"Recurrent" seems an odd way to describe regular pilot training. It implies the pilot isn't current, and now becomes current again. Or failed at becoming current, and now is making a second attempt. Whatever you call it, training in an aircraft you have already qualified to fly is a ritual we professional pilots agree is necessary, but somehow we don't know how to best make use of the time. My first recurrent was a waste of everyone's time, including my own. I quickly got into the rhythm and had mostly good but a few bad recurrents. After four decades of this, I finally got it figured out.

— James Albright

Updated:

2022-08-24

Initial and recurrent training has evolved into a simulator-only affair, made possible by very good simulators. My first flight simulator was a cutting edge technological marvel built on site at Williams Air Force Base, near Phoenix, Arizona. It was a simulated version of our primary jet trainer, the Cessna T-37B. The cockpit stood on mighty hydraulic legs and it moved magically in response to the pilot's stick and rudder. Two cathode ray tubes sat in front of the pilots, televising the view of a remotely controlled camera over a terrain board. This was pretty neat stuff in 1979.

Later that year I got my first taste of a simulator without the terrain board when moving up to the advanced jet trainer, the Northrop T-38A. The pilot's view was computer generated!

The next year I went to KC-135A copilot initial qualification. Now in the Strategic Air Command (SAC), the budget was higher and the simulator was even better. I knew that I would be training at least once every year, and looked forward to recurrent simulator training. It wasn't what I was expecting.

1 — My first recurrent (Boeing KC-135A - 1981)

2 — My best recurrent (Challenger CL-604 - 2001

1

My first recurrent

Boeing KC-135A - 1981

The low expectations placed on a copilot

Initial training for a copilot in a KC-135A back in 1979 was not only designed to turn fire breathing tigers into meek and docile sheep, but to do so in a way that prepared us for very few hours of flying time and very many, many days sitting on nuclear alert. The simulator used during initial training was on a par with the full motion simulators we had seen in the T-38, but our duties were greatly simplified.

As KC-135A copilots primarily dedicated to the ground alert mission, our jobs were to compute takeoff and landing data, run the checklists, manage the fuel panel, and fly just enough to remain legally current. Specifically, we had to fly a specified number of takeoffs, instrument approaches, and landings every six months. The instrument approaches included VOR or TACAN approaches, PAR or ASR approaches, and the trusty ILS approach. There was no weather requirement and I think most pilots availed themselves to looking out the window. I was based at Loring AFB, at the northern tip of Maine, so most of our approaches were in instrument conditions. But for many in SAC, the only real instrument time was at the simulator. We had to go to "recurrent" once a year.

