If you are an Air Force or a Navy pilot today, the airlines beckon. But are you sure that is where you want to go? A career with corporate aviation can pay as well (or better) and can be more secure. But just as there are airlines to avoid, there are more than a few wrong turns you can make when looking at a career with corporate aviation. Let's look at that.

— James Albright

Updated:

2019-09-20

Most Air Force and Navy pilots never pay much attention to corporate aviation these days because the airline option has become a very good one. The airlines are more stable than at anytime in the past, pay has improved across the seniority spectrum, and there are lots of openings. (The pilot shortage is real.) But if you are about to leave the Air Force or Navy, you might be better off going in another direction.

A note to my non-USAF or USN readers. Some of what follows may offend and I am sorry for that. But Air Force and Navy pilots can only leave the service after ten years following their initial pilot training and in that time they build a lot of experience. Sure they may not know the first thing about a lot of what we do, but that is easily taught. I feel it is my duty as a veteran and someone interested in the best for our industry to encourage these pilots to show up at the head of the line. They deserve to do just that and once we hire them, we will all be better off in the bargain.

1 — What is "corporate aviation?"

4 — Who provides a higher quality of life?

5 — Who provides more job security?

6 — Who provides more job satisfaction?

7 — When should I make the jump?

8 — What are good sources of corporate aviation information?

9 — What can you tell me about preparing a good resume?

1

What is "corporate aviation?"

There are a few terms to wrap your head around and they will be important if you want to filter the "low end" from the "high end." But before we do that, let me say that there is nothing wrong with what I call "the low end" of corporate aviation. The turbo props and small jets are perfectly good options for most pilots and can be considered as an entry level step into a larger world. But a pilot with Air Force or Navy training can and should expect to bypass this step and go directly to the front of the line.

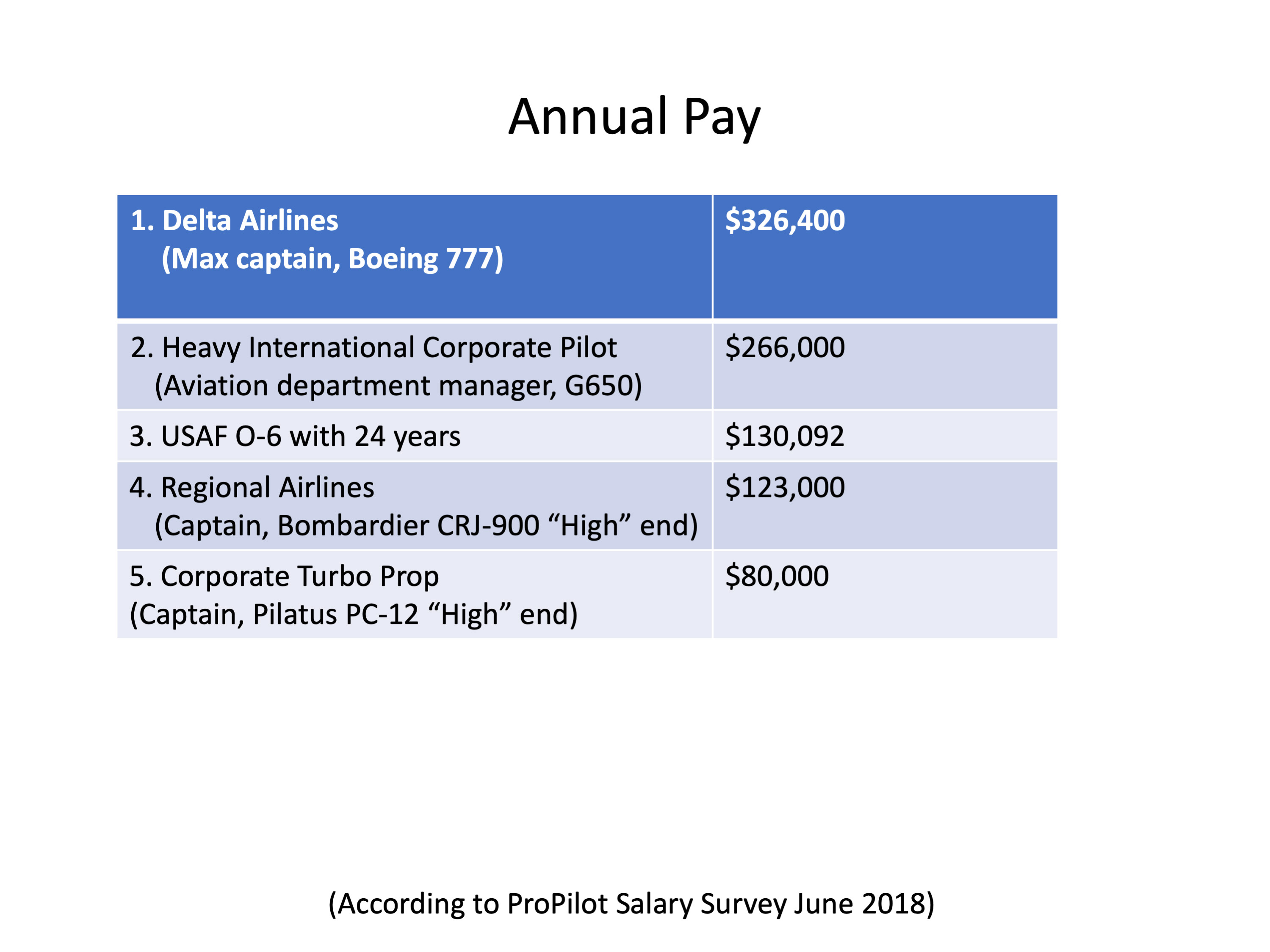

The pay cited here is from a 2018 Professional Pilot magazine article and represents only what respondents have submitted. You can easily find pilots making more and less than the numbers given. The latest generation of international Gulfstreams, for example, pay over $300,000/year in some locations. That's almost double of what the survey indicates. But these numbers at least give you an idea for comparison's sake.

Turbo Props

Turbo props vary from single-pilot operators, such as the Pilatus PC-12, to higher end King Airs. The 2018 Pro Pilot pay survey varied from a low of $44,000/year for a captain to a high of $111,000/year for an aviation department manager.

