“Live fast, die young, and leave a beautiful corpse.”

— Attributed to James Dean, but first written by Irene Luce, 1920

I’ve heard this saying from a few pilots over the years, “I want to live fast, die young, and leave a good-looking corpse.” But we know, or we assume, this is a joke. Corpses, especially in aviation crashes, are rarely good looking.

— James Albright

Updated:

2023-07-15

The problem for those of us flying professionally is that the person in back, the one paying the bills, might believe in and live by the tired old saying. Even though you are in control of the airplane, the pressure from the hard charger in back can influence you in ways you don’t recognize. I’ve experienced this on a small scale in the military, and again as a civilian flying for rock stars or the mega rich. In each of these cases, I’ve heard stories which made my experience seem trivial. No matter where you find yourself in this range of idiocy, you should consider giving up that high paying job for one that may outlast it and improve your odds of leaving a good-looking corpse.

2 — A more tragic Air Force example

4 — A few more rock star examples

1

My Air Force example

With barely 300 hours in my logbook, I was a second lieutenant copilot flying from the jumpseat of a KC-135A tanker with a one-star general in the left seat and an instructor in the right. The senior officer had flown the takeoff from Anderson Air Base, Guam, and got us up to altitude on the way to Diego Garcia, a flight of 13 hours. He let the speed creep up to Mach 0.79, almost our maximum. The instructor sat quietly in his seat, leaving me no choice but to speak up. “We need Mach seven five, general.”

The general cast a sideways glance to me and then to the IP. “No,” is all he said. “We are going swimming then,” I said. The general unstrapped and as he got out he said to the IP, “give this a lieutenant a lesson in officership.” “Yes, general.”

After the general left the cockpit I strapped into the left seat and put my hands on the throttles. The IP said, “slowly. We don’t want his royal highness sensing the power being pulled.”

“What about officership?” I asked.

“The laws of physics outweigh the laws of officership. Don’t ever forget that.”

2

A more tragic Air Force example

A few years later I attended the Air Force Flight Safety Officer Course, which was a nearly three month affair with all sorts of classes on everything from math intensive aeronautical engineering to psychology-based human factors. The most interesting class, by far, was taught by Chaytor D. Mason, USC Professor of Aviation Psychology. He told us about an Air Force T-38 crash that appeared to have been caused by a lieutenant general attempting and failing to fly an aileron roll right after takeoff, which would have made it just about a good-looking corpse taking his own life and of the instructor pilot in the back seat assigned to keep the general safe. What really happened took an aviation psychologist to figure out.

The lieutenant general was the commander of the Air Training Command (ATC), the organization charged with training Air Force personnel. He had just completed a week-long tour of his command, flying the T-38 to each base, accompanied by his aide, a T-38 Instructor Pilot (IP). His last flight as the ATC commander was from his headquarters base, Randolph AFB, Texas, to his new assignment at Scott AFB, IL, where he was to take over the Military Airlift Command (MAC) and receive a promotion to his fourth star. On the morning of the accident, the flight line was filled with the perfect eyewitnesses, instructor pilots current and qualified in the accident aircraft. What they saw was the aircraft rotating, flying an aileron roll, and crashing. But if that were the case, the crash site should have been very large as the aircraft hit still going forward at a great speed. But the crash site was very compact, as if the aircraft flew in at a steep pitch angle. The expert eyewitness accounts were not supported by the crash site evidence.

Professor Mason was called to look at the mystery from a human factors angle. After interviewing the eyewitnesses he determined that the night before the general was heard at the bar berating the IP for not knowing how to extract the maximum performance from the airplane. Piecing together these statements he also figured out that the general had been rotating below the recommended speed and that on the previous day, the IP nudged the stick forward after rotation and the general exploded in anger over this. He then told his barroom audience that he would put on a show of how to max perform the aircraft the next day, explaining why there were so many witnesses. But what about the aileron roll?

Mason figured out that the witnesses had a clear view of the takeoff through the crash except for a portion blocked by a tall building and later by the local terrain. They saw the aircraft pitch up and roll about 90 degrees before their view was obstructed. After the obstruction, they saw the airplane continue the roll, disappear below their horizon, and then the fireball of the explosion. He believes what really happened was the general rotated too early, the aircraft rocked to one side in a stall, then when out of view, reversed the roll and rocked to the other side until reversing the roll again. At that point the witnesses regained view of the aircraft.

Aileron roll or stall? Either way, the lieutenant general was a pilot looking to die young and leave a good-looking corpse.