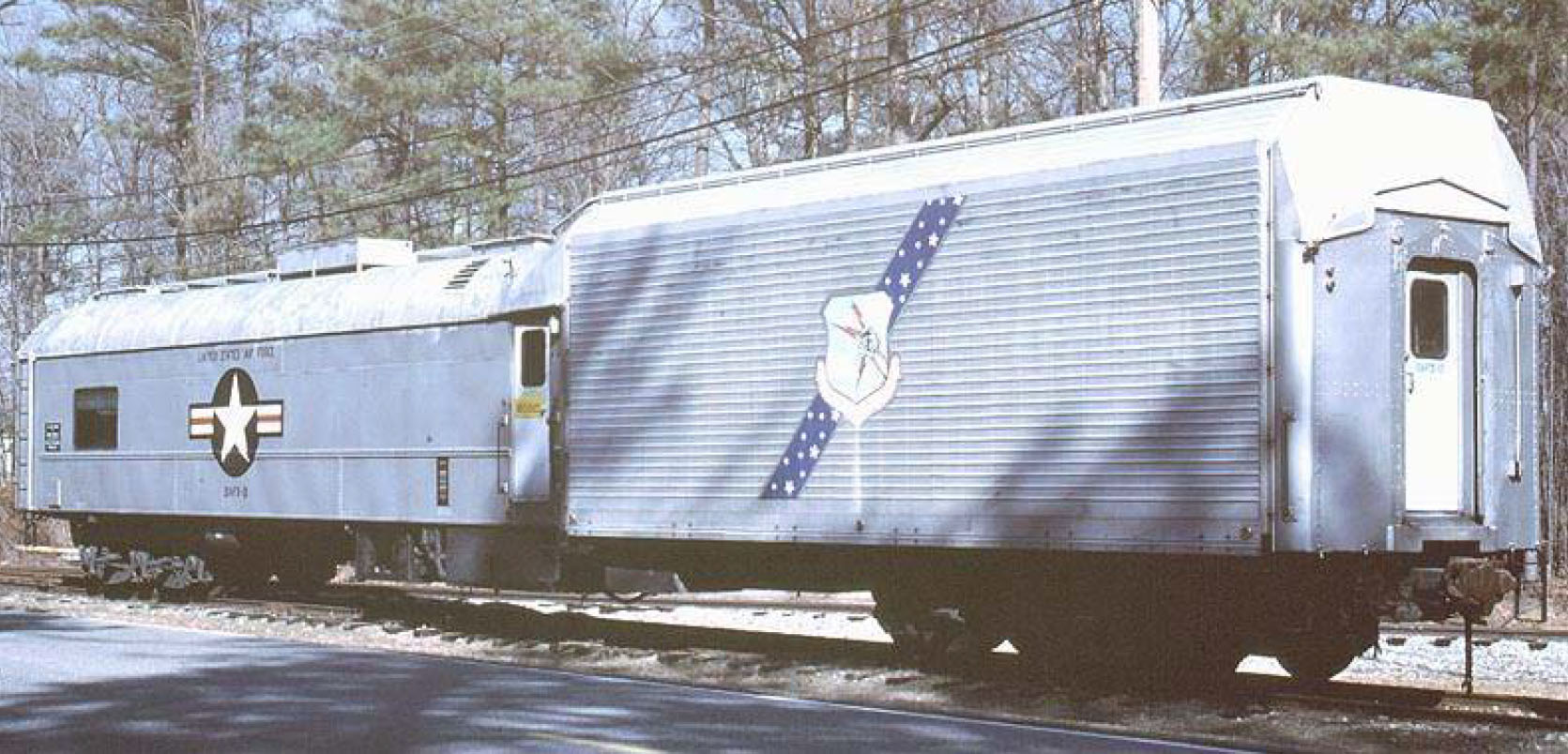

Simulator on a railcar

Instrument Flight Trainer Railcar

Chislaghi, figure 4

- The KC-135 simulator started life in the early 1960s as a Cockpit Procedures Trainer (CPT), Mission Design Series MB-26, with the Strategic Air Command (SAC). Training was aimed chiefly at ensuring proficiency on emergency procedures, especially landing and takeoff emergencies, and to conduct instrument training. Because of the number of SAC bases located across the country the user approached training with a unique concept. SAC would provide schoolhouse training at the 93rd.

- The mobile KC-135 simulators were housed in railroad cars that could be transferred around the country to provide required cockpit procedures training. One such KC-135 mobile simulator, shown in Figure 4, was moved on a routine route that included Barksdale AFB (Bossier City, Louisiana), Dyess AFB (Abilene, Texas), Columbus AFB (Columbus, Mississippi), and Bomb Wing Combat Crew Training School at Castle AFB, California with three simulators, provide seven simulators at other fixed sites, and service other operational sites with nine mobile simulators.

- Another unique feature of this simulator was the use of a crude visual display which incorporated an opaque windscreen that had lights behind it that would flash simulating lightning. The instructor, utilizing an Instructor Operator Station (IOS) was able to simulate system problems and weather but any true visual cues to the outside world were lacking.

