Back when flying was simpler because there were fewer airplanes and much less technology, you could get by with a good knowledge of the FARs — the Federal Aviation Regulations — and perhaps a good understanding of what used to be called the Airman's Information Manual, or AIM. But commercial operators needed something more, and we got "OpSpecs" as a result. Before too long, however, even non-commercial operators needed something from the FAA to be authorized to fly in some airspace or do some procedures. So these days, you need to be well versed about Letters of Authorization (LOAs).

— James Albright

Updated:

2023-03-30

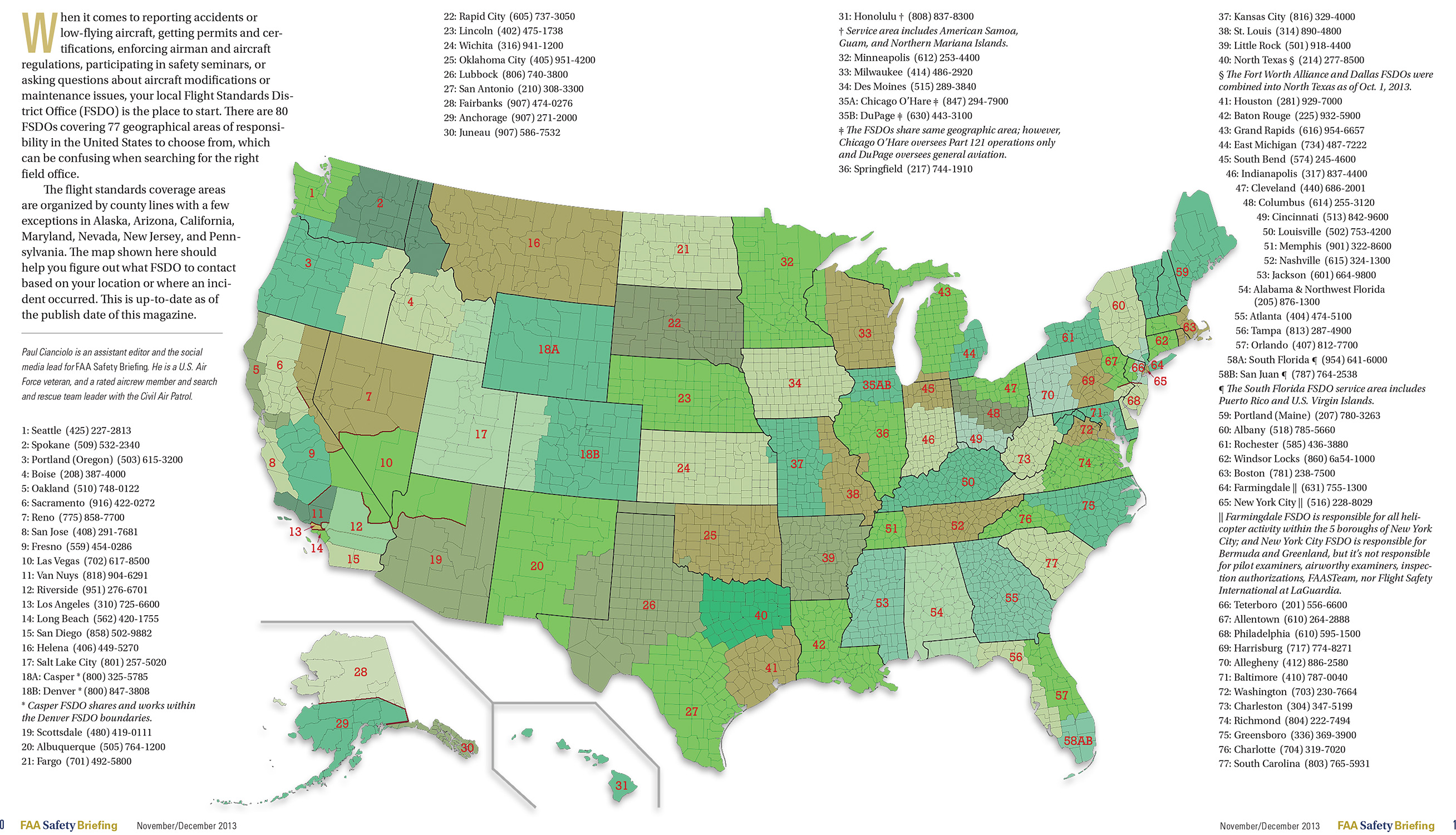

There is no easy crash course called LOAs 101. But even if there was, it would be out of date because things are changing so quickly. I applied for my first LOA in the year 2000, as part of my first civilian flying job, and have repeated the process every few years until my last set, last year. If your aircraft isn't new off the factory floor, the process of application is easier, but the process of getting through the FAA is still heavily dependent on the generosity of your local Flight Standards District Office (FSDO). If, however, you are applying for a brand new aircraft, your processes are very much improved.

1 — The need for OpSpecs and LOAs

3 — Approval process (not streamlined)

4 — Improvement: Standard templates

1

The need for OpSpecs and LOAs

Up until 2022, you could find just about everything you needed when looking for information about each Op Spec, LOA, or other authorization in a very long document called "Order 8900.1 - Flight Standards Information Management System." That has been replaced by a three-page document that tells you the old treasure trove of information is gone. It is unclear what has happened to that information and where to look for what you need, but more on that later. The since canceled order does provide a history lesson . . .

