Nobody teaches taxi technique, I suppose, because it is easy to get by with less than perfect taxi skills. It strikes me as a bit odd that most taxi accidents are at the hands of pilots with a fair bit of experience that, I think, were just lucky until the day their careers took a turn for the worse. So as obvious as these points may seem, they are worth covering.

— James Albright

Updated:

2022-08-01

- Point One: Most of the airplane is behind you — Most automobile drivers intuitively know they need to pull out of a parking space at least half the length of their car before they can turn. And yet many pilots fail to understand the need to taxi beyond the centerline of the next taxiway to make a 90° turn without ending up as an all terrain vehicle.

- Point Two: Things only get worse with speed — Not only does excess speed increase your turn radius, it makes life harder on the wheel brakes. If they get too hot, they may lose effectiveness.

- Point Three: Trying to be too smooth can turn you into a jerk — Jerk is an engineering term, it really is. But there is a way to taxi and brake smoothly without giving up precision.

- And: This problem has been with us for a very long time — You could argue that you have more situational awareness tools available to you now than ever, and yet we still seem to have taxi mishaps. I think there is a key quality missing from many pilots who have bent aircraft during the taxi phase.

1

Most of the airplane is behind you

The Problem

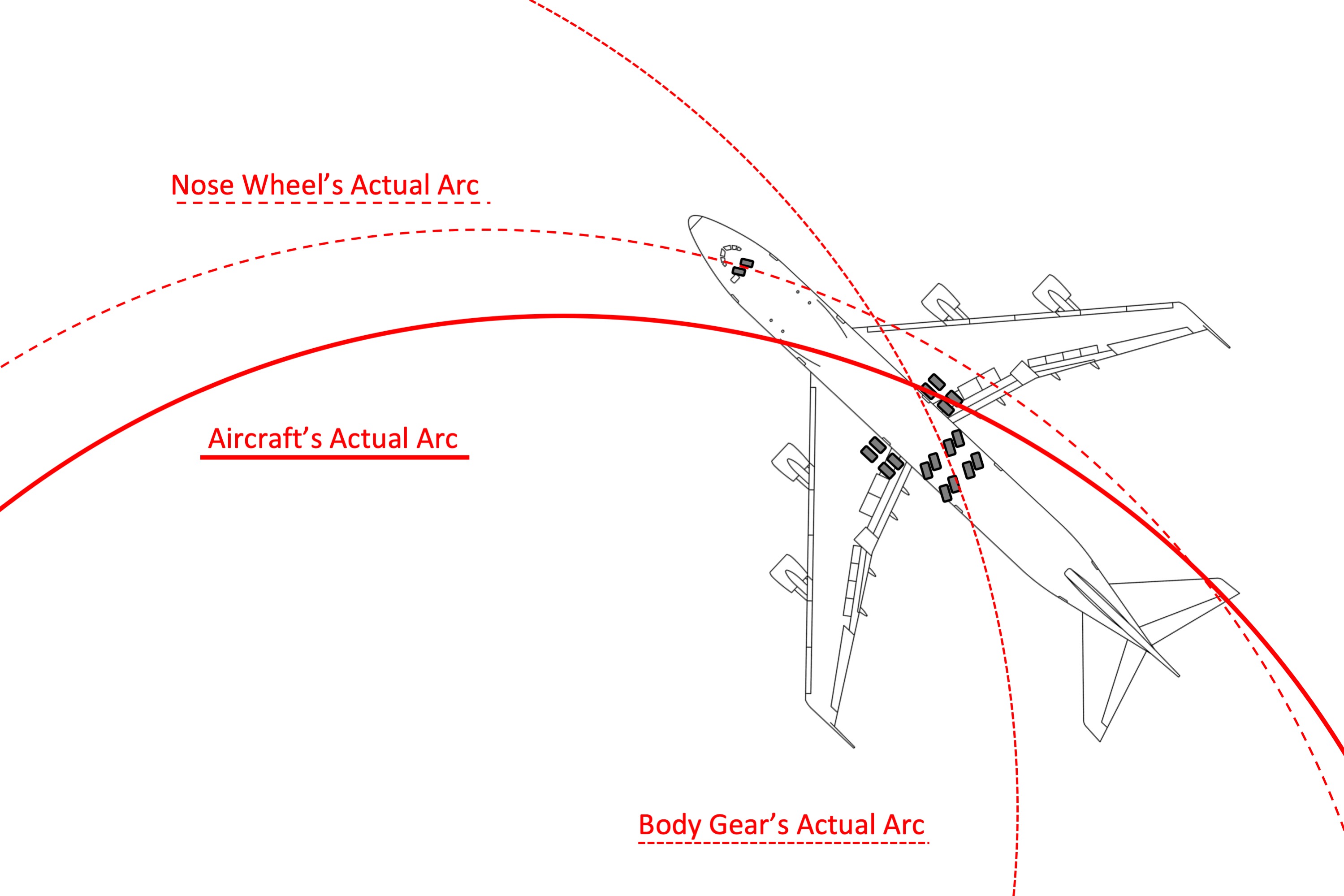

If you imagine a Boeing 747 trying to negotiate a narrow taxiway you can easily appreciate the fact the main landing gear are behind you, way behind you. The good folks from Boeing designed the airplane with two sets of main landing gear, the set furthest aft is known as the "body gear" because it was attached to the fuselage. (The forward set is called the wing gear because, well, you know.) But even still, when we taxied that airplane we couldn't start a 90° turn until we were past the centerline of the next taxiway.

What about something a bit smaller?