Light Jets

Light jet pilots share many of the issues faced by the turbo prop pilots but can be a step up in terms of pay and perhaps a bit better quality of life. Pay varies from a low of $43,000/year for a first officer to a high of $95,000/year for a captain.

Mid-size Jets

Mid-size jets are a step up, require two pilots, and can vary from the same issues faced by the smaller jets or can be very good, depending on the flight department. Pay varies from a low of $42,000/year for a first officer to a high of $132,000/year for a captain.

Large Cabin "Classic" Jets

Many pay surveys differentiate the large jets into domestic or international but these days that fails to capture what you need to know in terms of pay and quality of life. I think it is more helpful to consider the older versus the newer. You can buy a used GIV for $3 million where a newer GVII will set you back around $50 million. The operator of the newer jet is likely to have higher pay and provide pilots a better quality of life. If you are flying a "classic" version of these airplanes, expect much less. Pay for a first officer of an older GIV or Falcon 900 is as low as $60,000/year. For a captain it can be as high as $150,000/year.

Large Cabin "Latest Generation" Jets

If you are flying a corporate jet capable of long haul, international travel, expect everything to be better. If the airplane is less than ten years old, chances are it will be even better still. The low end of the pay scale is $76,000/year for a first officer, the high end for a captain is $168,000/year and for a flight department manager is $266,000/year. Note that many corporate operators are reluctant to discuss pay, especially as the numbers get higher. I know of a lot of pilots in this category doing $300,000/year and better.

Airline Type Jets

Many pilots outside of corporate aviation are surprised to hear that with very few exceptions, the airline type of jets (think Boeing 737, 757, 767, and even 747) do not pay as well as the latest generation of Gulfstreams, Bombardiers, and Falcons. Pay can be as low as $65,000/year for a first officer and as high as $162,000/year for a captain.

The Part 91, 121, 125, and 135 Decision

Part 91 refers to non-commercial operators flying aircraft with payloads of 6,000 lbs. or less. Part 125 are similar but with larger payloads. Pay and quality of life tend to be better but there may be less certainty in scheduling. This section of corporate aviation could be working for a private family or a large multi-national company. I flew for Compaq Computer, for example, under Part 91. Most corporate aviation pilots target this part of corporate aviation as having the best pay and quality of life, as well as the highest level of job security. Simulator check rides can be progressive, meaning you train and check simultaneously.

There is a subset of Part 91, known as 91K because the rules reside in Section K of Part 91. This is where many fractional operators — think NetJets or Flexjet — manage to fly paying passengers but without the bother of commercial rules. In theory, the passengers own a portion of the jet. These operations tend to be run like airlines, often including seniority numbers and unions. Pay tends to be a bit lower than in some purely Part 91 operations.

Part 121 and 135 are commercial operators. The rules tend to be more restrictive and the check rides are inflexible.

Flying charter bears some mention too. On the low end of corporate aviation, flying charter can mean being on call for several days and not having a good variety of destinations. On the higher end, it can be like being paid to be a tourist. I did this for a number of years in a Gulfstream GV and rarely had a pop up trip and got to see the best parts of the world with ample time to explore.

2

When can I make the jump?

In 1979 an Air Force or Navy pilot owed Uncle Sam 4 years of service after getting his or her wings. Since most of these pilots were between 23 and 25 years of age, they could jump to the airlines between the ages of 27 and 29. That's where most airline pilots came from back then, which meant if you were 30 or older, you were too old. You basically had a two year window for making the jump.

All that has changed. These days the pilot training commitment is 10 years and the Air Force and Navy produce far fewer pilots. Since airline deregulation the number of pilot jobs has gone way up. The airlines are hiring much older pilots. (This year United Airlines hired a 59-year-old.) That's good news for all pilots.

And the trend will continue. That 2018 Boeing study has been recently revised upward, showing the world will be short 700,000 pilots by the year 2037; and 150,000 of those will be in North America.

So the bottom line is that you can jump at your first opportunity, or you can wait for a time that is right for you.

3

Who pays more?

Just five years ago the distribution was set in stone: airlines didn't pay that well until you either made captain or lasted five or more years as a first officer. You had to worry, however, that if your airline was taken over or folded, you would have to start over. In the corporate world you were paid well in the long haul equipment, poorly in the turbo props or light jets, but as you built time it didn't matter if your job went away, you didn't have to start over. On the Air Force and Navy side of the house, pay was poor but every now and then a retention bonus kicked in and life was a little better.

All of that has changed.

The Airlines (major carriers)

Most of the major carriers have undergone big shake ups the last ten to twenty years and seemed to have established an equilibrium of sorts. In my opinion, if you get hired by American, Delta, Jet Blue, or United, you should have a job for the rest of your career if you manage to stay healthy and out of trouble. The $326,400 annual pay shown in the study doesn't include profit sharing, international overrides, per diem, and other credits. I know several captains who tell me they are doing better than this. Life for first officers is better too. At American, a first officer can expect $150,000-plus after the year on probation. I've heard from some that double that by bidding unpopular schedules.

Latest Generation, Long Haul Corporate

If you get hired by a very good corporate flight department flying the most modern equipment, you should be able to get a salary in $200,000 to $300,000/year starting. Some pay much less so you need to understand why the pilots are willing to work for less. It could be a great location, a great benefits package, or some other intangible. Or it could be that they are grossly underpaid. The chart's $266,000/year is low. Most corporate flight departments keep their salaries secret and if you are making obscene amounts of money, you are probably unwilling to share that with the world. There are also geographic differences. From high to low, salaries vary from the New York City area, San Francisco Bay Area, the Pacific Northwest, the Northeast, the Southwest, the Chicago Area, the Southeast, the Midwest, and Texas. Yes, your pay in Texas will be the worst. But you will also have one of the lowest cost of living.

The Airlines (regionals)

A senior regional captain can make $120,000/year while being able to control his or her schedule through seniority. If you are living where you want, that isn't such a bad deal. No wonder some regional captains decide to forgo the majors. Pay and quality of life for a first officer is much worse, with pay as low as $34,000/year for flying an RJ. My advice to any Air Force or Navy pilot: do not consider a regional airline. You can, and should, do better.