History of OpSpecs

The early U.S. Civil Air Regulations (CAR) did not provide for OpSpecs. A valid certificate or temporary permit was the principal federal authorization for conducting any air commerce operations. In addition to the certificate or permit, each operator had to possess valid competency letters, or temporary letters, issued by the Secretary of Commerce. These letters, which contained information relating to the operator's services, routes, aircraft, maintenance, airmen, and weather procedures, were appended to and considered part of the operating certificate. For example, CAR part 61.01 required each air carrier to operate in compliance with the terms, conditions, specifications, limitations, or other provisions of its certificate or temporary permit which included the competency or temporary letters. In 1953, the Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB) revised the CARs to require that each operator apply for OpSpecs at the time of application for an air carrier certificate. Air carriers that existed at that time were issued OpSpecs to be used instead of the competency or temporary letters. These revised rules specified that the OpSpecs were not part of an air carrier certificate.

Source: FAA Order 8900.1 (Canceled), Vol. 3, Ch. 18, §1., ¶3-676

Before OpSpecs commercial operators needed authorizations but there wasn't a standardized way of ensuring the authorizations were valid, current, or even applicable.

Conceptual Need for OpSpecs

Within the air transportation industry there is a need to establish and administer safety standards to accommodate many variables. These variables include: a wide range of aircraft, varied operator capabilities, the various situations requiring different types of air transportation, and the continual, rapid changes in aviation technology. It is impractical to address these variables through the promulgation of safety regulations for each and every type of air transport situation and the varying degrees of operator capabilities. Also, it is impractical to address the rapidly changing aviation technology and environment through the regulatory process. Safety regulations would be extremely complex and unwieldy if all possible variations and situations were addressed by regulation. Instead, the safety standards established by regulation should usually have a broad application that allows varying acceptable methods of compliance. The OpSpecs provide an effective method for establishing safety standards that address a wide range of variables. In addition, OpSpecs can be adapted to a specific certificate holder or operator's class and size of aircraft and type and kinds of operations. OpSpecs can be tailored to suit an individual certificate holder or operator's needs. Only those authorizations, limitations, standards, and procedures that are applicable to a certificate holder or operator need to be included.

Source: FAA Order 8900.1 (Canceled), Vol. 3, Ch. 18, §1., ¶3-678

We need operator-specific authorizations, OpSpecs, MSpecs, or LOAs, to tailor broad regulations to individual aircraft types, operators, locations, and other unique situations. It is impractical to modify regulations to adapt to advances in technology and other changes, and it would be difficult to do this in a timely manner. In theory, an OpSpec, MSpec, or LOA can meet all these needs.

