A few reasons to panic. First, you've been named your flight department's new director of safety and you've never done that before. Now what if your flight department has never had a safety program before? Or, even more concerning, you find out you need an SMS and you don't even know how to spell SMS? Well, panic not. This is all within your grasp.

— James Albright

Updated:

2024-07-15

The good news is that being a safety officer broadens your horizons and will, believe it or not, make you a better professional. I was fortunate to have my first stint as a safety officer at the ripe old age of 27, just 5 years into my flying career. It made me look at everything to do with flight with a new perspective. A better perspective. I've seen this metamorphosis take place in others. I wish you luck on this journey.

1 — What is your purpose? Do you really need a purpose?

2 — Where do you fit in the organization? How to fix that if it is wrong?

3 — Does the organization have an established safety program? How do you start one from scratch?

4 — Does the organization have an established SMS program? How do you start one from scratch?

5 — Finding safety issues and fixing them

7 — The all-important regular safety meeting

8 — Turning everyone in the organization into safety officers

Appendix — A basic safety manual (in case you don't have one)

1

What is your purpose?

Do you really need a purpose?

The bottom line on top

As trite as it may sound, a safety officer's purpose is to make everything safer. But isn't that an overly broad statement? Sure. Even breaking it down into parts still leaves you with a lot to consider. You exist to ensure policies, procedures, training, and oversight all support this overarching goal of safety. That means your business encompasses everyone's business. You have to be interested in every step leading to the actual flying (acquisition of aircraft and support gear, maintenance of that gear, training and planning), the actual flying, and the postflight considerations. It would be easy enough to limit your scope to only cover those things that go wrong, but that approach only leads to things going wrong. A true safety officer is proactive as well a reactive.

The secret to being successful

I've held the title of safety officer twice, both times in the Air Force. I've appointed safety officers many times, both in the Air Force and as a civilian flight department manager. The most common approach to being a safety officer is to keep your head low to avoid extra work, wait for bad things to happen, throw just enough paperwork at the bad thing as needed to make it go away, and try to survive until another job appears. These safety officers earned reputations for being ineffectual and were usually the last to be chosen when something needs to get solved.

I managed to escape that tendency because one of the safety officers who preceded my first time at bat was a charismatic instructor pilot who was overqualified for every job that came his way. Let's call him "The Nick," because that's what he called himself. He only lasted a year as a safety officer because the talents he displayed as a safety officer were in high demand. I'll cover one of his exploits below, when talking about Safety meetings. The Nick taught me the importance of enthusiasm. For him, and for me, there was no duty more important to the organization than that of safety officer. The squadron commander knew The Nick was busy, but kept picking him for special projects because he knew they would be handled expertly. Within a year The Nick got hired away and another pilot took his place. That pilot lasted a year and I followed. After a little less than a year, I was hired away. If you are doing your job as a safety officer, it isn't long before everyone knows who you are.

2

Where do you fit in the organization?

How to fix that if it is wrong?

