The week before I was to assume command of an Air Force flying squadron, I was presented with a sealed letter with instructions to "read this, then burn it." It was a collection of 13 inspector general complaints against my predecessor from the men and women of the squadron. The complaints were so compelling and obviously true, the Air Force offered this lieutenant colonel — let's call him Clevis Haney — a choice. He could accept an early retirement or face the charges in what could very well end up with his imprisonment. What choice did he have?

— James Albright

Updated:

2017-01-09

I read the charges, took a few notes, and burned the copied reports as instructed. In the year that followed, I found each of the 13 charges could be categorized into one of several leadership styles gone awry. I also found many of my fellow commanders had varying degrees of success with these leadership styles.

As I write this, 20 years after the fact, I realize that many of the lessons can actually be extracted from The Leadership Secrets of Genghis Khan. Yes, that Genghis Khan. Notice that every trait has a positive and a negative side. We can be blinded by the positive so much that we forget the negative. I also make reference to Air Force Colonel John Boyd, whom I think of as the finest officer to ever wear Air Force blue. I've also provided many of his written works in the references below.

Please keep in mind I have changed the names for each of the characters that follow and in some cases I threw in a few curve balls (I combined characters) just to keep identities safe. I don't want to hurt anyone's feelings and the goal here is to tell stories with leadership lessons built in. With one exception, none of these people are evil. Each set out to do the job placed on their shoulders given the leadership qualities they had. Most were like me, with a background in leadership founded on classroom and observation. And most, like me again, were in the "learn mode," trying to improve whatever leadership skills they started with. But most, including me, had faults that may have been a byproduct of their strengths.

I also allude to the crash of the CT-43, the Boeing 737 carrying several White House passengers into Dubrovnik, Croatia. I know what happened and, more importantly, I know the flaws in the official accident report that so many have used to slander the flight crew with. I reveal this in book, Flight Lessons 4: Command. But for now, I'll just touch upon the leadership styles of a few of the key players.

Yes, this is a long one. It is a story I used to tell with the title:

Thirteen Strikes Against Clevis Haney

1

Charismatic

Hero status for pilots is a part of military tradition from its earliest days. Starting with World War I German ace Manfred von Richthofen, the "Red Baron," fighter pilots earned a mystique among the populations of their own countries as well as their enemies. This phenomena only grew with subsequent air wars, perhaps ending with Vietnam. From that point on, U.S. Air Force pilots have been schooled about the exploits of Captain Steve Richie and his five confirmed kills. But since then? Captain Richie was the last.

By the time I showed up at Ramstein Air Base, Germany, in 1994, the day of the fighter pilot ace was already over. We had learned how to obtain air superiority using long range missiles and there was no longer a need to risk pilots to get it. But the Air Force still inculcated the hero worship for all things around the steeley eyed fighter pilot.

My first task while reporting for duty as a brand new squadron commander was to meet the wing commander, General Lesley Remington. His reputation preceded him. He was a command pilot with over 4,000 hours in the T-37, T-38, F-4, and F-16. He spent a year in Thailand during the closing days of Vietnam and then had tour after tour in Europe which culminated with his command of the 86th Wing at Ramstein. He was a charismatic and popular leader. Though he wasn't an ace by any sense of the word, he had been "out there," in aerial combat. His pilots looked up to him with hopes of one day being one of those that had been "out there." And that was General Remington's undoing.

A year prior he was deployed as the commander of a Combined Task Force Operation in Turkey, charged with enforcing the combat air patrol over Northern Iraq. In 1994 two of his F-15 pilots misidentified two U.S. Army UH-60 Black Hawk helicopters as hostile and fired on both, destroying them and killing all 26 military and civilian personnel aboard. A military investigation faulted the pilots, members of a controlling AWACS aircraft, and the failure to adequately integrate Air Force and Army elements. Remington, as the commander, was given an administrative reprimand and his career was pretty much over at that point. I knew he was just the ceremonial scapegoat and wondered what he could have possibly done to prevent the tragedy.

The wing commander’s larger outer office was lined with what had to be the lineage of the 86th Fighter Wing, established a few years after the end of World War II and just a year after the Army Air Force became the United States Air Force. The wing had a storied past, starting with the P-47 Thunderbolt, the F-86 Sabre, the F-101 Voodoo, the F-102 Delta Dagger, the F-4 Phantom II, and finally the F-16 Falcon. Of course the last fighter in that long history departed earlier in the year. His secretary read the name under my wings and got up before I could introduce myself. “He’s expecting you, just walk right in.”

He sat behind his desk, reading what I recognized to be a classic in the Air Force fighter pilot world called, “A Discourse on Winning and Losing.” It was collection of works from retired Colonel John Boyd, an icon in the Air Force fighter pilot world and for those of us with a fondness for aeronautical engineering. The general’s spiral-bound book looked identical to mine, only worn from repeated reading. Colonel Boyd had never been officially published, but his many papers and briefing slides had to be the most read collection in Air Force history. The general looked up and gave me a weary smile. I offered my salute, which he returned.

“Welcome to the 86th Wing,” he said. “Thanks for coming by.” He stood, gently lowered the book to the desk, and shook my hand.

“General, your copy looks even more threadbare than mine.”

“I didn’t know you were a fighter jock,” he said.

“I’m not,” I said. “Colonel Boyd had a degree in economics first and then industrial engineering. I did it the other way around. I am a fan of his energy-maneuverability theories.”

“Me too,” the general said. “John Boyd knocked some sense into the Air Force after Vietnam and made a hell of a lot of enemies in the process.”

“A grenade up the chain of command,” I said.

“You got it,” he said. “You know how many combat kills he has?”

“No, sir.”

“Zero,” he said. “Not a one. Best damned fighter pilot in the history of fighter pilots, not a single kill.”

“His tactics have racked up hundreds of kills,” I said. “That makes him an ace in my eyes.”

“James I think I am going to regret not being around for your command. But those are the cards we have been dealt, so be it. Let me give you my standard talk for new flying squadron commanders.”

“I’d like that,” I said.

“Command is different, you know that. In the official eyes of the military, a commander has invested upon him a special power that no other human being will ever know. But, between you and me, in the Air Force it is different. And that is doubly true for the commander of a flying squadron. So let me ask you, James, what is the difference between command and leadership?”

“A commander has the additional power to order people to their deaths,” I said. “A leader has to convince subordinates the plan of attack is in their best interest. A commander should do that if possible. But even if it isn’t in their best interests, a commander can tell his troops, ‘take that hill.’ And if taking that hill means certain death, so be it.”

“That nails it, James. So a commander also leads. So, final question, what is the most important aspect of leadership?”

“Taking care of one’s people,” I said. “Period.”

“That’s definitely true,” he said. “You have to remember that as a commander. I see from your record you are steeped in operations. Up until now, your career has been focused on flying airplanes, on the pointy end of the spear. But all that changes now. You focus on your people, let the operations officer handle operations.”

“I can do that,” I said.

“This is going to be the most rewarding job you have ever had, or will ever have,” he said, standing. “You are about to learn something that cannot be taught in a classroom, it has to be learned first hand. You have to experience it.”

“I look forward to that,” I said.

General Remington sat back in his chair and stared into my eyes, willing me to blink. I blinked. He smiled and rose, as did I.

“Welcome to the brotherhood of commanders.”

Over the next year I was to meet and work with many of General Remington's former staff and, without exception, they all thought highly of him. He managed to shepherd the wing through a very tumultuous time and, if it weren't for the shootdown, would have be primed for a second star. But he failed to understand what was going on in the trenches. The figher ace wanna bes were blood thirsty for kills, they wanted to shoot something down. Many Monday morning quarterbacks asked why the F-15 pilots were in such a rush to pull their triggers. The helicopters were at low altitude and appeared to be operating without knowing they were at risk. Why not visually sight the foe first? Because if the helicopters had landed, they would no longer be aerial kills. As the charismatic leader, Remington didn't need to get into the trenches with his troops, they were willing to follow him anywhere. But had he been more engaged, perhaps he would have spotted the problem before it became deadly.

