is hard to practice at first, but it gets noticed by those above and below. But even when it goes unnoticed, the leader must persist in this pattern. Doing so will be hard at first, but it becomes easier and natural.

Camaraderie (You are not "one of the guys.")

Once you take on the role of leader you forever give up your membership to club "we." Any attempt you make to be "one of the guys" diminishes your role as a leader and can cause a conflict if and when your responsibilities require you to act for the good of the organization against one of those "guys."

Limitations (Knowing when to say 'no.')

As pilots we know the price of violating a flight manual limitation can be damage to the airplane or loss of life; we take these things seriously. But in a bureaucratic environment, we often fail to rationalize these same limitations or others than have nothing to do with airplanes, as mere paragraphs to be worked around. But even a non-airplane limitation can have dire consequences.

The difficulty with considering a limitation outside the cockpit is we are usually confronted with the threat of failing to meet job expectations. But even these must be weighed against the safety of the aircraft, its occupants, and the operation itself.

One of the hardest things for a leader to do is to say 'no' when given an assignment. But when dealing with flight operations, 'no' is quite often the only acceptable answer.

Firing and Hiring (When to pull the trigger.)

It is easier to hire than fire, but hiring poorly can doom one to having to fire poorly as well.

Headquarters (Dealing with those who sign your paycheck.)

It is easy to list the first two priorities in any operation: keep things safe, and keep things legal. But the next two items compete with each other for the next position: satisfy the needs of your bosses, and satisfy the needs of your people. If you put too much priority on one at the expense of the other, you could lose both.

References

(Source material)

Tzu, Sun, The Art of War (in the public domain, the author lived between 544 BC and 496 BC.)