Source: Chislaghi, §2.2.2

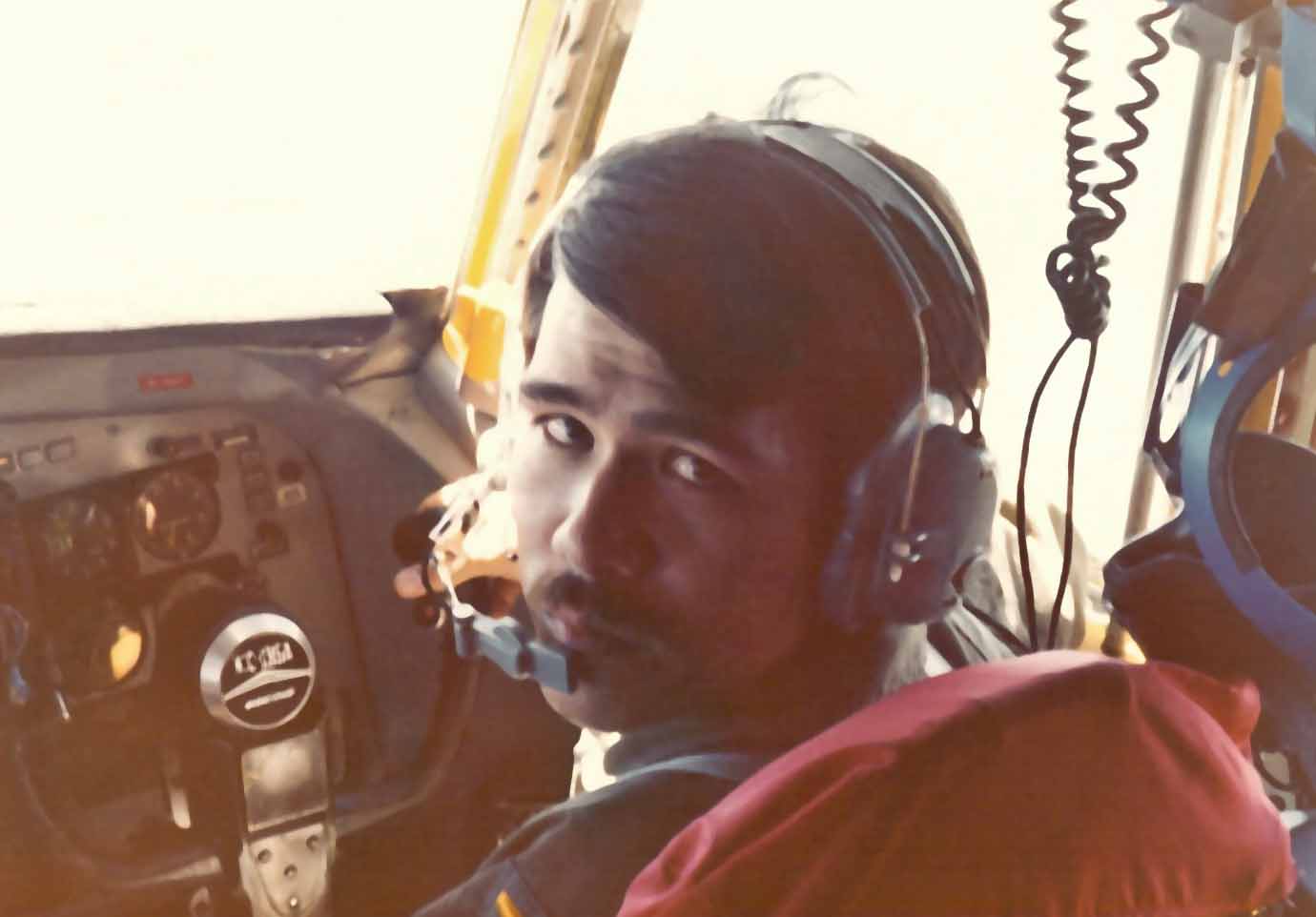

My first recurrent (KC-135A)

I never planned on going to KC-135A recurrent because I didn't know it was a requirement. Then one day my world changed after I had just come off of seven days of alert, which ended on a Thursday. "Mother SAC" gave us the next four days off and usually planned a trainer flight the following Monday. Our crew commander wasn't an instructor, so they farmed me out to another crew so I could log a takeoff and a landing once the bulk of that crew's mission was completed.

I sat in the jump seat as the instructor pilot in the left seat allowed his copilot, First Lieutenant Russell Bryant, to fly the takeoff from the right. He managed to get the aircraft off the ground but forgot to call for the flaps, but the IP got them. Russell got about 40 knots too slow on the climb. I wondered if I should have said anything but didn't. The IP blew up at Russell mercilessly and added a few barbs my way for not noticing.

For the air refueling Russell reverted to copilot duties which he managed well. (Read the checklist, manage the fuel going to the bomber, activate three light switches during the simulated breakaway.) Russell flew a PAR approach that ended with, "too low for safe approach, go around." He then flew an ILS approach that ended with the runway in front of us, so he landed. After the touch and go, the IP directed Russell and I to swap seats.