2

The broken process

Arts and crafts projects

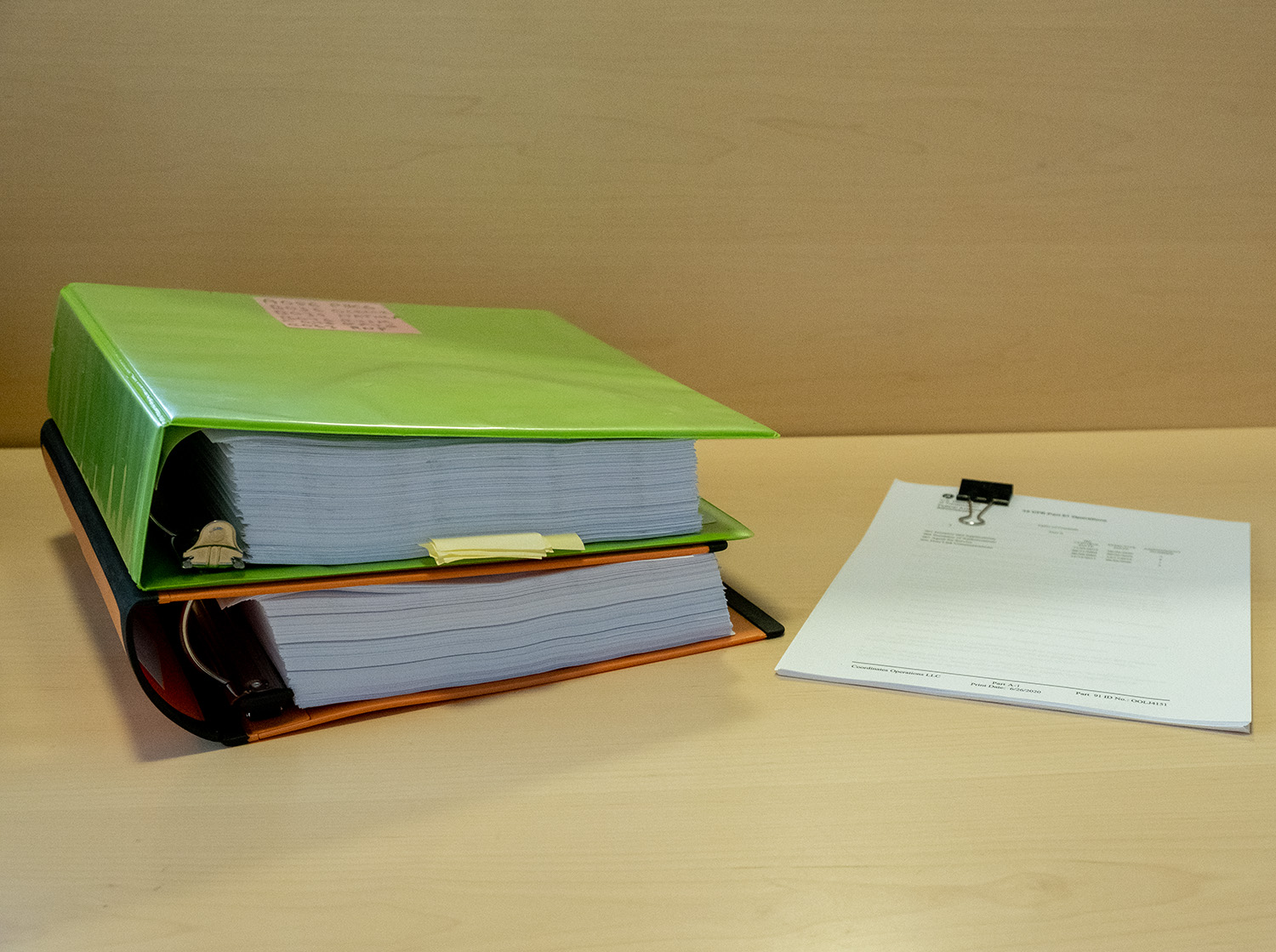

Many people who have survived an initial LOA application for an aircraft flying internationally knew the process as a huge "arts and craft" project. You had to cut and paste documents from a wide variety of sources. The first time I had to do this for a new aircraft was in 2009 and the finished product had to be submitted in paper form, more than a thousand pages worth. So we got a lot of use out of a copy machine. The last time I did this for a brand new aircraft was in 2019. That submission had to be in electronic form, so the copy machine got a rest, but we needed a high speed scanner and ended up doing a lot of digital cutting and pasting. That meant using Adobe Professional for the electronic arts and craft project.

What made the process so infuriating was that a vast majority of the documents were already FAA approved. Our 2019 application, for example, had 465 pages from various manuals from our aircraft manufacturer, all of which had already been FAA approved. Incredibly, our local FSDO contested many of these. Another issue is the duplication of various documents through the six LOA applications submitted at the same time. We had to submit a sample flight plan for the A056, B036, and B039 applications. Because these were farmed out to various inspectors who all got to their part of the puzzle at different times, and because the flight plan codes were changing, we had the identical flight plan approved for some LOAs and disapproved for others.

"They" don't know as much as "we"

Another problem that slows the process down is the absence of relevant expertise at your local FSDO. Many years ago, while trying to get a modified Gulfstream G450 PBCS qualified, we spent more than a month trying to get the FDSO to even assign an inspector to our case. We finally got a PAI tasked and then we spent a few weeks answering what can only be called dumb questions. "Tell me, what does datalink have to do with CPDLC?" This continued until the inspector gave up and sent our application to Washington, D.C. where it landed on the desk of the subject matter expert. She eventually approved the application without comment. Years later she retired and started a company that promised to smooth the LOA process for us, touting her expertise and contacts within the FAA. Our airport users' group invited her to speak and it became apparent she didn't have a clue about any technology that involved a microprocessor. Needless to say, her company didn't last long.

The lack of standardization amongst the FSDOs

There are 77 Flight Standards District Offices (FSDOs) in the United States, each of them operated independently and many of those by managers who refuse to listen to the hierarchy. A few years ago, I shared the stage at a safety stand down with an FAA inspector from the D.C. office who offered to help when I complained about a stalled LOA in ourFSDO. He sent an email to the FSDO, with a copy to me, asking for the status. What he got in reply was a scathing rebuke from the head of the FSDO, asking how he dared mettle with something that was none of his business. The D.C. inspector backed down without a fight. Three months later the local FSDO said my application had made it to the top of the list, but they had lost it and needed me to resend it. This was for a brand new airplane with an established flight department using top of the line maintenance and training. Meanwhile, I had friends using two other FSDOs receiving their LOAs for the same aircraft type, both in under five weeks.

I've heard similar stories from all over the country and have come to the conclusion that if you are in one of those troublesome FSDOs, you should take your business elsewhere.

The bureaucracy exists to perpetuate the bureaucracy

After my first run in at our troublesome FSDO, I asked our POI why he had to read every page of the AFM extract he had asked for, when the manual itself had already passed FAA scrutiny in Savannah. He told me, "I don't know anyone in Savannah and it's my signature on your LOA. So I need to do my own work."

3

Approval Process (not streamlined)

How it should work and how it does work at some (most?) FSDOs

In 2006 I was flying a Gulfstream GV under 14 CFR 135 using Operations Specifications issued by a very good FSDO. We thought it would be prudent to have a complete set of 14 CFR 91 Letters of Authorization. After a simple phone call to our Principal Operations Inspector, we had the necessary templates which took all of a few days to complete. Less than a week after submission, we had our LOAs. That's how it works in much of the country.

Rogue FSDOs: difficult by design?