"Classic" Large Cabin Corporate

Pay for many of these old birds varies wildly. At one time the airplanes were very expensive and the pay matched the airplane. But as the airplane lost value salaries may or may not have followed. A classic Gulfstream or Falcon might be a great option, but you need to investigate. Someone flying older equipment may not be around for the duration of your pilot career.

Corporate Turbo Prop and Light Jets

These are fine options for a civilian pilot coming through the ranks or even for retired airline pilots. But I wouldn't consider them for any relatively young (let's say 45 or younger) Air Force or Navy pilot. Set your sights higher.

4

Who provides a higher quality of life?

Of course this is subjective and there are wide variations from one airline to another, as well as from one corporate flight department to another. But please consider the following over generalizations as a starting point, from which you should ask further questions.

The airlines — A few things to consider

Depending on the airline and their staffing levels on the day you get hired, you might find yourself commuting to your domicile. This used to be okay in that you got "space required" seating which was often in first class. But these days many airlines will put paying customers ahead of you and they would sooner upgrade a paying customer to first or business class before giving you the chance.

Many airline pilots will contribute to a "crash pad" where the conditions are not what you are used to; do you really want to be reliving your college dorm days? By far the worst situation is those forced to grab a few Z's in the pilot's lounge. There have been a few crashes where this was found causal.

You can expect to work long days and a lot of days each month when starting out. Things do get better after a year or two or more. I've heard of some pilots being on reserve for several years. It may be many years before you are one of those airline captains who works only 15 days a month.

But once you have a fair amount of seniority, you can be the master of your own calendar. Being paid well allows you to maximize the time off but you and your family have to survive the years it takes to get there.

Corporate aviation — A few things to consider

There is a wide gap between the top and bottom end of corporate aviation. If you get hired at the bottom and stay there, it will be a miserable existence. The pay is poor, the equipment isn't very good, your schedule will be brutal, and life will be awful. If you get hired at the top, pay is immediately very good, the equipment is state of the art, your schedule will be light, and life will be great. You can start at the bottom and propel your way quickly to the top, but you can bypass the bottom entirely. When I got hired at Compaq the civilians were fond of telling me that I didn't pay my dues. I told them being shot at is a form of paying dues they couldn't understand, but that didn't stop the whining. So I ended up saying, "Paying dues is for chumps."

A word about equipment: most of ours is better than what the airlines have.

A word about starting at the top: our most recent new hire started in the mid-200,000 range, flies an average of 20 hours a month, works no more than 10 days a month, has the rest of the month off with no duties, and just got typed in the most modern thing flying today (A Gulfstream GVII).

The Air Force — A few things to consider

Okay I am not the expert here but from my 20 years the following comes to mind. I had to move 13 times in 20 years. I briefly saw some combat flying but I never had a remote assignment or had to deploy; these days I have heard remotes are more frequent as are deployments.

I've also heard the promotion rate to major is above 95 percent and that if you want to do twenty years in the cockpit you can; things are quite different. Bonuses are much higher and last longer. All of this plays into the next question.

5

Who provides more job security?

I once had a pilot who quit for a job flying with the U.S. government because I couldn't guarantee his job will last for the next ten years. I didn't push back because, to be honest, I was happy to see him go. But job security is something to consider.

A 2018 Boeing study says the world will be short 635,000 pilots for fixed-wing aircraft by 2037, 127,000 in North America alone. No matter which route you take, you should be able to keep flying professionally if you stay healthy and stay out of trouble.

The Airlines — Mostly good, some risk

If your primary goal is to keep flying big airplanes until you turn 65, then the airlines are probably the way to go. You will more than likely have a union to protect you. The primary risk used to be airlines going out of business or being taken over. In the former case you were out on the street and had to start the process all over. In the latter you were at the mercy of the contract writers. I had friends at Northwest who merged into Delta and did great. I also know pilots at TWA who became American Airlines pilots but went from the top of seniority to the bottom, had to give up their captaincies, and were soon furloughed for a very long time.

These days the risks are greatly reduced. Most of the weaker airlines are gone and if you get hired by a major, you should be okay for the foreseeable future. As a result of the TWA to American line number nonsense, current law says your date of hire goes with you in the event of a merger. But if your airline goes out of business, you have to start over.

Corporate Aviation — Mostly good, some risk

I hear the average lifespan of a corporate pilot is only three years and during my first ten years as a civilian that was about right. But that isn't as bad as it may sound. If you are flying a jet of the latest generation as an international captain and your company goes out of business, you don't have to start over as a copilot on something smaller and older. Companies hire you for what you can do, they don't automatically put you at the bottom of the pilot pool.

Not all of corporate aviation is as susceptible to downturns in the economy, but some are. One of my jobs went away in 2008 and I bounced between two jobs before landing the one that has lasted me ever since. (Ten years and counting.) Compared to today's major airlines, I think job security in corporate aviation is lower if you are considering the particular job. But it is higher when you consider it as a profession: you will end up flying longer, but not necessarily with the same company.

You might want to consider age limits too. In the airline world you can fly domestically until the age of 65. That limit does not exist in corporate aviation, though some countries will not allow you to fly as captain.

The Air Force — Fair at best, some risk

Job security as a pilot in the Air Force is way up. From what I've heard, you can stay in the cockpit if you want and will not be threatened with non-flying duties all the way through the 20 year point. But keep in mind that is the situation as it stands today.

When I was at the Pentagon the Air Force budget was cut to the bone and we went from pilot bonuses to pilot severances overnight. The weirdest case I know of happened to a B-52 pilot married to an incompetent transportation officer. He was considering getting out just as his wife got passed over for first lieutenant. They were wondering about the loss of income when the AF offered him $12,000 a year if he agree to stay for five more years. That was a lot of money back then and he agreed. Two years later the AF decided they had too many pilots and waived the years he had left on the bonus and paid him $30,000 to get out early.

During that time the promotion rate to major for pilots was far below non-pilots and if you didn't make it you got one more chance and then you got thrown out. The Chief of Staff of the Air Force was shown the statistics that he was creating a pilot shortage about five years in the future and he said he didn't care. "I've got to fix today's manning today, or I won't have a tomorrow."

So please keep that in mind because it was true then and it is true today: the needs of the Air Force trump yours.

6

Who provides more job satisfaction?