What about the "something that cannot be taught in a classroom, it has to be learned first hand" bit? He was right. It took me a few years to figure it out. Read on . . .

2

Directing

C-20A 30500, Matt Birch (http://visualapproachimages.com/)

Lieutenant Colonel Clevis Haney cut his Air Force teeth flying the C-130 and eventually found himself in Germany to take over the 76th Airlift Squadron. His prime motivation was getting himself ready for the airlines and that meant he would fly the Boeing 737 (CT-43) and take most of the flying in that airplane for himself. He devoted almost no time and effort into his actual job, commanding the squadron. Those duties fell to his second in command, the Director of Operations, Lieutenant Colonel Felix Henderson. Needless to say, it didn't go well. After less than a year on the job, Lieutenant Colonel Haney was presented with thirteen inspector general complaints filed by members of his squadron. He was offered the choice between early retirement or legal proceedings that could end up with him thrown out of the Air Force at a reduced rank and a reduced pension. Haney made the right choice. And that's where I came in.

"So you are the new commander," he said, shaking my hand.

"In about a week," I said. "I would appreciate anything you can tell me about the people and the job."

"It's a piece of cake," Haney said. "The squadron runs itself and all you really have to do is fly, sign a few personnel reports, and keep the wing happy."

"How are the people?" I asked.

"The best," he said. "No worries."

"Any trouble makers I need to know about?" I asked.

"Hell yes!" he said. "You got a bunch of cry babies that can't wipe their own noses without permission. They will make your life hell."

"Any names?" I asked.

"No need for that," he said. "Basically all of them."

"How about an example?" I asked. "Just one."

"Nah," he said. There was a knock at his office door and a young captain stood, waiting. "What?" Clevis said. "Can't you tell I'm busy?"

"Sorry, sir," the captain said. "I thought you wanted to know immediately when another flight engineer busted a checkride. Well, Sergeant Wells just busted his checkride."

"Okay," he said. "In another week it won't be my problem anymore." He looked at me. "It will be yours."

The captain left and I looked at Clevis. "Are you having problems keeping crewmembers trained?"

"Yeah," he said. "I think people just aren't as smart as they used to be. We never had these problems when we were their age, did we?"

Clevis wouldn't give me any specifics; before we were done he had reversed his early "It's a piece of cake" statement. I came to the conclusion our meeting had been a waste of time.

The day after I assumed command and visited the squadron's standardization and evaluation office, I found Captain Lenny Seaton updating a grease board with the latest check ride results. As I entered he snapped to attention. "Good morning, sir."

"Guten tag," I said. "Got a few minutes to talk about check rides?"

"Yes, sir." I took the seat facing his desk and Lenny sat, pulling a 3-ring binder from a shelf. He rattled off the latest pilot results without looking at the book but turned to individual tabs to cover the flight engineer, radio operator, and flight attendant results.

"Do you have a trend analysis program?" I asked.

"The wing does that for us," he said. "Every quarter."

"And how are we doing?" I asked.

"We got flagged two quarters ago," he said. "Seems our flight engineer initial and annual qualifications aren't doing so well. We didn't improve one quarter ago and it sounds like the problem is only getting worse."

"Why is that?" I asked.

"Well I don't want to bad mouth the old boss in front of the new boss," he said. "But in my opinion, it's just my opinion, sir, it's because we don't let them fly on our local trainers."

"What? That's crazy," I said. "What happened to train like you fight, fight like you train?"

"That's what we all said when Colonel Haney made the change," he said. "But Haney wouldn't even hear our side of the story, told us to 'shut up and color.'"

That was an insult from days of yore, I knew. Old school commanders would tell their subordinates to "Shut up and color," as if addressing school children. "Why would he do that?" I asked.

"I think he was prepping for the airlines," Lenny said. "Colonel Haney flew the Boeing, and the airlines don't use engineers on their 737s. But that's just my opinion, sir."

As the year unfolded I found several instances where Haney's decisions came down unilaterally and any opposition was immediately squashed. This sort of directing leadership style certainly had its place in the military, especially in combat or other time sensitive situations. But it resulted in a squadron that was afraid to speak up or offer the kind of advice I would be needing to run a squadron flying three types of airplanes all over the world.

3

Political

In the early nineties the Air Force got rid of an organizational structure designed to fight the Soviets strategically and everyone else tactically; so gone were the Strategic Air Command, the Tactical Air Command, and the Military Airlift Command. Those three were replaced by Air Combat Command and Air Mobility Command. The change was long overdue but there were unintended consequences. Before the change, the rules about who could fly a C-20 Gulfstream III or a C-21 Learjet 35 were set in stone. You had to receive type specific training. Commanders in the chain of command could fly these airplanes with familiarization training and an instructor. But that was it. But since these rules were written for the Military Airlift Command, they ceased to exist for a time. And that is the situation as I found it in 1994.

As a squadron commander, my direct boss was the group commander. Colonel Stanley Wozniak was just a year older than me, but he was what we called a "fast burner." He married the daughter of a retired 4-Star and made every promotion in minimum time: 3 years early to major, lieutenant colonel, and colonel. He started his career flying a C-130 and was almost immediately pulled into a promotable staff job. He got his squadron commander tour in trainers and found himself in charge of a group of VIP airlift aircraft, aeromedical aircraft, and combat airlift aircraft. Of those, he was only familiar with the C-130s. He was an immediately likable officer who seem to have a knack for saying the right things and the right times, no matter the situation. After our first meeting I thought he was as perfect a group commander as I had ever met.

"What worries you the most, James?" he asked. "What is it that is going to get us into the most hot water?" It was the perfect question. It was a variation of my chief of safety question for all my safety officers back at Andrews: "What will cause the next accident?"

"We have two general officers flying our Learjets who have never been trained," I said. "Under old Military Airlift Command rules, they couldn't touch the airplane unless they had received a minimum of one week simulator training. These two general have no training whatsoever."

"That's a tough one," he said. "But that was done before you or I showed up here, so I think we are kind of stuck. Not much we can do, don't you think?"

"I suppose," I said. "The old rule book no longer exists. But can't we write a new rule for the future?"

"You do that," he said. "Let's see if we can get that into the regs. You will have my full support. Anything else?"

"I've worked with the new wing commander before," I said. "He is quite political. I can see him giving out Learjet rides to people outside the chain of command."

"Well that is clearly against the regulations," Wozniak said. "We aren't going to let that happen, James."

It was exactly what I wanted to hear and that is pretty much how it worked for about six months.

During my formative years as an Air Force officer I learned to mistrust those with more political skill than other talents. But in Wozniak I learned politics was a skill I needed. The Operations Group often faced problems of one sort or another that could only be fixed from outside our chain of command. Wozniak had a personal relationship with the other group commanders — in fact, with commanders in other military services or countries — he could just pick up the phone and solve the problem. For the first time in my career, I started attending wing parties with a purpose in mind. I wanted to develop my own political network. But I quickly learned there was a limit to what politics could do for me.

"We got a problem," Lieutenant Colonel Felix Henderson said, placing a set of flight orders in front of me. "The wing commander promised the left seat of one our our Learjets to a one-star from higher headquarters. The general has never flown anything other than fighters and trainers."

"I'll take it up with the Colonel Wozniak," I said.

We had two weeks to work the issue, but it was all for naught. "The boss wants to do this," Wozniak said. "He says if you put an instructor pilot in the right seat you have everything you need."

"This puts a very young instructor pilot in a very bad situation," I said. "My most experienced Learjet instructor has just over 2,000 hours total flying time, less than 500 in the Lear. There are a few situations in the Learjet that an untrained pilot can screw up faster than an instructor can correct. This isn't safe."

"We have our orders, James."

The weather for the day of the flight was CAVU, ceiling and visibility unlimited. The one-star was a very good pilot who deferred to the instructor when needed and the flight was uneventful. (The best kind of flight.) In the end I lost a lot of "style points" with the wing commander, but that was a part of the job. In my eyes, however, the group commander fared far worse. While I would often rely on his political skill to get us out of jams, I could never again take him at his word.

