Imagine an approach briefing that was so complete, it included the frequencies of all the navigation aids, each of the initial, intermediate, final, and missed approach altitudes, every depicted course, and even the date of the chart. Now consider that this might be perfectly appropriate for some airplanes and actually detrimental in others. How can that be?

— James Albright

Updated:

2020-12-19

Many non-pilots are fond of saying "less talking, more doing." Pilots realize that sometimes a good briefing, even to yourself, can make the doing easier. This is especially true on a crew airplane. The problem, however, is some of the talking becomes so monotonous, so repetitive, that it can be tuned out. Have you ever given an approach briefing, for example, and thought that you've already given it? Or have you given a before takeoff briefing that meticulously covered the departure procedure, but then forgotten your plan while actually flying it? Me too.

1 — Short story: How I got here

1

Short story: How I got here

My first crew airplane was the Boeing KC-135A tanker, operated by the Strategic Air Command back then. SAC was highly standardized and there was a checklist for everything; all briefings were according to a checklist and there wasn't much room for creativity. This seemed to work back then in SAC, because just about every takeoff and landing was at an Air Force base. From there I went to the Pacific Air Forces flying a Boeing EC-135J where we flew to a much wider variety of airports and were no longer shackled by the SAC way of doing things, and crews pretty much operated the way their individual crew commanders wanted. Things got hectic at times and they certainly didn't run smoothly all of the time.

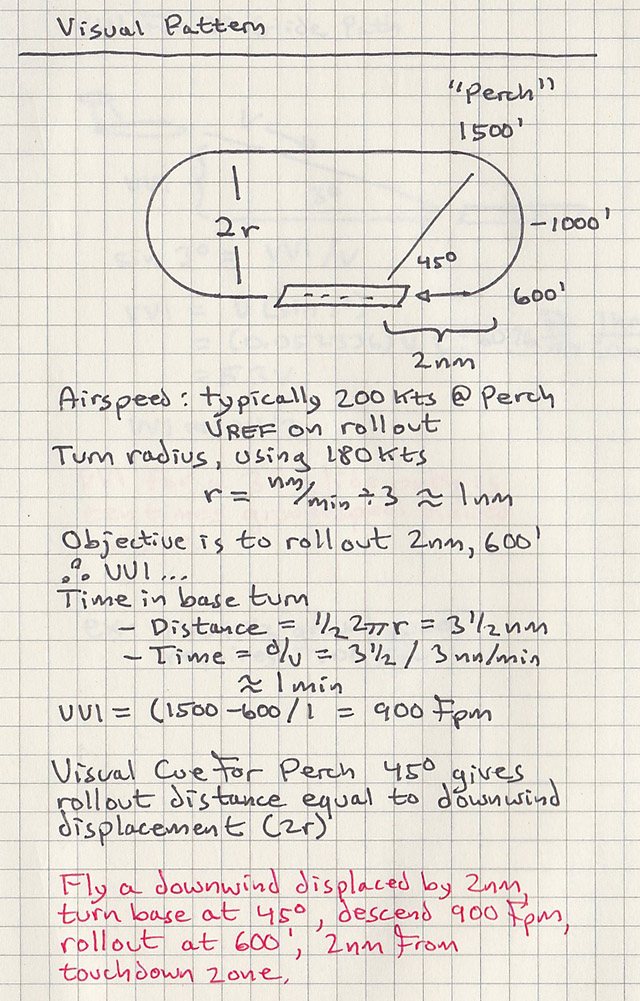

I became an instructor pilot in 1985 and after doing that for a year was sent to the Air Force's Central Flight Instructor Course (CFIC) where we learned to cram as much instruction into a VFR or IFR traffic pattern as was possible without breaking the student or the airplane. The student, however, was considered expendable. (CFIC motto: "See If I Care") One of the techniques was to have a script for everything. Let's say the student has difficulty descending from downwind to final and tended to roll out too high. You, as the instructor, didn't have the time to come up with the right words in the moment, you had to have them memorized. So that's what you did. "You ended up steep on final because your descent rate during the base turn was a bit shallow. The added drag of the gear and flaps will start the airplane down so you don't need to touch power. Since you are starting from 1,500 feet and want to roll out at 600 feet, you need to lose 900 feet. You can check your progress halfway through the turn where you should be around 1,000 feet. If you aren't, you can adjust during the turn." You had a script for dozens of situations.