Here again we have a qualitative judgment that depends on what you want out of the job. My opinions may be wrong for you, but they should give you points to ponder.

The Airlines — "All I want to do is fly airplanes."

I've heard this during most of my careers (as an Air Force pilot as well as a civilian). If you don't want to be bothered with anything outside of the cockpit, then the airlines are for you. Everything is handed to you before you show up at the airplane: the flight plan, the manifest, the weather, etc. But it goes beyond that. If you need to know something, they will tell you. Let's say you were flying domestic and start a new line that involves crossing the pond. You won't be bothered with a lot of the details, you will be taught only what you need to know to competently cross that particular pond. If you are interested in going beyond that, you can but it will be up to you.

Corporate Aviation — "I would like to master as much as I can."

If, on the other hand, you want to get into the nuts and bolts of what it takes to fly airplanes, I predict the airlines will bore you. In corporate aviation you may be responsible for route selection, diplomatic clearances, aircraft licensing, slot negotiation, navigation fees, the list goes on and on. During my first year as a corporate pilot I was put in charge of obtaining FAA letters of authorization for two aircraft and rewriting the company operations manual. During the last year I have been working on negotiating, purchasing, and outfitting a new airplane. Our pilots are responsible for worldwide operations, not just an agreed upon monthly schedule. To be honest, I do feel like I am constantly playing catch up and that I am never a master of all that I need to know. But I prefer it that way.

Asking around, recently Air Force vets turned corporate pilots tell me the following are aspects of their jobs they find to be at a higher level than what they would have expected from the airlines:

- Deep job satisfaction

- Dynamic team environment

- Ability to make changes/improvements

- Very diverse set of locations (i.e. International flights one week then landing at small uncontrolled fields in Nebraska the next)

- Familiarity with the aircraft/equipment

- Relationships with the maintenance team

- Corporate aviation community

The Air Force — "I want to do something good."

While serving your country it is easy to lose sight of the fact you are doing just that: serving your country. You may not think of yourself as a patriot, but your country bestows that honorific upon your shoulders. Comparing my twenty years in uniform with my twenty years out of uniform is true that I am being paid more, have a higher quality of life, and feel more job security. But I also feel like a bit of a mercenary.

7

When should I make the jump?

So, you now have the flexibility of leaving when you want. You no longer have one bite at the apple, you have several.

The case for now

A friend of mine at American Airlines advises that date of hire is key: the sooner you get out to make the big bucks, the sooner you will be making big bucks. I met him when we were both first lieutenant copilots flying EC-135Js (Boeing 707) in Hawaii. He got hired by American in 1984 and has never looked back. He retires next year with 36 years with the airline, 30 of those as captain. He's never been furloughed and tells me that he never took a pay cut or had to give up his captain's seat. He was very lucky, but he also has a bit of a memory issue. I remember they came very close to a strike which was averted at the last minute. He never had to give up the left seat but he was once a check airman and had to give that up. He never took a pay cut, but his union at one point agreed to work more hours for the same pay. That sounds like a pay cut to me. But, still, he has had a good, high paying career.

The case for later

I also know a lot of airline pilots who spent years as carpenters and car salesmen when furloughed. A number of them, like the TWA pilot already mentioned, had to start over a number of times. A college classmate of mine has worked for six airlines.

As an Air Force pilot you should expect to go to the head of the corporate aviation line and immediately have a higher quality of life at higher pay. But you don't have to get out now to do that later. You can wait.

No matter which direction you head — the airlines or corporate — there is something else to be said for waiting until twenty years in uniform. I got out at twenty years and every month since I've got a check from Uncle Sam equal to 50% of my base pay on the date I retired. Your rate might be less at 20 or more if you go beyond 20. But consider that as the best investment you ever made turned into an annuity. I have an airline friend that tells me my pension wouldn't even pay his taxes. I tell him it has paid off a mortgage and put two kids through college.

My advice

If I was in uniform today, I think my game plan would be pretty clear. I think I would continue to serve and see how each promotion and assignment plays out. If I get passed over for promotion, life as a civilian pilot beckons. If the next assignment is good for my family and my personal development, I would accept the assignment. Otherwise, I would punch out. This is a decision that can be made over and over again, until the day you finally decide to punch.

8

What are good sources of corporate aviation information?

I think most Air Force pilots are well versed at the airlines decision but not so much about corporate aviation. Most of it is word of mouth, we in corporate aviation do a lousy job at self promotion. You might give my earlier article a look: Career Advice for Air Force Pilots. Here are a few other sources.

The National Business Aviation Association

The NBAA is in the business of supporting us in corporate aviation and their website is a main source of information for many of us. You will need a membership for most of it, but you can view the "What is Business Aviation" section and download a fair amount of content without a membership. It is a good introduction on the subject.

Link: https://nbaa.org/

Bombardier Safety Standdown

Despite the name, this event if for all of corporate aviation and does have attendance from parts of the Air Force, it is well worth your while. But even if you can't make it, there is a lot to learn from the website and the many downloadables.

Link: https://safetystanddown.com/en

Business & Commercial Aviation Magazine

As an Air Force pilot you are probably very familiar with Aviation Week & Space Technology. Well, believe it or not, the largest part of that network is found in the magazine Business & Commercial Aviation. Just viewing the many free articles will get you up to speed on all things corporate aviation. I have been writing for them for quite a while and have posted the articles I've written here.

Link: https://aviationweek.com/business-aviation

Local Airport User's Groups

Lots of corporate aviation airports have robust users groups that hold monthly, quarterly, or yearly meetings that offer great opportunities for networking. There is no better way to discover a great job opportunity than to introduce yourself to the chief pilot, director or aviation, or even just one of their line pilots. A few to consider:

The Greater Washington Business Aviation Association: https://www.gwbaa.com/

The Massachusetts Business Aviation Association: https://www.massbizav.org/

The SOCAL Aviation Association: http://scaa.memberlodge.com/

The Teterboro Users Group: http://teterborousersgroup.org/

Other sources

Many of the blogs and head hunter sites are tailored to the aspiring airline pilot, but you will find good information about the pilot job hunt in general and corporate aviation in specific, if you look for it. Just an example:

Don't forget social media. There is a Facebook page, https://m.facebook.com/groups/1603441796587702?tsid=0.5306563103868412&source=result, but you will have to join to become a member first. There are over 29,000 members.

