They say "experience is the best teacher," but what if you don't have a lot of personal experience that is relevant? We often resign ourselves to the situation, knowing that we have to "pay our dues" along the way to growing that experience. I don't think that is necessarily true. They also say you should learn from your mistakes. Wouldn't it be better to learn from someone else's mistakes?

— James Albright

Updated:

2021-12-15

Similarly, I think we can learn from the experiences of others. You just have to pay attention.

1

Learning from SOPs, manuals, and case studies

Lessons from the experiences of others

Your aircraft manuals, company Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs), government regulations, and all those other things stuffed away into your bookbag and iPad, all those things reflect the learned experiences from those who came before you.

We were told in some of our Air Force aircraft that, "the flight manual is written in blood." A bit over the top? Perhaps. But when I flew the T-38 in 1979, the Air Force crashed 4 of them. And that was a good year, the average loss rate was 7 per year up to that point. Even in the relatively subdued world of the KC-135A tanker, we were crashing at a rate of 2.5 per year. So, written in our manuals, were the lessons learned from all those lost lives and aircraft. If you want to learn from the experiences of others, study your aircraft manuals, SOPs, and just about everything else you can get your hands on dealing with airplanes.

There are no better lessons about how to avoid aircraft accidents than reports of aircraft accidents. Seek out those that deal with your aircraft, the places you fly, or any that deal with your types of operations.

For example . . .

On Sunday 31 May 2009, an Air France Airbus A330-203 departed Rio de Janeiro Galeão bound for Paris Charles de Gaulle. It was an overnight flight with a cockpit crew of three: a captain and two first officers. The captain was in back during an authorized rest break when ice crystals caused the airspeed indications to momentarily disappear from both Primary Flight Displays (PFDs). The autopilot disengaged and the flight director cross bars disappeared as a result. The aircraft was at 35,000 feet, Mach 0.82, and the pitch was 2.5 degrees nose up. The first officer, who was the Pilot Flying (PF), instinctively pulled back on the stick, pitching up to as high as 11 degrees, despite the other pilot's admonitions to lower the nose. 29 seconds after the loss of both airspeed systems, one came back. The PF relaxed back pressure, allowing the nose to come down to 6 degrees momentarily, then right back up to 10 degrees. Then the second airspeed system came back, allowing the stall warning system to sound. The PF pulled back on the stick further to 16 degrees, even as the other pilot pushed forward. The captain returned to the cockpit and witnessed the confusion but was unable to figure it out. The aircraft was dropping 11,000 feet per minute when it impacted the ocean, less than 5 minutes after the initial loss of airspeed information.

For more about this accident: Case Study: Air France 447.

When the accident report came out, the industry seemed to focus on the design of the aircraft's flight control system, which allowed each pilot to command an opposite pitch movement without the other pilot noticing. That isn't what caught my attention. I was more interested in the fact all three pilots couldn't understand (or believe) their aircraft was in a stall at 35,000 feet with the nose pitched 15 degrees up. I thought about it for a while and realized that just about every aircraft I have ever flown, cruises at altitude at nearly full thrust and just a few degrees nose up. Had these pilots realized this, they could have saved themselves. Had the PF realized that anything more than a few degrees nose up at cruise will result in a loss of airspeed, the stall would never have happened in the first place.

Applying those lessons

On September 10, 2002, I was flying this aircraft from Houston Intercontinental Airport, in Texas. It is a Challenger 604 and this was to be my last trip with the company, Compaq Computer, before they were sold to Hewlett Packard. Most of our pilots had already found other jobs and I was paired with a contract copilot I had never flown with before. As we taxied out our primary Air Data Computer failed but our manuals said we could continue provided the autopilot was engaged prior to 200 knots. So we pressed on. I engaged the autopilot as soon as the flaps were up and it initiated a turn to the left. I smashed the autopilot disengage button and nothing happened. I asked the copilot to try his. He was frozen with a zombie-like stare, so I reached over and hit the autopilot enable bar, on his side of the cockpit, and that worked.

I leveled the wings and considered our broken jet. My airspeed indicator said we were in a stall, his indicator said we were doing 280 knots, and the standby was somewhere around 200 knots. I didn't trust the standby system because it had been giving us problems for months. It would work fine at first, but sometime after takeoff it produced nonsense. The week previous to this flight, our mechanics drained a cup of water from the standby system's static lines and pronounced it fixed. In my view, all three systems were suspect. I tapped the copilot on the shoulder and asked if he was okay. "Of course I am," he said, "why are you asking?" I asked him to declare an emergency and get us back for a landing. All was going well until I asked for the landing gear. "We're too fast," he said. His indicator showed us still doing 280 knots. Mine still showed us in a stall. "Does the aircraft sound like it's going that fast? Our pitch is where it needs to be and so is the thrust." He extended the gear and we landed.