After a while this sort of instruction crept into other areas where you had a script for your non-instructor tasks too.

My next airplane was the Boeing 747 where I found having these scripts made life easier for the wider variety of activities. That is where I settled on a takeoff briefing that stayed with me for the next 30 years.

"This will be a rated thrust takeoff from the left seat. My hand will be on the tiller through 80 knots. If anything happens prior to 80 knots, say the word abort and if you do, I will. Beyond 80 knots, if we have a loss of thrust, directional control, a fire anywhere on the aircraft, or any condition where the aircraft will not fly, say the word 'abort' and if you do, I will. Beyond that, we will take the aircraft airborne. An emergency return here is a good option. Do you have any questions or comments?"

The only thing different about this in the 747 and all the airplanes that followed was the 80 knots in the script began as 100 knots. If the rest of the cockpit crew is in training, I would change the 'say the word abort and if you do, I will' phrase into 'announce the nature of the problem and I will make the decision to abort or to continue.'

What's wrong with all this?

You can imagine that after 30 years, the briefing just rolled off my tongue. I've taken a number of check rides where the examiner was so impressed that he asked me to write it down so he could adopt it. The problem was that after listening to it over and over again, people I flew with often started to tune it out. In fact, I was tuning it out.

The other problem was that this became the expected briefing and once completed, everyone considered it complete and there were almost never any questions or comments. I gave the briefing in a Gulfstream GV just prior to taking off from Eagle Airport (KEGE), near Vail Colorado, where the cloud cover obscured some very large mountains in our takeoff path. We had procedures in place to avoid the mountains following an engine failure, even at night or in the weather. But I hadn't mentioned them. If we had lost an engine just after V1, we would have had to do everything just right to survive. But I never mentioned them at all. That silver-tongued briefing would have done us no good. The NTSB would probably have made a comment about how poetic that briefing was. Poetic, and useless.

Recent Innovation: threat forward briefings

The Royal Aeronautical Society published an excellent article called Briefing Better making many of these points. They note that in the crash of UPS Flight 1354, the crew's arrival briefing prior to their controlled flight into terrain was nearly perfect. Perfect, that is, as defined by their company's standard operating procedures (SOPs). This led to several conclusions:

- The crew did not discuss the relevant threats in the approach to come.

- The crew did not consider countermeasures to address those threats.

- The briefings were from decades-old formats that did not make use of next generation flight decks.

- The briefings were too long.

- The briefings were one-sided affairs with one pilot talking and the other listening.

The article's authors came up with four goals for their briefings. First, following the law of primacy, information presented first is better retained, the relevant threats should be discussed first, followed by specific countermeasures. Second, the briefing should be interactive. Third, the briefing should be scalable, you should be able to shorten or lengthen the briefing as needed. And finally, the briefing should be cognitive, the concluding item is also well retained.

2

My Take: "OPT" for something better

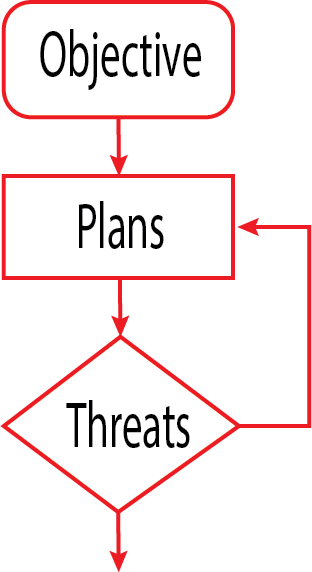

While I agree that threats and countermeasures are important, I'm not so sure they should go first. I think we need to focus on the task at hand: why are we about to do this? Then how are we going to do this and are there other ways to do it? With those steps out of the way, we can analyze the threats as they apply to our plans and come up with countermeasures. If the threats are too great and the countermeasures are insufficient, we need to rethink the plan.

- Objective — What are we trying to accomplish? This should be stated at the most "primal" level. In other words, our objective may be to get passengers from Point A to Point B. Getting the airplane from Point A to Point B might be part of the plan, but unless the airplane needs to be there for maintenance or similar reason, it is probably not a part of the objective.