9

What can you tell me about preparing a good resume?

There is a real art to writing a resume and years as an Air Force writer might not be the best training. I write resumes the same way I wrote effectiveness reports and promotion recommendations. Write so that your mother could understand it and would be proud. If it is more complicated than that, you need to edit.

The Airline Transport Pilot rating

You need this. Even if you do it in a small twin-engine airplane, you need it. If you don't have it on your resume, most employers will stop reading.

Type Ratings

A Navy pilot friend of mine retired as a 2-star admiral and bought himself a Gulfstream GV type rating for around $50,000 and spent the next ten years happily flying contract on that rating. These days a type rating can set you back $120,000. I know it was (or perhaps still is) common to buy a Boeing 737 type rating for a tenth of that as a first step to getting hired by Southwest Airlines. Should you do that?

I don't think that step is necessary for an Air Force or Navy pilot. If the flight department you have in your sights is unwilling to pay for your type rating, I think you should move on.

I received a hybrid question recently that might be worthy of consideration. Let's say you are an Air Force pilot flying a Gulfstream GV and already have your ATP and a GV type. Should you spend the $3,000 for G450/550 differences? One again, I don't think so.

Flying Time

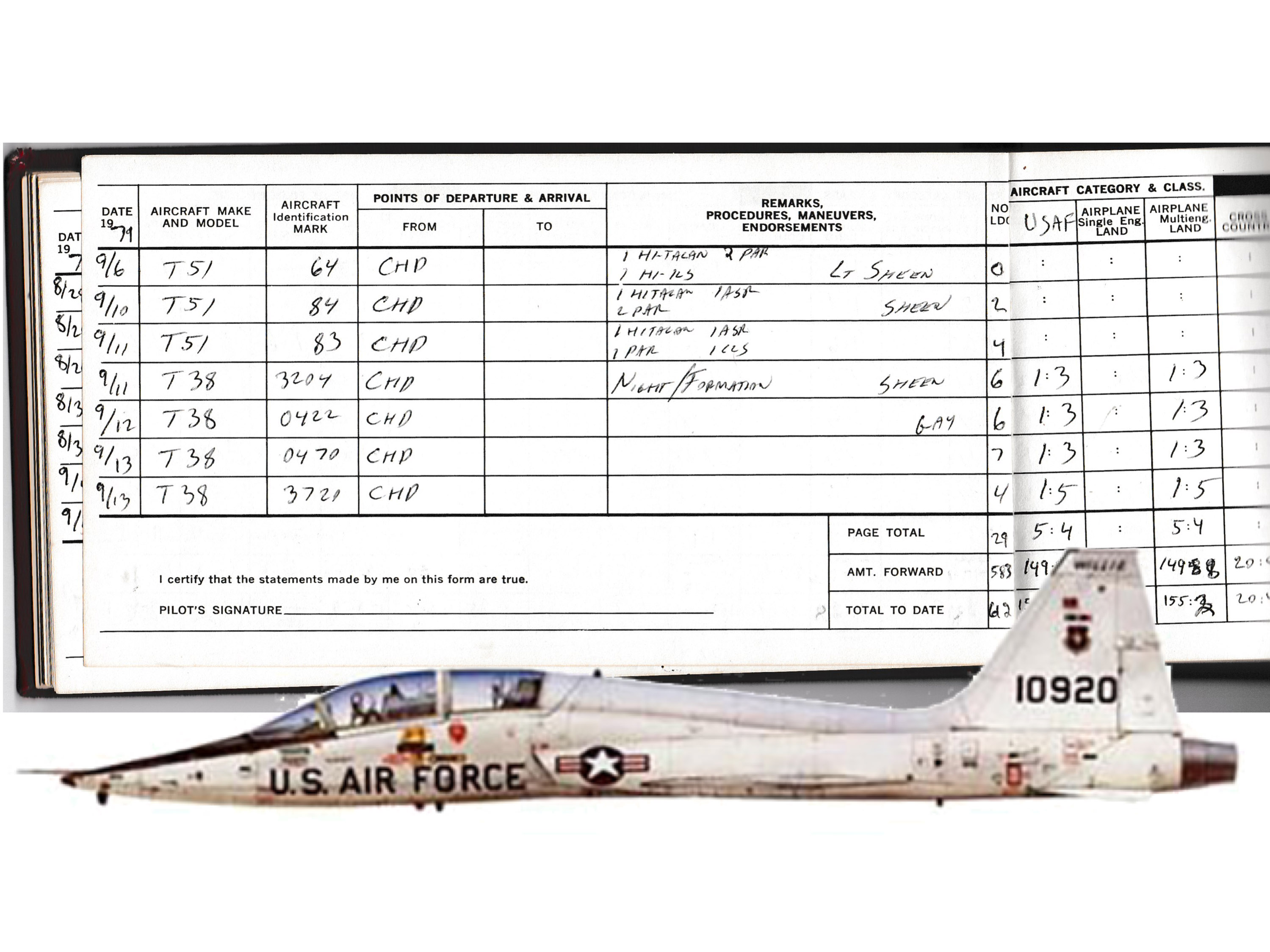

You need to prepare yourself for the gap between your logbook and your civilian counterparts. Some pilots go through the trouble of adding 0.3 hours to every Air Force sortie only to be surprised when the interviewer asks if you've done that or not. Back when the market for airline pilots was mostly Air Force and Navy, this was a common practice and interviewers knew that. These days the interviewer might be confused. My advice is to leave your hours alone and be prepared to answer questions about it. With corporate aviation interviews you might get a question or two and it would be wise to have a confident answer. Allow me to replay an interview I had for my second civilian job. A bit of background first. I had three non-flying periods in my Air Force career so ended up flying on 15 of those 20 years. I finished with 5,000 hours. My first civilian job only lasted two years and added 1,000 hours to my logbook.

- Interviewer: We are concerned about your lack of experience.

- Me: How do you define experience?

- Interviewer: Well, hours, obviously. With only 6,000 hours you have only half the experience of the next youngest pilot and barely a third of the most experienced. We are hiring a third pilot. With only three pilots we want to make sure each is highly experienced.

