After forty years of flying high performance jets, I am tempted to look back at all the engine failures, cabin fires, and other times where I had to dive into the emergency procedures section of my manuals. I wonder what matter of luck was issued to me when I first ventured into the skies back in 1976. If I had known the excitement to come, would I have still elected to make this my profession? Probably.

— James Albright

Updated:

2020-02-01

A more important question for those of us who manage to survive this kind of excitement is what magic was performed by our instructors that so ably prepared us to recall just what we needed to know at precisely the time we needed to know it?

I believe the best way to learn is from a well told story from someone who has been there before. Over the years I’ve noticed the best story tellers have become my mentors and their valuable lessons have stayed with me without fail. I got a checkride from a seasoned veteran from the major airline world and he gave us a few of his thoughts about dealing with abnormal situations in flight. His three fundamentals for when things go wrong brilliantly summed up my observations on the matter all these years:

3 — Do things for a reason (No reason = no action)

It would be very easy to listen to these fundamental rules, say "yeah, that makes sense," and move on. But then they will not have had the necessary impact. If you want to really benefit, you need to appreciate the human aspect of them and to do that, you need to attach a personal story to them. This can be your story, a buddy's story, or that of someone you respect and feel like you know. In other words, I would like you to attach each fundamental to a mentor.

Your mentor can be an instructor, like the instructor who told me about the first thing I need to do when it hits the fan and when to do that. Your mentor can be your boss, like my squadron commander at Andrews who told me the minute I think I know it all, that I am wrong about at least that. Your boss can even be a peer, like a fellow pilot in our 747 squadron who told me what to do at the end of every emergency procedures checklist.

Your mentor can even be someone you’ve never met; someone you’ve seen in a video or read in a book. The key is that mentor tells a story that has an emotional impact with you. You might wonder about the "Do things for a reason" fundamental and argue that not every reason is published in a manual. That's true. My last example comes from a mentor I've only met on the phone. He sent me his book and it provides a brilliant example of an unpublished reason that has the necessary emotional impact to be a flight lesson I will never forget. He reminded that the best way to instruct, is:

1

Don't get busy

That fighter pilot mystique

I was in the Air Force's Undergraduate Pilot Training (UPT) program in 1979 at Williams Air Force Base, one of five UPT bases. Our base produced more fighter pilots than any other, including those from the Navy. The stated objective of every commander on base was just that, to turn each of us 23-year old kids into fire breathing killers. We started the program in what we thought was a docile primary jet trainer, the Cessna T-37. If we passed that unscathed, we would graduate to the much sexier Northrop T-38.

As it turns out the T-37 wasn't so docile. Between its introduction in 1956 and 1979, the year I flew it, we had lost 111 of them, killing 23 pilots. The T-38 came out four years later but had a higher loss rate, 132 aircraft and 51 pilots. With these kinds of losses, it was easy to get into a hyperactive mindset: I need to do something! And I need to do it now! It seemed most of our fighter pilot instructors were fairly high strung. Even the instructors who had never flown fighters, but wanted to, tended to have their after burners continuously lit.

I mentioned that the T-38 was a marvelous, supersonic rocket. It was also the airplane of choice for the United States Air Force Thunderbird the same year I flew it.

If you ever attended one of those air shows you might have heard the airplane had a roll rate of 720 degrees per second. In other words, you could do two aileron rolls in a second. The procedure for an aileron roll in most airplanes requires you raise the nose a few degrees first. But in the T-38 you just moved the stick left or right and it was over before you knew it. It was quite the machine.

An Instructor Mentor

During my year in the jet we were told half the fleet had an aileron actuator pin installed upside-down and if it came lose it would turn the airplane into a corkscrew. (These days the fleet would be grounded and every aircraft inspected. Back then, you soldiered on.) Then we almost lost an airplane because an electronic yaw damper commanded full rudder and that turned the airplane into a . . . corkscrew. The aileron pin would theoretically happen so fast that if you didn't immediately eject, you wouldn't be able to. The yaw damper gave you about a second to turn it off, but if you didn't, the airplane would spin so fast you wouldn't get the chance. A pilot training classmate of mine was flying a cross-country flight with his instructor in the back seat when they both felt the airplane roll suddenly. They both said it at the same time: “Aileron pin!” We were just briefed about the aileron pin problem a few days earlier. They were flying over a remote area of Utah and let ATC know they would be doing a controlled bail out, both pilots ejected and made it to the ground without injury.

The student had to brief our class on what had happened. I asked him, “when did you realize you made a mistake?” He said that after he checked his parachute canopy above him, he shifted his eyes down and caught a view of his empty T-38, flying perfectly wings level in what appeared to be level flight. As it turns out it was in a slight dive and it impacted the desert below, still wings level. So what happened? We think that as he was flying the instructor hit the stick in one direction and he immediately corrected in the other. They were fighting each other but since the cockpits are tandem, neither saw that the other was on the stick. The lesson learned, we were told, was to always know who has control of the jet. But I took away another lesson.