In theory

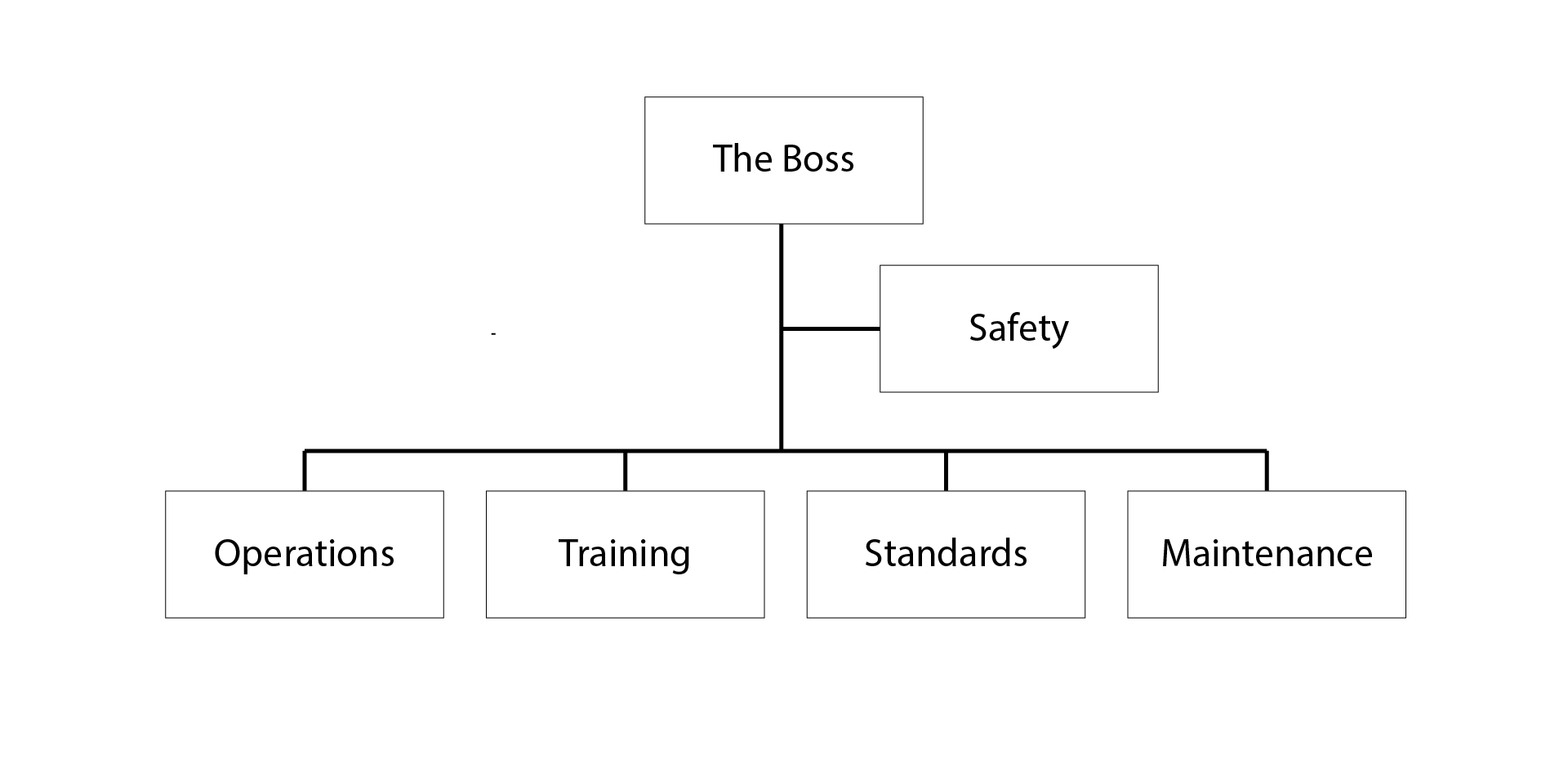

In a typical flying organization you have one person in charge, let's call him "The Boss" but he or she could go by "Chief Pilot," "Director of Aviation," "Flight Department Manager," or something equivalent. That person is charged with getting the flight operation headed in the right direction and doing the job at hand. Under that person you may have other people in charge of operations, training, standardization, maintenance, and other tasks. The Boss may wear several hats and could handle some or all of these tasks. For our purposes, let's assume we have at least the boss, a person in charge of other things, and a safety officer. Of vital importance here is that the safety officer reports directly to the boss.

When I was the 89th Airlift Wing's Chief of Safety back in 1994, I sat on the wing commander's staff comprised of seven group commanders, all colonels, and me. I was a major, certainly the lowest ranking officer on the staff. When I had an issue to pursue with flight operations, for example, I would attempt to resolve any problems with members of the Operations Group first, followed by dealing directly with the Operations Group Commander. If that came to no avail, I had direct access to the wing commander himself; not jumping the chain of command since the organization was designed to give me that access.

In practice

Many organizations place layers between the troops and the boss according to seniority, established friendships, "how it has always been done," or other arrangements. Since the safety officer may have been selected from the bottom ranks of seniority, friendships, or other ideas, the safety officer might not have unfettered access to the boss.

One of the most controversial issues I faced at Andrews was one of the squadron's insistence on flying some of their aircraft overweight. The U.S. Secretary of State and some of the more influential U.S. Senators would fly on our Boeing 707s, of which we had four 707-300 models and three smaller 707-200 models. As designed, the -200s carried less fuel and had less range. As the wing's chief of safety, I had a staff of ten, including one member from each of the flying squadrons. I asked each member to tell me what worried them at night. The pilot from the 707 squadron said it was the practice of flying the -200s overweight by nearly 20,000 lbs. After investigating, I found the squadron applied for a waiver from Boeing after taking delivery of the aircraft, twenty years earlier. They used the waiver application to justify flying overweight, but nobody could produce anything from Boeing approving the practice. I called the Boeing office responsible for such things and they produced a letter denying the application. They told me flying overweight as we were doing was dangerous. I went through the squadron and operations staff and was told each step of the way that they would not change the practice because the mission was too important. They made a point of the fact we had been flying the airplane this way for twenty years and nothing bad had happened. Besides, they argued, if we suddenly decreased the range of the airplane, the White House would be furious. I next went over the squadron and brought up the subject at one of the wing commander's staff meetings. I let the Operations Group Commander know that I was going to do this and he was prepared to do battle. He said that he called Boeing personally and was reassured we were okay.