Three years later, flying for a Part 91 operation using a management company, I was tasked with taking our flight operation "in house," meaning on our own without the management company. I called the nearest FSDO and was given a few photocopied instructions and assigned a principal inspector. After my arts and craft project, I called our inspector and offered to drop off a USB stick with all 900 pages of our application. He told me they didn't do things like that, I would have to print them out and mail them in. So I did that. Then began the six months of hide and seek.

I would call for the status of our application and was told the inspector wasn't in and there was no one else I could talk to. I showed up at the FSDO and was told the inspector was too busy to see me. I sat down in the waiting room and said I would wait. After two hours the receptionist asked me how long I was going to wait. I told her until the inspector walked out the door. He managed to see me about ten minutes later, but claimed there was no movement on our package. A week later he called and said I would have to send someone over for a "table top" so they could evaluate if we knew what we were doing when it came to oceanic operations. I told him, "I'll be right over." "Don't you want some time to prepare?" "I'm ready now." "We'll get back to you." Of course they didn't. This was in 2009 when RVSM rules applied in the U.S. and that meant our company had just spent tens of millions of dollars on an airplane they couldn't fly above 27,000 feet or outside the U.S. Our CEO called a friend in D.C. Two days later the FSDO called, asking me to come to sign our newly approved LOAs. The process took seven months.

Ten years later I repeated the process, aided by changes in technology and previous battle scars. I managed to get templates for all six of the LOAs we would be needing. Our FSDO assigned an inspector who I knew and who promised quick action. He said I could speed things along if I paid for and attended classes on a new FAA portal called the Web-based Operations Safety System (WebOPSS), so I did that and uploaded all our applications. Our newly assigned inspector said all was received, now we just had to wait for someone at the FSDO to get our case. When? Don't know. I called once a month for the next six months, eventually finding out that our FSDO would no longer allow us small Part 91 operators to have a single point of contact. Our case would simply wait until the next available inspector got to us. Then after six months, we finally got the call. The inspector asked me to email everything. "What about WebOPSS?" I asked. "Ah, I don't use that. Just email them." A month later I found out our case was farmed out to another FSDO, since our FSDO didn't have the necessary expertise.

While we were playing that game, I heard from flight departments all over the country flying the same aircraft and logging the same training. It seems just about every FSDO in the country except two or three were issuing these LOAs in weeks, not months.

Some advice

- Complete the application, have someone QC it

- Find an ally at the FSDO

- Consider "FSDO shopping"

- Keep records

- Pull strings

Most of the LOAs now have very good application guides, replacing a hodgepodge of templates, job aids, and other guides that were not consistent or straightforward. But you still need to make sure your application doesn't have any errors. Check, and double check everything to avoid the initial "kick back." If you give the inspector any reason at all to reject the application, at some FSDOs, it seems you go to the bottom of the pile for your next attempts.

If you know someone at the FSDO, strike up a friendly conversation and ask for advice on how best to submit the application and to whom. If the person handling your application drops the ball, you can circle back to your contact to get things moving again.

If your FSDO has a track record for poor customer service — remember that you are the customer — ask around and see if you have a better FSDO nearby. Nothing requires you use the nearest FSDO.

Dedicate a calendar or other record keeping device and log everything that you do with dates and times. I managed to get things going a few times by sending in a page of actions on my part and inaction on the FSDO's part. If your FSDO places responsibility for each flight department in a single inspector, that inspector will take ownership of how you are treated. If, on the other hand, the FSDO has the "first available inspector" mentality, you are more likely to be forgotten. A record of how forgotten you have been may shame them into doing their jobs.

If you find yourself in the months without LOAs situation, consider calling the head of the FSDO directly. If that doesn't work, have someone at your company contact the head of the FSDO with a specific request. After we had our brand new Gulfstream GVII for two months without LOAs, I contacted the head of the FSDO and said that without our MEL LOA (D195) we couldn't use our airplane on trips because if we had a minor maintenance issue on the road, we would be forced to get a ferry permit and send the passengers home on the airlines. I hinted that our CEO was furious and wanted to call in a few favors with the White House. We had our D195 a few days later.