Look at the airplane, the two cockpits, and the wings. Both pilots have a clear view of both ailerons. A simple look left or right would have ruled out the idea that they had an aileron pin issue since one aileron would have been up and the other would have been down. With a bad pin one aileron would have been down and the other normal. Both canopies have mirrors above and both pilots have a clear view of the rudder, and that would have ruled out the yaw damper issue.

In the case of my pilot training classmate, this criticism is a bit harsh. Like me, at the time, he probably had around 150 hours total flying time. His instructor probably had fewer than 500.

I actually knew the instructor pilot better than the student, since I had flown with the IP many times but never the student. The IP was one of those hyper pilots. He was a talker in the back seat. He was always doing something. The next day, I overheard a more senior instructor pilot talk to him in a back room and he wasn't being kind. The younger instructor walked out, red-faced. The senior instructor walked out and spotted me, ask if I overheard the conversation. "Yes, sir," I said. He looked at me and said, "Two part question. First, what's the first thing you have to do in the event all hell breaks loose and you don't have a clue what's going on? Second, when do you do that?" I thought but didn't say anything, so he provided his own answer. "The first thing you have to do is nothing! And you should do that immediately!"

But is that really true? Aren't there moments where doing nothing is the worst thing you can do? An engine failure, fire, control problem on takeoff before V1? Yeah, that requires immediate action. A control problem after touchdown? Yup. A rapid depressurization at high altitude? Yes. A rapid uncommanded flight control hardover? Probably. A cabin fire? Yes. Anything else? I guess it depends on the airplane. But for the most part, if you want to survive, don’t get busy.

So how do you learn to remain calm under stressful situations, and know when immediate action is the only option or when you need to slow things down and think things through? It has been my experience that the need for immediate action is rare.

How about simulators? They are certainly better than they used to be and they give us a chance to practice things that are just too dangerous in real airplanes. But let me ask you this: how many fatalities – ballpark figure – have there been in simulators over the years? I contend that if you know there is no risk to you not walking away from the simulator, the stress levels are artificial. You don’t really know how you will react when it happens for real.

There is a generational problem here too. Pilots in my generation grew up flying airplanes that had engines that quit, fuel tanks that leaked, and flight controls that would do things on their own for no apparent reason. I was once at one of these safety conferences where the speaker said, “We spend so much time training for an engine to quit at V1 but it never happens.” I saw him afterwards and told him it has happened to me three times and that after the first time it gets easier.

That being said, I do think simulator practice is invaluable. You just have to train your brain to go into a script when things go south on you. If an engine fails, have the procedures down so well that there is no chance for panic.

An example . . .