Making it work the way it is supposed to

As with many jobs of any level of importance, the art behind the science of this job rests on the power of persuasion. If you don't have a formal pipeline to the boss, it is up to you to develop an informal connection. You can do that in social settings or on the job by becoming someone the boss is comfortable talking to. If the boss is secluded and protected by a staff of handlers who keep him or her at arm's length, you then need to develop this same relationship with those handlers. They are charged with protecting the boss; you need to make them understand that is your goal as well.

After the meeting I asked the Operations Group Commander who at Boeing he spoke to. The colonel told me he didn't have time to deal with me and he considered the case closed. I went back to the Boeing engineer I spoke to earlier, and asked for something in writing signed by a VP or higher. The engineer came through in just a few days. I took this to the wing commander and said I was worried that if we ended up crashing an airplane with the Vice President on board, Boeing wouldn't be shy in saying we were operating the airplane outside of their published limitations. That's all the wing commander needed to hear. The White House protested but when told this was an aircraft limitation, they back down immediately. The squadron was furious and predicted an end to my career at Andrews. At the next promotion board, the wing commander endorsed me and I was promoted to lieutenant colonel.

3

Does the organization have an established safety program?

How do you start one from scratch?

Yes, we already have an established safety program

Just as every organization’s flight operations will be unique, each safety program will be tailored to that organization. In general, however, each safety program should have a few things in common.

- The safety program should have a written charter. This could be as simple as a few paragraphs in the flight department's operations manual or as extensive as a dedicated manual.

- The safety program should have personnel assigned to administer the program. In small flight departments this can be a single person.

- The goal of the safety program should be to prevent personal injury and losses resulting from accidents and incidents related to the organization’s business.

- The structure and staffing of the safety function should be formally recognized within the organization.

If you have an established safety program, your first step should be to talk with the previous safety officer to understand the duties, priorities, and any challenges you will be faced with. Second, research the existing flight operations manual and any organization-specific material about your new position. Finally, make sure to have a long conversation with the flight department's boss to learn what the organization expects of you and to get a feel for just how seriously the organization prioritizes the safety function.

No, we don't have an established safety program

Your first step when starting a safety program from the ground up is an honest assessment of everything. You need to assess the people, the operation, yourself, and any existing operating manuals.

Assessing the people situation starts at the top. Is the boss receptive to the idea of a dedicated safety function that could find fault within the organization? If not, you may need to structure any action with a positive spin. If, for example, you notice that electrical extension cords strewn across the hangar floor present a trip hazard, you can approach the need to reroute or cover these as a way of avoiding physical injuries and potential healthcare costs. It may be helpful to avoid framing it as, "Fred is being unsafe," or "we have a safety issue." Instead, try, "I think it would be safer and more efficient to use extension cord covers."

Assessing the operation itself requires a dispassionate view of day-to-day operations with a view of identifying hazards and potential ways to improve safety practices. This often leads to the idea of "we've always done it that way." The correct response to that is, "Why has it always been done that way?"

Assessing yourself means you need to measure your own strengths and weaknesses. A good safety officer should be knowledgeable about all areas of the operation, should be tactful when dealing with others, should be approachable, and should be unafraid to challenge the status quo.

Your flight operation should have an operations manual, often called a Flight Operations Manual (FOM), Company Operations Manual (COM), or something equivalent. Your safety program should be included. If not, I've included a Microsoft Word template for a simple manual below, in the Appendix. Writing your own manual, or adapting someone else's manual to fit your operation, is a great way to start the process of inventing a brand new safety program. Before you begin, however, consider starting with a Safety Management System (SMS) as a way of starting a safety program. If you are a domestic Part 91 operator, an SMS might be optional. Otherwise you will need an SMS program. Mandatory or not, even a minimal SMS will serve you well.

Training

Unfortunately, most organizations train safety officers "in house," with informal lessons provided by people who have had the job before or simply handing over the existing manuals (if any). Lacking these, it may be helpful to seek out the advice of safety officers you know, or reach out to forums. A few helpful sources:

- College courses

- Formal courses from private institutions

- Organization-specific programs

- National Business Aviation Association (NBAA)

A few colleges offer formal courses in aviation safety designed for flight safety officers. The Air Force sent me to an excellent course hosted by the University of Southern California (USC). Many other colleges with aviation programs have formal degrees in aviation safety but may also offer the chance to attend specific courses in person or on line. A few good choices: Purdue University (West Lafayette, IN), University of North Dakota (Grand Forks, ND), Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University (Daytona Beach, FL), University of Oklahoma (Norman, OK), and Ohio State University (Columbus, OH)

There are organizations dedicated to safety officer training, such as the Southern California Safety Institute (SCSI). These schools are designed to get safety officers up to speed quickly and provide resources for further career development.