4

Improvement: Standard templates

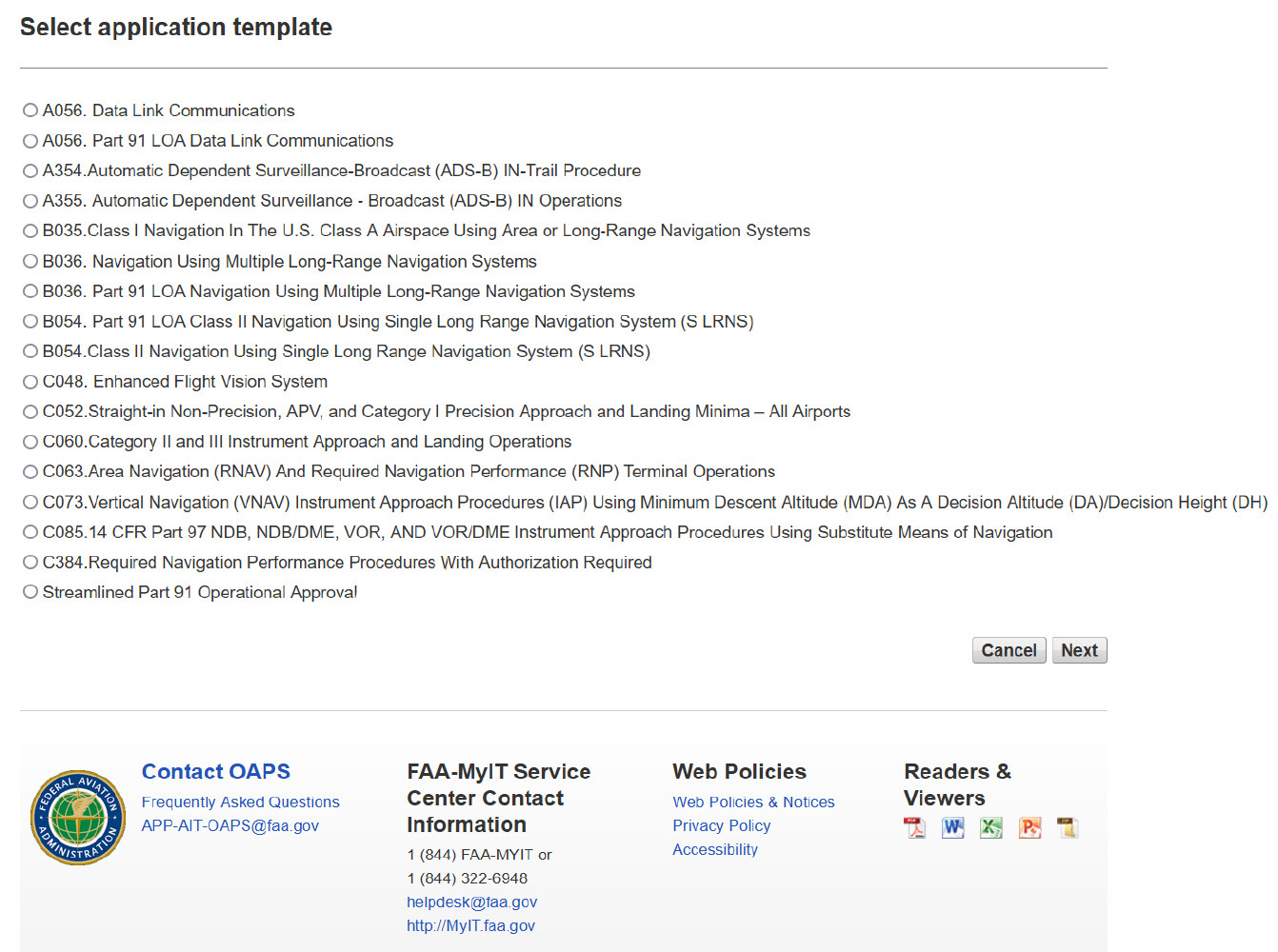

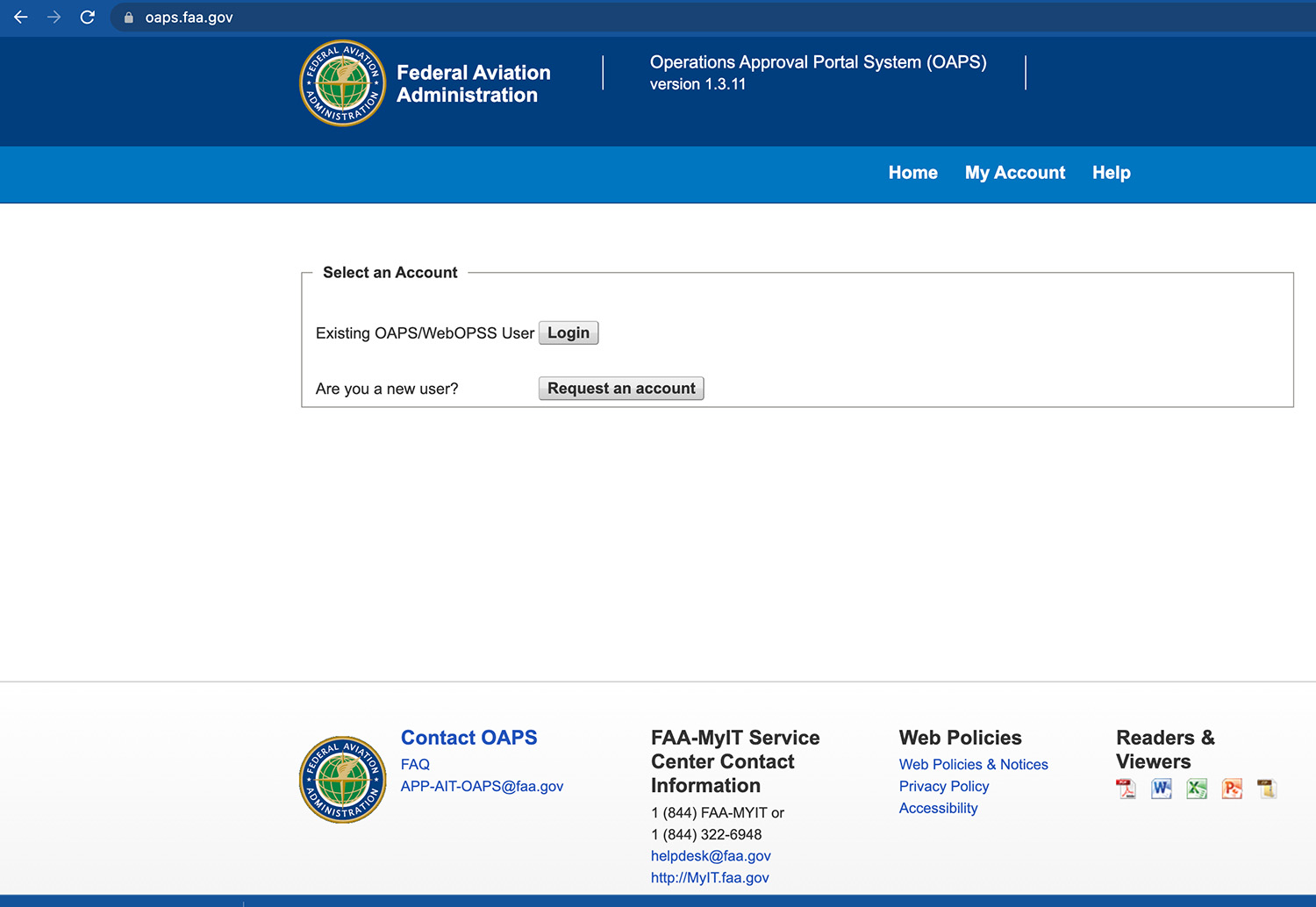

Even if you are dealing with a competent FSDO, you still have to prepare your applications. There is good news on this front. We now have standardized applications for the "top ten" LOAs with more to come, all available in one spot. You will need to use the "Operational Approval Portal System" (OAPS) to download the guides. You can request an OAPS account at https://oaps.faa.gov/.

Each application guide is a PDF file with "fill in the blank" spots for you to enter your information and instructions on how to add any needed attachments. The "arts and craft" project continues, but now it is more of an electronic cut and paste. I recommend you become familiar with and use Adobe Acrobat Professional to make the process easier.

Note: there are a lot of out-of-date application guides, job aids, and templates "out there" which will not fare well with the process. So make sure you get the correct version at OAPS. There are also a lot of links, including in the several FAA "Resource Guides," that lead you to a link on the FAA website that lead you to a dead end. Just because you've seen an faa.gov link in the past don't bank on it being correct. The right answer is OAPS. Download your guides a week or so before you think you need them because the entire faa.gov website goes down whenever there is a threat to their paychecks via a government budget "shutdown."

5

A streamlined process

The complaint from new aircraft buyers

Whenever the subject comes up from a large audience to someone from the FAA, you are sure to hear this complaint: "We bought a brand new aircraft that has already been FAA approved, we have been trained by a Part 142 school which has already been FAA approved, and all our our procedures have already been FAA approved. Why does all of this have to get approved again for us to get the authorizations to fly our aircraft as already approved?"

The Streamlined Part 91 Operational Approval Application Guide