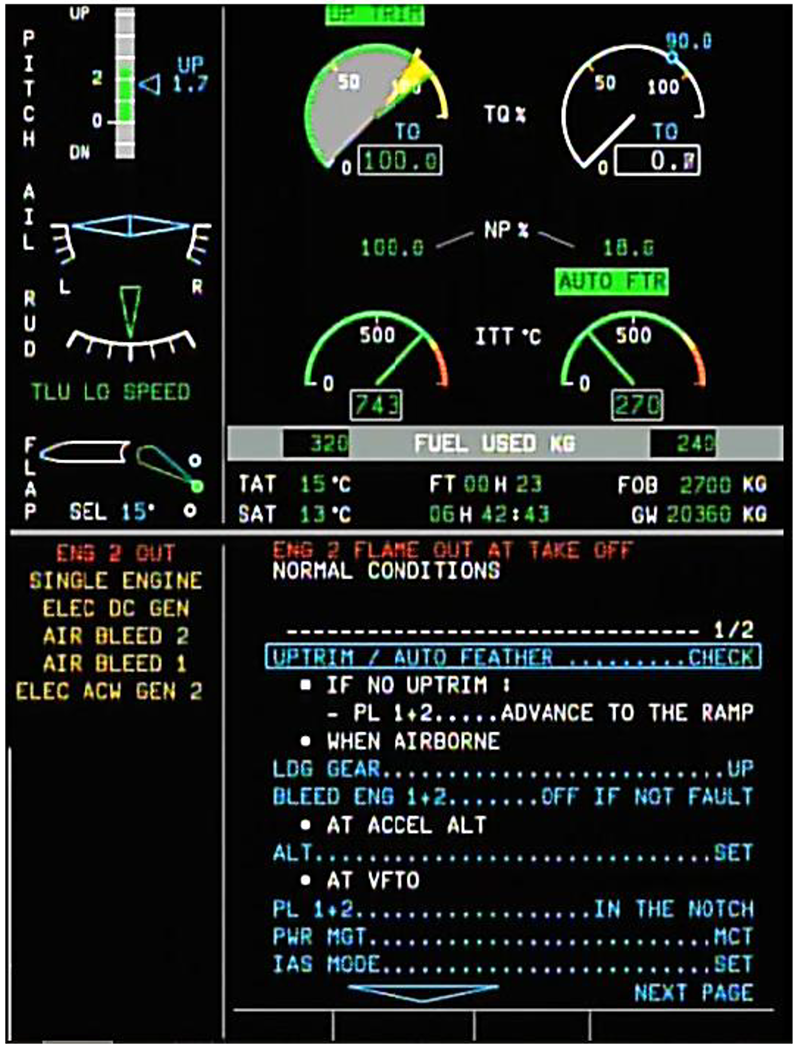

On February 4th, 2015, the world’s confidence in passenger carrying aircraft was shaken thanks to what should have been an easily handled engine failure. TransAsia Flight 235, a ATR 72, had departed Taipei Songshan Airport (RCSS), when the right engine automatically feathered as the airplane climbed through 1,200 feet. The left engine automatically increased its power, a cockpit indication announced the fact the right engine had flamed out, and the autopilot applied the necessary yaw corrections. There were no indications of fire and no real reason to do anything other than fly the aircraft, but the captain disconnected the autopilot and announced “I will pull back engine one throttle.” The first officer said “wait a minute cross check,” but it was too late because the captain had already pulled it back. The first officer then busied himself with the procedures needed to shut down the wrong engine as the captain busied himself by ignoring the need to keep the airplane in coordinated flight. The stick shaker went off just as they completed the number one engine feather.

As the airplane banked to the right the pilots attempted and failed to engage the autopilot. Fifteen seconds later the first officer realized both engines were shut down, five seconds later the captain directed “restart the engine”, eleven seconds later the number one engine began to show signs of life just as the airplane started a bank to the left, the aircraft stalled again, and ten seconds later the airplane’s left wing collided with a taxi driving on an overpass. Moments later the airplane plunged into a nearby river inverted.

It would be tempting to classify this as a simple wrong engine shutdown but that would be generous to the pilots. The aircraft was doing a fine job of handling the situation and even presented the pilots with the proper checklist below the engine instruments. Yes, the captain failed to identify which engine had auto-feathered and immediately pulled back the operating engine. The first officer could have saved the day by being more assertive but succumbed to the desire to “do something, anything” and the captain’s rushed decision gave him “anything” to do. Both pilots were presented with a stressful situation and I think panic led them to the need to do something. In short, both pilots wanted to get busy. That is a natural human inclination, but there are many such inclinations we pilots must train ourselves to resist.

Sooner or later things don’t go as planned in the cockpit, things break, or the system breaks down and we learn the wisdom behind the old saying: “The first step in any emergency is to do nothing. And you should do that immediately.” If you want to survive as a pilot, don’t get busy.

Mentor / Mentee

We lost four airplanes my year in Air Force pilot training and I think most of us became fairly pragmatic about it. That senior instructor pilot's words had a greater impact on me than he will ever know. When it hits the fan, if there are specified immediate actions, do them. But if not, I find it helpful to immediately do nothing, gather all available information, think of procedures and techniques to deal with it. and only then take action. I've had several opportunities to do this with an audience, the crew. Once the airplane is put to bed, have a thorough debrief and you may find you've become a mentor to another generation of crewmembers.

2

Don't get smart

"The best of the best!"

After a while most pilots realize it pays to avoid getting busy and will probably have gained a lot of wisdom along the way. By simply surviving to this point, these pilots can’t be blamed for feeling that they are smarter than the average aviator. If this sounds like a recipe for complacency, it is.

In a previous lifetime I was a pilot for the 89th Airlift Wing at Andrews Air Force Base. You may have heard members of the wing call themselves SAM Fox. SAM is short for Special Air Missions and many years ago they appended their call signs with a slash Foxtrot, to denote a special air mission foreign. Over the years the emphasis was placed on special and 89th pilots tended to think of themselves as a cut above all others. Remember the scene from the movie "Men in Black," where an interview candidate expressed the desire to be "the best of the best, sir!" We had a lot of those types at Andrews. That, of course, is a problem. We Air Force pilots are issued specially reinforced egos and when you add to that ego you are asking for trouble.

I was once flying one of those foreign missions from Washington, D.C. to various parts of Africa with a U.S. ambassador on board. I was paired with an examiner who would trade legs with me and evaluate everything I did. He flew the first leg into Lajes Field, Azores. This was a Gulfstream III and we were just there for fuel. As we came within VHF range I found out we had a 40-knot crosswind. The maximum demonstrated value was only 21-knots but the Air Force established a limit of 30-knots. I knew we had enough gas to continue on to Portugal. The examiner, let’s call him Karl because that was his name, saw me pull out the charts for Lisbon and told me to put them away. I asked him about the 30 knot limit and he reminded me that we were Sam Fox pilots and the limits didn’t apply to us.

Most of the trip through Africa went well and our last night before returning to the United States was Madrid. It was my leg and we were at 45,000 feet crossing the Mediterranean when I noticed the outside air temperature was minus 75. Later Gulfstreams would allow this, depending on your speed, but the limit on the GIII was minus 70. I asked Karl to request a lower altitude and he simply said, “we’re not doing that.” I said, “what about the limitation?” He said, “it’s waived.” I said “By who?” And he said, “By me.”