4

Authoritarian

I didn't know what to make of Lieutenant Colonel Arthur Johnson at first. In a meeting of equals or superiors he is quiet and unassuming. When given an order his answer is invariably, "yes, sir." When speaking with a fellow squadron commander he usually defers to his peers; but if he has a differing opinion he almost always voices himself almost as if apologizing. But his demeanor to his subordinates was completely different.

Art started as a Second Lieutenant in a C-130 squadron where he gravitated from copilot to aircraft commander to instructor pilot, as was expected of the most competent pilots. He then moved to Little Rock Air Force Base, the C-130 "school house." From there it was to Kadena Air Base in Okinawa and then to Ramstein Air Base, Germany. He stayed long enough to inherit the reins of the squadron.

In any Air Force Base with a flying mission, the flying squadrons are where the rock stars live. And at a base with more than one flying squadron, there is a definite pecking order. A C-130 squadron would be on the bottom of most lists, but at Ramstein, they were the kings. The only two other squadrons were a C-9 aeromedical unit and my squadron, the VIP squadron. The C-130 squadron was a "combat airlift" squadron. Lieutenant Colonel Arthur Johnson was in command of the wing's most important mission.

The new wing commander made the base's transition from fighters to combat airlift complete. The last F-16 "Fighting Falcon" had departed earlier in the year. The last fighter pilot to leave was the wing commander himself, General Remington. Now the new wing commander was a born and raised C-130 pilot. General William "Paul" Paulson surveyed his staff with a smile. "Paul Paulson knows where to place his priorities," he said. "And that is on combat airlift. But that doesn't mean all the other missions aren't important." He spoke at length about the importance of the wing's many missions. "And don't forget your people. Without people, you have nothing."

The staff nodded approvingly. Only I knew it was a lie. I had worked for then Colonel Paulson back at Andrews and knew he viewed people as obstacles on his way to promotion. Of course I kept my views to myself. "You are my commanders," he continued. "It is vitally important that each of you has an intimate knowledge of the inner workings of the overall wing command structure. Get to know your fellow commanders!"

And so it went. His words, if not his intentions, were certainly true. And I had very little knowledge about my combat airlift peers. "Want to get intimate?" I asked Arthur Johnson.

"If we have to," he said. "You busy now? I can give you a tour of the squadron."

"Sounds good."

Art's squadron operated thirteen combat airlift C-130E aircraft, the oldest model still flying in the U.S. Air Force. They were built in 1962 and had seen action in Vietnam and were now delivering supplies to war torn Bosnia. While Art's squadron included over one hundred pilots, navigators, flight engineers, and load masters, it was also supported by a variety of other squadrons all helping to keep the old bird flying. But just barely.

"This is a foreign world to me, Art," I said as we strolled alongside his flight line. "It looks like you have more than a few 'parts birds,' and most of them seem to have their own collection of fluid dripping from the engines and wings."

"We manage to keep 63 percent of them mission capable," he said. "That's the highest MC rate for any E-model unit in the active duty Air Force."

"Active duty?" I asked.

"Yeah," he said. "The guard and reserve do better. But they don't fly as much as we do. We ride these girls pretty hard."

Over the next few weeks they had to ride them even harder. General Paulson volunteered the base to take on more of the combat air delivery load into Bosnia, raising the daily sortie count from three to five. Art's squadron rarely hit that target. "We are short manned in every crew position," he explained at one of our weekly staff meetings. "The people are hacking it, but just barely."

"Well this is important stuff," General Paulson said. "We need 35 sorties a week, you are only giving us 25. We need 35."

"You'll get them, general," Art said.

As we left the meeting I doubled my pace to keep up with Art's lanky six-foot-five frame. "How are you going to do that, Art? I thought you said you were just barely keeping up getting 25 into the air each week."

"I'll find a way."

Of course it was none of my business. Besides, I had my own business to attend to. A week later, Felix Henderson, my second in command, walked into my office just about quitting time, holding two beers. "Maybe you should join the rest of the squadron for beer call," he said.

"Good idea," I said, leaving my paperwork behind. It used to be an Air Force tradition — a squadron beer locker and Friday "beer call" — but it was a dying tradition. I gladly joined my squadron pilots in the happy banter and war story telling.

"Sir, can you prove or disprove a rumor," one of my Learjet pilots asked.

"I'll try," I said.

"The C-130 squadron is going to six-day weeks," she said. "There's talk that the rest of the wing is going to follow. Are we going to give up our weekends too?"

"The combat airlift team is under a lot of stress," I said. "They have an important mission, an old airplane, and serious manning issues. We are in a different situation. Many of us already work on weekends, but we get a lot of weekdays off. I don't see that changing."

Felix Henderson listened as I talked. After the young pilot excused herself, Felix pulled me to one side. "Art Johnson is a tyrant," he said. "I heard he's really cracking the whip over there. He's going to break his people."

"Maybe," I said. "But let's not second guess his decisions in public."

At our end of year meeting most of the staff presented their annual statistics. The Operations Group still had another week of flying and would wait until the next meeting. The first slide to go up came from the security police commander. The base-wide "Driving Under the Influence" rate was up three times over the previous year. "No tolerance," Paulson said from his chair at the head of the table. Next the judge advocate showed the divorce rate among enlisted and lower level officers; the rate had doubled. "Unacceptable!" Paulson said. "This is a sign you aren't taking care of your people!"

But then came the hospital commander with something I hadn't expected. "We've had four suicides this year," she said. "While having a suicide in a wing this large isn't unheard of, four suicides is some kind of record."

While none of the slides singled out any particular squadron, I knew that most of the DUIs were from the C-130 community; one was from my squadron. Most of the divorces were also C-130 people; again one from my squadron. I didn't know about any of the suicides, so I asked. "Yeah," Art said. "They were all from my squadron."

"I'm sorry," I said.

"Yeah," he said.

At the first meeting for the new year the Operations Group presented its annual statistics. Art did get the C-130 weekly mission rate up to 30 for most weeks during the year and actually hit the 35 target once or twice. But in the end, the Air Force took the bulk of the missions away from our base and gave it to deployed C-17s at nearby Rhein-Main Air Base, also in Germany. One C-17 could lift as much as our daily allotment of five C-130s, and do so more quickly and more reliably. It was the right solution that should have been implemented at first. General Paulson's bravado in volunteering for more missions hurt the Air Force's mission in getting relief supplies to Bosnia, but it seemed to me the damage went beyond the mission. Art finished his command tour with high marks. He had never turned down a mission and never refused an order.

5

Participative

I first met Mark Honable when we were both second lieutenants on the snowy mountains of Washington State, battling the elements and the pretend bad guys in Survival, Evasion, Resistance, and Escape school. We were paired together evading mock Russians until we were both thrown into Prisoner of War training. Though he started active duty a month before me, my commissioning date got me promoted into an earlier year group and we ended up almost two years apart in rank. As a navigator he needed to get out of the cockpit to get promoted; he ended up in command of a maintenance squadron charged with keeping the Air Force's oldest C-130s flying.

"Command" is a special rite for an Air Force officer. It not only means you are "in charge" of people, but that you have their lives and careers in your hand. For some, command happens immediately. An Air Force officer in the security career field, for example, can be placed in command of a squadron of guards as a second lieutenant. For pilots and navigators, Uncle Sam demanded ten years in the cockpit first. Major Mark Honable got selected for command very early.

"Squadron Commander Mark Honable," I said as I entered his office. It was larger than my office, befitting his position leading a larger squadron.

"It's just a maintenance squadron," he said. "James it's good to see you after all these years. I never expected to see a troublemaker like you in command of a flying squadron; but you are probably the perfect officer to take over the mess Colonel Haney left behind."

"I'd say you have the bigger challenge, Mark. Those are some pretty tired looking birds out there."

"Yeah, they are," he said. Mark pulled out a binder from a shelf behind his desk. "We have the oldest C-130s on active duty, but we have the best MC rate of any E-model. We are pushing 63 percent." A maintenance capable rate of 63 percent would doom any commercial operation to economic failure and it would certainly doom my squadron to failure. But for a combat airlift unit, it must have been pretty good.

"Can you keep that up with an increased ops tempo?" I asked.