In a G550 the main gear are around 40 feet behind the pilot. Whenever I am in the right seat with a pilot who likes to place the nose gear precisely on the taxiway centerline, even during turns, I know I will have to be alert. And with those pilots who like huge radius turns for "passenger comfort," I am even more paranoid. With either of these pilot types I will speak up prior to a sharp turn onto a narrow taxiway, "square your turn please." I once had a pilot say, "Nah, I'm okay." I brought the airplane to a stop from the right seat.

A few years after I left the 89th Airlift Wing at Andrews Air Force Base, we had a pilot cut a corner someplace in the Midwest with the President on board. Ouch. Just imagine your aircraft on YouTube or my website. It never hurts to set the parking brake and check. I've done this many times over the years and we would have been okay all but two times. The first time we were headed for the ditch, the second time a wing tip was headed for a fence. Those two times made all the other times worth the price of the false alarms.

The Solution

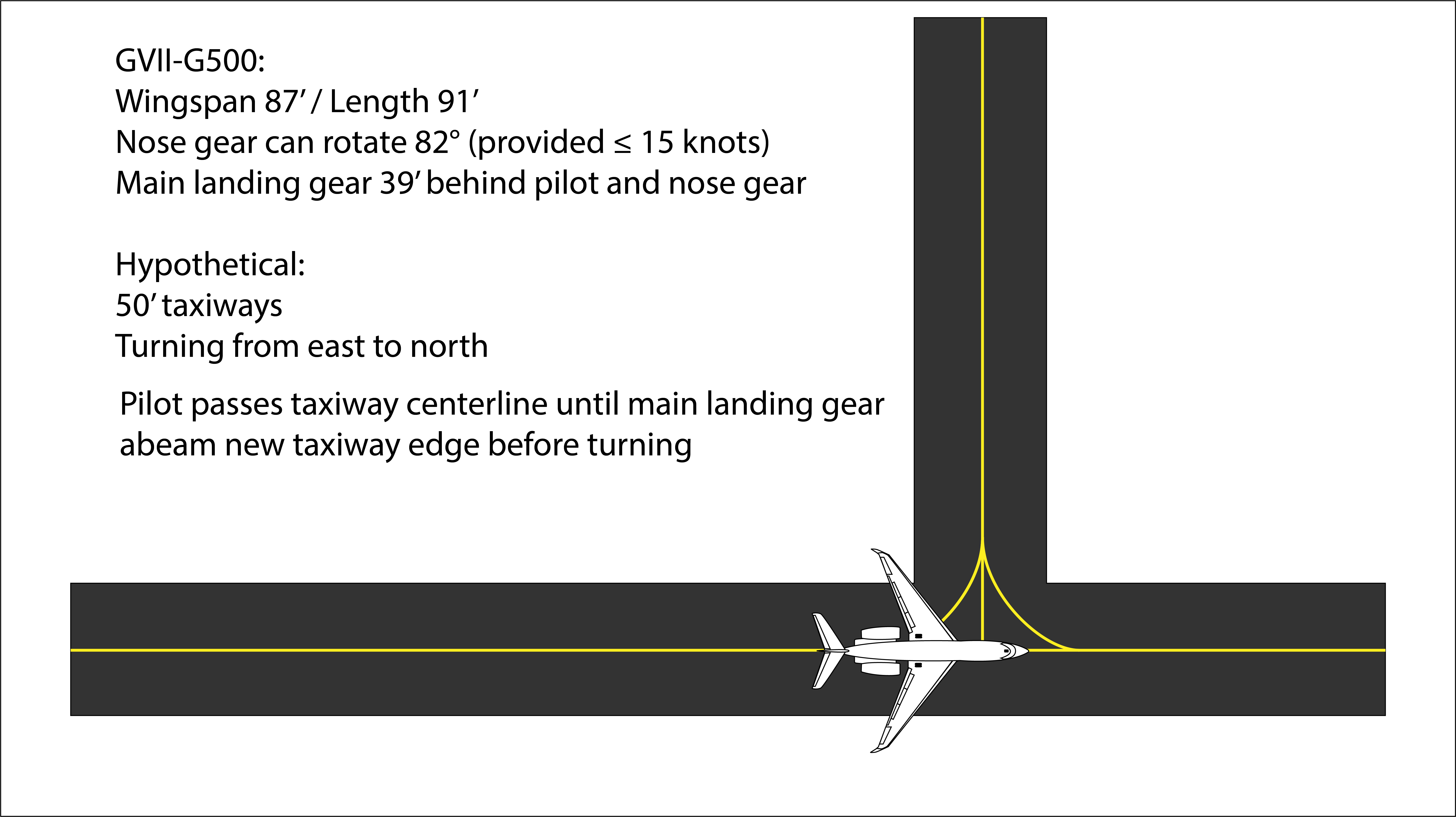

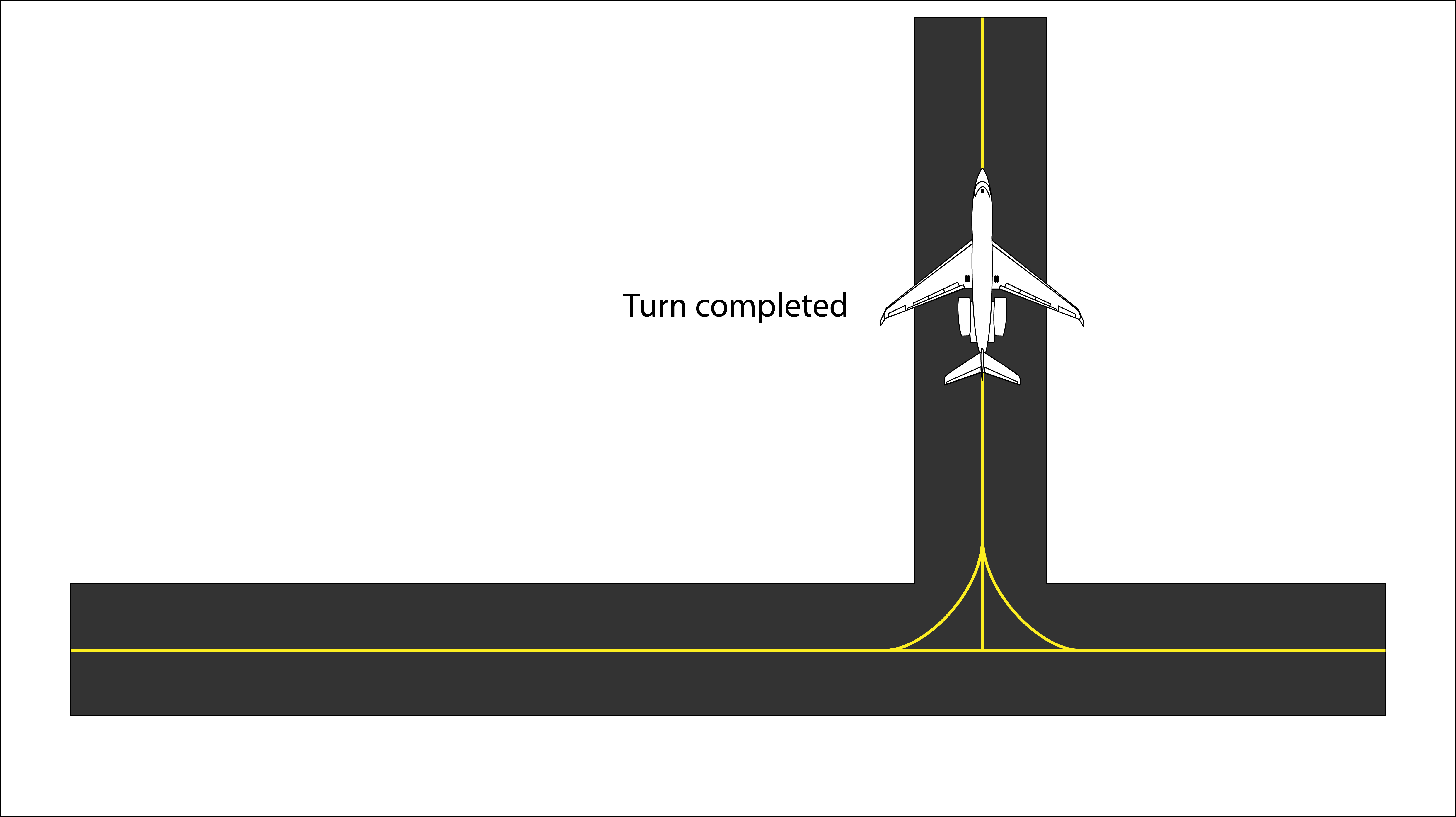

The solution depends greatly on your aircraft's ground handling capabilities, the taxiway dimensions, and your discipline level to taxi at a speed allowing the turns and to make the turn correctly. Some aircraft can turn more tightly than others. Going from a wide to narrow or a narrow to wide affords more options than going from narrow to narrow. Going too fast can make it impossible for the nosewheel to rotate to its fullest. I recommend you gather your data and start drawing a few diagrams. I've done that for my airplane here.

