"The Rules" are twenty-six ideas I've collected over the years that seemed relevant enough to life in general that I've written each down with a short story to reinforce each in particular. This is Rule Number Twenty-one.

— James Albright

Updated:

2018-01-13

I grew up with a Japanese mom who spoke a little English and a dad who spent about half his Navy life at sea. He was fluent in Japanese, but preferred everyone speak English when he was around. So mom spoke a little but for the most part, watashi wa nihongo hanashimasu. Her pet name for me was "Sensei," which means teacher. I thought she was bowing to what she perceived as a fine intellect in my young skull. But as it turns out she was warning me about thinking I was smarter than I am. She often warned me in her broken English, "be careful, your tongue can be sharp, dangerous."

I think I was ten when she first said that. I should have pieced it together. But as it was, I didn't fully appreciate the intent of her warning until I was forty. A slow learner, me. Maybe I can speed things along for everyone else . . .

Sometimes thoughts are best unspoken

2002

Speaking up to Stupid, Stupid doesn't want to hear it

I was promoted from second to first lieutenant in the fall of 1981 just as the squadron was doing its annual "rack and stack" of copilots. This ritual was a chance for the squadron commander to look at the records of all 18 copilots, consider seniority in the squadron, flying time, and whatever tangibles he thought important. Lieutenant Colonel Kendal Kong was big on the seniority bit, but he also appreciated copilots who spent at least a day or two each week at the officer's club, and he thought very little of copilots who spent more time flying the T-37 for proficiency and the KC-135A for their eventual elevation to SAC-trained killer.

Of course I was still new. Of the 18 copilots, five were second lieutenants, five were first lieutenants, and the remaining 8 were captains. That's captain in rank, but still copilots. In the Strategic Air Command, the guy in the left seat with the Pilot in Command duties was called an "aircraft commander." The way I saw it, with just fifteen months in the squadron and two-thirds of the copilot pool in front of me, I had a ways to go. Things, it seemed, would change. Twice.

KC-135A 61-0284, March AFB, 11 Nov 1989, (Matt Birch http://visualapproachimages.com/)