Large organizations may have dedicated flight safety officer training programs or access to these hosted by other organizations. If your department is in any way connected to the U.S. government, for example, you might be eligible for the FAA Safety Officer Training Course. Even if you think your particular company is too small for such a program, you might have access to a sister company's program.

You might consider the NBAA Safety Manager Certificate Program. It is an online program that will take six weeks to complete, though you are given six months to structure the program to your schedule. The cost is $275 for NBAA members, $350 for non-members.

Many formal courses designed to teach flight safety officers all they need to know are incorporated into Safety Management System (SMS) programs. With or without an established safety program, you need to learn SMS to become an effective safety officer.

4

Does the organization have an established SMS program?

How do you start one from scratch?

What is an SMS program and how it is different from a "safety program?"

The key to understanding what makes up a Safety Management System (SMS) is the last word: system. An SMS isn't a subset of your flight operations, it is embedded within every facet of the operation. A safety program, on the other hand, is how we used to think of our efforts to make things safer.

An SMS is built around your safety policy, safety risk management, safety assurance, and safety promotion:

- A safety policy is where the organization sets its Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) and management conveys its commitment to the safety program. This is typically done in a flight operations manual or other written document that provides easy access to every member of the organization. If you don’t have such a document, you can start with the SOPs in your aircraft manual and a letter from the company that basically says you will follow those, and the company will employ a policy that encourages all members to report any safety issues.

- A safety risk management program provides a mechanism for people to report potential problems and for the organization to mitigate those problems in a collaborative process. It can be as simple as a blank form or an email to the safety officer, followed by one or more people coming up with a fix.

- Safety assurance is a way to monitor and measure how things are going, including those things that have been addressed by the safety risk management program. In short, it answers the question, “did our fixes work?”

- Safety promotion lets everyone know that they are a part of the SMS, the organization’s safety priority, reporting procedures, and how risks are mitigated. It should involve regular training and participation.

Sounds complicated? I guess it really is. But you don't have to do it all immediately. If fact, SMS never really ends. There isn't an end point to SMS, at which time put it on the shelf and consider it done. But once you have an SMS in place, it will really make your operation more efficient and safer.

Yes, we have an SMS

If your operation already has an SMS, your task is made much easier. Follow the Yes, we already have an established safety program guidelines given above. Your next hurdle is to get trained. See my previous article, An SMS Primer / Getting Started.

No, we don't have an SMS

If you don't have an SMS, you need one. You can do this completely "in house" at no extra cost, but I do recommend seeking a vendor who can ease your way. My previous article, An SMS Primer, will get you started.

5

Finding safety issues and fixing them

Safety Management Strategy

As the manual provided below details, the first step in finding safety issues is to self-assess the operation itself. It is easy to approach this problem with the attitude, "We haven't had any problems so far," and dismiss the exercise. But you need to approach this dispassionately, as if you are an outsider looking at the operation for the first time.

I once flew a Gulfstream GV from a small airport; when I joined the flight department, they had already been in operation for nearly ten years. What could possibly go wrong? In the next year I discovered that we routinely exceeded the runway's Pavement Classification Number (PCN), the tower was often closed during our nighttime arrivals and we didn't have established procedures for determining the runway's condition, we didn't have an established way of measuring or mitigating crew fatigue, and we didn't have any kind of aircraft fire coverage other than the local town fire department which had no airport or aircraft training. We eventually came up with plans to mitigate each of these risks, but when I say eventually I mean it took years. A good SMS, which we didn't have, might have sped our process.