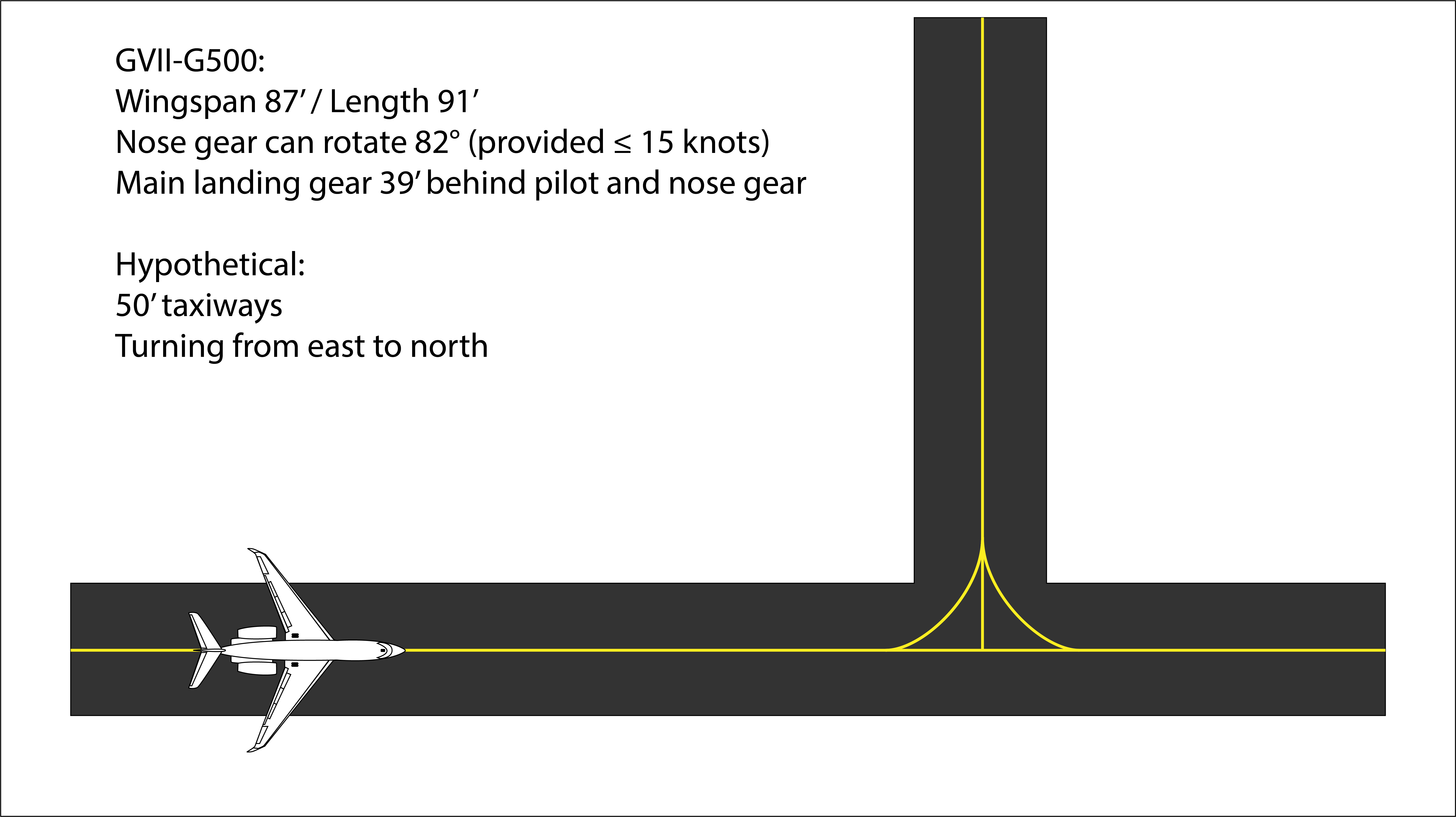

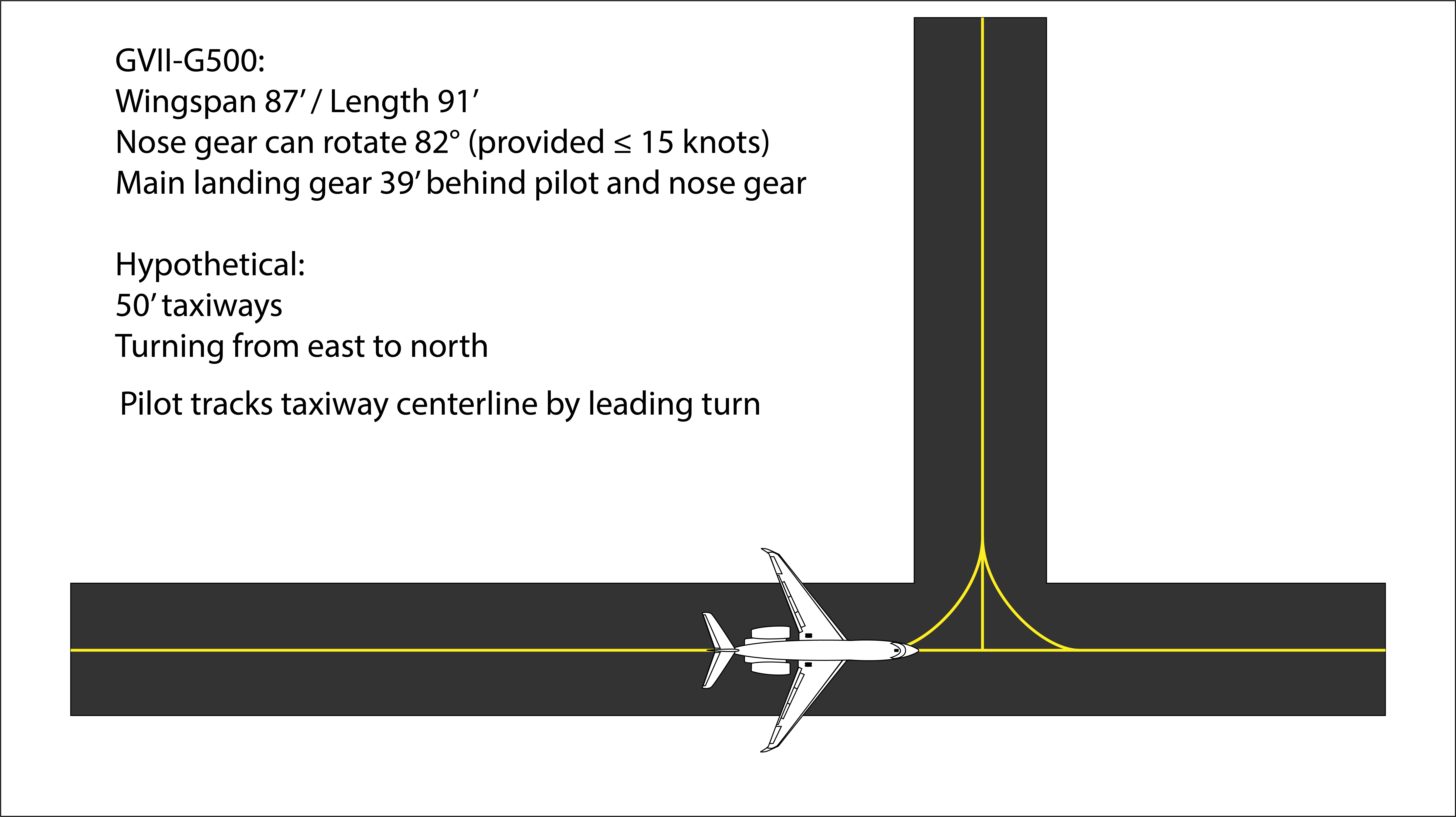

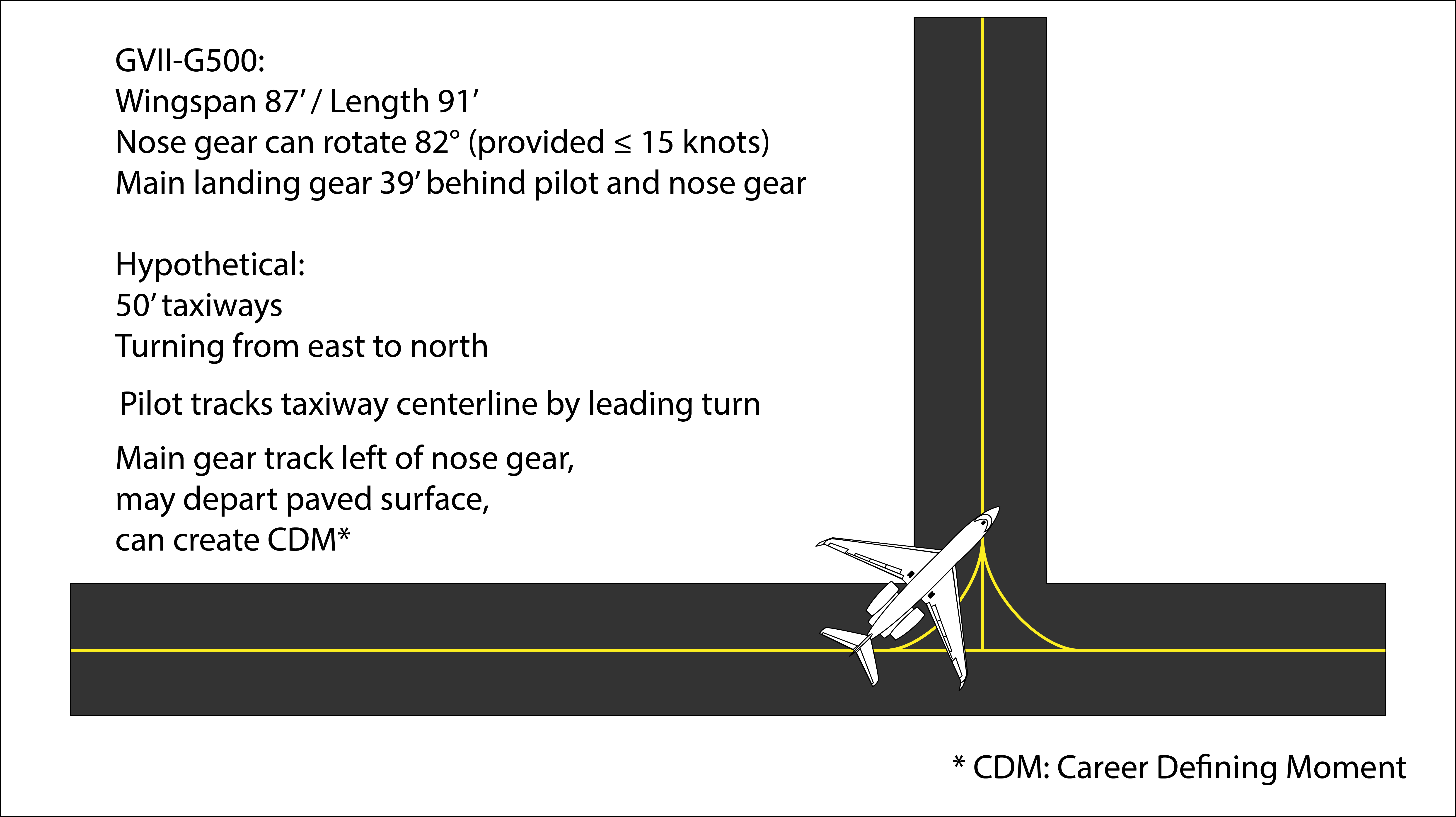

The narrowest taxiway I am willing to make a 90° turn on is 50' wide. My main gear are only 14' apart, but the nose gear is 39' forward and 50' is my personal limit for this scenario. For my hypothetical, I'll imagine taxiing east on a 50' wide taxiway, faced with having to turn left 90° onto another 50' taxiway.

The wrong way . . .

You may consciously or subconsciously attempt to keep yourself and/or your nose gear on taxiway centerline. In this scenario, if the nose gear leads the turn so as to rollout onto the new taxiway centerline, the main gear will track left.

Depending on how early you turn, or your rate of turn, the left main landing gear can depart the paved surface.

A better technique . . .

My days driving a Boeing 747 taught me to drive my eyes and my nose gear well beyond the extended centerline of the next taxiway because the main landing gear was over a hundred feet behind me. In my Gulfstream, I don't have to contend with that much distance, but having my gear 39' behind me when on a 50' taxiway is a significant issue. If I wait until the main landing gear are abeam the edge of the new taxiway, a full turn of the tiller will keep all wheels on the pavement.

Of course I don't have perfect knowledge of where my main landing gear is in relation to the new taxiway, but I do know that it is 39' behind me and that the new taxiway is 50' wide. So when my eyes pass the extended centerline of the new taxiway, the new pavement begins half that distance, or 25' behind me. And that means my main landing gear have another 14 feet to go. Gulfstream recommends "go past the extended centerline of the narrow taxiway until it intersects the main door before initiating the turn." My technique is to slow down, pass the extended centerline by about 12 feet (halfway into the second half of the taxiway), and the turn hard. I usually taxi only using rudder pedal steering but that gives me less deflection on the nose wheel. So I will use the tiller and be mindful that I can only get full deflection below 15 knots.