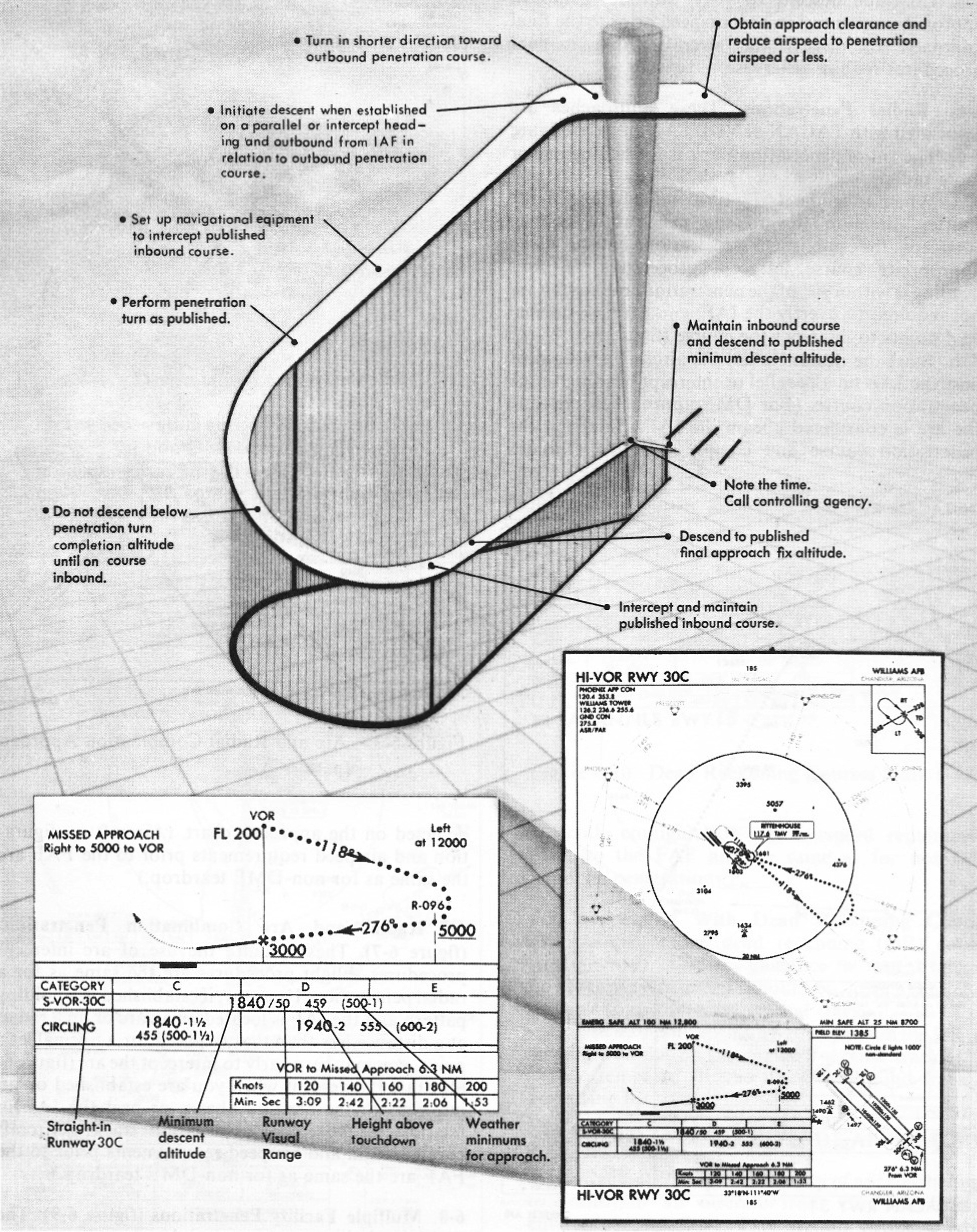

The Air Force, as late as the sixties, was married to the idea that big airplanes returned from high altitude missions using high altitude procedures, called "HI-VOR" or something like that. You basically flew to a point over or near the airport between 10,000 feet and the lower flight levels, threw out the drag, and came on down. The procedure was hard on airplanes and consumed extra gas, but it was a way to do things with minimal air traffic control. In some ways it was easy.

By the time I got to Air Force pilot training, in 1979, low altitude procedures were being taught as an alternate method, but the high altitude procedure was not discouraged. I flew en route descents when the aircraft commander allowed it, but dutifully opted for the high altitude procedure otherwise. "We've always done it that way."

We flew the SAC way. If it wasn't approved by the Strategic Air Command, we weren't doing it. The thing is, however, Mother SAC didn't care if we flew the high altitude procedure or an en route descent, like the civilians. But our old aircraft commanders were trained to use the high altitude "penetration" when going from high to low, so that's what we did. But Jack had another idea.

"That was the most screwed up approach ever," his instructor pilot said while debriefing their trainer. I busied myself with my mission planning, but kept an ear open to Jack's transgressions. I flew with Jack a few times in the T-37, and he seemed like a fine pilot. His hair was too long, his uniform a few days overdue a wash and press, but I thought his instrument skills were good.

"Things were going just fine," he argued back. "I would have been leveled off at the final approach fix altitude just right if you hadn't pulled out the speed brakes. We wouldn't have got the low altitude alert if you had left them alone."

"I pulled the speed brakes to save us," the instructor shot back. "My job is to instruct and your job is to learn. And as a lieutenant, you job requires you to use the word, 'sir.'"

"Maybe the instructor needs to learn from the student," I said quietly. Or so I thought.

"What was that, Albright?" he barked from across the room.

"Sir, I was just talking to myself," I said. "But since you asked, it is up to the pilot to fly a normal en route descent once cleared. The approach controller expects you to do that using a normal descent rate. They expect a 2 or 3,000 foot per minute descent on a penetration, not on an en route descent. We do this in the T-37 all the time and I've done a few in the tanker too. It is perfectly safe. Safer, in fact."

"Well you can kiss your upgrade goodbye, lieutenant," he said. "The boss was going to tee you up for our first lieutenant upgrade to aircraft commander. But it is obvious to me you don't have enough brains to keep your mouth shut, or to fly from the left seat."