We didn't have time for me to do anything more than a visual approach and a full stop landing, which I did with no comments from the IP or Russell. As we taxied in Russell had some news. "Huge busted his sim check," he said. Huge was Second Lieutenant Hughes, but went by "Huge" because he was all of five-foot-four and couldn't have weighed more than 130 pounds.

"Sim check? We have sim checks?"

"Yeah, sim check. Don't you know nothing?"

I knew some grammar, I thought, but didn't say. "We have to take sim checks?"

"Don't you know nothing?" Russell repeated. "You gotta do the simulator once a year. That's a two day thing. One day for learning and one day for checking. Don't worry about it. Nobody ever busts. Well, almost nobody."

Russell was so surprised by my reaction that he asked the squadron schedulers about me; they discovered I was overdue my sim check and canceled my next flight so I could go to the two day program right on base.

I learned that the KC-135A simulator was in a railcar that in theory was meant to travel between several SAC bases, but in practice ended up being permanently stationed at our base because enough SAC bases had closed to free up a railcar for our base to call its very own. On the appointed day I drove up to the railcar and found the parking lot empty and the front door was locked. It was summer in Maine, which meant the temperature was above freezing but the mosquitoes we in attack mode, so I retreated to my car and waited. As a military pilot, a scheduled event is never optional and if the event was at 0900, I was going to wait until 0905 before retreating. Or may 0915. As if reading my mind, the simulator instructor pulled up at 0910. He drove a rusty brown Datsun pickup truck with no front bumper and half of one on the back. I got out of my car and looked up to see First Lieutenant Russell Bryant. I saluted. "You going to school too?"

"Me?" he said while returning my salute. "No, I'm your instructor and examiner. So you best be calling me 'sir' from here on out."

There is a school of thought that second lieutenants don't owe any military courtesy to first lieutenants, but I never subscribed to that.

"Yes, sir," I said. "Are you really my instructor today?"

"You bet, let's get this over with."

He unlocked the front door and directed me to a chair in a classroom designed for ten. He fired up an overhead projector and read from a book about aircraft systems for the next hour. When he was done he asked, "any questions?"

"No, sir."

"Go get some lunch, then. I'll see you back here at 1300 for the sim."

I looked at my watch. A three hour lunch? I drove home. At the appointed hour, I drove up and parked alongside Russell's pickup truck. Wandering through the classroom railcar I heard the buzzing noise of air conditioning to one side. Following the noise I was led to a narrow hallway that ended with a door to the next railcar. Behind the door I found what looked like a KC-135A cockpit, chopped off from just behind the pilots' seats where sat a small control panel, a desk, and Russell. "Come on in," he said. "You ever flown from the left seat?"

"No, sir."

"Well now's your chance. We just need to see one takeoff, a precision approach, a non-precision approach, one emergency procedure, and a landing. Then we'll call it a day."

For the next hour I fumbled through the engine start procedures, taxi, and takeoff. The novelty of doing this from the left seat made it fun, but I wasn't really learning anything I needed to be a better copilot. The "simulator" didn't have a view outside the windows. Flying from the left seat and with my left hand as opposed to the right seat with my right hand wasn't the challenge I thought it would be, and each approach went well.

The KC-135A autopilot couldn't fly an approach but the flight director was quite good. As long as you got the aircraft configured and on speed, it was stable enough during an instrument approach. Unlike the aircraft in my future, the simulator flew better than the airplane.

After the third approach, Russell said, "Pretend you see a runway and go ahead and land." I did that. "Nice job. Let's go to the O'club and debrief."

"I thought we had to do some emergency procedures."

"Oh, I almost forgot," Russell said, sidestepping the fact he had forgotten. "Okay, let's takeoff again and climb up to 10,000 feet."

As before, I went through the left seat motions as Russell knelt behind the throttle quadrant and reached forward to move the gear handle and flaps when I called for them. Reaching 10,000 feet he asked for me to engage the autopilot, set the throttles to maintain 300 knots, and the heading bug to steer us straight ahead. I did all that. "You see the new weather officer yet?" he asked.