At top of descent the ambassador himself asked Karl if it would be okay for Mrs. Ambassador to have the jumpseat for landing, and Karl said that would be fine. We were at around 8,000 feet when I asked for the first notch of flaps. Karl moved the flap handle and nothing happened. One of the other things about being a Sam Fox pilot back then is we had the emergency procedure checklists memorized. Yes, we did. We practiced them a lot and I had done several no flap landings without reference to the checklist. I could see Karl attempt to actuate the emergency flap system without success. He moved his airspeed bug to the zero flaps setting and said, “your VREF is posted.”

So there I was flying a no flap approach on a White House mission with Mrs. Ambassador in the jump seat. We had accomplished the flap failure and zero flap landing checklists from memory and as I pulled the throttles to idle the smug voice in my head was saying, “Well done, Mister S. Fox, well done.” As the wheels kissed the runways and I brought the reversers out all hell broke loose. We got a reverser unlock warning horn, a flaps up whistle, and a few other noises I had never heard before. Karl reach cross-cockpit to pull several circuit breakers and then back to his seat to move a few switches and by the time we were at taxi speed things were quiet again.

A boss mentor

When we got back to Andrews I was told that I had done very well and had been selected for an early upgrade. The squadron commander sat down with me and asked about the trip and I told him about all our mistakes. He laughed and said he suspected as much but the SAM examiner and instructor force was very tight lipped about such things. As these things usually happen, our squadron commander was our most experienced pilot, he probably had fifteen years of flight experience and I bet he had five thousand hours of flying time. He told me that in his experience, if you think you know it all, there is at least one thing you are wrong about.

I hear the good folks at the 89th are better these days and guys like Karl, and me for that matter, have been purged from the system. While I was there the wing bragged about a flawless safety record that stretched back to 1960. They had a reverser run away from them when landing in Japan and the airplane departed the runway. That somehow didn’t count. Over the years the list of things that didn’t count started to pile up and I don’t think they talk about a flawless safety record any more. It has been my experience that pilots who think limitations apply to everyone except themselves are too smart to be flying airplanes and we would all be better off if they found something else to do.

An example . . .

So it appears that Air Force pilots belonging to “select” or “special” units are at higher risk for being too smart to be safe. Another such category is air show and air demonstration pilots.

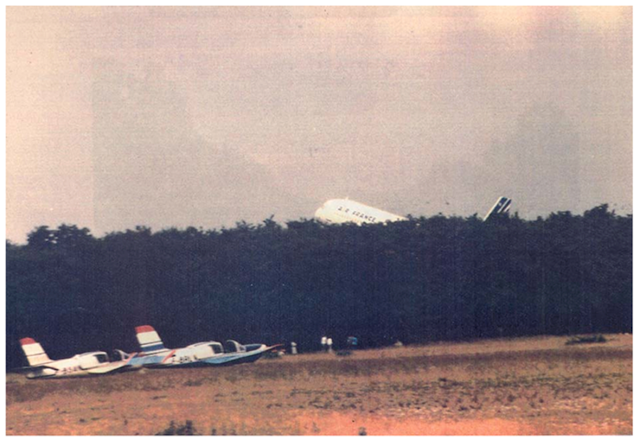

In the summer of 1988 the Airbus A320 was brand new and its launch customer, Air France, was rightfully proud of it. Flight Captain Michel Asseline was given the honor of flying a low level fly-past for an air show at the Habsheim Aeroclub in eastern France with 130 dignitaries on board. Captain Asseline was a bit of a rock star at Air France and had flown several such air shows. He was certainly qualified. But things didn’t go as planned.

The flight was planned for an overflight of the airport’s paved runway with clear ingress and egress zones. French regulations stipulated that the fly-past could be done no lower than 170 feet, but Air France rules allowed 100 feet. In any case, Captain Asseline had flown the maneuver before at 100 feet. As the crew first caught sight of the airport, they realized the airshow crowd was set up abeam a grass runway, not the paved runway. What to do?

Of course when you are a very smart and accomplished pilot, you adapt. The crew flew their fly-past over the grass runway. Of course it would be easy to excuse the crew because, what can go wrong? Well, the first thing that could go wrong is Captain Asseline dipped quite a bit lower than 100 feet; video evidence would suggest he got as low as 30 feet. He said, after the fact, that the radio altimeter was too hard to read and he was probably right. But what could go wrong? At the time he believed it was time to add go around thrust, the engines did not respond.

This very smart captain destroyed the airplane but incredibly only 3 of the 136 on board were killed. The captain was sentenced to prison for flying too low, too slow, and adding thrust too late. There is a lot of evidence that the flight data recorder and other evidence was tampered with and that France was too quick to condemn the captain in an attempt to clear the airplane. In my opinion the captain did fly too low and too slow, but I think he attempted to add power as he said he did. I do think France was eager to get this Airbus on the market with a flawless safety record and this captain was the scapegoat. So let’s cover the too low, too slow, and adding thrust too late charges.

Too low. Is the radio altimeter too hard to read? Yes, I agree that it is, especially in the likely buffeting in the fly-past maneuver. But I’ve flown many fly-past maneuvers in the Boeing 747 and I think you should be able to tell the difference between 100 feet and 30 feet. Of course there will be a depth perception problem doing the fly-past over the wide grassy area as opposed to a more narrow runway. So the very smart captain was not smart enough to realize this in the moment.