For more about this crash: T-38 70-1956

3

My rock star example

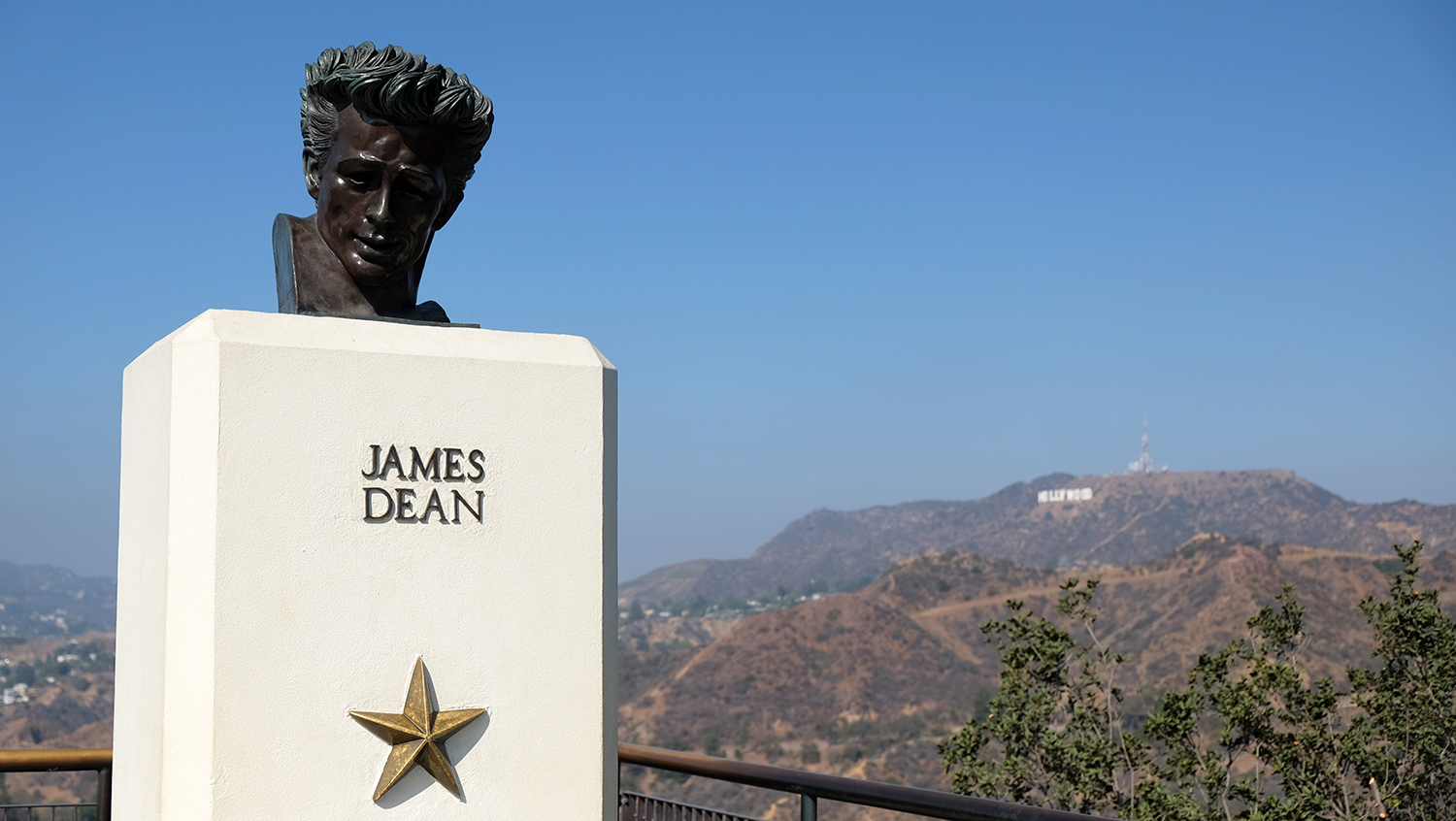

A “well-known” rock band commissioned my Gulfstream GV to fly them from London to “Hollywood” and two things happened to sour our passengers on us, both related to my use of quotes in this sentence. The first thing: I didn’t recognize any of them. I greeted them politely but didn’t say anything other than hello or hi. Our flight attendant said the passengers thought I came off as cold. The second thing: I couldn’t fly them to Hollywood. When we accepted the charter, we indicated we would be going to Bob Hope / Burbank. But before we took off, Burbank’s longer runway was NOTAM’d closed and the shorter runway was NOTAM’d even shorter at 4,500’ which was 500’ shorter than we needed by the book. Can a GV land on 4,500’ of runway? Sure. But Los Angeles International was close by and I opted for that instead.

The passengers spent the long flight complaining about everything, including the choice of LAX for our destination. At one point the flight attendant said the lead passenger, who I guess was the lead singer of the band, said they would never use us again. It wasn’t until we landed in Los Angeles that they realized it was a nonstop flight, something they hadn’t done before. All of a sudden they wanted a group photo in front of the airplane and a business card so they could charter us for their next Europe trip. (We never heard from them again.)