I kept my mouth shut and wondered why I had never suspected I was being "teed up" for an early upgrade. My sotto voce defense of my fellow copilot wasn't going to do any good, so why offer it? I gave The Lovely Mrs. the complete replay that night.

"You are disappointed," she said. "You said you didn't care about the upgrade since our plans are to leave the tanker and head to Hawaii before the upgrade commitment was up. But you seem disappointed."

"It would have been nice to been asked," I said. "Being recognized as a lieutenant ready for upgrade to aircraft commander would have been nice."

"It's like you mom always said," The Lovely Mrs. said after a moment of reflection. "That sharp tongue of yours."

"I'll do better," I said.

Public Insubordination, never a good idea

I transferred from the KC-135A tanker squadron before the upgrade would have come up, so no harm no foul for my previous sharp tongue. The new squadron was a dream come true and my upgrade to aircraft commander came quickly. The squadron commander was great and nominated me for the Air Force Flight Safety Officer Course right after two trips where I aborted just prior to hitting the tanker because of a number three engine fire light. Both times our mechanics gave my write up the classic "CND," which meant they Could Not Duplicate the problem. Lieutenant Colonel Swede was fully supportive. "I made the right choice with you, James." But he was being sent back to the Pentagon and we would soon have a new boss. I missed the change of command ceremony because I had a trip leaving that morning, flying the same aircraft on the same mission with the same fire light. I shut the engine down and turned back home to yet another CND. The new boss was not happy with me.

The new boss was Lieutenant Colonel Jerry Spindler, an RC-135 pilot turned staff officer from Air Force headquarters in Korea. His second, the director of operations, was Major William Condit, a pilot from our sister squadron in North Dakota. William came with a good reputation; Colonel Spindler was an unknown quantity. The RC-135 is a similar airplane but with a completely different mission. We flew people from Point A to Point B. The RC-135 is a spy plane that flew along the border of the Soviet Union to eavesdrop with sophisticated electronic equipment. The “R” in RC-135 stood for reconnaissance. The “E” in EC-135 stood for electronic but was a slight of hand used to disguise the real mission. We filed into the squadron briefing room for our first glimpse of the man.

Our squadron could never muster more than four-fifths of its total number, given that one crew was always on the road. But we managed to assemble about a hundred crewmembers that day into our briefing room. At the front stood the new boss. He was a balding and overweight officer with gray, wire brush eyebrows that singled him out as the oldest person in the room. We may have had a radio operator or two with larger guts, but certainly no officer.

“It is an honor to be your commander,” he started. “I think you will find I am a typical crew dog. I get along with everyone and the thing I care about most is the skill and professionalism we each show flying the airplane. “So let’s get on with the business of flying,” he said at last. “I came from RC-135s, planes with real missions. We were on the pointy edge of the gun.” I stifled a laugh at his botched metaphor. “I plan to show each of you how it’s done, the right way. We’ll have no more novice pilots aborting missions flying perfectly good airplanes. You got that Captain Albright?”

“I’m not so sure, sir.” I said.

“In my office,” he said, “now. Squadron dismissed.”

When you are getting yelled at as an airman or young sergeant, the person doing the yelling is given free reign of the airspace and the person being yelled at is in what some call “the brace.” You are to stand at attention, your eyes caged forward, motionless. It was deemed unseemly for an officer, but that’s how I spent the next ten minutes.

“Don’t you have anything to say?” he asked.

“I will follow the rule of law in the flight manual,” I said, “unless presented with compelling evidence that it is unsafe to do so, sir.”

“I think you don’t have the common sense to fly one of my airplanes,” he said. “I’m taking you off your crew. Oh, you think you’re going to safety school? You aren’t. Dismissed.”

Strangely, the only emotion I felt was embarrassment. Having to explain you’ve been fired to everyone you know has to be shaming, even if unjustly.

Fired is fired.

I saluted, did an about face, and opened the door to an empty hallway with a solitary figure poking his head out of the next office. “James,” he said, “come in here.” I followed Major Condit into his office and he closed the door behind us.

“You lay low for a few days,” he said, “I’ll calm the boss down. You kind of shot him in the face in front of the entire squadron on his first day. You can’t blame him for being upset.”