"What?""

"They call her Wicked Wendy." Russell went on to give me the entire history of women in uniform as I started to wonder about emergency procedures and reached for my plastic bound checklist. As Russell reached the Civil War in his chronology of the sexes, I smelled something along the lines of burnt grease but sweeter. Having spent some time with a soldering iron in my hand, I recognized the smell of burning electrical insulation. Then I spotted the first wisp of smoke.

"I think the simulator might be on fire, Russell."

"It's an airplane, stupid. What are you going to do?"

I pulled out the checklist and followed each step, directing the boom operator to fight the fire, the navigator to plot a course home, and the copilot to help me with the steps needed to deal with an electrical fire. "Good enough, now let's head to the bar."

I unstrapped from my seat and saw a metal pie pan sitting on a hot plate plugged into an extension cord. The pan was charred black. "I thought of this myself," Russell said. "Neat, huh?"

"Unless its toxic, sir."

I managed to endure a beer with Russell at the Officer's Club and he let me know that he was allowed to deem the day's ride good enough to pass for a check ride and he so deemed. My first KC-135A recurrent was complete with a generic "PASS" on my record. I vowed to never do another. Within six months I had orders to my next aircraft and would never again set foot in the KC-135A simulator railcar.

2

My best recurrent

Challenger CL-604 - 2001

The "captain"

My first civilian job was to fly one of three Challenger 604s for Compaq Computer out of Houston Intercontinental Airport, Texas. Though I understood I would be quickly upgraded to captain, I would start out as a first officer. My training, however, was as a captain and the initial syllabus was designed around that fact. The training was quite good.

The simulator is an airplane

“The simulator is an airplane,” we were told on Day One, “you are to treat it that way. If you wouldn’t do it in an airplane, don’t do it in the sim.”

I was to find out the CL-604 simulator flew very much like the airplane, except the sim was more forgiving than the airplane in a gusty crosswind. The emergency procedures were immersive, in that you could easily lose yourself in the event and the training was well worth the time. I left the training feeling fully ready to fly the airplane but fully unprepared to handle the high-tech avionics.

In the six months to come I would learn what I needed to conquer the avionics, upgraded to captain, and completely forget to keep in the books. I was on the road 20 days each month and opening the flight manual was the last thing on my mind. My first recurrent as a civilian was notable because I was told that I did well, but knew that I did not. Every topic during ground school revealed to me all the things I once knew but had forgotten. I somehow got 100% on the written exam, but many of my answers were guesses. I had relied on luck. My simulator performance garnered several “good enough” results and one “let’s try that again.” If I were to have administered my own check ride, examiner-me would have told examinee-me that I was getting a “gift pass,” only because I knew examinee-me was new to the jet and must promise to do better next time. I vowed to do just that.

My best recurrent

I instituted a weekly regimen that included one aircraft system to dive into, a normal procedure to study, an abnormal to fully explore, and several blank pages in a notebook to fill with it all. It was a zeal I had never before applied to aircraft study fueled by the embarrassment of the gift pass. Six months later, I showed up for recurrent smarter than the day I left initial.

Our ground school instructor was a pilot with thousands of hours in the CL-604, which was quite a lot for an airplane that had only been certified a few years before. He would have still been “out there” in the real world, but had lost his medical to “a faulty valve in what the doctors say is a heart in my chest cavity but my three ex-wives tell me doesn’t exist.” He would talk without notes, flipping through slides on a projector, running through mandatory topics and throwing in a few not in any textbooks but from his experiences on the road. He ended each class hour with questions for us students. Correct answers were rewarded with “Very good.” Wrong answers got a quick nod to the next pilot and a “what do you have to say about this?”

After the third class session one of my correct answers got a warm, “Excellent. You haven’t got anything wrong yet,” and he moved on. At the conclusion of the second day, it was exam time. Every question had been covered in class and getting 100% only required that you had paid attention. After the instructor returned my grade sheet, he said, “Well done! It has been a pleasure.”

I heard that my simulator instructor, Mark Black, earned “instructor of the year” honors two years ago and would have repeated last year but the company decided it would be demoralizing to his peers. Mark had also been “out there” but tired of the days away from home and decided that Tucson, Arizona was as good a place as any to plant roots for his family. He still flew and became a highly sought after contract pilot. He started each of our three days with a mini-ground school of sorts, beginning with a quiz of material in the books. If my sim partner or I produced the right answer, he would expand on each point with information not in any of our books.