After years of effort, the FAA has a working solution for people who have purchased a new aircraft from the manufacturer which will be operated under Part 91. This is called "Streamlined Part 91 Operational Approvals." As of February 2023, there have been 160 applications processed which required just a few pages of documentation and had a turn around time of as little as just a few days but rarely more than a few weeks. (The official goal is to have the LOA in your hands on the date of aircraft delivery, plus or minus 60 days.) Further good news: the FAA is working to expand this program for pre-owned aircraft. This single application can be used to get up to ten authorizations:

- A056: Data Link Communications

- B036: Oceanic and Remote Continental Navigation Using Multiple Long-Range Navigation Systems (M-LRNS)

- B039: Operations in North Atlantic High-Level Airspace (NAT HLA)

- B046: Operations in Reduced Vertical Separation Minimum (RVSM) Airspace

- B054: Oceanic and Remote Airspace Navigation Using a Single Long-Range Navigation System

- C048: Enhanced Flight Vision System (EFVS) Operations

- C052: Straight-In Non-Precision, Approach Procedure with Vertical Guidance (APV), and Category I Precision Approach and Landing Minima - All Airports

- C063: Area Navigation (RNAV) and Required Navigation Performance (RNP) Terminal Operations

- C073: Vertical Navigation (VNAV) Instrument Approach Procedures (IAP) Using Minimum Descent Altitude (MDA) as a Decision Altitude (DA)/Decision Height (DH)

- D195: MMEL used as an MEL

You can guide the guide here: https://www.faa.gov/sites/faa.gov/files/Part_91_Ops_Approval_App_Guide_2.2.pdf but I recommend you get it from https://oaps.faa.gov/.

Getting started

You will need to sign up for an OAPS account with your FSDO or at https://oaps.faa.gov/. You will need to have your Part 91 ID number. If you don't have one, you will need to have the FSDO assign one to you. Then you download "Streamlined Part 91 Operational Approval" template.