"Well that's the thing," he said. "It was 60 percent when I took over and Colonel Johnson said we need to do better. I sat down with my section chiefs and we brain stormed for a way to do that. We changed our scheduling to go six days on, two days off. That seemed to do it, but everyone knew we could only do that for a short period or people are going to get burned out."

"And now we have a wing commander asking for even more," I said.

"We just got to keep pushing," he said. "It's not like we have a choice."

"How do you motivate the troops to sacrifice like this without a recognizable threat?" I asked.

"I don't know," he said.

"Sometimes you have to tell your boss 'no' for the good of your people and the mission," I said.

"That's easy for you to say," he said. "You're already a lieutenant colonel and if you get tossed out you have the airlines to fall back on. I'm up for promotion next year and if I get tossed out, I don't have a Plan B."

I made a mental note to keep an eye on Mark's squadron and to offer a pep talk now and then. Of course I had my own set of problems and my silent promise went unfilled as the year unfolded. The new wing commander gave Mark an ultimatum: he needed to get his MC rate to 65 percent or face the consequences. Mark got the rate up to a decimal point under his target, but then his people broke. Four of his mechanics were arrested for driving while intoxicated in as many weeks. One of those while driving off base in a German hamlet. Then came two suicides. The wing commander blamed Mark.

Meanwhile I had a major in my squadron competing in the same promotion cycle as Mark, with considerably fewer responsibilities. Major Karl Stück was a failed C-130 pilot who had been kicked out of the cockpit, found himself in a promotable staff job, got promoted to major, and then found himself in my squadron as a Learjet copilot. His prospects for further advancement as a pilot were not good and I could not recommend him for promotion. That generated a meeting with the wing commander.

"No good commander would write such a negative recommendation for one of his officers," General Paulson said. "You need to change it."

"Sir, Major Stück is unfit for promotion," I said. "I think it was a mistake to ever promote him to captain, much less major."

"Well someone before you thought otherwise," he said. "We have three majors competing for lieutenant colonel and I have to name one of those three as my top pick. The other two are not getting my pick so you need to change your recommendation."

"Sir, promoting Stück is a mistake," I said. "I cannot recommend him."

Paulson stared at me for a moment. I had refused his orders before and somehow survived; perhaps this was one time too many. I wrestled with suggesting Honable by name. Perhaps my recommendation on Honable's behalf would doom his chances.

"You are dismissed," he said.

Paulson kept his recommendation secret and in the end Stück was promoted, Honable was not. A squadron commander should experience joy when an officer under his or her command is promoted. I felt remorse. Lieutenant Colonel Karl Stück never did upgrade in the Learjet and found himself in another staff job where his performance, I am told, was uninspired. Major Mark Honable never did get his MC rate up to 65 percent but life improved considerably when Paulson was fired and the new wing commander realized the wing had to put an emphasis on restoring manpower levels. Mark, however, was unable to get promoted on his second try and managed to finish a distinguished career as a major after twenty years. He now manages a Home Depot in Lafayette, Louisiana and is very happy.

I blamed General Paulson for this for several years. He was obviously pushing too hard and circumstances proved that the wing should have been working harder to increase manpower levels before increasing the workload. Paulson was on a war footing but the wing was not. I discovered later that the story was more complicated than that. I knew Mark was a humble person; but I assumed his outward shyness was just toward his peers and his superiors. But his replacement told me that his undoing was his shyness with his subordinates. Mark was unwilling to get into the trenches with his people and find out what their challenges were. Had he done so, they would have felt more inspired to put in that extra effort and he would have been less apt to accept every order without some kind of push back.

6

Delegative

Lt Col Margaret Cairns was chosen to lead the 86th Aeromedical Evacuation Squadron after a few years as a line pilot and then as the operations officer, which is the second in command position. Her tenure as the operations officer was noteworthy in that it was in no way noteworthy. She was unfailingly loyal to her boss and never rocked the boat. She was neither popular or unpopular with her people and the thing noticed the most by her fellow commanders was that she was rarely noticed at all. When I first met her at a staff meeting she reminded me that we had spent three years together in a previous squadron. I didn't remember that.

We both found ourselves in the unfortunate position of working for a wing commander who had gone off the deep end. Brigadier General Paulson believed that the best way to earn distinction for himself and his wing was to prioritize a metric that nobody else really cared about, and to push his people to the breaking point. For General Paulson, there was nothing more important than making sure every airplane took off on time.

I had set the example for what not to do early in General Paulson's tenure as our wing commander. Two weeks after Paulson's "all takeoffs will be on time" edict, a Learjet was scheduled to fly a team of electrical technicians to a remote radar site in Italy. One of the technicians forgot a piece of equipment and needed thirty minutes to retrieve it from the shop. The crew asked for direction. "Wait," I said. "Our job is to help them do their job and if they need the equipment, we should wait." Paulson saw this as a high crime and misdemeanor and dressed me down in front of my fellow commanders at the next staff meeting. Our marching orders were clear.

A month later it would be Margaret's turn under fire.

"How are things?" I asked, as I caught up with her walking across the flight line to our weekly operations group staff meeting.

"Not good, James," she said. "One of my pilots filed a fraud, waste, and abuse complaint."

"There is bound to be some of that," I said. "What's that got to do with you?"

"He says I'm the one responsible," she said. "You know General Paulson goes ballistic whenever we have a late takeoff. Last Tuesday we had only one launch and it was a trainer. We needed to do a copilot-to-aircraft commander upgrade sortie but the copilot overslept. He called in saying he would be an hour late."

"An hour late is not so bad," I said. "It would be worth making a public spectacle of the guy as a lesson to everyone, but training hours are expensive.

"You know we can't do that," she said. "General Paulson would have my ass if my squadron had a late takeoff on a training sortie."

"That's true," I admitted. Margaret's first rule was always to obey an order, her loyalty to the chain of command was unbending.

"So I took the first pilot I could find and sent him with the instructor to fly the sortie. We got our on-time takeoff so the wing is happy."

"So the copilot who missed the flight is complaining?" I asked.

"No," she said. "The pilot I had fly the sortie is. He had a dental check up planned and got a nasty gram from the hospital for the missed appointment.

"Ah, the law of unintended consequences," I said.

"Exactly!" she said.

Things got worse for Margaret. The upgrading copilot failed to upgrade in time and her training section was "dinged" for failing to meet quarterly projections. But, as the year progressed, she never deviated from her modus operandi. The squadron muddled along and she completed her tour without distinction and retired from the Air Force. She is now a copilot flying for a major airline where her biggest concern is the monthly schedule bid and how to best fund her 401K while paying off two mortgages.

7

Philosophical bullying

Major General Samuel Foster was the Commander of the 3rd Air Force, a bureaucratic entity charged with leading all United States Air Force efforts in Europe and parts of Africa. The "numbered air force" concept was made necessary in the days of the Army Air Force because of the breadth and scope of operations during World War II. Though the size of the Air Force no longer justified this additional layer of command, it was a concept the Air Force refused to give up.

My only commander-to-commander relationship with General Foster was fending off his office's request to have my squadron begin combat operations into Bosnia. Several senators and congressmen had visited Sarajevo aboard our wing's combat C-130s. That airplane's noisy and stomach churning descent over the combat zone into the high risk airport induced a common reaction amongst our government representatives: air sickness. I responded to his first request with seven pages of classified information about the surface-to-air missile threat around the Sarajevo airport. That seemed to quell the push for a while.

"The clever combatant imposes his will on the enemy, but does not allow the enemy's will to be imposed on him," General Paulson said. "Do you know who said that, James?"

"No, sir."

"Sun Tzu," he said. "You should read more military history. General Foster quotes Sun Tzu at every meeting. Foster is a deep thinker. And lately he has been thinking about Sarajevo."

"I thought we put that issue to bed," I said. "If anything, the tactical situation has gotten worse."

"We need to take the offensive, James," Paulson said. "Foster says, and I agree, that with the proper initiative we cannot fail."

"Elan vital," I said.

"Yes," he said.

"The problem with 'elan vital,' is that it never works," I said. "The Germans and the French demonstrated that in the first World War. Besides, do we really want to get into a shooting war with unarmed airplanes?"

