Many pilots get their start at small, “uncontrolled” airports without towers and these airports are considered relatively easy. These kinds of pilots may grow anxious with the thought of having to talk to a tower controller or may elect to fly elsewhere if the airport includes more than one layer of air traffic control. Class B airspace? No way!

— James Albright

Updated:

2025-07-15

Those of us on the other side of the spectrum think nothing of flying at places famously known by a strange three-letter-code. ORD, LAX, BOS, JFK? No problems. But we don’t give enough deference to uncontrolled airports.

Yes, I know that the 2018 version of Advisory Circular 90-66A, “Non-towered airport flight operations,” banished the term “uncontrolled” airport. I suppose this was a good change but based on my many years flying out of these kinds of airports, I think the term “uncontrolled airport” did a better job of telegraphing to the pilot just how much of a challenge they are. If you are flying a high-speed jet out of an uncontrolled airport, you need to bring your “A game.” The pilots of JetBlue 1748, on January 22, 2022, failed to do that.

1 — Getting to the runway and off the ground

3 — The NTSB Probable Cause and Findings

Date: Jan 22, 2022

Time: 11:57 L

Type: Airbus A320-232

Operator: JetBlue Airways

Registration: N760JB

Aircraft fate: damaged, repaired

108 persons, no injuries

Departure Airport: Hayden-Yampa Valley Airport, CO (KHDN)

1

Getting to the runway and off the ground

The captain and first officer flew in that morning “dead head” on the same aircraft. Both were well qualified and experienced with the airline and the Airbus A320 type. They had clean training and evaluation records. It is unclear how much time they had operating out of Hayden, Colorado, but their airline did have special qualification training for it.

They were parked at the terminal, listening to the airport’s UNICOM frequency on one radio and Denver Center on the other. The weather was good, the winds were calm, and the conditions seemed to promise an uneventful flight back to Fort Lauderdale.

The captain was the Pilot Flying (PF), was 45 years old and had 15 years with JetBlue. He had 11,590 hours and had flown the last 10 years as an A320 captain. The first officer was the Pilot Monitoring (PM), was 40 years old and had 8 years with JetBlue. He had 3,307 hours total and had flown the last six years as an A320 first officer.

To really understand what happened to this crew on the way to coming very close to catastrophe, one need only follow the Cockpit Voice Recorder (CVR), which I’ll do with a few points along the way. For readability, here is the CVR decoder:

PF, PM JetBlue pilots

KA-1, KA-2 King Air pilots (appears to be the pilot and his wife in the other seat)

CTR Denver Center ATC

UNI HDN Unicom (On the Common Traffic Advisory Frequency, CTAF)

Engine Start

11:48:41 PM: “and hayden airport jeblue 1748, we’re pushing off the ramp for ten.”

11:48:46 KA-1: “hayden yampa valley king air three five zero juliet. we're about nine uh...uh minutes out for uh ten. coming in from the east. descending out of seventeen thousand. three five zero juliet.”

11:49:04 UNI: “three five zero juliet. hayden unicom we have multiple aircraft inbound. winds are calm. altimeter three zero three six.”

(NTSB DCA22LA069 CVR)

The King Air pilot says “ten” instead of “runway ten,” which the NTSB report correctly notes is non-standard.

Pushback and engine start are busy periods for the A320 crew. They were both evidently monitoring UNI and CTR. The PM and PF discussed the multiple airplanes, including the King Air, inbound using Runway 10. The PM also contacted Denver Center and confirmed their intent to depart on Runway 10.

11:50:53 The flight crew started engine 1.

11:51:55 KA-1: “Denver three five zero Juliet”

11:52:02 The flight crew started engine 2.

KA-1: “denver three five zero juliet.”

CTR: “five zero juliet go ahead.”

KA-1: “uhhh would it inconvenience you if we canceled and landed two eight? we can see the runway * * almost five hundred overcast.”

11:52:12 CTR: “it's up to you. if you want to cancel that's fine.”

KA-1: “all right. we're going to cancel right now and land two eight. hayden yampa valley.”

CTR: “five zero juliet cancellation received. squawk V-F-R. frequency change approved. have a good day.”

KA-2: “squawk V-F-R. over to * * as well. Five zero Juliet good day.

11:53:07 KA-1: “three five zero juliet's going to go ahead and land two eight. hayden yampa valley we're straight in. two eight right now.”

11:53:19 PM: “hayden yampa valley jetblue seventeen forty eight airbus coming off the ramp for runway one zero. hayden yampa valley.”

11:53:26 UNI: “jetblue seventeen forty eight hayden unicom we have multiple aircraft inbound. winds are currently calm. altimeter is three zero three six.”