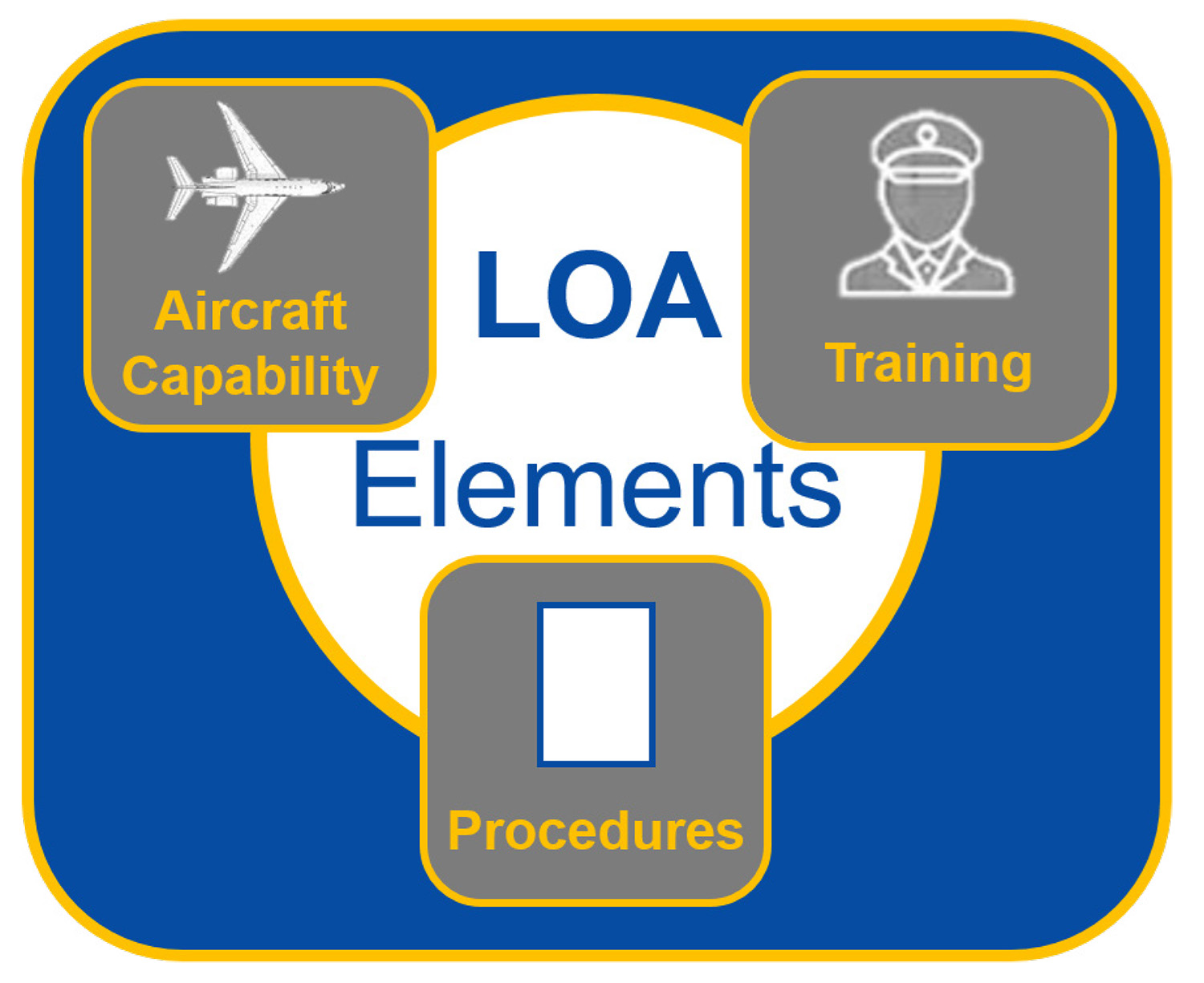

The SLOA concept

The simplified process allows you to submit three documents that prove your aircraft, training, and procedures qualify you for as many as ten LOAs. These documents are:

- Aircraft Statement of Capability (ASOC)

- Training Statement of Compliance (TSOC)

- Procedures Statement of Compliance (PSOC)

This document shows the applicable equipment installed on the aircraft and is provided by your aircraft manufacturer.

This document, or multiple documents, prove that you have been trained as required by the applicable LOAs and are provided by your training vendors.

This document, or series of documents, prove that the procedures you are using meet the standards required by the requested LOAs. Two examples would be your RVSM and oceanic procedures. The PSOCs for these would typically be provided by the vendors you used to write your manuals.

Completing the application

After you've downloaded the SLOA Application, you should fill out and review each section. Along the way you will have several steps to complete.

Request your ASOC, TSOC, and PSOC

You will typically need an ASOC from your aircraft manufacturer, one or more TSOCs from your training vendors, and one or more PSOCs from the vendors who wrote your international operations and other manuals.

Complete the sample flight plan

You will need a flight plan that is representative of what the LOAs allow you to do and the flight plan needs to reflect the aircraft covered by the LOAs. A flight plan from your service provider certainly works, provided it meets those criteria. Of special note, the flight plan must be on FAA form 7233-4, must reflect the aircraft's equipment codes in Block 10 and remarks in Block 18. The fuel categories defined in ICAO Annex 6, Part II must be used. If the application includes a request for B039, the flight plan should be for a flight across the North Atlantic. Appendix B of the application guide goes into detail about the flight plan's requirements.