4

A few more rock star examples

A friend of mine flew for another rock band that must have been more famous because I recognize the band’s name and might recognize the lead singer if I were to see him. They started with a small twin-engine prop and upgraded airplanes as they grew more famous. By the time they were flying jets, whatever rulebook they had was thrown out the window. When they started flying charters with untrained pilots without type rating, my friend quit and let the local FSDO know they had a problem. Of course, nothing happened. They flew their jet through some trees on an approach, cleaned off the branches and continued operating the aircraft until the owner noticed. After a landing that was hard enough to bend a tip tank, the FAA finally got involved but the inspector agreed to look the other way if they would hire him as a contract pilot and allow him to attend a concert. After one flight the inspector was so scared that he took an airline home and never flew with them again. Once the band started falling in the charts the airplanes went away.

A YouTuber pilot with minimal qualifications got hired as a Gulfstream GIV pilot for another well-known rock band. He was a sea plane pilot who bought the GIV rating but had no experience flying long haul international trips. The rock band liked him so much they hired him as their full-time pilot. One of his YouTube videos shows him flying from the U.S. to Saudi Arabia in a single duty day. He bragged after the landing that he had been on duty for 26 hours.

5

A few billionaire examples

I have flown for a few billionaires over the years and whenever confronted with a request I thought unsafe, I said so and they took me at my word. But over the years I’ve heard of others who were not so fortunate.

A major football team has a few aircraft spread over several airports, two of which were in the hangar next to ours. Whenever we let it be known that we were hiring, half of the football team’s pilots sent me resumes. I asked why they wanted to leave their present gigs and got more than a few stories about how things were for our neighbors. The best summary of their flight operation came from an interview question. “If you are flying the team’s owner back home and shoot the instrument approach only to arrive at the DA with no runway in sight, what do you do?” If you say execute a missed approach the interview is over, and you are sent along your way. I never hired any of these pilots, thinking that if they were willing to do that, I couldn’t predict how they would fly for us. They had no problems flying for a future good-looking corpse. I want everyone in our operation to die of old age.

A large management company I flew for was hired to fly for the richest person in the world, at least he was back then. On his first trip from the Middle East back to the West Coast of the United States, the flight department arranged for a crew swap in Narsarsuag Airport (BGBW). The second crew was in position at Narsarsuag but the weather went below minimums. The first crew diverted to Kangerlussuag Airport (BGSF), which was more than a day’s drive away. The passenger ordered the first crew to continue the trip, another 10 hours on top of their previous 10 hours. The crew called in to say they were willing to do that. The management company said no. The passenger told the management company he would fire them if they didn’t continue the trip. The management company told the pilots they would be fired and reported if they did continue the trip. The passenger fired our management company. Our company didn’t want potential good-looking corpses as customers.

6

Surviving a flight with a future good-looking corpse

There might be a lot of examples of future good-looking corpses becoming mangled in their aluminum coffins because they pushed their pilots too hard, but the evidence trail usually goes up with the airplane. You could argue the March 29, 2001 crash of a Gulfstream GIII at Aspen was just such a case. (More about this: Gulfstream GIII N303GA) No matter which future good-looking corpse is pushing you, there are a few survival techniques to consider.

Playing the “safety card” first is not always a good idea. In the case of me telling the general I didn’t want to go swimming, that could have been interpreted as me telling the general what he wanted to do was so unsafe as to be stupid, or me saying to him, “you are stupid.” All of that might be true, but it may have been better to attack it from another angle.

Explain the physics

The future good-looking corpse may not understand that the aircraft is the limiting factor and that force of will isn’t going to change that. I could have told the general that our aircraft was very heavy due to all the cargo on board, we took off with all the gas we could load, and that our range was critical even at the lower speed we had planned. We also want to fly faster, but we can’t.

Ask for advice.

Pose the problem to the future good-looking corpse and ask for their wise counsel. “The performance charts are telling me we don’t have the range. Do you have a technique for reducing our fuel consumption?”

Offer alternatives

My flight department goes to Teterboro Airport, NJ quite often because it is the closest airport to many of our company’s New York City customers. But the weather and traffic flow often makes Teterboro our least favorite options as pilots. We will offer the surrounding airports as better alternatives, given air traffic delays into and out of Teterboro, as well as the ground traffic into the city.

Preplan alternatives

A friend of mine often flies from Eastern China to Western Europe, a long flight where air traffic control and the weather can conspire to erode any fuel margins. His answer has been to preplan all the details necessary for en route fuel stops, including landing permits even though his Plan A doesn’t require them. This way he can minimize that added travel time when Plan B becomes necessary.

Declare your red line

What of the instructor pilot flying with the general wanting to become a good-looking corpse before his time? As harsh as it sounds, saying no to your boss and getting fired is better than saying yes and getting killed. As professional pilots we need to be always on the lookout for alternative career choices. That will make saying no a more palatable option than when yes is your only option. I have been faced with a few of what we would call “career defining moments,” both as an Air Force pilot and as a civilian. More often than not, the situation resolved itself in my favor. But even when it didn’t, I found another job and am here to write about it.