“I see your point, sir,” I said. I had to wonder why I was blind to that very fact with an audience looking on; my intuition had failed me. My mom's words continued to haunt me.

I left his office and found the squadron devoid of all other pilots. The only clue was a note in my mailbox. “Come to the golf course bar, we need to talk.” I showed up and found a few of the squadron pilots had organized a training session and I was the guest speaker.

“We need to know what you know,” Dan Martin said as the others eyed me intently. “What happens if we don’t shut the engine down with a fire light?”

The table was covered with a disposable paper with just the words “Derek!” written upside-down in double ink by our waiter. I pulled out a pen and started to draw. As I covered each facet of the engine fire detection system the concepts solidified and my confidence grew. Each pilot agreed there was no choice in the matter: a fire light equals engine shut down.

The next week my orders to safety school showed up with instructions to visit the colonel in charge of the Pacific Air Forces Headquarters safety office, The colonel said he just wanted to instill in me the importance of what I was doing. It wasn’t an excuse to party for three months, I had to take it seriously.

“I will,” I said.

“And don’t wash out,” he said. “No pilot likes math, but you are just going to have to study hard.”

“I like math,” I said.

“Sure you do,” he said. I left his office and tried to navigate to the parking lot where I ran into newly promoted Major K. Walter Kekumano.

“James,” he said, “your name was in lights up here last week.”

“Me?”

“Yeah.” Walter’s goofy grin forecast more to come. “Your new squadron commander had your safety school orders canceled but didn’t give a reason.

The safety office demanded he replace you with another pilot with an engineering degree and he gave them Bernie.”

“Bernie’s a history major,” I said.

“Yeah,” Walt said. “The staff cut Bernie’s orders but somebody finally figured that out. Now they think Spindler is either an idiot or a liar.”

“I wouldn’t rule out both,” I said.

“Well you be careful, James.” He lowered his voice. “You made him look pretty stupid and he’s going to get even.”

I thought about that for a day or two, thinking of a dozen answers better than “I’m not so sure, sir.” Years ago, in prisoner of war training, I came away from a beating after saying something I thought was funny to a guard who didn’t agree. Some thoughts are best unspoken.

Pointing out the Emperor's Lack of Clothing

Just like a recovering alcoholic, I managed to keep my unwelcome thoughts in check for the most part, falling off the wagon now and then. But whatever luck I had stayed with me through upgrade to instructor and examiner in the Boeing 707, then on to the Boeing 747. I was doing well at the 89th Airlift Wing at Andrews Air Force Base, flying the C-20B, a modified Gulfstream III used for flying members of the President's cabinet and select members of Congress. I upgraded from copilot to aircraft commander in just six months, far short of the 3 year average. So the talk was for an early upgrade to instructor pilot. It would make three aircraft in a row for me. I was looking forward to it.

But, as these things happen, my brain got the better of me. It seemed half the wing was flying by a different set of rules, all for the sake of getting to the red carpet on time. The wing's official motto is "trust one with experience." To that we added, "Safety, Comfort, Reliability." The idea was we kept things safe above comfort, and comfortable above reliable. But our pilots knew the real priority was "Reliability, reliability, reliability." So I modified the official motto as well: "trust one who ignores experience."

The term "Block Time" is given a lot of weight in most Air Force squadrons. It is considered a mark of professionalism when a pilot brings an airplane in from hours of flight and lands within set criteria. In most units, that is usually plus or minus 15 minutes. Most squadrons, but not the 89th. Our wing's official criteria was "Plus five, minus zero." You could be as much as five minutes late, but never early. (You don't want to embarrass the VIP by showing up when there is nobody there to greet him or her.) Of course if the wing said plus five, minus zero, our squadron had to do better: plus one, minus zero.

So, officially, we were expected to land within a minute of an ETA we had declared hours before, no matter the weather, ATC delays, mechanical problems, and so on. Anything later required a written explanation. After a year as an aircraft commander, my record was flawless. But I think a radio operator or two fudged a report or two on my behalf.