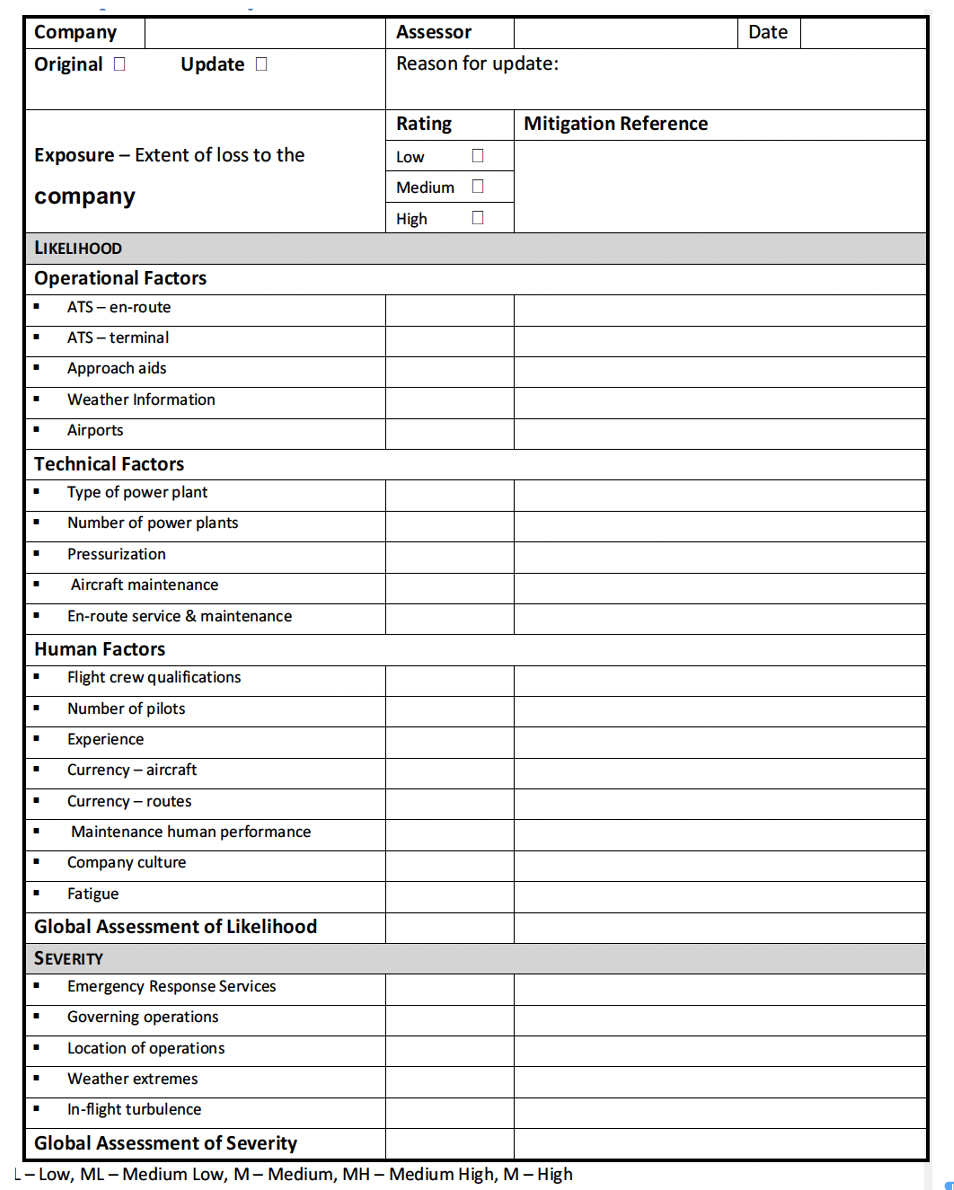

A good way to do an overall assessment like this is with a safety management strategy form. We use this anytime we have a major change, such as personnel or aircraft changes. It is a good way to remind you of some of the issues that should concern you. Here is a Microsoft Word form you can customize as your own: Safety Management Strategy.

Hazard Identification and Tracking

A classic idea from early safety programs is to simply hang a box with a stack of forms that anyone can fill out to report what they think is a potential hazard. This is also a staple of a good SMS program. Here is a sample form you can customize as your own: Hazard Identification and Tracking Form.

6

Soliciting safety ideas

The proverbial "open door"

The best sources of safety ideas will come from the pilots, flight attendants, mechanics, and other personnel who are "out there" doing their jobs. In an ideal world, they will feel completely comfortable approaching you with any ideas and concerns. You can help encourage that communication if you develop a reputation for openness, friendliness, and competence. Openness means they know you are always willing to listen. Friendliness lets them know you will be receptive and will not shutdown ideas that for some reason may not work out. Competence? You need to have a reputation for competence so they will feel assured you can get something done.

Continuous Improvement Opportunity — "The Suggestion Box"

Some of the best ideas in your organization may come from the least likely sources, viewed from a certain point of view. But what better source than someone out there doing the job, experiencing the frustrations and brain storming of a better way? You should let the troops know that all ideas will be entertained and doing so is as easy as filling out a form: Continuous Improvement Opportunity.