“What is your approach category?” Mark asked, looking at my sim parter.

“D,” he answered.

“Our VREF is usually around 130 knots,” Mark said, looking at me. “What is the upper limit of Cat C?”

“One-forty,” I said. “But the manual says we circle at 150, so that makes us Cat D.”

“Why do we have to circle at 150?“

I didn’t know. Mark gave us the history of the aircraft when it was allowed to circle at VREF. It wasn’t good.

As smart as my sim partner was, his stick and rudder skills were poor. He admitted to only flying once a month and only half that time in the left seat. I managed to do a fair amount of instruction from the right seat and the first session went well. After we swapped seats, I caught him rushing through emergency procedure checklists and either skipping steps or taking a wrong turn in the Byzantine instructions. I had studied them so often, I had parts memorized. By the third day we were working as a team and breezed through the check ride.

“Outstanding!” Mark said as he signed my paperwork. “Best I’ve ever seen.”

I thought I had broken the code. My knowledge level was high, due to my recently adopted study habits. My proficiency was also high, due to the schedule. I vowed to keep it up . I did not.

3

My worst recurrent

Gulfstream G550 - 2009

During the next three years, I managed one good recurrent after another. I stopped the weekly study regimen but managed to coast along. It had gotten easy and I longed for a change. I got my wish with a move to the Gulfstream GV, where I repeated the unprepared, “I shall do better,” doing better, and then coasting along cycle. After my company went out of business, I got hired as a check airman for a new outfit. I went to Gulfstream G550 initial, but for the next year only flew from the jump seat.

Gulfstream G550

Matt Birch (http://visualapproachimages.com/)

That company went out of business after a year and I got hired by another. They sent me to G550 recurrent at a vendor I’ve come to call “Brand X.” Ground school was a joke.

Them: “When does the ‘WING HOT’ light illuminate?”

Me: “At 180 degrees.”

Them: “No. Try again.”

Me: “At 180 degrees Fahrenheit.”

Them: “No. Why do you have to make things so complicated. I am only going to ask once more. When does the ‘WING HOT’ light illuminate?”

I pondered that for a few seconds.

Me: “When it’s hot?”

Them: “Yes! Finally!”

Having survived ground school, I was turned loose on the sim. My instructor was William “Don’t you dare call me Bill” Sevrins. William had been violated, lost his job, and could only find work at Brand X. My sim partner, Carl, was a youngster with just ten years as a pilot and only two of those flying Gulfstreams. For our first session on our first day, Carl was doing a great job but I was just barely keeping up. After a year of not flying from either pilots’ seats, I had forgotten how to program a holding pattern from our current location, something known as a “present position hold.” I immediately fessed up. “Can you walk me through this?” I asked. “I forgot how to do this.”

“I can’t believe this,” William said. “Everyone says you are good. I guess everyone is wrong.”

From that point I could do no right. Much of the fault was mine, I wasn’t proficient and I clearly had not been in the books. But at least I could fly the aircraft. Or so I thought. My initial takeoff was textbook perfect, as were all of the following all-engine approaches. For the engine failure after V1, I kept the airplane straight with just the right amount of rudder, rotated just right, and then all hell broke loose. I added a little rudder but it was too little, too late. I added more rudder but it was too much. I was all over the sky. “Let’s do that again,” William said. “But try to have some finesse this time.”

As William reset the simulator my mind raced. Why was the maneuver that troubled so many now bedeviling me, having mastered it so early in my career? My next attempt was no better than my first. “Good thing this is day two,” William said. “You need to sort this out.”

I went back to the hotel with my tail between my legs and contemplating busting my first check ride after twenty-plus years of flying jets. I pulled my notebooks in search for anything about how to survive an engine failure at V1. My notes from the GV had the key. “The airplane is so overpowered you are going to end up with the good engine at full power, but that is too much when still on the ground. You will have barely a quarter of the rudder with all three gear on the runway. Once airborne you are going to need all the rudder. Plan on it. Rotate and smoothly add all the rudder in one motion. If you wait for the yaw to develop, it will be too late.”