Did I land on speed? Don't know. But we were in the ballpark. We didn't have autothrottles in that airplane and that was probably a good thing. I was used to setting EPR for all conditions of flight. Every aircraft I've flown since, takes care of the thrust for me. I have to remind myself to pay more attention to how much thrust it takes to fly the aircraft under every possible condition. But on that day in 2002, knowing the correct pitch and thrust setting after takeoff and for landing, made a non-routine situation almost routine.

2

Learning from chair flying

Lessons from the experiences of others

One of the challenges of learning in any complex environment is that you don't always know the right questions to ask. In short, you don't know what you don't know. Aviation is a poor place to "learn as you go," since mistakes can end up being fatal. Aircraft simulators are an excellent way of doing a "test run" of things you are just learning, so that you can bring yourself up to a minimum acceptable performance level before it really counts. But you don't need a simulator to simulate.

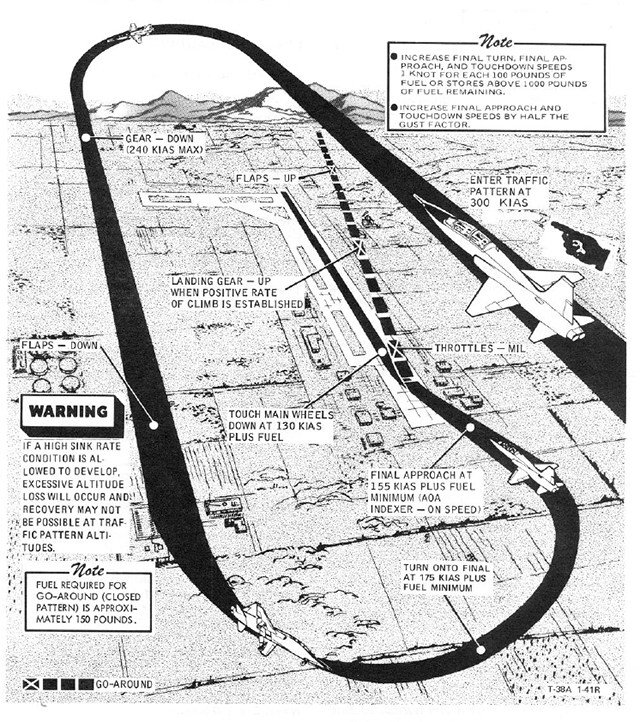

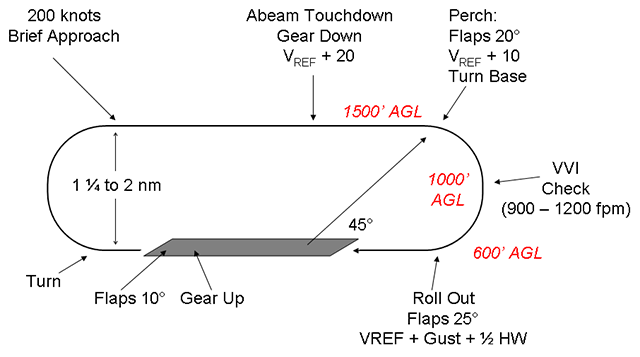

If you want to allow lots of takeoffs and landings in a minimum amount of time with a minimum amount of air traffic control, there is no better way than to have pilots well schooled in the art of the overhead pattern. We learned this early in the Air Force and the procedure didn't seem too bad in the slow moving T-37, which started the procedure at 200 knots and ended up landing just over 100 knots. Flying an overhead pattern in the much faster T-38 required much more focus.

You begin the maneuver at 300 knots, 1,000 feet above the runway. Next comes a level 2-G turn at 60° of bank to reverse direction and bleed off the speed. Then comes configuring the aircraft, timing the final turn, turning while allowing the nose to fall, and then rolling out on final. All of this happens while ensuring proper displacement with the runway and other aircraft. We were told to "chair fly" the maneuver from the safety and comfort of our dining room tables, over and over again, so that the procedure became almost automatic in the airplane. We were encouraged to place our hands on an imaginary stick and throttles to develop some muscle memory. I found it helpful to draw out the procedure, even many years into the future flying aircraft that were not so fast:

More about this: Stories: 1979 - Final Turn.