I mentioned the mad rush to upgrade, but I had already upgraded from the right seat twice before in my two previous aircraft. Why was it so important? Because, dear reader, of the unique form of torture at the 89th. All copilots are considered less than functional human beings and were not allowed on any flights without an instructor in the other seat. So every flight, even operational trips, included a grade sheet and an opportunity to "bust" a ride and find yourself unqualified. Aircraft commander qualified pilots could fly without instructors and almost always did. But we had to fly a trip with an instructor every few months. And that's when I found myself at VREF minus 15 one day.

"You're slow and getting slower," I said from the right seat.

"I heard you the first time, major," he said. Lieutenant Colonel Tim Shannon was not only an instructor pilot, he was the senior C-20B examiner pilot. I had already passed two of his checkrides, one where he promised to bust me, but couldn't.

Our trip had seven legs, which we traded off. My four block times were within a few seconds of the ETA. So far he barely managed to make two and was well on his way to not making his third. We were five minutes early on final approach back to Andrews. You could normally lose two minutes with taxi technique, but five minutes was next to impossible.

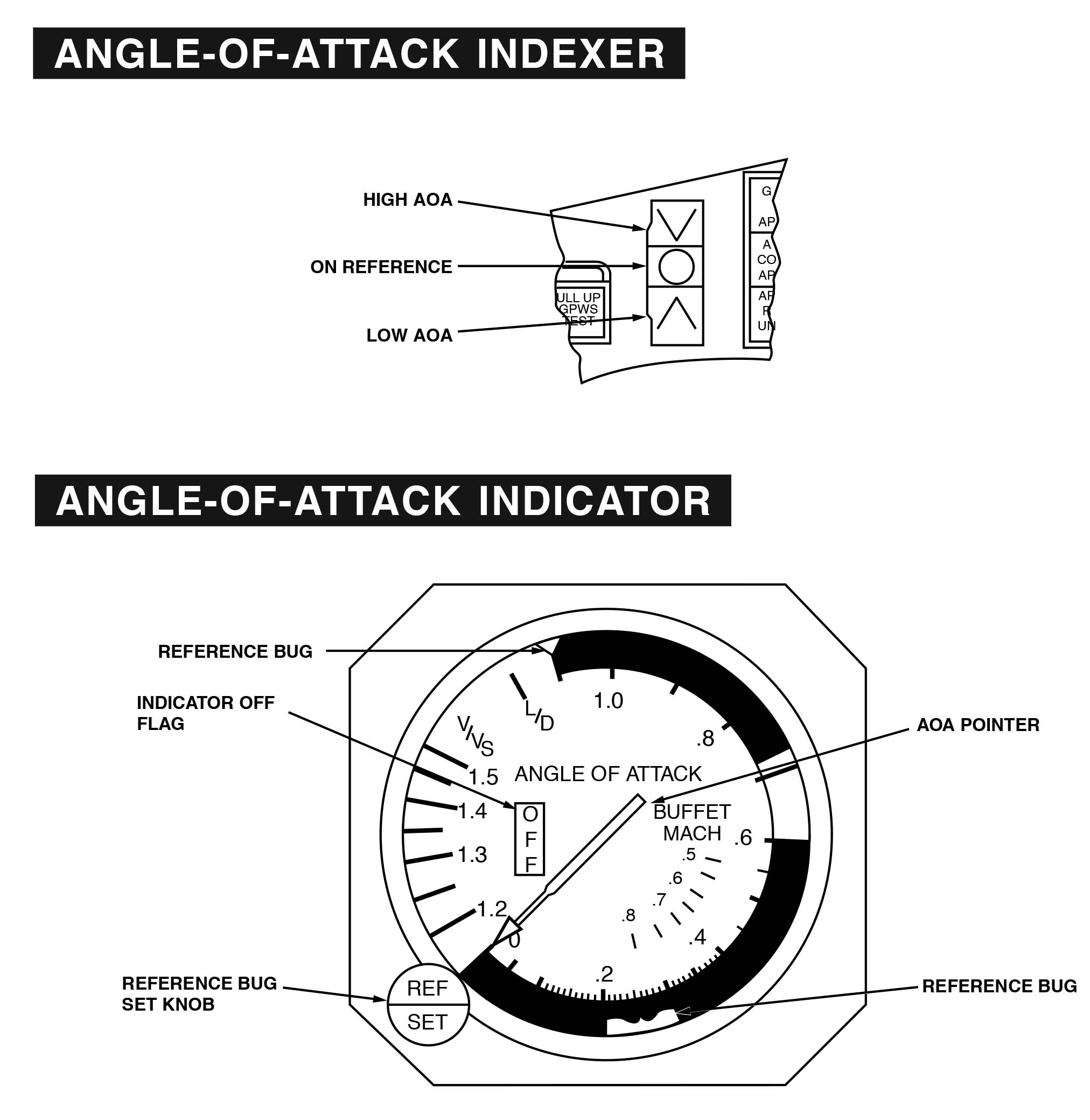

"Isn't that red arrow telling you anything?" I said, pointing to the Angle of Attack Indexer. The top chevron was red and pointed downward, telling the pilot he needs to push the nose down or add a fistful of power. We were dancing around an Angle of Attack of 0.8, stick shaker territory. But we normally flew with the stick shakers turned off, for reasons only the 89th could explain. But the airplane was unhappy. And that made me unhappy.

"I have triple your hours in this bird," he said at last. "I know what she can do and I would have an easier time doing that if you would shut the hell up."

"I'll make it easier for you," I said. "If you don't add fifteen knots right now, I'm taking the airplane."

"You wouldn't dare," he said.

"Try me."

He smoothly added a handful of power and we accelerated to VREF. He landed about five minutes early.