"I wouldn't bet against General Foster," Paulson said. "He's a pretty smart cookie about these things."

Major General Foster continued to push and I continued to push back. He believed the surface to air missile threat was exaggerated and was proven right. Over the next two years not a single SAM was detected, though our intelligence said they were present. We all knew about the presence of anti aircraft artillery but always addressed the threat of SAMs as more important. We eventually began combat operations into Sarajevo. On at least three occasions, we saw the muzzle flashes on approach and were not hit; but the aircraft immediately following us was. In retrospect, the enemy was unable to adapt to the speed of our Boeing, Gulfstreams, and Learjets. But by the time they tried and failed to get us, they were ready for the next aircraft.

8

Coaching

I remember the first time I saw Major Linda Roslyn in a wing staff meeting. She sat in the back row behind the hospital commander, just off to one side so as to always be within her boss's peripheral vision. She wore the badge of a medical doctor but the caring demeanor of a nurse. I knew also she was competing for promotion against Mark Honable and Karl Stück. I never had to deal with her until the matter of blood came up.

"We got a late takeoff in the works," Felix said. As my second-in-command, Lieutenant Colonel Felix Henderson kept a close eye on the day-to-day operations.

"Details, please," I said.

"They were scheduled to depart for Zagreb five minutes ago," he said. "If they don't make it off the ground in ten minutes they are officially late. And get this, they aren't flying any passengers. They are waiting for a load of blood from the hospital."

"Isn't this a weekly run?" I asked.

"Yeah," he said. "You want them to launch any way?"

"No," I said. "That would be silly."

"Well it's going to be you catching the spears at the next wing staff meeting," he said. "Just remember, this is the third time in two months we've been late because of a late blood shipment. Maybe we should launch just to teach them a lesson."

"Have them wait," I said. "I'll visit the hospital squadron commander. Another spear or two isn't going to hurt."

Of course I got sidetracked and never did visit Major Roslyn before the next meeting. I was in good company for the late takeoff, fortunately. The C-130 squadron missed 4 of 5 on-time takeoffs and the C-9 squadron missed 3 of 7. My squadron had missed 1 of 27. By the time Paulson got done embarrassing the other two flying squadron commanders he was too tired to give me anything more than, "you got to do better too, Colonel Haskel." I got off easy. Once the meeting broke up I made a direct line for Roslyn.

"Linda, we need to talk," I said. "I'm James Albright from the Learjet squadron."

"I know who you are, sir," she said. "We spend a lot of time in the meetings seeing you three get beat up, after all."

"Well I got lucky today," I said. "And so did you."

That got her attention and I explained that had General Paulson asked why we were late, I would have had to point a finger her way because of the blood shipment.

"I don't know how to fix this," she said. Her weary eyes told me she just wanted to get back to hospital to get back to work.

"How about a tour of your squadron?" I asked. "Maybe I can learn something that will help us make it easier for you."

As a medical doctor, Linda divided her time between her staff responsibilities and seeing patients. Everyone was overworked, but she shared the burden equally. Everyone, without exception, thought very highly of her. Looking at her grease pencil scheduling board, I saw she was putting in 60-hour weeks.

"I'm sorry the blood was late," she said. "But I don't have time to think. It's all I can do just to keep up with patients."

"You are doing God's work here," I said. "I won't take much more of your time, but maybe we can come up with something."

"The hospital keeps a staff on call twenty-four-seven," she said as we entered the blood clinic. "But not everyone is qualified to handle blood. It is perishable and the lab here is stretched pretty thin just to keep two shifts going. The first person normally shows up at seven, except on days we have your blood shipment when we bring one person in at six."

"How about if we just schedule the weekly shipment one hour later?" I asked. "If the people on the receiving end are okay with that, we can take the pressure off your schedule and my pilots."

"Can we do that?" she asked.

"With the stroke of a pen," I said.

With the stroke of that pen the late blood shipment problem went away, only to be replaced by a host of other problems. When I got the impression General Paulson would not back her promotion I found out her squadron was suffering more than most from the base-wide epidemic of driving under the influence, divorce rates, and early separations. Most of her people were highly skilled and could easily find employment outside the Air Force. While Linda was the first to get into the trenches with her people and share the load, she was unable to defend her people against the increasing demands of an uncaring bureaucracy. After she was passed over she found life much easier, and profitable, as a civilian.

9

Dispassionate judge

As the commander of the United States Air Forces Europe, USAFE, General Galen Tigh was a combatant commander. He reported directly to the Secretary of Defense. Directly beneath him in the chain of command was the commander of the Third Air Force, Major General Foster. I knew that Foster's push to get my non-combat aircraft into combat operations had to be coming from Tigh. And his push, no doubt, was coming from Congress.

General Tigh was a war hero of sorts, with one air-to-air combat victory in the closing days of Vietnam followed by the path to four general stars followed by most of his contemporaries. He had a mix of command and staff jobs, all carried out with some level of distinction. He had the misfortune of commanding the Air Force War College during the 1990 Gulf War, and missed out on an even higher level of distinction. Most of his experience was spent preparing for war and not actually fighting a war.

For a lieutenant colonel with one command assignment I already had a full indoctrination into the four-star general mystique. I had flown with a number of them and spent many hours in the Pentagon either briefing or sitting in meetings with them, the highest level of military officers. Despite all that, I was surprised to be asked to visit General Tigh in his office.

"I read your report," he said after I entered and saluted. "You write very well, no doubt about that. But I need to hear your points face-to-face, colonel. I digest things better on that level."

"Yes, sir," I said.

"There is a surface to air threat in Sarajevo," he said. "But I don't have to tell you that. I know the risks, but I think those risks are manageable. But you need to consider this isn't the only threat out there. There are bigger threats and we need to be ready for them. How can we hope to face the bigger threats if we can't handle something like this?"

I didn't have an answer, so I didn't offer one. The general sat back, behind his desk, and started to rock in his chair. I waited.

"Tell you what, Colonel," he said. "Why don't we put you on the next C-130 into Sarajevo so you can judge the risk for yourself?

"That would be great, General."

It was only after leaving his office that it hit me that he was suggesting Sarajevo was a training mission for the war to come. But was a training mission worth dying for?

I flew the next week in the jump seat of a combat C-130 into Sarajevo. While crossing the Adriatic Sea the crew tested their anti-missile flares, designed to fool an incoming heat seeking missile. They then yawed the aircraft to purge fuel vents in case a round of anti-aircraft artillery hit them.

"What about the fuel in the tanks?" I asked.

"We have fire suppressant foam in the tanks," the pilot said. "You can fire a round right into the fuel tank and she won't blow."

Our arrival into Sarajevo was very steep, around fifteen degrees in pitch. The navigator showed me the telltale signs of electronic radar scanning headed our way and that her electronic counter measures would fool them into thinking we were someplace else. We landed on the approach end of the runway and the pilot stood on the brakes. Halfway down the runway sat the remains of a Russian built airplane, cut in half by gunfire.

"We can only use this half of the runway," the pilot explained. "The bad guys own the town behind the hill to the south and they have a clear shot of the east end of the runway.

I was escorted to the cargo bay where I saw a team of loadmasters pushing out four pallets of food to an awaiting ground crew. I returned to the cockpit to see the navigator lacing up her flight boots with her left pant leg rolled up. It revealed a large bandage around a swollen calf.

"What happend to you?" I asked.

"We got hit two weeks ago, sir," she said. "The Kevlar around the cockpit stopped the bullet but the impact of the bullet behind the Kevlar broke a blood vessel and my leg swelled up pretty bad."

"And you are flying already?" I asked.

"Oh it isn't so bad," she said. "I just need to take my boot off now and then and massage my feet. I'll be fine."

We made it out okay and I returned to my office and was handed a set of orders to begin combat operations into Sarajevo. My C-130 flight into the war zone served to remind me that none of my aircraft had flares, foam in the tank, Kevlar-lined cockpits, or electronic counter measures.

10

Visionary

Clarence Dumont was a competent politician and managed to park himself in the Senate with the intention of staying there forever. But his state of center-right voters tired of his center-left politics and sent him packing. A newly elected center-left President had no interest in the Department of Defense and rewarded Dumont for his party loyalty with the reins to the United State Military.