PBCS Global Charter Membership (LOA A056)

If you are applying for A056, Performance-Based Communication and Surveillance (PBCS), you will need to apply for PBCS Global Charter Membership. You can join online at https://www.fans-cra.com/charter/stakeholders/. You will need to attach a screen grab proving your membership to your application.

Putting it all together

The application guide will walk you through how to attach documents and provide more information about the various parts of the application. You will submit the application through OAPS. But before you do that . . .

A few cautionary notes going forward

Chris Morris, an FAA Oceanic Specialist (AFS-10) spoke to the 2023 NBAA International Operators Conference about the Streamlined LOA (SLOA) process and noted a few challenges.

- FSDO inspectors unfamiliar with SLOA process

- Part 91 LOA applications remain lowest priority FSDO task

- Aircraft specific vs. non-specific TSOC

Source: "Regulatory Round-Up," 2023 NBAA IOC, Austin, TX

My notes about FSDO shopping apply to those first two bullets. As far as aircraft specific TSOCs, that is all on you and your training provider. For example, your datalink training must be aircraft specific, and if the TSOC doesn't reflect that, you can expect the TSOC to be rejected.

The leading cause of LOA application rejections: the sample flight plan

You may have had great success submitting your flight plans on operational flights all over the world, but worldwide air traffic control isn't as picky as your LOA inspector. A few of the errors that have tripped people up:

- Improper flight plan form

- Inaccurate aircraft configuration

- Using an outdated or prior operator flight plan

- ICAO vs FAA fuel requirements

- Flight plan codes

You must submit an FAA Form 7233-4 filled out with a flight plan that is relevant to everything you are requesting. If, for example, you are requesting B039, Operations in North Atlantic High-Level Airspace, the flight plan should cover the NAT-HLA. The computerized flight plan from your international service provider will not work unless it appears on the Form 7233-4.

The flight plan needs to be for one of the aircraft for which you are making the LOA application.

A common mistake is to simply attach a flight plan from your previous operation; that doesn't work.

The rules for alternate fuel under ICAO are different than for the FAA, and you have to use ICAO rules for your LOAs. Destination alternate fuel, for example, must include fuel to go missed approach at the destination, climb to an expected altitude, fly an expected routing, and conduct an approach and landing at the destination. (An "as the crow flies" routing will not be acceptable.) Contingency fuel seems to trip people up too. Not only must it be at least five percent of the planned trip fuel, it has to be obviously labeled, such as "CONT FUEL" to be counted as such. The same is true with final reserve fuel. Appendix B of the application guide goes into more detail.

More about this: SAFA Alternate Fuel.

Inspectors will take special scrutiny with Blocks 10 and 18 of your flight plan, so you have to get those flight plan codes right. These codes have changed frequently over the last two years, so you cannot rely on the fact your codes have worked in the past. More about this: Flight Plan.

6

A streamlined process in action

A reader shares his experience with the streamlined process, completed in early 2023. They were under time pressure and decided to use AviationManuals.com to ensure everything went smoothly. Looking at the process they followed, I am confident they could have done this "solo," but their priority was to ensure the speed of the process. More about that below.

Example flight department, using vendor assistance

Day 1 — Received ASOC from aircraft manufacturer.

Day 2 — Submitted AviationManuals' questionnaire; submitted that and aircraft's completion specification, draft MEL, and ASOC to AviationManuals.

Day 9 — Received TSOC from international procedures vendor, sent that to AviationManuals.

Day 13 — Submitted sample flight plan to AviationManuals.

Day 22 — Received completed LOA application from AviationManuals, consisting of the ASOC (5 pages), PSOC (2 pages), TSOC (5 pages), training documents, their international operations manual (378 pages), the sample flight plan (48 pages), and their PBCS charter (1 page). It was still missing their FSI training records, the airworthiness certificate, and their aircraft registration.

Day 22 — Their FSDO Inspector asked for everything they had to get ahead of the curve.

Day 25 — They received their FSI training records, airworthiness certificate and aircraft registration and submitted the rest of their LOA application.

Day 30 ‐ They received their completed LOAs.

Comments

Streamlined or not, you are at the mercy of your FSDO and it pays to have a good relationship with someone there. Even if you are a stranger to the people, the impression you make when they first set their eyes on your LOA application will make a first impression that will last. You want to make sure your initial application is as close to perfection as you can make it. That is why using a trusted vendor with a good reputation may be a sound decision. If they have a reputation for getting it right the first time and every time, an application with their name cited may get seen sooner because the inspector suspects it will be an easy and quick process.

Not all FSDOs will be familiar with the streamlined process or with OAPS. Once again, you are at their mercy and you will have to roll with the punches.

Even if you are requesting LOAs for a previously owned aircraft, the fact that the "top ten" LOAs now have standardized application guides goes a long way to improving the process.

Good luck, try not to get frustrated, and realize things are better than they were.

References

(Source material)

Advisory Circular 91-85B, Authorization of Aircraft and Operators for Flight in Reduced Vertical Separation Minimum Airspace, 1/21/19, U.S. Department of Transportation

FAA Order 8900.1 (Canceled)

An Operator's Guide for submitting a Streamlined Part 91 Operation Approval Application, Federal Aviation Administration, Version 2.2