7

The all-important regular safety meeting

Getting their attention

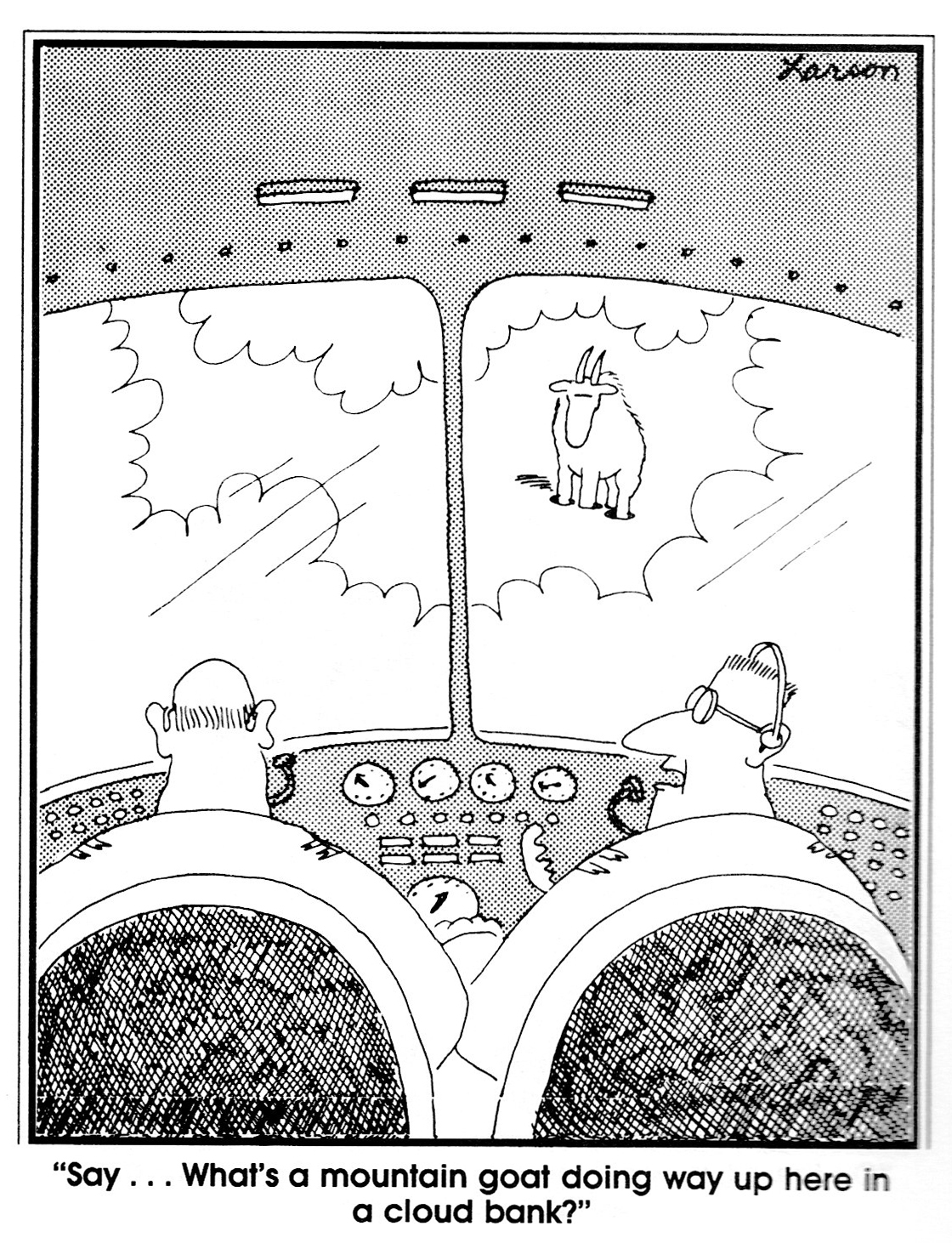

Back in 1982, the safety officer in my Hawaii squadron announced upcoming safety meetings with a photocopy of a Gary Larson cartoon doctored to fit the topic of the day. One month, when the topic was Controlled Flight Into Terrain, he used this cartoon without edits. This safety officer was "The Nick," whom you might remember from his starring role in Leadership 101. His meetings were usually fun while being informative.

Keeping their attention

For The Nick's final performance his posters announced "The Most Earth Shattering News in Safety, Ever!" He never gave the slightest clue what that news was. We all filed into the auditorium. There were about a hundred of us in the squadron and every seat was filled. A projector beamed a large U.S. flag onto the stage. At the appointed hour . . . no The Nick to be seen. We buzzed with anticipation. First, something about The Nick. He was a big man. He was as big as you could be as an Air Force captain without being in perpetual trouble with the Air Force Weight Control Program, something we called the "Fat Boy" program. Now, back to our story. A tape recorder piped into our meager sound system started up with a click. The sound of a bugle filled the room. And then on came The Nick, dressed as General Patton, complete with three stars and a chest full of fake ribbons. His speech was taken from the opening scene in the movie Patton and was hilarious. The news? The Nick was moving to a new position in the squadron and this would be his last meeting as our safety officer. Chris Manno, the artist who adorns many of the pages on this website, was named to take his place.