PM: “roger. seventeen forty eight.”

11:53:42 The flight crew performed an after-start checklist.

(NTSB DCA22LA069 CVR)

Notice that in a span of just 3 minutes, the JetBlue crew started both engines and started the after-start checklist. In the same time, the King Air pilot changed his plan from “ten” to “two eight.” Should the JetBlue crew have noticed that? I think so, but they were busy.

11:53:45 KA-1: “three five zero juliet's uh...twelve mile final two eight straight in. hayden yampa valley.”

11:54:00 PM, “we’re number one [for departure], do you want to do anything else first?”

PF, “I think we’re going to wait for these planes to come in.”

The flight crew performed a flight control free and clear check.

(NTSB DCA22LA069 CVR)

In post-accident interviews, both JetBlue pilots indicated they were convinced the King Air was landing on Runway 10. At this point they would have been at the end of Runway 10, looking to their right for the traffic they though was landing on Runway 10. Depending on the TCAS range they had selected, it is unlikely the King Air would have appeared from its actual position on the other side of the airport.

Note also that the King Air pilot never uses the word “Runway” with the runway number. The NTSB report notes this, saying that “Runway Two Eight” might have gotten the Jet Blue’s attention better than “two eight.”

11:54:25 KA-1: “anybody about to depart uh ten at hayden?”

PF: “jetblue seventeen forty eight is uh...going to holding short of the runway. runway ten at the end of the runway waiting for our clearance.”

KA-1: “all right we're on a uh ten mile final two eight straight in.”

PF: “all right copy that. we'll keep an eye out for you.”

KA-1: “hayden yampa valley.”

PM, “all right so he’s coming in right now.”

(NTSB DCA22LA069 CVR)

This was another missed opportunity for the JetBlue crew. First, “final two eight straight in” should have alarmed them. Second, a ten mile final should have told them they would see the aircraft soon. (A King Air may have an approach speed near 2 miles a mile, so the airplane should be over the runway in about 5 minutes.) The JetBlue crew decides they can make it off the runway in less than that time.

11:54:48 The flight crew began the before-takeoff checklist. During the checklist, they verbalized speeds of 142 knots, 142 knots, and 143 knots.

PM: “denver jetblue seventeen forty eight number one at runway one zero ready for departure.”

CTR: “jetblue ready at hayden understood?”

PM: “affirmative. seventeen forty eight.”

The Denver center controller cleared the airplane to FLL as filed, with a 2-minute clearance void time.

CTR: “jetblue seventeen forty eight cleared from hayden to uh fort lauderdale as filed. climb and maintain one three thousand. squawk zero six two two. released. clearance void if not off in two minutes.”

(NTSB DCA22LA069 CVR)

The void time places a not-so-subtle pressure on the crew: “we need to go now!” I can see how this could have made them rationalized that the traffic ten miles out on Runway 10 wasn’t going to be a problem because . . . “we need to go now!”

PM: “all right roger that fort lauderdale as filed. one three thousand. squawk zero six two two. uh off in two minutes. jetblue seventeen forty eight.”

11:56:06 The flight crew performed a takeoff briefing and finished the before-takeoff checklist.

11:56:25 PM: “hayden traffic. jetblue seventeen forty eight uh released and we are taking off runway one zero.”

11:56:30 KA-1: “uh hayden yampa valley uh you got uh a king air on final two eight. hayden yampa valley. we've been calling.”

11:56:37 PM: “yeah I thought you guys were still like eight...nine miles out.”

KA-1: “four miles.”

KA-2: “less than that.”

(NTSB DCA22LA069 CVR)

Even if they were convinced the King Air was on a four mile final for Runway 10, they shouldn’t have thought a takeoff was a sane decision. At the very least, if they didn’t see the aircraft, they should have realized something was amiss. 11 seconds later:

11:56:48 PM: “and jetblue’s on the roll. jetblue uh seventeen forty eight on the roll runway one zero hayden.”

KA-1: “all right we're on a short final. I hope you don't hit us.”

(NTSB DCA22LA069 CVR)

Two huge problems here.

First, I would think the King Air pilot sees the JetBlue at this time. They are on final for the runway and should have a good view of it. Throughout what happens next, it seems the King Air pilot thinks he has no option but to continue. I’ve read from some pundits that if the King Air pilot went around, things would have been worse, since the JetBlue would rotate into them. I’ve been in the King Air pilot’s situation a few times and the thought of a go around wasn’t my preferred option. “I’m breaking off the approach and will join a right downwind. You can thank me later, JetBlue.”