- Me: I have double their combined jet time and quadruple their combined international experience.

- Interviewer: Is that important?

- Me: I think so.

(I was hired.)

General advice for your resume

- Keep it to one page. If you have more than one, the person screening the resume is apt to skim it, and that increases the chance the screener doesn't forward it to the decision maker.

- Keep the fonts simple and 12 pt. If the resume becomes an eye test, the screener is going to pass.

- Keep in mind that the resume gets you the interview, the interview gets you the job. The purpose of the resume is to make the reader realize you should be their next best hire.

- Tailor the resume for the recipient. An airline resume is going to want to see that you've flown into some challenging airports, big and small, and have upgraded as far as you could given your time. A corporate operator is going to want to see that you can do more than just fly the airplane. Both kinds of operations will be impressed with a background in safety, especially safety school. Ditto for instrument instructor school.

- List Total, PIC, SIC, multi-engine, and instrument time as a minimum. Do not waste space on student time. Combat time is of little interest unless you are interviewing for a hazardous duty job.

- Make sure every line of "work experience" is used wisely. You don't want to have gaps in employment, but you don't want to waste more than one line to cover something that doesn't help your objective. I once interviewed for a job that involved managing a flight department's assets so my time at the Pentagon took more than one line. But for those jobs that were primarily as a pilot, that experience only garnered one line.

- Prep the resume with the interview in mind. You should have a short, confident story to tell about every line on your resume. Not all interviewers do this, but most will pick things from your resume to talk about. I once interviewed a pilot with nuclear weapons transport qualification in a C-141. I know a little about this but when I asked the interviewee said he wasn't permitted to talk about it. I suppose he wanted to impress me with his security clearances. I was unimpressed that he thought he couldn't talk about it but he could post it in his resume.

- Education and special training can cut two ways. A line devoted to having attended safety school is well worth it. A line saying you've received cold weather training is a line wasted.

Resume Document

Whatever you do, do not submit your resume in its Word .doc form or any other native word processor format. These do not always read correctly on different computers, can be altered, and can cause the reader to simply give up. The one format just about everyone can read without fail is the Adobe .pdf format.

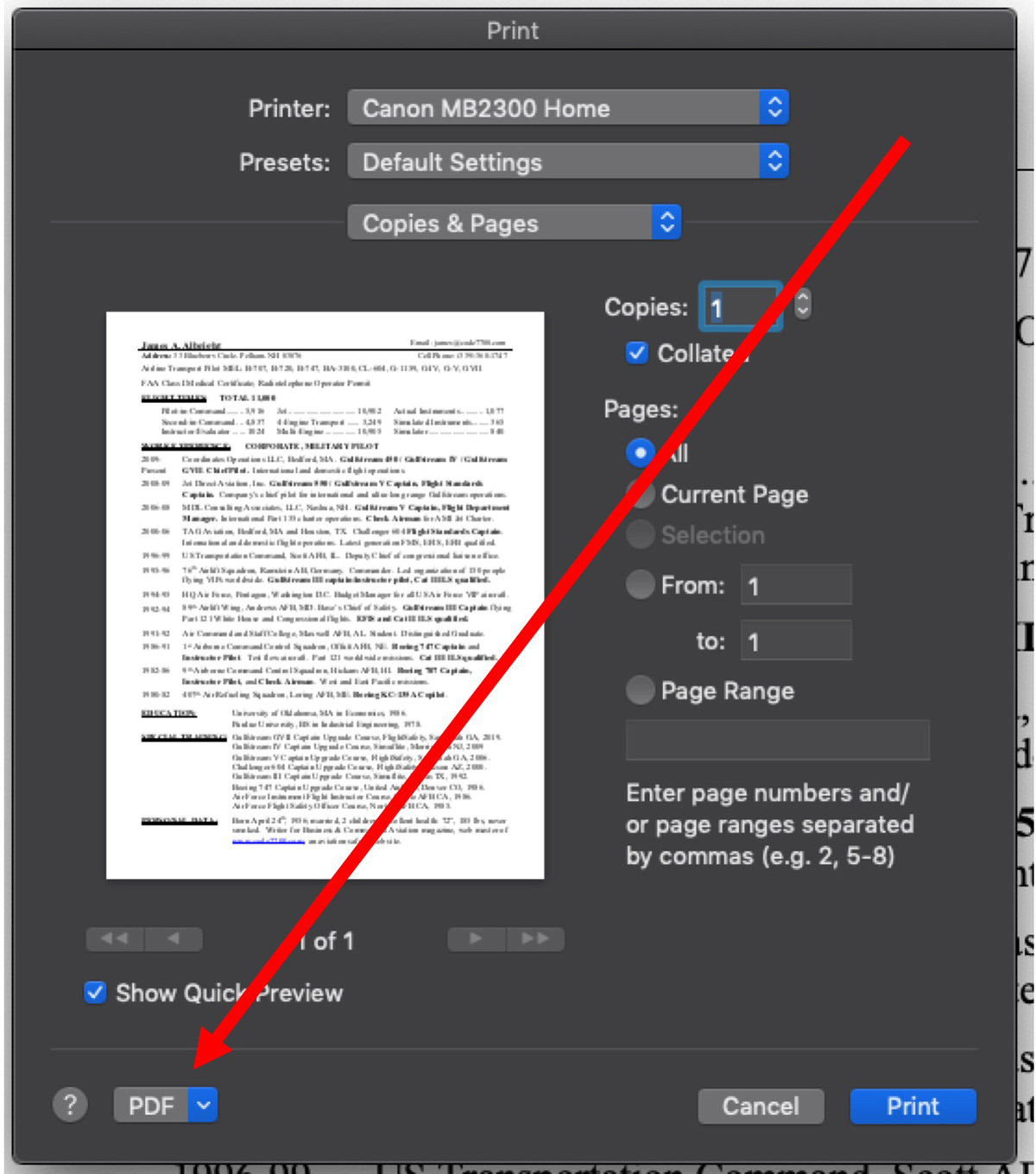

You can convert your word processor file to a PDF on a MacBook by selecting it from the print menu:

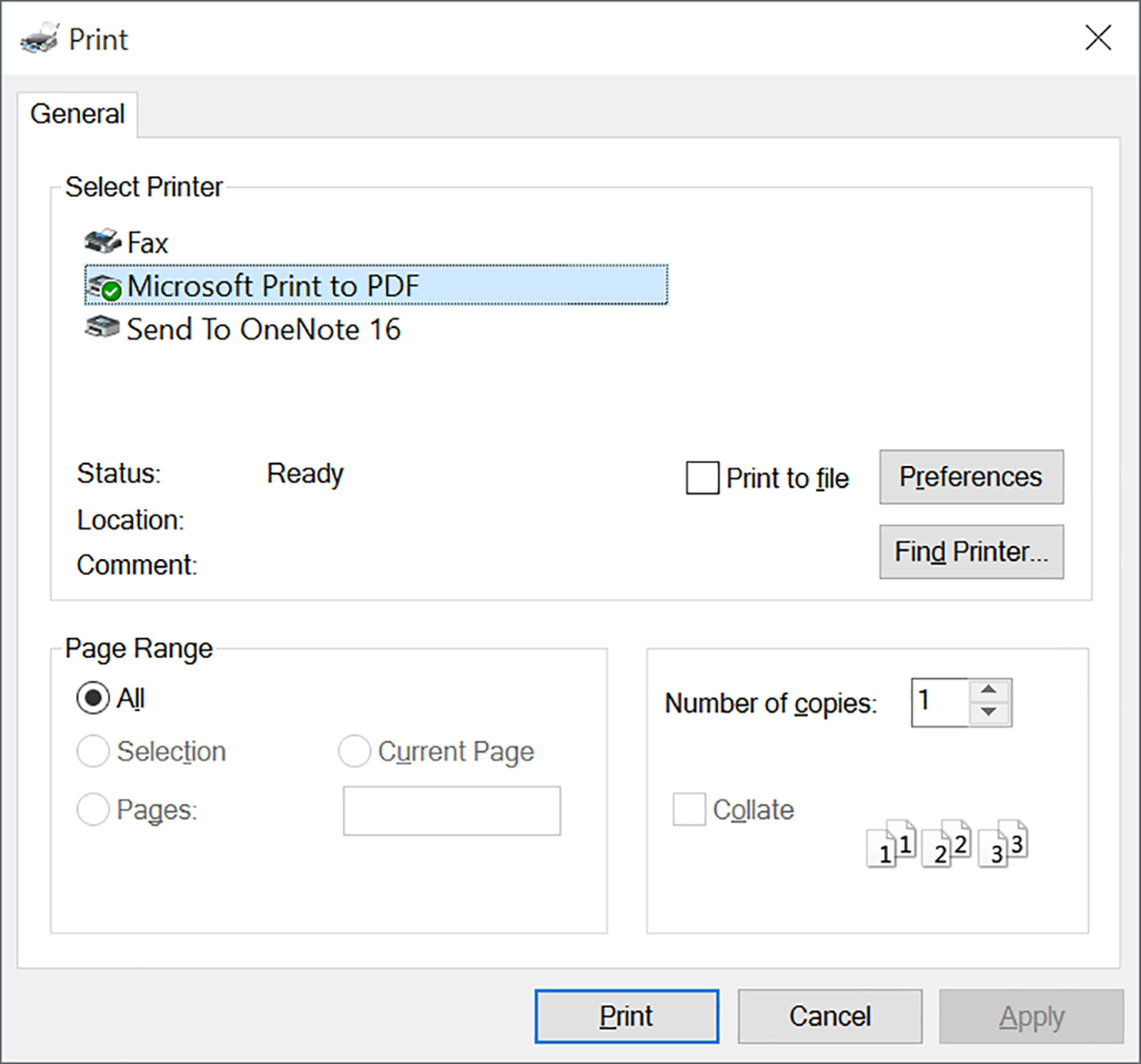

You can convert your word processor file to a PDF using Windows 10 by selecting it from the print menu:

If you are using an earlier version of Windows, you may have to download a PDF converter.

Resume Pitfalls

- Catch phrases. An overuse of popular catch phrases – think “Customer focus” and “Process Oriented”– can be a sign of a pilot with no real positive accomplishments. A better approach is a sentence or two demonstrating the catch phrase, not the catch phrase itself. “Wrote company Safety Management System manuals and led effort to achieve top SMS rating” speaks volumes; “safety first pilot” is a mere platitude.

- Jargon. A candidate who throws about arcane terminology is either a poor writer or someone with an inflated view of their own place in the world. Military pilots can be the worst offenders here. While those of us with Air Force backgrounds might know that a pilot with an “SCI” was granted special security access, most resume readers do not. And even those of us who know what Sensitive Compartmented Information is must wonder why that matters on a pilot’s resume. Civilians can also be offenders here. Many of us who manage international flight operations are acutely aware of “EU ETS” but don’t care to see that on a resume unless the pilot’s involvement with the European Union Emissions Trading System is something we are specifically seeking.

- “Pay for praise” services. Pilots who include references from well-known vanity publications that will say nice things about them for a price should be avoided. A membership to “Who’s Who in America,” the “Top 500 Leaders in Aviation,” or other similar organizations could be a tip that not only was the pilot duped into membership, but the pilot believes you are as gullible. There are also legitimate organizations that perform personality profiles that provide honest assessments of a candidate’s strengths, but they omit any weaknesses. We once received a resume with fifteen pages of such strengths. Further investigation revealed these were boiler plated strengths and the pages that were omitted were more revealing than those that were included.

- Unrealistic or inflated claims. How pilots write resumes provide windows into their personalities. A pilot who is tasked with performing annual routine maintenance checks who claims to be a test pilot, for example, may have an inflated and unrealistic confidence in his or her abilities. Another pilot who wrote on one line about “extensive international experience” but then bragged about “14 Atlantic Crossings” on another did not have the international “chops” we needed.

- Personal data or hobbies might be worth a line, but be careful. Speaking as someone who rides motorcycles, I don't like to see this on a resume. I don't want to hire someone who I think might end up on non-flying status for injuries.

10

How do I ace my interview?