I first met Secretary of Defense Clarence Dumont while flying him to a conference in Los Angeles. He visited the cockpit and asked what our concerns were, if we had what we needed to do our jobs, and what we thought about the new President. We gave him our prepared innocuous answers and he nodded his innocuous nod. While at the Pentagon I briefed him twice on aircraft issues and each time he seemed less interested when I finished than when I began.

"It's a rent-a-crowd," Art Johnson said as we entered the base theater. Every officer in the wing was ordered to show up for an address given by Secretary of Defense Dumont. "Did you get a sneak peak into what he is going to talk about?"

"Not a clue," I said. "The pilots said he slept the whole way over."

"I thought Paulson ordered you to personally fly him over," he said.

"He did," I said. "But we ran out of instructor pilots so I had to do the Sarajevo run."

"Oh yeah," he said. "I heard a French C-160 got hit right after you. They say you woke the gunners up and the French paid the price."

"Sounds about right," I said. "I wonder how much good we are doing in Bosnia."

"They gotta eat," Johnson said. "I just flew a load of peas in there."

"I flew the U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations," I said. "I think you did more good than I did."

Secretary Dumont's address had nothing to do with combat operations or any kind of military operations at all. It was all about the metrics of treating people like, well, people. His metrics were health issues, divorce rates, driving under the influence rates, suicides, and what he called the "re ups."

"In today's military people vote with their feet," he said. "If your people aren't signing up for the next hitch, you have a problem that makes all the other problems worse."

At the last wing staff meeting of the year, we got our annual report cards from the rest of the wing staff and how we were doing. Most of these metrics were exactly what Secretary Dumont had talked about. As a wing, the rate of driving under the influence had skyrocketed over the previous year. Divorce rates were up. The hospital reported an increase in mental as well as physical maladies. While suicides were not unheard of, they were not common. But we had had four in one year. We didn't have a "re up" rate, per se, but manpower levels were down across the board. I couldn't help but notice the uptick for each metric started in the summer, right about when we had several changes of command.

"If you don't take care of your people," Paulson yelled, "how are they going to take care of the mission?" Half of the staff nodded in agreement and the other half, like me, just sat silently.

The following week's staff meeting, the first for the new year, had more cheerful news. The wing was flying more missions with fewer people. Oh yes, our "on-time takeoff rate" was greatly improved.

"That's showing them!" Paulson crowed.

"That's showing who?" I asked myself.

11

Transformational

By the time I had taken command of a flying squadron in Germany, I had worked for nine commanders in five other flying squadrons. I thought two were fine role models to aspire to. I think most of my peers were surprised when I was selected at the first opportunity after I was promoted to lieutenant colonel, or at all. I had, rightfully I must admit, earned a reputation for being too willing to speak up. Perhaps I am putting that too mildly.

Some would say it is a rebellious nature. Others would say it was a thirst for confrontation. I always thought it was an inner need to see things done safely and by the book. At the end of it all, I think that last idea is indeed true. But it wasn't until a few years after my command tour did I figure out the problem with my "by the book" dogma.

After our first wing staff meeting of the year we all expected, and received, a small pat of the back from our normally tyrannical wing commander.

"Look at that slide and reflect upon what we have all learned!" General Paulson said while standing at the screen end of the projector. It was the first time he had ever left his seat during one his meetings. His finger traced the time line along the horizontal axis from last July until December. Each flying squadron showed a dramatic improvement in his on-time takeoff metric. "Next slide," he ordered.

"Now look at this!" he said. Again he traced a line showing an improvement in the maintenance capable rate for each squadron. Slide after slide, the operational metrics of the wing had improved. To hammer that point in, he asked for the next slide. That slide showed each of the operational metrics superimposed, and each showing an increase beginning in July. "This is what we have been looking for! It shows what can be done when you put your mind to it!"

There was polite applause and a few handshakes as General Paulson returned to his seat. I flipped back through my notebook for my scribblings during the last meeting. I found my hand drawn charts showing the same upturn in charts, only these were about divorces, DUIs, suicides, and separations from the Air Force. Colonel Wozniak nudged my shoulder. "In my office, after this meeting, James."

I walked into Colonel Wozniak's office as he was leaving. "The boss promised the left seat of a Learjet to Major General Clarkson, he's a British Royal Air Force commander working for the NATO component on base. I told him you would make that happen."

"That's against Air Force regulations," I said. "I can't do that."

"James, it wasn't a request," he said.

"I thought we agreed we wouldn't let this happen," I said. "It isn't safe."

"According to you it isn't safe," Wozniak said. "But who made you the final authority of what is, and what isn't safe? Everyone who knows you will acknowledge you are the smartest officer they have ever met. I certainly know that. But just because you are smart doesn't mean you are right. And, frankly, your self-righteous attitude can be a bit tiring after a while. You have your orders.

I am not, and have never been qualified in the C-21 Learjet. I've flown it once. My second in command, Lieutenant Colonel Felix Henderson, is qualified but not an instructor. I sent Felix along with a captain instructor pilot. The weather was good for the first leg and the general managed to keep the airplane upright and in an airworthy condition throughout. For the return leg the weather had gotten much worse and the general, while still in the left seat, asked the instructor to shoot the instrument approach and land from the right.

"Bad form," Wozniak said after our next meeting. "Everything worked out okay but you telegraphed your distrust by sending a lieutenant colonel to sit in the jump seat. We lost some style points in that one."

"I wanted the captain to know we would support him if he had to take the airplane from an untrained general officer," I said. "It was the only option I had left."

"You need to be more flexible," he said. "I respect your integrity, I really do. But if you don't learn to bend, sooner or later you are going to break."

12

Machiavellian

Brigadier General William Paulson was the first non-fighter pilot commander of the wing at Ramstein after a tumultuous time for the base. Controversy was never far from the Air Base, even in recent memory. In 1988, three aircraft of the Italian Air Force display team, the Frecce Tricolori collided and an aircraft crashed onto the runway and into the spectator area, killing 72 and injuring hundreds. Two years later a C-5 Galaxy crashed after one of its thrust reversers deployed after takeoff, killing all but 4 of the 17 occupants. Fours years after that, two F-15s under the operational command of the Ramstein Air Wing Commander shot down two U.S. Army helicopters in Iraq. A year after that, General Paulson took command.

When Paulson showed up, the wing was ready for a change in mission and a "breaking in" period to get its feet solidly planted. Paulson showed up with one mission in mind: on-time takeoffs. He wasn't willing to wait.

"You, better than anyone else in the wing, should understand this," he said after my squadron chalked up its first late takeoff. "I would think a SAM Fox pilot like you would be all in on this effort."

"I guess the motivation escapes me, sir," I said. "At the 89th we defined an 'on time' takeoff as being ready to go when the passenger is ready. And we had an entirely different criteria for training flights."

"Don't you want to see the wing excel, colonel?"

"Yes, sir," I said. "I just don't understand the reason why on-time takeoffs equates to the wing excelling. My priorities start with keeping the flying safe, supporting my people, and meeting the needs of my passengers. I guess if I was part of the combat airlift squadron those priorities might be different."

"Now you are getting it!" he said. "You just keep your priorities in sync with mine, and we'll get along fine."

I never did get my priorities in sync with General Paulson's but I did start to shift my own. I had noticed that many in the wing had shifted their aims from whatever it was they needed to do, to simply surviving. I started to evaluate every decision on how the fallout from the wing commander's office would hit my squadron. I was starting to think of General Paulson as a Machiavellian leader. Everything was becoming defined by his personal self-interest and all actions had to be evaluated against his words versus his actions. But all of this came to an end when I got a phone call from the Vice Wing Commander. "The boss thinks very highly of you, James," he said. "In fact, he wants you to work for him personally. He is promoting you to his personal assistant."

"This is a promotion?" I asked.

"You bet it is," he said. "Your change of command is next month. What do you want to do first?"

"I'd like to take a few weeks off with the family," I said.

"You do that," he said. "But be ready for a ton of work when you come back, we have a lot of stuff headed your way."