Second, the King Air pilot’s phraseology was a red flag. “I hope you don’t hit me.” At this point the JetBlue was well below V1 and an abort was called for but never considered.

11:57:02 Sounds similar to an increase in engine thrust were noted.

11:57:06 PM, “airspeed’s alive.”

11:57:13 PM, “he’s [the King Air] on two eight?”

PF, “is he? oh #.”

PM, “eighty knots power set."

11:57:19 PM, “yes he [the King Air] is on two eight. do you see him?”

PF, “no.”

11:57:23 KA-1: “you guys do a quick uh turn out cause we're [cut off by another radio transmission].”

(NTSB DCA22LA069 CVR)

In these 21 seconds, the JetBlue was still below V1 and two things should have happened. The JetBlue should have aborted and the King Air should have gone around. It is as if the pilots on both aircraft were locked into their planned actions. The JetBlue PF does something completely unexpected: he rotates 24 knots early.

11:57:25 PF, “oh jesus christ.”

PM, “you’re slow. airspeed. airspeed. airspeed. airspeed.”

Sounds similar to a tail strike were noted immediately thereafter.

(NTSB DCA22LA069 CVR)

2

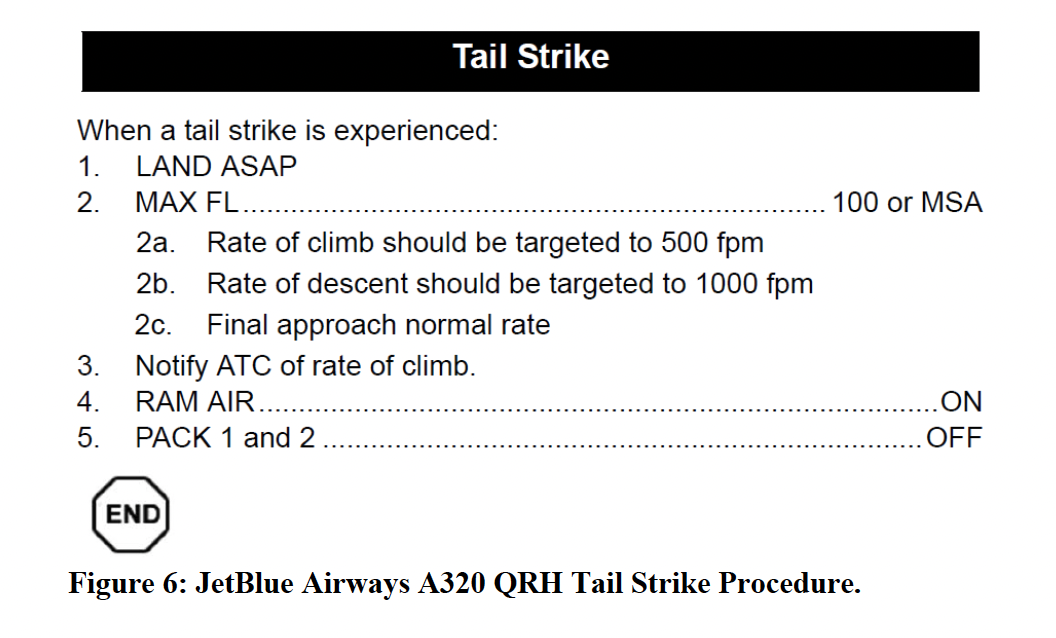

Tail strike

A post-accident interview of the captain makes it appear that the airplane had a mind of its own:

In an effort to avoid conflicting traffic and while I am actively trying to acquire the inbound plane, the aircraft’s nose starts to pitch up, and a potential tail strike on the runway occurs. I lowered the pitch of the nose, continued with the takeoff / rotation.

(Captain’s statement (Op Factors, pp. 20-21)

The captain managed to get the airplane into the air, gain speed, and make the turn.

11:57:32 PM, “positive rate.”

PF, “what the # was that?”

PM, “I think it- it may have been the tail.”

(NTSB DCA22LA069 CVR)

The tail strike was so hard, a flight attendant contacted the crew and said the passengers were concerned.

The crew elected to continue and contacted Denver Center and climbed to 13,000 ft, with further clearances to FL230 at time 12:02:22. Four minutes later, the PF contacted a maintenance controller to discuss “the hard impact” on departure.

At 12:09:39 the crew was cleared to FL310 and two minutes later to FL350.

At 12:11:35 the maintenance controller recommended they not continue to FLL and land the airplane. The PF agreed to diverting to DEN.