This aircraft makes it a little easier since the nose landing gear is right underneath the pilot. I should never be over the grass, unlike my days in the 747. But I should not be on centerline during a 90° turn if I want to make sure my main landing gear are on solid pavement.

A Hybrid Approach

The aft camera on a G450

(The gear that is on the left side of the screen is actually the right landing gear and on the right side of the screen is the left landing gear.)

Some aircraft have cameras showing a view of each landing gear in relation to the pavement, which is very handy. Be careful, however with what the camera is showing you. On each Gulfstream I've flown the aft facing camera shows the view uncorrected, it is as it would appear facing aft. So from the cockpit, left is right and right is left. It would be very easy to see the gear on the left side of the screen getting too close to the grass on its left and make a right turn, right into the grass. My technique is to bring up the screen and have the non-driving pilot tell me what is going on, such as "your right gear is five feet from the edge."

Can you use these techniques in other airplanes? Perhaps, but every airplane is different. You will have to consider exactly how far your main and nose landing gear are from you eyes and each other. You need to know how much nose wheel deflection you can have and what it takes to get that deflection. Finally, you will need some practice. Don't attempt a minimum radius turn right off the bat. Start with wider taxiways until you are comfortable. Truth be told, I am not comfortable going from a 50' wide taxiway to another. I'll look for alternatives or even get a ground marshaller just to be sure.

2

Things only get worse with speed

Flying the T-38 we used to say never taxi faster than the wing commander could walk. Nobody really did that. Years later, when block times were all important, we used to taxi at 18 knots because it made the math timing easier. I know that doesn't seem right, but a quick look at Block Times will explain that oddity.

These days the most important restrictions on our taxi speeds seem to be tire and brake temperature.

Tire Temperature Rise due to Taxi Speed

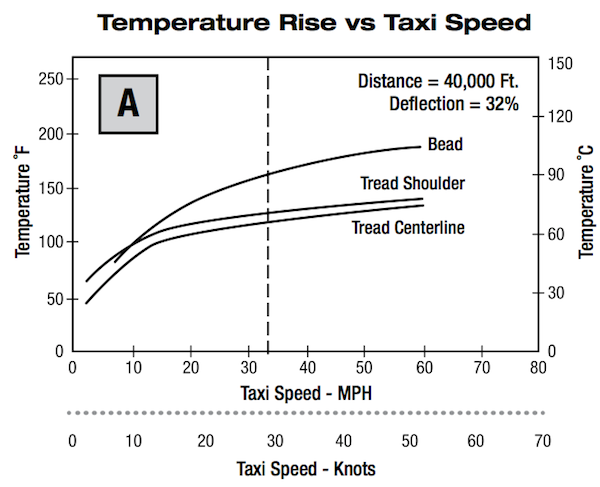

Temperature Rise vs. Taxi Speed, from Goodyear Aircraft Tire Manual, page 44.

The vertical dotted line at 35 mph (30 knots) indicates the recommended maximum taxi speed. On [this] chart, the curves constantly slope upward with higher taxi speeds. In other words, the faster an aircraft travels over a given distance, the hotter the tires will become. Many people would expect the shoulder area to generate the most heat. In reality, the bead and lower sidewall area are the hottest. There are two major reasons for this:

- All forces, in or acting on a tire, ultimately terminate at the bead. This is an area of high heat generation.

- Rubber is a good insulator; or said another way, it dissipates heat slowly. The bead area, being the thickest part of the tire, retains the heat longer than any other part of the tire

Source: Goodyear Aircraft Tire Manual, page 44

It would seem that once you've gone above 20 knots, further increases in taxi speed do not result in much larger increases in tire temperature.

Tire Temperature Rise due to Taxi Distance

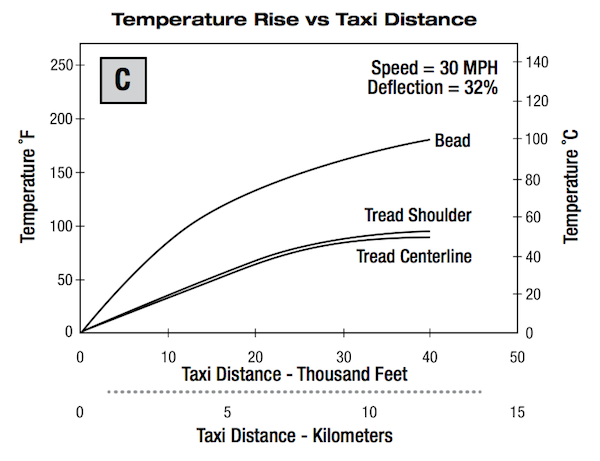

Temperature Rise vs. Taxi Distance, from Goodyear Aircraft Tire Manual, page 44.

Even when an aircraft tire is properly inflated and operated at moderate taxi speeds, the heat generation will always exceed the heat dissipated. (This is indicated by the ever increasing slope of the lines.) The farther the taxi distance, the hotter the tires will be at the start of the take-off.

Source: Goodyear Aircraft Tire Manual, page 44

I haven't seen any distance limits in most the aircraft I've flown, though the B-707 did have a warning about going any further than five miles.