- Plans A, B, C . . . — How are we going to achieve the objective in an ideal circumstance? This is what we want to do for a variety of reasons: efficiency, economy, or even because "we just want to." What if things are not ideal? Then what?

- Threats / Countermeasures — What threats can prevent or hinder our desired plan and how can we make adjustments to mitigate those threats? If the original plan cannot handle the threats, we revise the plan. We do this over and over again until the plans are deemed sufficient.

3

Pre-trip briefing

The pre-trip briefing is something we often skip, reasoning we've done it before and everyone already knows what to do. But when we do that, we risk forgetting something beyond the next flight, since that is where our focus tends to be. On a week long trip, for example, will we be thinking about due dates several days into the future?

- Objective — The reason the trip is taking place shouldn't be confused with the reason why YOU are flying a trip on YOUR airplane. The reason the trip is taking place is that your passengers (or cargo) needs to be someplace in a timely manner.

- Plan A — You want to fly your passengers as scheduled because that is why you have a job, it is your raison d'être, the French would say.

- Threats / Countermeasures — The plan under consideration needs to be examined next to the environment and any conditions that may threaten its accomplishment. If a countermeasure can be introduced to mitigate the threat, the plan can be adjusted. Otherwise, a new plan is needed. As much as you might hate the idea, given the objective, the new plan may be to airline the passengers instead. The AWARE acronym can be used to consider possible threats:

- Aircraft

- Weather

- Airport

- Routing

- Extras

More about AWARE: Prebrief / Postbrief.

Example Scenario

PIC: "We are taking the company CEO and COO from Bedford to San Francisco for a meeting that takes place tomorrow and then to a three-day conference in Las Vegas the day after that. The conference ends on Friday and we return late that evening. Our plan is to fly the trip as scheduled. Are there any threats to consider?"

SIC: "The aircraft looks okay with no MEL items but I think our navigation database expires on Wednesday. The weather might be an issue today because the airport hasn't got any of the runways plowed yet, but it appears the snow has stopped and they hope to have them open in time for us. We've been to each airport on the schedule and they seem to be okay, no real NOTAMs to worry about. I see you've flight planned normal high altitude routes. We don't have any catering requests for the legs after today, so we might want to ask the passengers about that."

PIC: "Good points. Let's give our dispatcher a heads up that if our runway doesn't open in time, we might need to arrange airline travel out of Boston Logan to get the passengers on the way for tomorrow's meeting. We can catch up with them before the San Francisco departure. But if the passengers are okay with a delay, we'll leave as soon as we can. Let's verify the navigation data base. If it does expire on Wednesday, we don't have time to fix that before we depart. Since the database is good through our flight into Las Vegas and we have two days off after that, let's have our mechanic meet us or arrange for a contract mechanic on Wednesday. Since we are in a warm hangar and it is a bit foggy out there, we might want to look at anti-icing."

Notice that we were able to adjust Plan A with a countermeasure to defeat each of the threats.

4

Pre-flight briefings

The pre-flight briefing is a subset of the pre-trip briefing, so your focus narrows a bit. But the steps are the same. We have been using the "AWARE" acronym for years, but that is primarily a threat briefing. There are steps before and after AWARE. More about AWARE: Prebrief / Postbrief.

Example Scenario

PF: "The good news is the runway just opened but the bad news is it is snowing again. We will be departing IFR due to a low ceiling and the light snow fall. I called the FBO and they have Type I and Type IV available; their truck will meet us at the de-ice pad. What are the threats, as you see them?"

PM: "We have to remember that we need to have the wing anti-ice system on at least four minutes prior to takeoff and have a limit of twenty minutes with the system on. Tower may not know that about our aircraft type."

PF: "Good point, I'll give them a call. We should review the procedures while we get a chance."

5

Before takeoff briefings

We've adopted a "threat forward" approach to the takeoff briefing but I think I am ready to adapt it to a hybrid of the old and the new. Briefing only the threats has made me rusty on things I shouldn't be rusty about. Takeoff happens so quickly in many aircraft that you need to have certain procedures in mind without hesitation. In our GVII, for example, the aircraft does a great job of filtering information from us during the low and high speed portions of the takeoff. But there are things that don't happen with a CAS chime that will require an abort. I think I will bring back some of my old takeoff briefing. Some of the threats to consider:

- Departure Obstacle Analysis as well as any performance data.