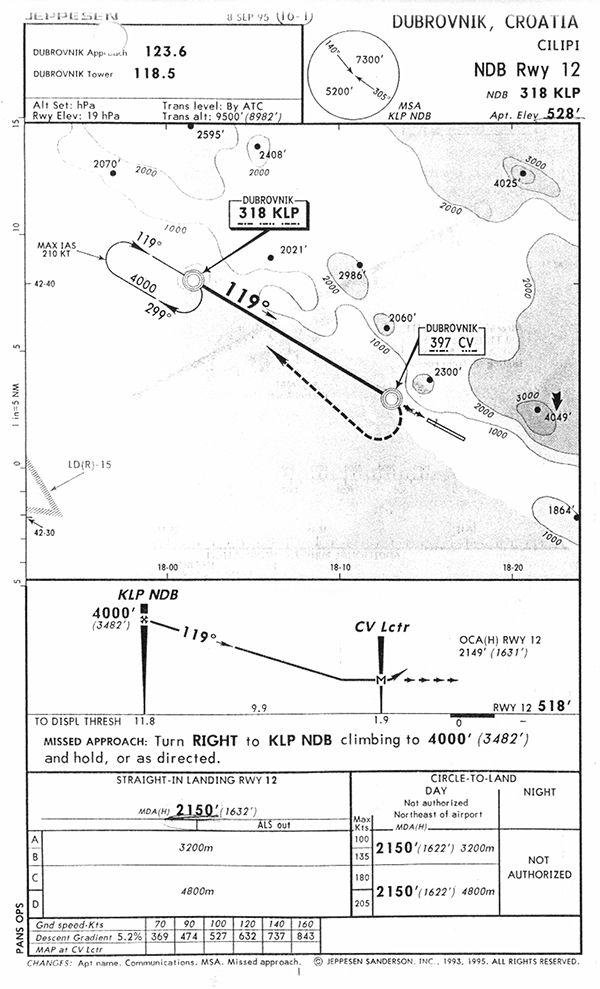

Two weeks after I handed the reins of the squadron to Lieutenant Colonel Felix Henderson, the squadron's CT-43 crashed on the hills north of the Croatian town of Dubrovnik, after flying a poorly designed Non-Directional Beacon, NDB, approach. Everyone on board was killed. The general officer placed in charge of the investigation had no experience in flying NDB approaches, or any kind of approach into a former Soviet satellite country. The investigators kept a tight seal on any findings and refused to invite experts to review their conclusions. Their conclusions, as a result, were wrong.

13

Bureaucratic

Brigadier General Arvil Tudball was selected to lead the Air Force Accident Investigation Board examining the crash of the CT-43, even though he had no experience in aircraft accident investigation, no experience flying a civilian type aircraft like the CT-43 model of the Boeing 737, and no experience flying in an Eastern European country like Croatia. Tudball's talent seemed to be an ability to accept a task and accomplish it within the parameters given him.

I had never heard of Tudball and never met him until the day I was called in to testify. His questions centered on the friction between me, General Paulson, and General Foster. "What does this have to do with the crash?" I asked.

"We'll do the asking," he said. "You do the answering."

The "we" was a board of investigators he had handpicked. But judging by their questions, they knew about as much about flying as he did.

"Sir, take a look at this approach plate," one of the investigators said. "How is it possible for an airplane equipped with only one receiver capable of receiving an NDB signal to fly this approach, when there are two NDBs?"

I studied the approach plate and noticed the distance from the final approach fix to the missed approach point was near the maximum allowed but the minimum descent altitude was lower than surrounding terrain. The plate said "PANS OPS," meaning it was designed in accordance with the International Civil Aviation Organization's "Procedures for Air Navigation Services."

"The minimum descent altitude appears to be too low given the distance of the final approach," I said. "Something is wrong with this."

"What about the two NDBs?" the investigator asked. "How could the CT-43 fly this approach in the first place?"

"That isn't a problem," I said. "Air Force Manual 51-37 allows this provided the final approach course NDB can be tuned prior to any step down fixes. There are no step down fixes so this is okay so long as the switch is made at the final approach fix."

"That will be all, colonel," General Tudball said.

I had no idea where the investigation was headed or why the NDB Approach into Runway 12 at Dubrovnik was a problem. I offered to look into it but was told they had the matter well in hand. Before the results were announced, General Paulson was instructed to talk to me directly. It was the first time we had met in over a month.

"The chief wants me to tell you personally how impressed they are with the way you have conducted yourself," he said.

"The chief of staff of the Air Force?" I asked.

"Of course," he said. "The chief and I have had a long talk about you. The chief wants you to name your next assignment. He wants you to know we support you and we are going to make that happen."

I named my next assignment and two weeks later our bags were packed and we left for Scott Air Force Base in Illinois.

Three months later the accident report was released and the news reported that the blame went three ways. First, the approach procedure was designed in error. The descent altitude was too low, given the length of the final approach. Second, the approach plate had not been validated by the major air command. Third, the crew flew too far north of course.

Of course the first finding validated my initial reaction to the approach plate. The second finding, I also knew immediately, ignored the fact that no major air command ever validated approach plates. It made sense, given the crumbling nature of the former Soviet Empire. The approach into Dubrovnik was once an Instrument Landing System and was perfectly safe. But when the Bosnians fled the city, they took the ILS with them. The Croatians cobbled together a makeshift NDB approach that local pilots knew was poorly designed. But the third finding stung. I knew both pilots and couldn't believe they could have flown ten degrees off course.

The report itself was over 5,000 pages. It took me several weeks to finish it but I discovered a piece of evident that the board ignored. The pilots did not fly ten degrees off course. They were looking at an indication that showed them within airline transport pilot tolerances.

Proving that history has a sense if irony, Brigadier General Tudball was assigned to Scott Air Force Base two years after my arrival. I was working legislative liaison for the four-star general while Tudball ran a command post in charge of tracking tanker and airlift assets. My focus was on long term acquisition for the command and his were on day-to-day operations, we operated in separate spheres. We often made eye contact, but he usually diverted his. It took a year, but I finally had a chance for the confrontation I had long planned for.

"The CT-43 report missed two critical pieces of evidence," I said.

"I don't have time to talk about this, colonel," he said.

"I am wondering why you didn't accept Boeing's offer to help with the investigation," I said. "For that matter, I could have provided expertise on the approach that none of your board members had."

"I am not discussing this with you," he said.

General Tudball's reputation with his staff confirmed what I had suspected. He wasn't interested in facts or outside opinions that differed from his charted course. If the command wanted to head in a particular direction, he wasn't going to allow deviations from course. He was the perfect leader for his command post, where any "out of the box" thinking could be a distraction. The Air Force recognized his talent and placed him where he was needed. Perhaps his talent was called for when investigating a crash with worldwide notoriety.

A year later I retired from the Air Force after twenty years on active duty. I was surprised to see retired General Remington at the ceremony. I had only met him for that one meeting on my first day at Ramstein.

"Congratulations, James," he said. "I've read everything I could about you, the crash, and your career since then. It sounds like you are one of the few who fully grasped the secrets of leadership in today's Air Force. So tell me, what have you learned?"

"I'm not sure my lessons were the same as yours, sir," I said. "But it has all been a learning experience. I learned that every style of leadership has its place, but sometimes a particular style is wrong for a particular situation. And sometimes you don't learn that until after the fact.

"Did that happen to you?" he asked.

"It did," I said. "In most of my flying squadrons the commanders were so busy jumping through hoops to satisfy the commanders above them that those of us below ended up getting squashed. I vowed to never be like that."

"I've heard that about you," he said. "You always reacted by protecting your people first. That's a fine trait."

"Well, I used to think so," I said. "But I spent so much time looking out for my people below me, I failed to look out for the people above me. Whenever I pushed back, General Paulson took that as a personal challenge and pushed back in my direction even harder. Looking back, I think even he realized he was going too far. But he wasn't about to give in because I was personally challenging everything he was doing. I should have found a way to give in now and then. But I didn't."

"So what was the lesson?" he asked.