Brake Temperature

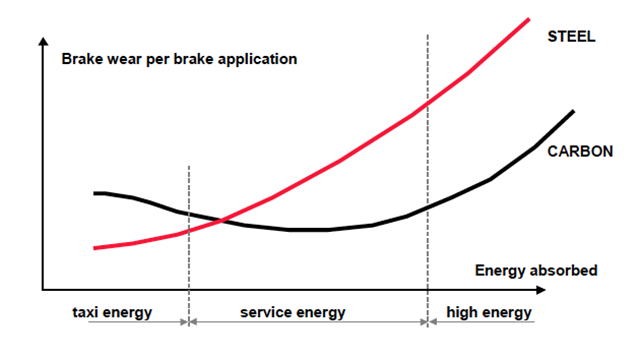

Brake wear per application, from Airbus, ¶3.2.1., Figure 5.

As shown in [the figure], energy is theoretically not the primary parameter for carbon wear, whereas it is the most important one for steel brakes. Nevertheless, applying more energy on the brake will have a direct effect on wear due to the induced increase in brake temperature.

Source: Airbus, ¶3.2.1.

The consensus from most aircraft manufacturers is you should allow taxi speed to build to about 30 knots, then brake down to 10 knots, and then repeat. This is preferable to riding the brakes. More on this at: Carbon-Carbon Brakes.

3

Trying to be smooth can turn you into a jerk

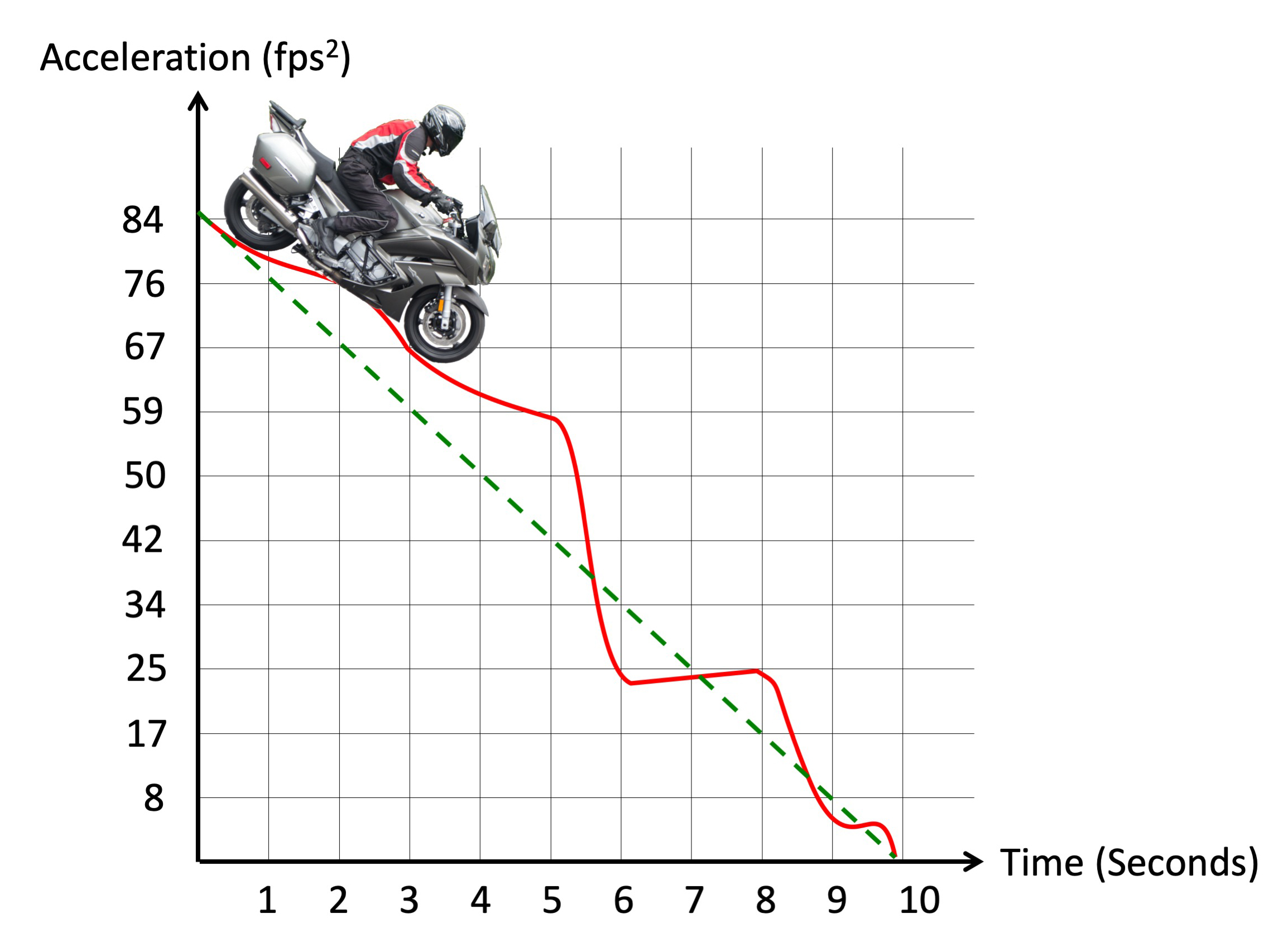

I tell a minor joke in one of my books about riding my motorcycle with The Lovely Mrs sitting behind me when I brake too hard, then relax from the brakes, then too hard again, causing her helmet to hit mine. She would then say, "stop being a jerk."

She was being technically correct, because "jerk" is an engineering term. It is actually the third derivative of position, more about that here: Flight Lessons - Mechanics. In a nutshell, it means a change in acceleration.

In the case of the motorcycle ride, I could brake hard and keep that going until I let off and that would be fine. But increasing and decreasing the braking creates the jerkiness that we associate with not being smooth.