Too slow. We don’t often fly at such low altitudes, other than when intending to land, and when we do so our attention is necessarily glued outside. But something magical happens at one-half wingspan above the surface that improves airplane handling: ground effect. A smart captain can be forgiven for not realizing the stick and rudder feel would mask the lower speed of the airplane, but the very smart captain should have known better.

Too late power addition. The plan was to execute the fly-past at Alpha Max, the airplane’s maximum angle of attack which is close to but above 1G stall speed. Small turns are possible and the airplane is controllable. A smart captain knows that if anything more than modest maneuvering is needed the airplane should be accelerated. What Captain Asseline didn’t realize was that at 30 feet and in ground effect, a higher Alpha Max was possible and his aircraft’s higher angle of attack would have increased engine spool up times.

Captain Asseline has collected many defenders who argue the airplane did not behave as expected and that the French government pressured investigators to clear the new airplane quickly before sales were harmed. They might be wrong or right, but in either case the very smart captain wasn’t smart enough to execute the fly-past maneuver in such an ad hoc manner.

Mentor / Mentee

You can be the smartest pilot in your circle and you can be the smartest pilot to have ever flown your aircraft type or for your operator. But aircraft are complicated and situations are unpredictable. In aviation as with many hazardous endeavors, if you want to survive don’t get smart.

The younger generation will be tempted to look up to you and everything you say might be interpreted as gospel. It is up to you to have a reservoir of stories that bring to life that the smartest of us do not know it all and are always learning.

3

Do things for a reason

(No reason = no action)

Eighteen wheels (not all straight), four hydraulic systems (not all working), and two pilots (at odds with each other.)

When I turned 30 I got assigned to the Air Force's only Boeing 747 squadron and happily checked out as an E-4B copilot. Going from examiner pilot in a Boeing 707 to a copilot in a Boeing 747 seems like a natural thing to do. The smaller airplane was old, falling apart, and on its way out of the inventory. The newer airplane was just that: newer. A year later I was grounded with cancer and the prospects of ever getting to fly the airplane again appeared dim. But a year after that, I was back.

I was in the right seat headed to Andrews Air Force Base near Washington, D.C. as our squadron commander flew quietly. Let's call him Rodney. Rodney was a fair commander and a competent pilot. We were behind in our timing and he was keeping the airplane cleaner than normal. Rodney wisely asked for the first notch of flaps because they took a long time to extend. But that's where we stayed until hitting the glide slope. Then it was "gear down and flaps as speed permits."

We got configured and the flight engineer announced the before landing checklist was complete. What none of us knew was we had a hydraulic leak on the left body landing gear and by the time we touched down, the number one hydraulic system pressure was gone. The airplane had four different sources to each flight control axis and the worst part of losing the number one system was that it powered our nose wheel steering as well as the body gear, which were also steerable. We practiced hydraulic system failures in the simulator all the time; it wasn't a big deal.

Did I say Rodney was a fair commander and a competent pilot? That might have been charitable. Rodney touched down in a bit of a crab, despite the calm winds. That isn't usually a problem, the airplane was designed to land in a crab, though most our guys landed wing low until the crosswind exceeded 25 knots when a crab was required. The airplane has to be landed three times. First the body gear, which are attached to the fuselage and are furthest aft. Then comes the wing gear, which are attached to the wings and are forward of the body gear. And finally the nose gear. Each main gear truck has four wheels and the nose gear has two, eighteen in total.

At first, the body gear touchdown felt perfectly normal. But as the gear settled the airplane started to pull to the left. Rodney corrected with rudder and as the wing gear settled we straightened out a little but the airplane started to shudder. As we slowed the airplane shook and I could feel the left gear seem to hop in a rhythm that decreased with speed. It was like driving a car with a flat tire.

"That was fun," the flight engineer said, "let's never do that again."

"You have smoke coming from your left landing gear, do you need assistance?" asked Andrews tower.

"Tell 'em we'll clear the runway at taxiway whiskey four," Rodney said.

"I don't think we should move the airplane, sir," I said.

"We aren't closing the runway," Rodney said.

"Bad idea," I said.

"I gave you an order," he said.

We cleared the runway using a lot of thrust from the left two engines and to the complaint of the airplane in the form of groans, squeals, and that awful hopping motion. Rodney didn't mention that he didn't have any nosewheel steering but later admitted he used differential braking. Once clear of the runway we shut down and our flight engineer and crew chiefs rushed down to survey the damage.

"Pilot, crew chief," we heard as the crew chief plugged into the ground receptacle.

"What do you see?" Rodney asked.

"She's pigeon toed," he said. "You got three mains headed forward and the left body gear headed as far left as she can."

It took our maintenance team the rest of the day to repair the broken hydraulic lines. We fired up the airplane and the left body gear centered itself. "See," Rodney said, "no big deal."