"Loyalty works both ways," I said. "Most commanders are loyal to their bosses to a fault, forgetting their people. With me it was the other way around, I neglected the need to show loyalty to my bosses. Everyone talks about how dysfunctional that wing was. I own part of the blame."

"You are too hard on yourself, James," he said. "But you have learned the lesson I was hinting at. There is no ideal leadership style. You need to be situational. You can never forget the people who work for you. And, as you discovered, you must also never forget those you work for."

Appendix

Source Notes

Source:

Charismatic

Genghis' Leadership Secret: Control the Message [Man, pg. 19]

The Mongols of the 12th Century believe the supreme power, Khökh Tenger (Blue Heaven) resided atop the highest mountain peaks. Anyone could converse with the Tenger, but they had to make the trek. Young Genghis (before he became Khan), convinced a few followers he had done that. The word spread and soon his reputation spread.

'A good narrative is a great source of soft power.' [Man, pg. 19]

PRO: While one's reputation can make the task of leadership easier — it preps the battlefield for your arrival — in today's information age a reputation can be changed overnight, often without your control.

CON: As a leader, if you over-control the message you can find yourself without needed information that runs contrary to your wishes.

Directing

Source:

Genghis' Leadership Secret: Accept Criticism [Man, pg. 33]

Young Genghis and his brother Khasar had a dispute with their half brother Begter. They ambushed and killed him. His mother's scolding made quite an impression on him and he had the story added to the many told about him as a lesson in life.

Killing his half-brother was a crime. His mother's anger taught him a lesson he never forgot. A different boy might have become bitter and vindictive. Not Genghis. To be able to accept her rebuke, to allow others to tell the story, was the beginning of a journey towards a character always open to advice and criticism — a prime component in the range of traits known as emotional intelligence, crucial to leadership at its best. [Man, pg. 33]

PRO: True leadership requires a bit of introspection and a lot of empathy. A leader who can see things from a subordinate's point of view will be better equipped to convince that subordinate to follow. A leader who can accept criticism as a matter of course will be better able to issue criticism in a constructive way.

CON: A weak leader can become bogged down with worry and doubt if the role of criticism directed his or her way isn't understood. That leader will likely issue criticism in an non-constructive way.

Political

Source:

Genghis' Leadership Secret: Keep Promises [Man, pg. 45]

One of Genghis' earliest leadership lessons occurred when he showed up three days late for a battle and his ally was incensed. He accepted the criticism and vowed to do better.

Integrity is a fundamental attribute of good leadership, for without it the trust of allies and those further down the chain of command vanishes; morale plummets, and concentrated action becomes impossible. [Man, pg. 45]

PRO: Leadership goes both ways, up and down, and being able to deal well with people is what politics is all about.

CON: No honorable person sets out to break a promise to an ally; but many are set to equivocate on the nuances. In a political organization the name of the game is often rationalization; but this game telegraphs the wrong messages to subordinates as well as superiors.

Authoritarian

Source:

Genghis' Leadership Secret: Know Your Own Limitations [Man, pg. 63]

Genghis realized that his people's lack of literacy would pose a limitation on his vision. He hired a non-Mongol to introduce a writing system to write his "Secret History" and Genghis' laws.

Poor leaders hide limitations and lay claim to genius, often with ludicrous results. Great leaders acknowledge inadequacies, and seek to make them good. [Man, pg. 63]

PRO: Many organizations are fond of saying, "The difficult takes time, the impossible takes a little longer." The problem with this mind set is we can break things in trying to pull it off. Sometimes the things we break are people.

CON: A leader overwhelmed by the thought of limitations can be ineffectual and paralysed with fear. Nobody wants to follow such a leader.

Participative

Source:

Genghis' Leadership Secret: Cultivate Humility [Man, pg. 135]

The fact Genghis thought of himself as chosen by Tenger, the Supreme Power, would make it seem unlikely that he had any humility at all. But he did. He openly acknowledged that he didn't understand and would never understand. This realization seemed to impart onto him a sense of humility.

[The highest level] leaders are those dedicated not to the cult of their own personality but to the cause, whatever its nature. Such a leader is an individual who blends extreme personal humility with intense professional will. It's not that [these] leaders have no ego or self-interest. Indeed they are incredibly ambitious — but their ambition is first and foremost for the institution, not themselves. [Man, pg. 135]

PRO: A humble leader understands his or her limitations and is able to empathize with subordinates, peers, and the enemy. Such a leader is unlikely to overreach.

CON: Humility can be a double edged sword. On the one hand, too much humility can limit the ambition needed to lead. On the other, history is filled with example after example of leaders who confused the mission with their personality.

Delegative

Source:

Genghis' Leadership Secret: Make Loyalty the Prime Virtue, and Reward it [Man, pg. 67]

Genghis promised total commitment and expected it in return. He often had soldiers executed for betrayal and he was generous with booty and promotions to followers.

For an ambitious leader, loyalty was like gold: hard to find, easily lost. [Man, pg. 67]

PRO: Leaders seek loyal followers; dependability up and down the chain of command assures unity of action.

CON: Loyalty can be blind and leaders need to be on guard that loyal followers are not withholding needed criticism; just as followers need to be on guard against a leader who is heading in the wrong direction.

Philosophical bullying

Source:

Genghis' Leadership Secret: Philosophize (or at least pretend to [Man, pg. 125]

Genghis' success as leader of the Mongols, it was argued, came from his connection to Blue Heaven, or God. But what was God's intent? In the past, Mongols had consulted Shamans, priests, for all the right answers. But Genghis had gone beyond that and was left to consult with scholars and philosophers; he even became known a philosopher of sorts.

Chinese scholars believed rulers should rely on advice. In the fifth and fourth centuries BC, Plato argued that kings should be 'genuine and adequate philosophers', whereas his pupil Aristotle argued that kings 'should take advice from true philosophers'. Whatever his real beliefs, Genghis apparently saw the advantages of being seen as a thoughtful ruler committed to austerity, selfless service and the welfare of his people. [Man, pg. 125]

PRO: Followers want to believe their leaders think on a higher plane and this can serve as an inspiration to follow.

CON: Leaders who tend to get wrapped up in the theory at the expense of the practice can be seen as out of touch.

Coaching

Source:

Genghis' Leadership Secret: Share Hardship [Man, pg. 125]

Genghis suffered many defeats along the way to victory, at one point down to a mere 2,600 men. But he bore the suffering with his companions and that forged a bond like no other.

Genghis' vision was revolutionary: an end to tribalism, national unity. The nature of revolutionary leadership demands sacrifice. [Man, pg. 125]

PRO: Sharing your people's suffering can inspire them to bear even more burdens and work that much harder to achieve your goals.

CON: Being seen to suffer alongside the troops does not guarantee success. In fact, many historical leaders ended as failures and their sacrifices were in vain.

Dispassionate judge

Source:

Genghis' Leadership Secret: In Peace, Train for War [Man, pg. 86]

In today's military it is common to preach, "Train like you fight; fight like you train." But this wasn't always the case.

Nomadic clans had always practised large-scale hunts - battues - as preparation for war, circling wild animals as if they were foot soldiers. This training gave Mongols an advantage unavailable to urban societies, in which large-scale training for war would have been both expensive and unrealistic. For urban societies, the only true training was war itself. [Man, pg. 86]

PRO: If properly trained to the hardships and sacrifices of war in training, troops become patient of hardships during actual war. They become more obedient under pressure.

CON: Training needs to be moderated to make those sacrifices bearable. The troops need to understand the hardships are worth it in the long run, or they may not stick around in the short run.

Visionary

Source:

Genghis' Leadership Secret: Get a Vision [Man, pg. 42]

When Genghis was 19, his clan was set upon and managed a miraculous escape after three days in hiding. His followers believed he had been protected by Heaven. His people looked to him for about where to pasture, hunt, and camp. But Genghis provided more; he had a vision of tribal unity that would eventually lead to a goal where Mongols could rule a nation, an empire, and the world.

Leaders and leadership theorists talk a good deal about the need for vision. But an inspiring vision is a rare combination of the right circumstances, the right vision and the right person, who must dream it up, communicate it and get followers to believe in it. [Man, pg. 33]