Keeping it relevant

Chris had an advantage over The Nick because he could draw his own cartoons. While he wasn't The Nick's equal for theatrics, his safety meetings were always relevant to something that happened in our airplanes. In short, you never felt like it was an hour of your life wasted. Chris left for the airlines and I took his place. I couldn't draw like Chris and I didn't have comedic talent like The Nick. But I could keep it relevant.

If I had a forte, it was the ability to enrage our leadership. We had, for example, an engine shutdown procedure that required us to run up the engine for 30 seconds before cutting it off. It was a holdover from the KC-135A which had a different engine P&D (Pressurization and Dump) valve than our EC-135Js. The procedure was loud and unexpected, an invitation for bad things to happen. Squadron leadership was adamant that the procedure must be followed, unless we had a dignitary on board being met by the news media or someone else deemed important. My topic for the month was not carrying over old procedures from old airplanes and I included a diagram of the KC-135A's engine, the reason for the run up, and a diagram of our engine showing we had a different P&D valve which made the run up unnecessary. I got called into the commander's office for a "talking to" about the chain of command. The next day the run up procedure was dropped and my next safety meeting was packed, standing room only.

A few pointers

You don't need to have stand up comedian or cartoonist skills to run good safety meetings; you just need to keep it relevant and interesting for your audience. I held my flight safety officer position for less than a year because I got hired away to run the wing's standardization office. Many years later I became the 89th Airlift Wing's Chief of Safety where I had a staff of flight safety officers who conducted the meetings. From all of this, I've learned a few things:

- Keep it short

- Keep it relevant

- Have something for everyone

- Be conversational

- Nervous? Practice!

- Don't take yourself too seriously

One of our wing commanders in Hawaii had a rule: "If you can't say it in an hour, you can't say it." He would walk out of meetings at the one hour point. Unless you are showing a film or have a guest speaker, I don't think anything over 30 minutes will hold most people's interest.

As much as a current aircraft accident interests you, if it doesn't pertain to the audience you will have a difficult time keeping everyone's interest. If you fly business jets, for example, talking F-14 carrier landings will be a hard sell. But talking about an F-22 near disaster because of a software glitch that made crossing the International Date Line a problem might be engaging and is certainly relevant. (See Aircraft Reliability/The exceptions we don't know about for more about that.)

If your audience includes more than pilots, you should include topics that will interest the non-pilots. That doesn't mean you should exclude pilot-only topics, but you should throw in a few things for the rest of the audience. I learned this early on when the most important topic of the day involved a performance problem we were having with the jet. Better said: a lack of performance problem. The topic was very big so that was my only topic for the day. The pilots, engineers, and navigators paid careful attention. As I was speaking I could see a few eyes glaze over but it was too late, I was committed. After my customary "any questions?" finale, our top flight steward stood and said, "What does any of this have to do with the flight stew?" earning a round of applause from the flight stewards and radio operators.

You will likely be speaking to people you know so it doesn't make sense to use someone else's vocabulary or speaking style: just be yourself. That will make the audience comfortable, which in turn will make you comfortable. A safety officer I had known for years tended to go over the top during his briefings. He always started with a quote from an historic figure and usually threw in a few words that didn't seem right and usually caused me to jot them down so I could look them up later. Visiting his office I found a copy of "Bartlett's Book of Familiar Quotes" on his desk, explaining that quirk of his. As for the vocabulary, he often misused the words. The irony in all this was that he was a good story teller at the bar.

I once saw a speaker freeze on stage while talking about a subject he was so knowledgeable about, he had written a book that was widely acclaimed as the best on that topic. The audience at first sat in stunned silence and then tried very hard to be polite and help the speaker get to the end. I talked to him after the event and he said this happens to him whenever he is on stage. I recommended he write out a word-for-word script, practice that, and be prepared to read the script if he found himself close to freezing up again. He said that would never work because audiences hate seeing the speaker read from a script. True enough, but that is much better than watching a speaking choking up, near tears, because of nervousness. After hundreds of times on stage I still do this. I almost never refer to the script, but having it as a crutch to rely on if I need it makes everything easier for me. When I practice, I break the speech up into one or two minute bites, and then I practice, practice, practice.

You are giving the briefing, they must think you know what you are talking about! It may seem that is what the audience expects of you. I have been a "key note speaker" a few times, been called "the smartest guy out there about ____," and in the strangest intro of my speaking career, "the money shot." All of these thoughts are destructive when it comes to approaching your time on stage with the proper sense of humility. You have something to say, that's true. But as vast as your knowledge may be, it isn't complete. Be prepared to find out you may be wrong about something, admit that, and promise to get smarter about it. When the lead flight steward called me out with, "What does any of this have to do with the flight stew?" quip, I laughed along with the audience and promised the next meeting would be more inclusive.