"I'm blaming this block time on you," he said.

"No reverse," I said, "let it roll."

"That will buy us two minutes, tops," he said.

"Pull off the runway and set the parking brake for two minutes," I said. "The passengers will think there is a clearance issue with tower or another airplane. Then taxi slowly."

"You are more dishonest than I gave you credit for," he said. "But I'm still black listing you on the upgrade list."

And all of that happened. We made the block time, I made the black list, and I knew I would never upgrade to instructor pilot at Andrews. But, in a sign that aviation gods look favorably on those wanting to keep things safe, I was promoted to lieutenant colonel and made the wing's chief of safety, a position that allowed me to keep an eye on Shannon and eventually see him mustered out.

"You got lucky again," The Lovely Mrs. said, as she listened to my report of Shannon's exit from the wing. "I don't think your mom would approve. You could have gotten the same thing done without making an enemy like that.

"You are right," I said. (She always is.)

"Some day, James," she continued, "your luck is going to run out."

Luck runs out

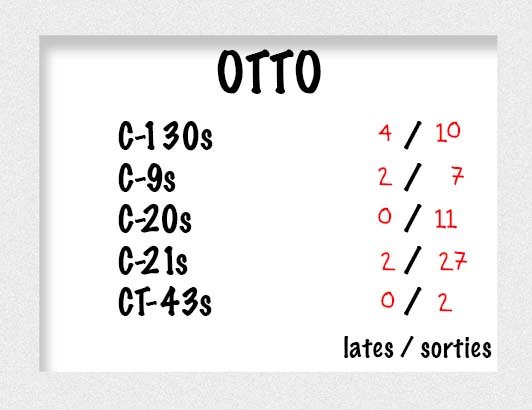

In 1995 I took command of the 76th Airlift Squadron, in Ramstein Air Base, Germany. We flew a Boeing 737 (CT-43), three Gulfstream IIIs (C-20As), and nine Learjet 35s (C-21As). We were one of three flying squadrons trying to survive under the leadership of a madman, the wing commander who had at some point in his career, gone off the rails. He wanted a way for the wing to distinguish itself in a way no other wing could touch, so he invented one. He decided that the wing would push people and equipment to their breaking points, for the sake of having the lowest number of late takeoffs. (If nobody else tracked it, we would naturally have the best record.) The on time take off metric was our most important yardstick, in a wing involved with delivering cargo into a war zone (Bosnia), flying a fleet of aeromedical aircraft (C-9A), and a very high operations tempo on 13 VIP birds. But none of that mattered, because OTTO trumped all.