- Engine out performance.

- Initial routing turns, altitude restrictions, and speed constraints.

- Runway Condition Assessment Matrix, including the ability to maintain directional control as well as stopping capability.

Example Scenario

PF: "This will be a rated takeoff on a recently plowed runway. The airport is calling it 5/5/5 and our performance numbers reflect that with cowl and wing anti-ice systems on. Our de-ice is complete, we've completed a tactile check, we have our four minute requirement met, and tower says we'll be cleared to takeoff once we get to the runway. We will abort for anything below 80 knots, and from there to V1 for any reduction in thrust or directional control, for a fire, or for any double or triple chime. After V1 we go airborne. An emergency return here is possible, but Manchester or Logan might be better options. Are there any other threats to consider?"

PM: "Only the twenty minute limit on our wing anti-ice. If we get word of any delay, we can turn the wing anti-ice off. But when we turn it back on, we need another four minutes. That might be a good time to do another tactile inspection."

6

Approach briefings

My first crew aircraft was the mighty KC-135A tanker, where we had two pilots and a navigator up front. Each of us had our very own book of USAF approach plates, clipped to the yokes for the pilots and placed on a table for the navigator. We started the briefing by checking the date of the book, then we read the top line of the particular plate, and then we covered the frequencies, altitudes, and the entire procedure. We basically covered it all. It often took five minutes to do. All of this made some kind of sense, in that we didn't have an FMS to fly the approach and the autopilot wasn't to be trusted. We had to dial in the frequencies, fly the courses and altitudes, and to make sure we were all on the same page.

As I write this, my last recurrent was flying a Gulfstream GVII-G500 and my simulator partner was a FlightSafety G500 instructor. When I gave my approach briefing, about all I said was "This will be an ILS to minimums, we are looking for a full set of lights, if I get any lights on the EVS I'll announce that and land unless you don't see the runway by 100 feet. Our biggest threat is the low visibility. Any questions?" There were none, and it all worked out. We took a break and traded positions. The FlightSafety Instructor, now in the left seat, gave a complete approach briefing that would have elicited applause from a Strategic Air Command evaluator. He started with the date of the chart, which was on the cockpit avionics we both had in front of us. He covered the frequencies, which the avionics set for us. This went on and on. So was he right? Or was I?

If you are flying an airplane without an FMS or other avionics that take care of many of your housekeeping chores, maybe briefing all that makes sense. But in my airplane it is a distraction, diverting your attention from where it belongs.

If, like me, you are flying something more automatic than my ancient KC-135A, I think the best way to do this is:

- Both pilots discuss the approach options and agree on how to proceed.

- The PM programs the FMS and checks the program procedure against the approach plate. If frequencies and courses need to be manually set, the PM should do that as early the situation permits.

- Both pilots should independently (and silently) study the procedure.

- Once ready to brief, the PF should cover the procedure using the FMS while the PM verifies using the approach chart.

Example Scenario

PF: "We are hitting San Francisco on a rare IFR day and the ATIS is calling for the ILS to Runway 19 Left. I see the approach is programmed and the plate is displayed. The FMS has us arriving at SHAKE at 2800 feet which is below the MSA in all sectors so we need to keep an eye on the terrain when on vectors. The FMS then gives us a 3 degree glide path to DA of 300 feet. I see you also programmed an alert height of 111 feet. We will look for the MALSR lights and a PAPI on the left of the runway. If we have all that the runway is wet but our performance using Autobrakes medium takes only half the runway. The turn off could be left or right, so let's keep on top of that. The FMS shows the published missed is a climb to 520 feet then a left turn onto the SFO 101 radial at 4,000 feet. What are the threats we need to consider?"

PM: "You've already mentioned the terrain on the approach but we need to be aware of the terrain west of the airport prior to the left turn on the missed approach. We can't delay the left turn."

PF: "Good point. It is a 90-degree turn to the left at the missed approach point."