Most of us grow up learning how to plan a trip by simply doing, and we usually get it right. When we are about to do someplace new, we also exercise a little caution and put in some extra effort; here again things usually go smoothly. Where I usually fall short is when I doing something that used to be routine but not recently routine. My memory fades. For these times, a checklist is usually in order.

— James Albright

Updated:

2019-04-28

Prior to departure, and preferably 24-48 hours before the planned departure time, the crew should conduct a thorough self-brief of the planned flight. The list below does not include all items that the crew should brief, but does list some of the most important items to review. The crew should review all applicable portions of the en route charts, plotting charts, orientation charts, airport charts and airway manuals.

1

Route

For the entire route including diversion and alternate airports:

- Review the route from departure airport to arrival airport. Ensure that you are familiar with how the departure procedure or SID transitions to the en route portion. Review the potential arrival procedures and ensure that there is a definable transition from the en route to the arrival portion of the flight.

- Review all FIR boundaries and ensure that the planned route and FIRs match the overflight permits, where applicable.

- Look for any notes for the route, these are usually small numbered circles or other symbols indicating special information for the route. These can point to important items such as requiring an early call to the next FIR, notes about how to handle lost communications or how what to do if you have not yet received clearance into the next FIR.

- Review the terrain and grid MORA levels for the route of flight and be aware of any high terrain near the route that could be a factor if a diversion is required.

- Review potential routings for diversion to filed alternate, and for other suitable alternates that may be required for an en route emergency.

2

Airspace

For all airspace along the route including diversion and alternate routings:

- Review the types of airspace along the entire route.

- Note transition levels and altitudes when published.

- Note any special use airspace such as military areas.

- Note any specific airspace requirements, such as RNP level, requirement for data link equipment, RVSM, etc.

- Review the en route chart end panels for any specific notes on contingency procedures for that region.

- Ensure that you are familiar with standard ICAO procedures, including Annex 2, Annex 6, Document 8168 and Document 4444.

- Review your resources for contingency procedures, noting any region-specific procedures. The Jeppesen airway manuals and the contingencies chapter of this manual are potential resources. Note that some oceanic regions have lost communication procedures unique to that region.

- Review the airway manuals for any region-specific or airspace-specific requirements or special procedures.

For more about this: Airspace

3

Airport

Review for the airports of departure and arrival.

- Airport operating hours.

- NOTAMs.

- Arrival and departure procedure notes.

- Transition levels and altitudes, altimeter setting procedures.

- Lost comm specific for that SID/STAR or airport (chart notes or airport pages).

- Expected approaches, including the procedure notes on the approach.

- International arrival parking.

- Low visibility operations.

- Taxi routes.

- Clearance and pushback procedures

For more about this: Airport Selection

4

Country

Review the country-specific section of the airway manuals and the airport charts.

- Entry requirements: This is a final check that entry requirements are being complied with.

- Review any lost communication differences unique to the country.

- Review any regulatory differences such as day/night flight and IFR/VFR differences, etc.

- Review any ATC Differences, such as holding, procedure turns, approach clearances, airspeed limits, transition levels/altitudes, altimeter settings, etc.

- Review any additional procedures unique to the country.