Our weekly wing staff meetings took place on Wednesday in a big conference room. The table itself was occupied by the general himself, and his seven group commanders. Behind each group commander sat the subordinate squadron commanders. As members of the operations group, we sat closest to the wing commander and all eyes would be on us as the meeting's final slide appeared.

General Paulson started with the C-130 and picked a delay from Thursday, a case where the daily air land mission was delayed by three hours because the aircraft’s flaps wouldn’t extend after engine start. I knew from our earlier ops group meeting the spare aircraft came in late the night before with shrapnel damage to its rudder after receiving small arms fire in Sarajevo. It was the perfect excuse, if there ever was one.

“No excuses sir,” the C-130 squadron commander said when asked. “The spare was broken too but we should have gotten both aircraft mission capable overnight in time for the launch. We’ll fix that.”

“Good,” Paulson said. “All these solutions are within our grasp. We just need to grasp them!” He clenched both hands for emphasis and there were nods around the table. He also picked a delay from Thursday for the C-9 example. I glanced over to the C-9 squadron commander’s notepad and saw both delays listed. The first line read, “pilot overslept.” The second said, “flight nurse overslept.”

“No excuses sir,” she said. “We’ve identified a weak link in our scheduling system and will assign a person to verify the schedule with every crewmember the night before every flight, even the trainers.”

“That’s a start,” Paulson said. “All it takes is for one bad actor to forget to set his alarm clock and the battle is lost. If it happens once, shame on the crewmember. If it happens twice, shame on us for letting it happen.”

“Yes sir,” she said. I could feel her trembling as she spoke.

“Now, on to Colonel Albright,” he said. “Last Thursday C-21 oh, oh, nine six was more than an hour late. Can you explain why the pilots delayed takeoff for more than an hour?”

“They thought it wise to not takeoff without their passengers,” I said. The room erupted in laughter. Paulson’s expression remained blank for about a second and then he too joined in with the laughter.

“Fair point,” he said. He looked over to the Mission Support Group commander.

“Heidi, let’s get the word out to all our users that if the passengers aren’t on time, they aren’t going.”

“Can do, sir,” the colonel said.

General Paulson rose without a word and everyone stood at attention. As he left he looked at the Operations Group Commander and said, “come with me.” As the rest of the staff left, many gave me a look that told me they wanted to cast eyes on me one last time, the squadron commander that would soon be gone.

There were many more OTTO episodes, most of which treated the other squadrons far worse than mine. As my squadron began combat operations we also learned to massage our OTTO efforts to deflect the wing commander's ire. But there is no doubt my sharp tongue, even its humor mode, had cost me. A flying squadron commander normally serves between one and two years, unless fired. I was allowed to see my own change of command after a year, the minimum time.

Lesson Finally Learned

I followed my command tour with a very nice staff job with a promotion promised at the end. I was to return to the Pentagon as a full colonel working in aircraft acquisition. It would be a return to working 12 hours a day in the five-sided puzzle palace while my kids began elementary school. The decision was easy. We found our way to Houston, Texas and began lives as civilians again. I started this chapter flying Challenger 604s for Compaq Computer, in the year 2000.

My kids had never known a life without moving every few years, their dad away from home half the year, and knowing the world extended beyond just their neighborhood. A typical day of homework usually meant me handling math and science, and The Lovely Mrs. handling everything else. There were exceptions.

"Dad, what is the national currency of Sweden?" The Little Princess asked.

"The kroner," I said.

"Do you have any I can borrow for my report," she asked.

"Sure," I said, reaching into the compartment of my briefcase reserved for such things.

A week later she returned the money and showed me the "A" she got on her report. "Thanks, dad."

"Doesn't it strike you as odd," I asked, "that I knew the currency of Sweden off the top of my head and happened to have some in my briefcase?"

"No, of course not," she said. "You are a pilot."

Her next report was about the space shuttle. Most of her peers were doing reports based on newspaper clippings and whatever they could find on the Internet. Not her.

"Dad, do you know any space shuttle astronauts I can meet?"

"Two," I said. "But they are both very busy. I think one is going up on the next launch and the other on the one after that. I think I can get you a tour of the facility."

"That would be great," she said. "But can you call the astronauts, just in case?"