The dirty little secret about job interviews is that hardly anyone knows how to do them effectively. While I was at the 89th Airlift Wing at Andrews AFB we had a week long interview process. Most of that time was wasted and meant more to initiate the candidates than to discover the best candidates. I think if you consider that the interview is your chance to learn about the company just as much as it is a chance show to off your strong points, you will have the right mindset. Don't let strange questions or odd situations throw you off. There is a good probability that the interviewer has less experience at that than you do at being interviewed.

Attitude: Humble

I've known pilots who come in with the attitude that they are "the best of the best" and that somehow worked for them. But that attitude is more likely to tell the interviewer that you are unwilling to learn from others and will be a divisive force if hired.

Being humble doesn't mean having an inferiority complex, it means realizing you will always have something to learn, you know that, and you embrace that.

Attitude: Confident

As an Air Force or Navy pilot, the training you received just to get your wings far surpasses anything your civilian counterparts have ever experienced. Years of having to balance mission with safety have also seasoned you in ways they can never hope to duplicate. You may be asked about things you've never heard about because you may not have had to deal with a broken lavatory cart, never had to use the latest generation of data link, or a long list of things you've never seen or heard about. But all that is trainable. What you have that is so much harder to obtain is the air sense that comes from years in an Air Force or Navy cockpit. So be confident that you are the right pilot for just about any job, but remember to be humble about that.

Attitude: Comfortable

I have been in the business of hiring pilots for a very long time, both in uniform and out. I quite often came away from an interview impressed or unimpressed, but not knowing why. In my current job I work for a CEO who has an intuitive sense about these things and was told about some of my more successful hires, "I liked him because he was comfortable in his own skin." The CEO turned down the applicant who was vying for the position I eventually got for the opposite reason. This particular pilot was also a "SAM Fox" pilot from the 89th. But the CEO said this pilot seemed unsure about everything: his history, his present, his future; everything. You should be able to answer a few questions easily, confidently, and comfortably:

- "What is it about flying airplanes keeps you flying airplanes?"

- "How has your time as an Air Force pilot shaped who you are?"

- "What is it you can offer us as a member of our team and what is it you hope to get from the experience?"

- "What are some of the biggest learning experiences you have taken away from years flying for the Air Force?"

If you struggle with any of these questions you might benefit from a "personal self assessment." You simply, and brutally, list all your strengths and weaknesses on paper. Then come up with a game plan for dealing with the weaknesses. You aren't going to show the list to anyone, this is just for you.

How to practice

I recommend you find someone with a little experience as an airline or corporate pilot and ask for a favor. Give them your resume and ask them for an hour of their time. Yes, an hour. Ask them to play the part of interviewer and ask that they formulate at least twenty questions taken from your resume. And then dress the part, show up, and answer those questions. You might consider recording or even taking a video. Then replay the tapes. We often "chair fly" important missions. This is an important mission. So chair fly it.

Bottom Line: Attitude

Did I mention attitude?

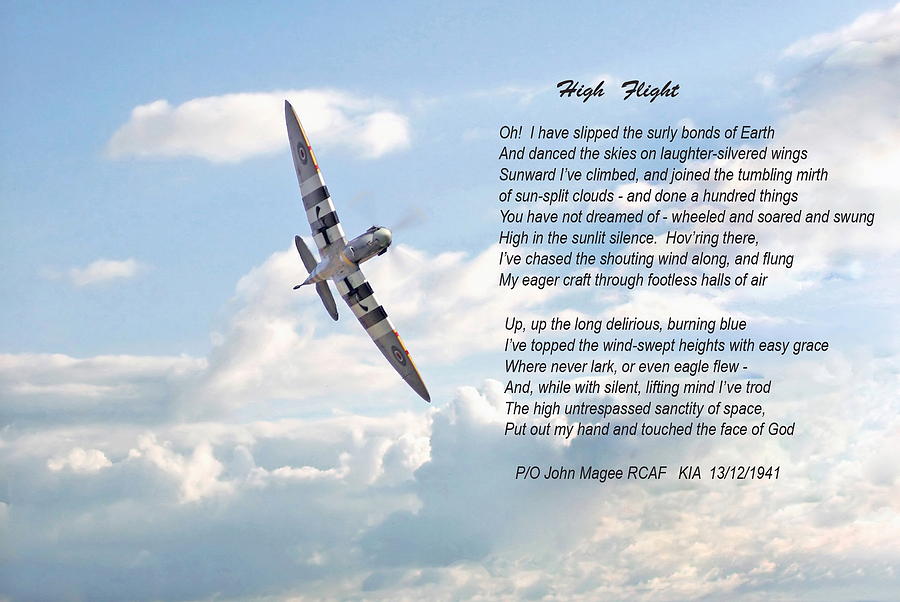

Be humble. You may have x-number of missions in combat, have flown supersonic, and as John Gillespie Magee, Jr. puts it, "touched the face of God." But you haven't done what we do, and you will have to learn.

Be confident. You outclass the competition. Your training is invaluable and that will show through. Realize that any airline or corporate operator will be benefit from hiring you.

Be comfortable. A nervous interviewee makes for a nervous interviewer. Run a personal assessment an be able to easily discuss your strengths and weaknesses.

Good luck.

Your view of corporate aviation could be colored one way or another based on limited information, just as you might not have an accurate view of the airlines or the regionals. Each of these parts of aviation are pretty diverse and you cannot assume everyone is the same as one particular anecdotal story. A reader provides an excellent point and has allowed me to post his email.

James,

I heard someone who returned to the U.S. after 4 years in China say something that stood out to me: “Everything is true. Everything, somewhere in China, is true.” Meaning it’s such a large country that everything you’ve heard is true, somewhere.

This got me thinking about corporate aviation; I believe the same can be said of us. Everything is true - all the good, all the bad, everything, somewhere, is true. And I think this is what makes our segment of the industry so difficult to nail down. There are so many operators, made up of so many different personalities and leadership styles and cultures that it’s impossible to accurately portray corporate aviation. It’s vast, it’s varied. Generalizations can be made, but it really comes down to the individuality of each operator. This is a weakness, but I also see it as a strength. In my experience, in corporate aviation, my work ethic, my approach to safety, my contribution directly affect the culture, the atmosphere, and the individuality of my department. I find satisfaction that my role, my contribution, directly influences the success of the department. I really don’t think I’d feel the same thing flying for an airline, being one of three thousand pilots.