A Mentor Peer

Rodney said I had done a good job and I found myself with immediate orders to upgrade. A year later Rodney was gone and I had upgraded again to instructor pilot. A year later I got another job as the squadron's Functional Check Flight (FCF) pilot. While training the outgoing FCF pilot was going over some of the major repair work done in the last few years and mentioned the "pigeon toe gear" incident.

"I thought that was no big deal," I said.

"That was the Rodney story," he said, "but it was a lie." He explained that the damage to the gear was extensive, requiring several millions of dollars in repairs and several test flights. Had the damage been properly reported, it would have been classified as an aircraft accident, and the investigation would have revealed we moved the airplane without hydraulic pressure to the body or nose gear without them being pinned.

My FCF instructor said to me, "always remember that when you get to the end of an emergency checklist, stop. If you are outside any known checklists, put the airplane on the ground and once it is there, set the parking brake until you figure it all out."

An example

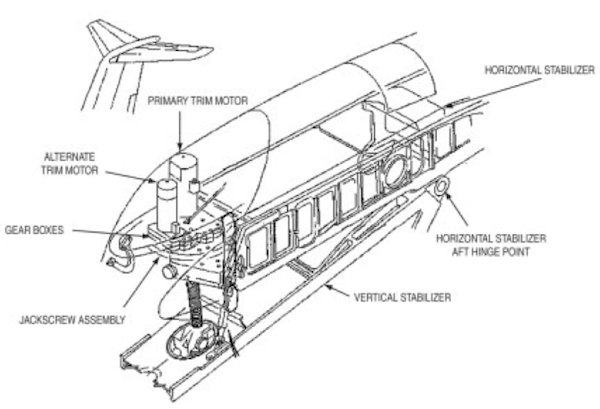

The crew of Alaska Airlines flight 261 on January 31, 2000 were set up. Their MD-80 was designed without a fail safe mechanism on the horizontal stabilizer. The lubrication, inspection, and replacement intervals on the components of the horizontal stabilizer had been extended, the jackscrew on this particular airplane was found by one mechanic to beyond tolerance but his judgment was overruled by the next.

On a flight from Puerto Vallarta, Mexico to San Francisco, California, the airplane's horizontal stabilizer froze in a slightly nose down direction while the autopilot continued to fly using the elevator only for over two hours. While climbing through 28,557 feet at 296 knots, the crew received an out-of-trim condition warning light. The crew understood the horizontal stabilizer was jammed and spent the next 1 hour 22 minutes hand-flying the airplane with between 10 and 50 pounds of pulling force, all the while trouble shooting.

As it turns out, the jam was caused by threads from what is called an Acme nut were preventing the jack screw mated to that nut from spinning. There were three methods of trimming the horizontal stabilizer: a primary trim motor activated by switches on the pilots' control wheels, an alternate motor activated by the autopilot, and by mechanical trim wheels. The stabilizer was moved with the primary trim motor during the initial climb and then by the alternate motor using the autopilot until the stabilizer jammed. The pilots ran their emergency procedure checklist, trying both primary and alternate trim systems. After several attempts of both primary and alternate systems, it appears the torque finally overcame the jam sending the airplane into a dive. They managed to regain control at a lower altitude and speed and did a controllability check demonstrating the airplane was controllable with flaps and slats. They then cleaned the airplane up.

At this point the captain proposed trying the trim system again but the first officer disagreed, saying "I think if its controllable, we oughta just try to land it."

As they again deployed the flaps and slats, the air loads on the horizontal stabilizer overcame what was left of the stop of the jackscrew and the forward portion of the horizontal stabilizer let go. At this point the pilots no longer had pitch control of the airplane, though they fought it all the way down. The television series "Mayday: Cutting Corners" (Season 1, Episode 5, 15 October 2003) provides the following depiction of Alaska Airlines 261's final moments.

There is speculation that they tried the trim system again but it is more likely that the cumulative stress on what was left of the Acme nut was just too much. In either case, the NTSB said that their use of the autopilot while the horizontal stabilizer was jammed was not appropriate and that crews dealing "with an in-flight control problem should maintain any configuration change that would aid in accomplishing a safe approach and landing, unless that configuration change adversely affects the airplane's controllability."

More about this: Case Study: Alaska Airlines 261

Mentor / Mentee

My Boeing 747 story is minor in comparison to the tragedy of Alaska Airlines Flight 261 but the lesson from both is the same: when you are dealing with an abnormal or emergency situation, do things for a reason. If you don't have a reason you can point to, don't do it. But if all that fails, as the crew of Alaska Airlines Flight 261 showed, don't give up.

4

Teaching through story telling

A personal story . . .

It is one thing to stand in front of classroom or write in a book and pontificate about what thou shall and shall not do. Saying "stop all attempts at stabilizer movement once the jammed stabilizer checklist is completed" might have the necessary impact but is more likely to induce rolled eyes and the word "duh." But told in the context of the gut wrenching ordeal that was Alaska Airlines Flight 261, the lesson has great impact and is more likely to be retained. The best instructors are good story tellers. But it goes beyond those procedures given in our manuals.