One of my classmates from the Air Force ROTC program had been in space a few times, but the next launch would be his first time as the shuttle commander. I wasn't going to call him. Another flew RF-4s with another classmate, but he had just been promoted to the chief of the astronauts office. So he was out. Next up was another acquaintance who was flying the NASA T-38s. Terry was only too happy to oblige.

NASA T-38s with a view of Space Shuttles Atlantis (foreground) and Endeavor (in the distance), April 2009 (NASA Photo)

Terry got out of the Air Force after 20 years and flew as an instructor pilot on NASA T-38s to give shuttle pilots proficiency time, and the other astronauts some flight experience. He met us at Ellington Field, on the south side of Houston, and we naturally first visited one of his T-38s.

"You used to fly this?" The Little Princess asked. "Right, dad?"

"Sure," I said. "But it was a much older model. Terry was a fighter pilot and probably has more hours in this airplane than I have hours."

Next up was the Super Guppy, a massive airplane designed to carry any cargo the space shuttle could carry. Terry spent most of his time between the T-38 and the Super Guppy, but seemed especially eager to show us the "STA," the Shuttle Trainer Aircraft.

"You flew Gulfstreams in the Air Force, right?" he asked.

"The GIII," I said. "I think it is basically the same aircraft but I've heard you have some special mods on this one."

"We sure do," he said. We walked over to the aircraft and I recognized the tale tell differences between a GII and GIII plus a few more. We walked up the stairs and Terry gestured me into the left seat as he took the right. The Lovely Mrs. and The Little Princess shared the jumpseat.

"That's just hardware store plywood obscuring your windscreen and covering your side of the cockpit," Terry said. "The only thing that works over there is the attitude indicator, which comes right out of the shuttle. That little patch of window you have is exactly the same size as on the shuttle. Everything on the right side of the cockpit comes right out of a Gulfstream II."

"With a few exceptions," I said, tapping my hands on the throttles and landing gear handle.

"Yes, that's right," Terry said.

NASA GII N944NA Space Shuttle Trainer, Ellington Field, 17 Jan 1995, (Matt Birch http://visualapproachimages.com/)

Terry went on to explain the normal training profile was to take the airplane up to between 30,000 and 40,000 feet where he would pull the throttles to idle. He would then extend the landing gear handle halfway to extend only the main gear and then pull the thrust reversers to their interlocks and hit a switch on the throttle quadrant to give control of the reversers to a computer so as to mimic the glide path of a space shuttle. "So other than the reversers, it's just like your Gulfstream," he said.

"I guess so," I said. "Your experience is more recent than mine, and I wouldn't be surprised if you have more hours in Gulfstreams than I do."

"No I just started flying this thing a few months ago," he said. Terry continued what appeared to be a canned briefing and gave the ladies a glance now and then to make sure they hadn't lost interest.

"So this is what the space shuttle cockpit looks like?" The Little Princess asked, pen and notebook in hand.

"No not really," he said. Turning to me, he asked, "James, you know Steve personally, right?"

"I do," I said. "But it has been some time since we last saw each other."

"Why don't you continue the tour and I'll go make a phone call," he said. The Lovely Mrs. took his place in the right seat.

"Is your tongue bleeding, James?" She asked.

"No," I answered. "Why?"

"You were biting your tongue a lot," she said.

"Terry got a lot of the systems wrong," I said. "But this is his airplane, not mine. Besides, he's new to it."

"But you didn't know that until the last minute," she said. "I guess you really have learned that rule about unspoken thoughts. I think you will see just how wise your mom is."

Our quiet discussion was interrupted by several of The Little Princess's questions and then finally with Terry's return.

"Good news, Albrights," he said. "The chief of the astronauts office himself is going to give you a tour of the space shuttle!"

And we spent the rest of the morning crawling all over the space shuttle. I got reacquainted with a friend, The Little Princess aced another report, and The Lovely Mrs. decided her old dog husband could learn new tricks after all.

Over the years since, leaving those thoughts unspoken is no longer a tongue biting exercise. More than that, I've finally realized how it all fits into my mom's first tenet of how to be a good human being: humility first. Just because you have a thought, doesn't mean that thought is correct. You can learn more by keeping quiet. "Always humble," my mom would say. I am learning.