The next day I watched with satisfaction that the nose behaved. “Better,” William said. During our final critique William heaped loads of praise on Carl. He had great instrument skills, his procedural knowledge was tops, and it would be a pleasure to fly with him again. They shook hands. For me, William produced my paperwork and said, “see you again in six months.”

It was a tougher rebuke than a bust, having wounded my self-perception as a “better than good” pilot and reducing me to one of the mortals lucky to scrape by. I returned to my old weekly study routine and thankfully never again heard the words “you need to sort this out.”

4

Recurrent, the right way

Gulfstream GVII - 2019

First recurrent in a new jet while still flying another jet

Gulfstream G500

Matt Birch (http://visualapproachimages.com/)

In 2019, I attended Gulfstream GVII initial training. I was in the tenth class ever held and the aircraft was still awaiting certification. In the meantime, I was still flying the Gulfstream G450, which I had flown for ten years.

It was one of the best initials of my career, exposing me to technology I had never seen before, introducing me to some of the finest instructors I had ever known, and whetting my appetite for the new airplane. I write about that here: Introducing the New Jet.

Six months later, it was finally time to take delivery. We had a second pilot just graduating from initial and I was happy to attend my first recurrent in the new jet, even though I had never actually flown it. I wanted a refresher. I was, for the first time ever, worried about not measuring up at recurrent. I had been flying the wrong jet for six months and was so busy in the process of buying the jet, I hadn't given any thought to flying it. With only 30 days to go, I realized I needed a crash course of self study to get my mind right.

Recurrent, the right way

Limitations

My first challenge was to re-memorize aircraft limitations. Fortunately, I had written a full set of iPhone flash cards and published those: Quizlet G500 Limitations.

Systems

With 29 days to go, I didn't have the limitations memorized but I was on my way. I started pondering aircraft systems and realized I had a lot of ground to cover. The new jet's systems have some things in common with the old jet, but Gulfstream rightfully claims it is a "clean sheet design." Placing the systems of the new jet in order of complexity and "strangeness" compared to the old jet:

- Electrical system

- Fuel system

- Hydraulic system

- Flight control system

- Fire protection system

- Powerplant system

- APU system

- Landing gear and brakes system

- Pneumatic system

- Air conditioning system

- Pressurization system

- Ice and rain protection system

- Oxygen system

- Water and waste system

That list is 14 items long, so it made sense to devote a day to each system. That would give me 15 days for whatever came next.

Procedures

After seven days of studying systems I was getting into the groove and realized the remaining systems topics did not each deserve a day of their own and that many of the systems I had relearned begat new procedures I had to get re-familiar with. (There are well over a hundred normal and abnormal procedures.) So, with 21 days left, I decide to give the remaining systems a half-day each and started to dive into the many procedures I would have to know.

Themes

With a week to go I felt that I was ready to show up at recurrent as if I had been flying the jet all along but not necessarily ready for what the instructors would throw my way. Thinking back to all the recurrents in my past, there were "themes" the schools like to emphasize:

- Stalls, Unusual attitude recovery

- High, Hot, and Heavy takeoff operations

- Cold weather operations

- Low visibility taxi, takeoff, landing

- Fires, engine and cabin

- Windshear and Controlled Flight Into Terrain avoidance

- Performance (takeoff, landing, weight and balance)

So I spent the next seven days with a day dedicated to one of those themes.

And . . . did it work?

There are few more satisfying training events than one where you come away feeling you’ve learned something new, and you performed above and beyond the standards of the course. For my first GVII recurrent I felt a little behind in knowledge, a little ahead in stick and rudder skills, and comfortable in the jet. The airplane was so new that many of the procedures taught during initial had been superseded. And, of course, I had yet to fly the airplane. But I chalked it up as a win. Five months later, now actively flying the airplane, I retried my 30-day preparatory program and found that I was well prepared and able to maximize recurrent. I wish I had figured this out back in 1981!

For more about how to build your own 30-day program: Preparing for Recurrent.

References

(Source material)

Chislaghi, Don, Dyer, Richard, and Free, Jay, KC-135 Simulator Systems Engineering Case Study, Air Force Center for Systems Engineering, 2010