It’s all well and good to agree we should not get busy, not get smart, and that we should do everything for a reason. But sometimes we are presented a situation outside our training or we put ourselves into a situation when the three fundamental rules are in our review mirror. (We got busy, we got smart, and/or we did something without a good reason.) Now what?

One of the advantages of hosting a website with a large readership is I have hundreds of friends I've never met with open invitations for a beer or three and free advice. I was on a speaking tour on the west coast and offered to drop by an e-freind's town for dinner. As he and his wife were getting ready to meet us his kids asked where they were going. He said to meet a guy he met on the Internet.

An "E-mentor" . . .

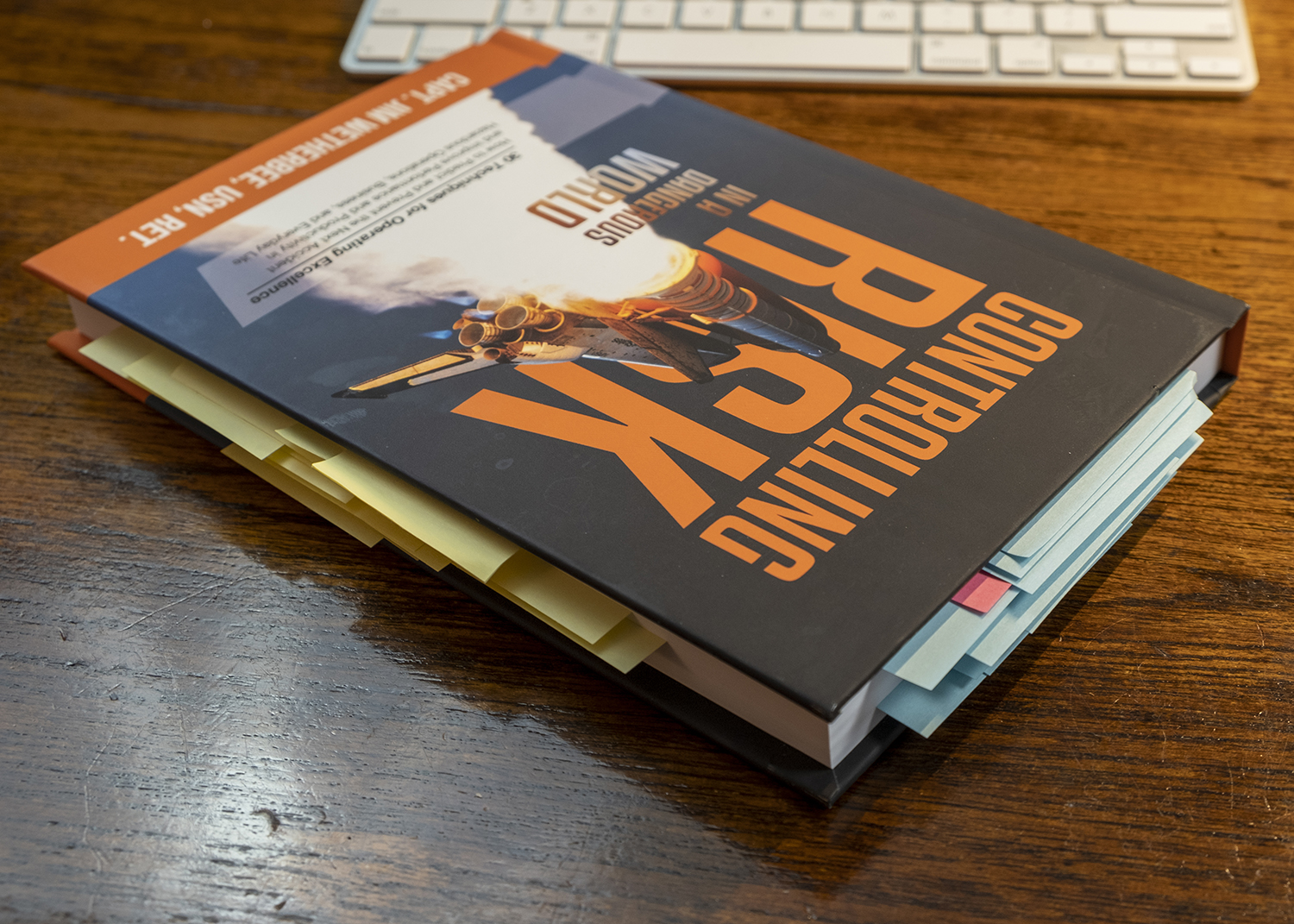

One of the guys I've met on the Internet is Space Shuttle Commander and retired Navy Captain Jim Wetherbee. He commanded five space shuttle missions and knows a thing or two about risk. He read something I wrote on the subject and sent me his book.

This is my favorite kind of book and I highly recommend it. I tend to attack these books with a pen and I used to abuse them with dog ears, a bent page. I've updated my practice with colored Post-its. A blue Post-It denotes something I want to write about. A yellow Post-It is something I think I will need for future reference. A red Post-It is something I don't agree with. As you can see, I really like Captain Wetherbee's book.