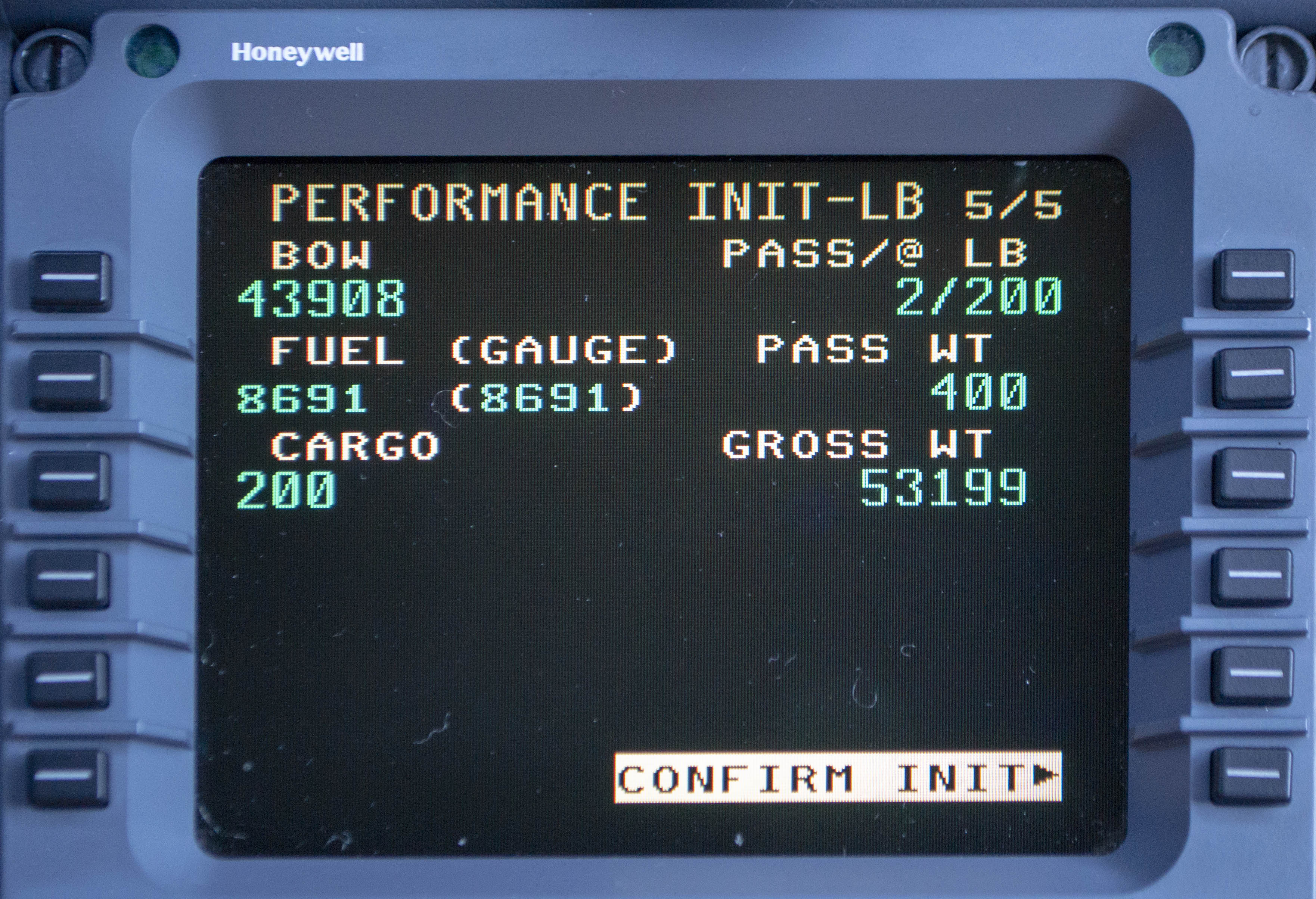

Dear James,

What’s the story behind the following Cruise checklist item in my Gulfstream: FMS Fuel Quantity....UPDATE?

I’ve heard that someone complained to GAC about consistently seeing a fuel quantity disparity between the FMS and the gauge so GAC simply added this item to the checklist. It’s there any truth to that or is that a myth??

Signed, R. Fader

Fort Lee, New Jersey

Dear Mister Fader,

No that step is an important part of how you detect a fuel leak. The FMS performance computer is constantly monitoring how much fuel the engines should be burning to produce that number. You check it and reset it on level off and, I think, you should repeat that every hour. If there is a wide discrepancy, you should suspect a fuel leak.

Few Gulfstream pilots really understand how to do this. It becomes especially difficult when you take on large amounts of fuel. After you level off the fuel the FMS thinks you have could be several hundred pounds high or low depending on the starting temperature of the fuel and, therefore, its density. Who is right? They both are. The FMS gave you a more accurate idea of how much fuel was burned, the fuel gauge gives you a more accurate idea of how much fuel you have. It is important to understand both concepts. Now you want to reset the FMS so it again agrees with the gauge. Your SOP should tell you to repeat that process every hour. As the flight progresses, the disagreement should get smaller and smaller.

So how does this help with a fuel leak? Let’s say you develop a small fuel leak somewhere in the system, it really doesn’t matter where. But for some reason you are losing 1,000 lbs every hour. Let’s say this leak develops on hour 3 of an 8 hour oceanic crossing from White Plains to Rome. Chances are you will catch it since you make these checks against your master document. Now let’s say it happens on hour 3 of an 8 hour flight from Cape Town to Rome and you aren’t doing this master document hourly check. If you noticed the FMS was off by 300 lbs on level off (not unusual) and never checked it again you could be at risk. Now let’s say the leak starts right after level off and you are down 1,000 the first hour, 2,000 the second hour, and so on. By the time you might notice, it may be time to put the airplane down promptly in a location you would rather avoid. But if you checked at hour 2 and noticed you were down 1,000 lbs, you would be warned that something isn’t right.

James