Tiller Smoothness

Think about applying pressures to the tiller, not moving the tiller. For a tight turn, a continuous movement works best. You can hold what you have to see how it is going, but increasing and decreasing tiller deflection is what creates the side-to-side jerkiness. A lesson in story form: Smoothness

Braking Smoothness

One of the telltale signs of someone new to taxiing heavy iron is braking jerkiness, the kind that causes passengers' heads to slam against the cabin sidewall and can knock a flight attendant off his or her feet. As with the tiller, the key is to apply brake pedal pressures, not movement. And once you've done that, unless you really have to stop immediately, give it a few seconds before adjusting. Remember that increasing your pressure a few times, or even decreasing a few times, will appear smoother than increasing then decreasing, or decreasing then increasing.

4

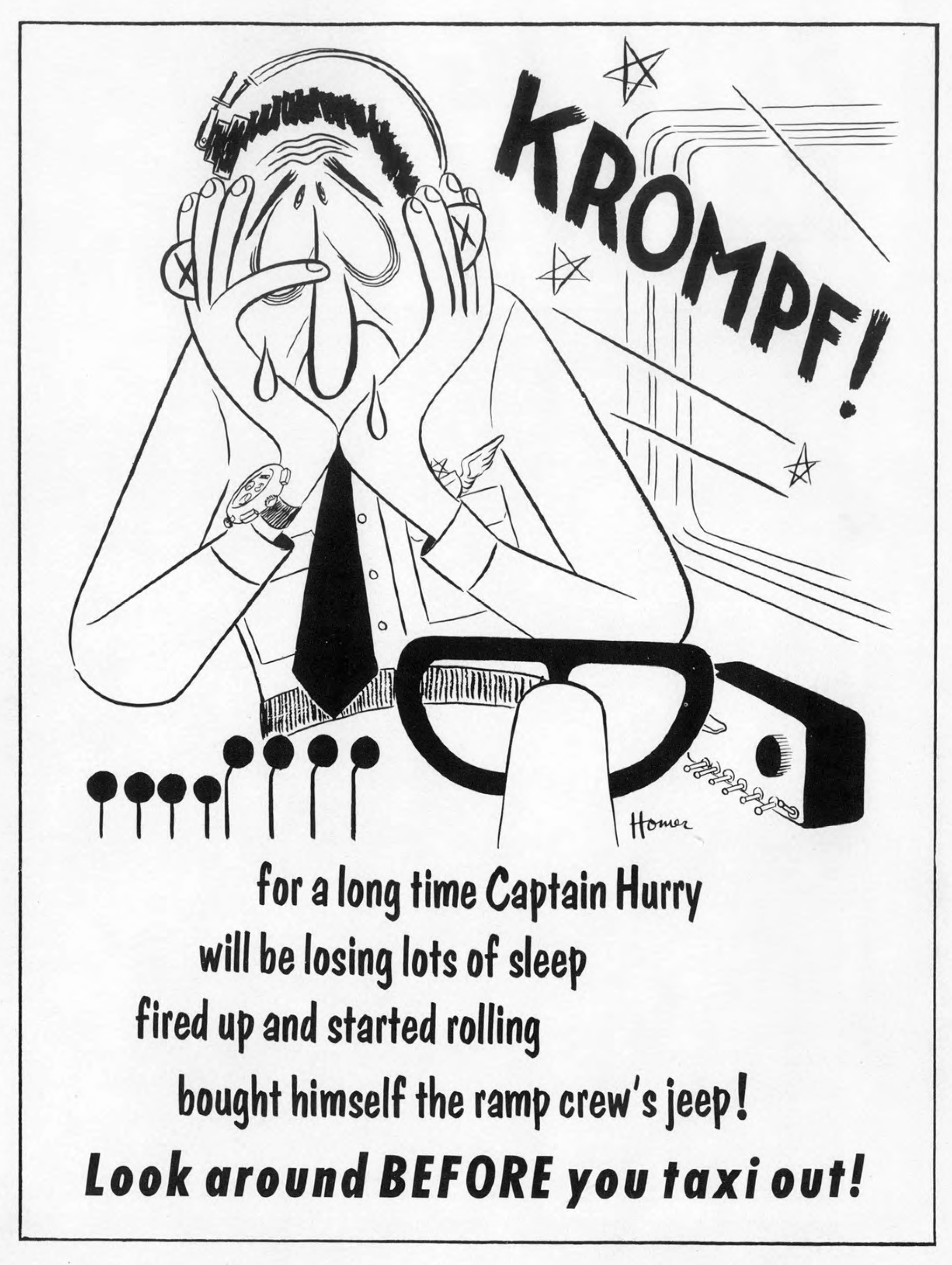

This problem has been with us for a very long time

The problem of bending aircraft metal before or after the aircraft is airborne has been with us for a very long time. The cartoon shown here is from the February 1954 edition of the Air Force Flying Safety magazine. We were taught that you should never taxi faster than how fact the wing commander could walk. This was of course impractical and nobody followed the rule, but the intent was clear. We were also told that your career could survive crashing an airplane but not a taxi accident. That one was sort of true. In any case, the intent is you have more control when you are taxiing an airplane than flying it. You can, when in doubt, come to a stop, set the parking brake, and sort things out.

There is a saying among sane motorcycle riders that has some relevance here:

Just because you can go fast, doesn't mean you have to.

References

(Source material)

Airbus Flight Operations Support: Proper Operation of Carbon Brakes, Guy Di Santo.

Goodyear Aircraft Tire Care & Maintenance Manual, Revised 1/11