My favorite “There I was” story comes from retired U.S. Navy Captain Jim Wetherbee. Captain Wetherbee was also a NASA space shuttle commander with six trips in space, five as commander. He writes in his book “Controlling Risk in a Dangerous World” that humans learn and remember better through stories as opposed to dry facts, numbers, and rules.

Captain Wetherbee explains that in 1979 he was returning from his first deployment aboard the USS John F. Kennedy in the Mediterranean Sea. He launched from his aircraft carrier headed for Naval Air Station Cecil Field in Jacksonville, Florida. It would be his first landing on dry land in seven months, but “the runway ignored its orders and hosted a thunderstorm just prior to my arrival.” His aircraft was still set up for carrier operations, meaning the tires were filled to much higher “carrier pressure” so as to withstand the excessive forces during arrested landings, what carrier pilots acknowledge are “controlled crashes.” The downside of this higher pressure is a smaller tire contact area where the rubber meets the runway, resulting in reduced friction and less steering control during landing and rollout.

When landing on a wet runway with carrier pressure, pilots are expected to drop their tailhooks to make arrested landings. But since this would close the runway until the arresting gear is reset, pilots often choose to leave the tailhook retracted over the approach end to see how difficult aircraft control is. Some runways are set up with another arresting cable for what you might call a “second chance.”

He landed his airplane and had no problems for the first 6,500 feet of the 8,000-foot runway. After he passed the long-field arresting cable, which represented his last opportunity to drop his hook, his automatic antiskid system began to shunt hydraulic pressure away from his brakes to prevent lockup as the tires were beginning to hydroplane over the wet surface. As he puts it, “I made a bad decision on the wet runway and suddenly lost control of my $3 million, single-seat, light attack, A-7 Corsair aircraft.” He turned the antiskid system off, causing one tire to grab while the other continued to slide. “My airplane immediately turned ninety degrees to the left, and I was skidding sideways while continuing to track straight down the runway at forty knots, with my right wing pointed forward. I found myself stable yet out of control, looking over my right shoulder at the end of the runway approaching quickly, without slowing down. After a few seconds, I realized my main wheel was headed directly for an arresting gear stanchion at the runway threshold and mud beyond that. If the wheel dug in, my sidewards momentum would flip the airplane on its back. A hilariously good story for other pilots in the ready-room and at my wake.”

“As I was skidding sideways, heading for an embarrassing death, a colorful tale I heard six months earlier during our deployment flashed into my mind. In an instant, that story helped me save my airplane.”

“An F-14 Tomcat pilot was telling us about a dumb action (his words) he took during his landing on a wet runway with carrier pressure in his tires. He blew a tire, lost control, spun around, and somehow ended up traveling straight along the centerline of the runway but backward. Without thinking, he reactively jammed both brake pedals to the floorboard. Bad idea. The rearward momentum of the center of gravity popped the nose of his aircraft up until the tail feathers of his exhaust pipe scraped along the runway. His other main tire blew. Both brakes seized, and the locked wheels ground themselves down to square nubs, as his airplane came to a stop in a spray of sparks. Through all the laughter in the wardroom, he admitted, ‘Since I was going backward, rather than stepping on the brakes, all I had to do was go zone-5 afterburner on both engines.’ At the time, I joined the other pilots and laughed just as loudly at his incompetence. On the inside, though, I silently concluded I never would have thought of that now-obvious solution.”

Captain Wetherbee continues: “Back to my impending death. Without forming any words or taking any time, my brain recalled the relevant part of the Tomcat driver's story, and the automatic processing in my mind quickly invented a solution. I waited until I was approaching the final taxiway in my sideways skid. As the off-ramp reached the two o'clock position relative to my nose, I applied full power to the engine. The big, lazy turbofan spooled up with its usual delay, and by the time the taxiway was at my one o'clock position, sufficient thrust was beginning to build to push my airplane toward the taxiway. The plane exited the runway straight onto the centerline of the last taxiway before disaster. I retarded the throttle quickly, and the A-7 gently skidded to a stop, as if I had planned my graceful slide all along.”

Captain Wetherbee credits that Tomcat pilot for saving his life that day. For those of us who make a living landing only on solid land, the chances for this kind of excitement is thankfully reduced. But I hope it will cement in your brain that you have more options than nosewheel steering and brakes when it comes to controlling your airplane during landing.

Mentor / Mentee

So I've never met Captain Wetherbee face-to-face though I've talked with him on the phone a few times and have exchanged a lot of emails. And yet he has forever affected the way I fly airplanes. I've known the theory behind using forward and reverse thrust for directional control on a slippery runway for as long as I've had forward and reverse thrust. But I never thought I would have the presence of mind to remember. But now, thanks to this well told story, I think I will.

And that is the point of collecting mentors. If you can put a face to the technique, the better your chances of remembering it. And if you can place a funny, tragic, or moving story to it, I guarantee you will understand it better still. At the very least, remember that when you are dealing with an abnormal situation:

- Don't get busy.

- Don't get smart.

- Do things for a reason (No reason = no action).