Applying those lessons

I tend to diagram these procedures just to keep the process clear in my head. I might not ever look at the diagram again, but the act of drawing it helps me to remember it. This is a mental way to chair fly for me and it has always proved useful. As I am writing this, I have been trained to use my aircraft's Enhanced Vision System (EVS) all the way to touchdown. That means I can land the aircraft without actually seeing the runway using what the FAA calls "natural vision." There are visibility minimums, of a sort. But for the most part, EVS is one step removed from magic. I have diagrammed it and will use that diagram until the procedure becomes automatic.

Landing an airplane with only an infrared camera seen through an EVS will be a new experience and I am sure it will be an uncomfortable one for a while. Despite the many times I've done this in the simulator, in real life it will be anything but routine at first. Chair flying the procedure will help speed that process along.

3

Learning from war stories

Lessons from the experiences of others

The classic fighter pilot war story begins, "There I was, flat on my back, out of airspeed and out of ideas." Our hero is in the dog fight of his life and his adversary, somehow, got the better of him. There he is, inverted, approaching a stall, and his enemy is zooming up to get him, just waiting for his gun sight to center. "I realized too late that I should never have started a fight at such a low energy state. I should have waited." If our hero survives, the story has one of two possible endings: derring-do or dumb luck.

If the former, it could end with, "I was about to stall and maybe even spin. How did that dumb sum-beech get the better of me? He must have anticipated my every move! That's when it came to me, I'll do the last thing he suspects. I kick in full rudder and the aircraft drops out of the sky, and away from Charlie's pipper. I wave goodbye. Pretty soon it dawns on me that I am in a spin, but I know how to get out of that. I bring the airplane home a little bent. But at least I brought it home!"

If the latter, it could end with, "I am saying my last prayers, hoping the end will be merciful. But just as I say 'amen' the aircraft stalls and heads downhill, fast. As I gather my bearings, nose pointed to the earth, as if by divine providence, there sits Charlie, right in my sights. I guess he stalled too. It seemed only humane to put him out of his misery so I sent a missile right down his tailpipe."

Either way, the story accomplishes three things. First, it tells the audience what happened. Second, it gives the lessons learned. Finally, it entertains.

Why not just state the facts? A well told war story will be remembered and attaches an emotional aspect to the lessons. You might think a war story told at the bar is just one pilot bragging about his or her latests exploits. That might be true. But it might be just the war story you need to learn something that could someday save your life.

Applying those lessons

Can a war story save your life even if you aren't in the middle of a war? Absolutely. My favorite comes from Retired Navy Captain and space shuttle commander Jim Wetherbee. See: Teaching through story telling. But even when the lessons are less than life and death, they can be invaluable.

When I showed up at Andrews Air Force Base, they were just completing the transition from the Lockheed VC-140 Jetstar to the Gulfstream III, what the Air Force branded the C-20. Many in the squadron had Jetstar experience and would tell story after story about (a) what a good airplane it was, and (b) how you really had to know your stuff to fly it. Case in point: oceanic crossings.

"There I was," the story begins, "cruising along at 38,000 feet without a care in the world, when we ran out of thrust and fell out of the sky." After they got our attention, they would explain that while cruising along at 34,000 feet over Newfoundland, the Outside Air Temperature (OAT) would be at or colder than standard (-54°C) and they had enough left over thrust to climb to a more fuel efficient altitude. So they would climb. But soon after coasting out over the water, the OAT would rise 10 or 15 degrees and without any excess thrust, they would slow dangerously close to stall speed. They had no choice but to beg for a lower altitude. Even though we were flying a more capable Gulfstream, we all took heed that the OAT is warmer over water, even in the winter. (Especially in the winter!)

Fast forward ten years and I was a civilian instructing pilots brand new to oceanic operations. Despite being taught about the problem of running out of thrust over the warmer ocean, new pilots would invariably look at the surplus thrust while flying over Newfoundland heading east or Ireland heading west, and suggest we should climb a few thousand feet for the crossing. "Save us some gas," they would add, helpfully. I would counsel patience. We would invariably go "feet wet" and watch the OAT rise with our thrust. More often than not, we ended up with just enough thrust to maintain our lower altitude. "How did you know that?" they would ask. My answer always started with, "There I was . . ."

4

Learning from experience you don't have

Experience can be a valuable tool in your arsenal, no doubt about it. But just because you didn't personally experience the lesson doesn't mean you can't learn from it. You should study your SOPs, manuals, and any pertinent accident case studies. You should chair fly procedures you are unsure of to see if any questions come up that can be answered before you fly the procedure in a real airplane. And you should listen to and tell war stories that can help others as well as you. You will soon find that others will credit you for wisdom beyond your years.