(NTSB DCA22LA069 CVR)

I’ve never had a tail strike, but a few things come to mind. First, the structural integrity of the aircraft is in question, and it may not be a good idea to clean up and accelerate. If the flaps come up, will they come down again? Second, even if the aircraft pressurizes normally at low altitude, as the differential pressure increases with altitude, will the pressure vessel remain intact? The crew never considered the tail strike checklist, which would have been a great thing to do at this point:

As the crew continued to Denver, they had a moment to reflect:

12:22:21 PF, “this is one of those moments where like- you know- when- you got so much # going on ya know you’re just seeing what you need to do you know to save yourself you know what I mean? and so you make- like you- you don’t know like is this guy coming at me? is he on the downwind? ya know? so had- had we said reject-“

PM, “I should’ve just- I should’ve just # said stop. I knew I- I put it all together like coming- I don’t know how fast we were going but…”

PF, “yeah well we were- that was the other problem we were like right there at V one. I just- I just reacted too quickly.”

PM, “yeah we were- we were slow. really slow.”

PF, “yeah I wanted to get off the ground ya know?”

(NTSB DCA22LA069 CVR)

3

The NTSB Probable Cause and Findings

The National Transportation Safety Board determines the probable cause(s) of this accident to be:

The captain’s rotation of the airplane pitch before the rotation speed on takeoff due to his surprise about encountering head on landing traffic, which resulted in an exceedance of the airplane’s pitch limit and a subsequent tail strike.

Contributing to the accident was the flight crew’s expectation bias that the incoming aircraft was landing on the same runway as they were departing from, and the conflicting traffic’s nonstandard use of phraseology when making position calls on the common traffic advisory frequency.

Final Report, NTSB DCA22LA069

4

My concerns

First, once again, the NTSB tells us what happened but now why. You could argue the why is “expectation bias.” I would argue that the pilots had expectation bias because the airline world has drilled into them the need for speed. As I say in my article, Being a Better Pilot, Rule 1 for being a better pilot is “don’t get busy.” If you ever feel you have to rush, you’ve already made a mistake and it may be time to reconsider what you are doing.

Second, these pilots failed to address the tail strike before it could have become catastrophic. There are a few Crew Resource Management philosophies on this matter, though I’m not sure how useful they are. I’ll cover three, my thoughts about them, and another idea. The idea is that when you are presented with an emergency situation, use these ideas to help your decision making.

FORDEC

F – Facts: Gather and assess all relevant information (weather, aircraft systems, fuel state, ATC info, etc.).

O – Options: Identify all possible courses of action.

R – Risks and Benefits: Evaluate the pros and cons of each option.

D – Decision: Choose the best option based on the facts and assessment.

E – Execute: Put the chosen course of action into effect.

C – Check: Monitor the outcome and reassess if necessary (is it working? Do we need to revise the plan?).

PIOSSEE

P – Problem: Identify what’s wrong (e.g., engine failure, abnormal indications).

I – Immediate Action: Perform any critical emergency memory items or boldface procedures that must be done without delay.

O – Options: Consider all feasible courses of action (e.g., divert, eject, continue, troubleshoot).

S – Select: Choose the best available option based on the situation.

S – Start Execution: Begin carrying out the selected course of action.

E – Evaluate: Continuously monitor the results and adjust as needed.

E – Execute Backup Plan (sometimes interpreted as a second evaluation or finalize execution depending on training context).

DECIDE

D – Detect the change

E – Estimate the need to react

C – Choose a desirable outcome

I – Identify actions to control the change

D – Do the necessary action

E – Evaluate the effect

Another idea

If one of these acronyms works for you, then you should use them. But I would caution you about the first step, be it gathering facts, identifying the problem, or detecting any changes. While I don’t consciously employ John Boyd’s OODA Loop in these situations, the first two O’s are key:

O – Observe

O – Orient

D – Decide

A – Act.

When faced with a situation, it is vitally important to take stock about what has happened – Observe using all available means – and figure out how that relates to your current situation – Orient yourself – before taking action.

Every pilot in this incident – both JetBlue pilots and the King Air pilot – failed to do as well as they should have. For some strange reason, the NTSB Operational Factors report spends time on FAR 91.13 careless or reckless operation, but doesn’t explain why. I don’t think these pilots were reckless or careless. But I do think they were inept.

References

(Source material)

Aviation Investigation Final Report, Tail strike, Hayden, Colorado, DCA22LA069, January 22, 2022

Specialist’s Factual Report, Cockpit Voice Recorder, DCA22LA069, NTSB, December 11, 2023

Specialist’s Factual Report, Operational Factors, DCA22LA069, NTSB, February 16, 2022