Note: at the time all our flight attendants were called flight stewards and stewardesses, a year later they became flight attendants, a year after that "Inflight Passenger Service Specialists."

8

Turning everyone in the organization into safety officers.

One of the many things that makes a Safety Management System better than a simple safety program is that a good SMS encourages everyone in the organization to think safety. Your objective is to encourage everyone to think about better ways of doing things; better means more efficient, less wasteful, more repeatable, less risky. In other words: safer. You can further that effort by receiving all ideas positively, pursuing them as best you can, and then giving credit to the person who first pushed it. One success leads to the next.

In one of my Gulfstream flight departments, we provided each member with yet another piece of paper to carry that included the high points of our Emergency Response Plan. As soon as we adopted it, I realized the paper would be lost and struggled to come up with a solution. (This was before we had smart phones.) Our hangar technician — the guy who washed the airplane and hangar floor — suggested we summarize only the most important part of the ERP on the back of a phone recall list everyone already carried in their wallets. Our safety officer advised him to submit a Continuous Improvement Opportunity form. At our next SMS audit, I cited this CIO as one of the most useful we had ever received. The auditor cited the hangar technician by name. From that point on, we had no shortage of CIOs. We had gone from one safety officer to many.

9

What’s next for you?

The best safety officers are those that feel a passion for making everything and everyone safer. The worst safety officers are those who are biding their time, waiting for something better to come their way. In either case, something will be coming their way. The best safety officers tend to be recognized as the people with good ideas and the drive to see those ideas through. As such, they are often plucked from their positions into others where the organization sees a need for that kind of talent. The worst safety officers are also recognized as such. A smart organization will soon replace them with someone who shows more potential. If it seems most organizations are using the safety officer position as a testing ground for future leadership, I suppose that is true. It is up to you to make the most of that opportunity.

Appendix

A basic safety manual

(in case you don't have one)

I've written a few of these "Flight Operations Manuals" over the years and after getting many requests for more, settled on a "boiler plate" of sorts that can be adapted as needed. This manual is written in Microsoft Word for easy adaptability. I've used the unimaginative title of "Acme Corp" which you can simply do a global find and replace to make your own. Some of the manual is tailored for the Gulfstream G450 — I first wrote this template about ten years ago — but these should be easy to adapt to your own aircraft types. What follows is brief description of each section and links to download each Word file.

- acme_corp_com.docx — The introductory stuff.

- acme_corp_operations_manual_0_preliminaries.docx — The preliminaries and, most importantly, the accountable executive letter.

- acme_corp_operations_manual_1_company_organization.docx — An organization chart and job descriptions, which include qualifications, duties, and responsibilities.

- acme_corp_operations_manual_2_safety_management_system.docx — Safety policy and training, the safety management strategy, the hazard tracking system, the Continuous Improvement Opportunity Program, risk assessment, and the Fatigue Risk Management System.

- acme_corp_operations_manual_3_administration_and_scheduling.docx — Personnel policies, scheduling, flight and duty limits, maintenance duty limits.

- acme_corp_operations_manual_4_operational_control_and_flight_planning.docx — flight following, flight planning, weather minima, fuel requirements, aircraft performance, RVSM, special operations airports, weight and balance, airworthiness, and MEL deferral.

- acme_corp_operations_manual_5_standard_operating_procedures.docx — Flight crew qualifications, crew duties, fueling procedures, portable electronic devices, passengers procedures, noise abatement, weather considerations, and other standard operating procedures.

- acme_corp_operations_manual_6_emergency_procedures_and_equipment.docx — PIC authority, crew duties, use of checklists, declaring an emergency, ditching, unplanned landings, emergency response plan, and other emergency procedures.

- acme_corp_operations_manual_7_training.docx — Currency, initial and recurrent training, international operations training, maintenance training, and Aircraft Specific Survey and Emergency Training (ASSET) forms.

- acme_corp_operations_manual_8_aircraft_maintenance.docx — Maintenance control, inspections, scheduled and unscheduled maintenance, records, minimum equipment lists, deferral, airworthiness, weight and balance control, FOD, parts and material control, tooling, flight authorization, and other maintenance procedures.

- acme_corp_operations_manual_9_security_procedures.docx — Threat assessment, hangar security, aircraft security, and response measures.

- acme_corp_operations_manual_10_dangerous_goods.docx — Dangerous goods policy, charts, symbols, and resources.

- acme_corp_operations_manual_11_callouts.docx — Standardized callouts.