We aviators are living in enemy territory, though many of us don’t realize it. If unaware, we are more likely to become victims in this battle. Those who are aware the fight exists, are better prepared. Now I realize the C. S. Lewis quote has more to do with religion – the enemy territory is controlled by Satan, after all – but even if your only religion is aviation, you need to understand your enemy. We operate at altitudes that cannot sustain human life, at temperatures that will freeze human blood, and at speeds no human can naturally achieve. It is a hostile environment that we need to understand if we hope to survive.

— James Albright

1

“Altitudes that cannot sustain human life”

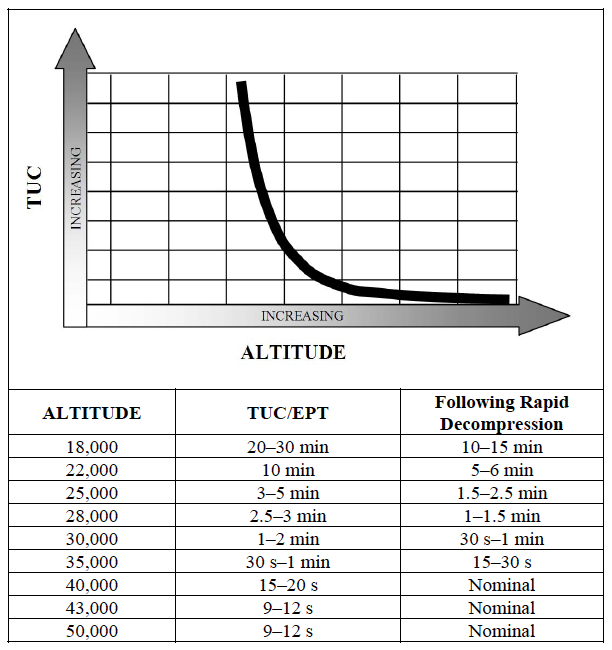

The highest permanent human settlement on earth is La Rinconada, Peru, a gold-mining town in the Andes. It is 16,700 ft. above sea level and many residents suffer from chronic altitude sickness. Most of us will lose consciousness at that altitude after about 30 minutes. Many aviators spend their working hours above 35,000 feet where the Time of Useful Consciousness (TUC) is between 30 and 60 seconds.

All that is fine and good, you may say. Since we fly in pressurized cabins, this isn’t a problem. The average airline cabin altitude is between 6,000 and 8,000 feet. In the business jet world, it is even better. Cruising at 51,000 feet, a Gulfstream G700 has a cabin altitude below 3,000 feet. Ergo: Not a problem.

What if we lose cabin pressure? Hah! We practice for that very situation! We can don oxygen and hurry our way down below 15,000 feet in just a few minutes. Many of us have seen this in altitude chambers and will instantly recognize when this happens: the air in our lungs (and other spaces) rushes from us, the world turns cold and foggy. Yes, there is no mistaking it. But, dear intrepid aviator, is that always the case?

Sometimes the enemy has allies within our ranks, and the sudden loss of cabin pressure becomes so gradual, nobody notices. Not even the pilots. Consider the case of Helios Airways Flight 522 on August 14, 2005. It was a Boeing 737 flying from Larnaca Airport (LCLK), Cyprus to Athens-Eleftherios Venizelos International Airport (LGAT), Greece.

The airplane had a history of pressurization problems and was written up on the day before: “Aft service door (starboard) seal around door freezes and hard bangs are heard during flight.” The company ground engineer performed a visual inspection and then pressurized the aircraft to “max diff” until the safety valve operated and noted “no leaks or abnormal noises.” The engineer failed to use the Aircraft Maintenance Manual, which would have directed the cabin differential brought to 4.0 PSI, the outflow valve closed, and the subsequent pressure loss timed. Showing that maximum pressure differential was possible didn’t prove anything. Adding insult to injury, the ground engineer failed to return the cockpit pressurization panel from MANUAL to AUTOMATIC.

The first officer on the next flight had a history of problems following Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) and didn’t catch the misset switch. They took off with the pressurization system in MANUAL, which left the outflow valve open as the ground engineer had last set it. The crew climbed with the autopilot engaged and programmed to fly the route at 34,000 feet. The first item in the After Takeoff checklist was to check the pressurization system, but the first officer with SOP issues failed to do this.

The aircraft was equipped with a pressurization warning system designed to alert the crew when cabin altitude exceeds 12,000 feet. When this happened, the captain disengaged the autopilot and autothrottles, and retarded the throttles in an attempt to extinguish the warning horn. When this didn’t work, they apparently silenced the sound with a switch meant to do that, and pressed on. Why? The horn used by the pressurization system during flight was identical to the takeoff configuration warning system on the ground. They had probably heard the takeoff configuration warning system many times but never heard that horn in flight.

Passing 17,000 feet the MASTER CAUTION light illuminated for two events: the equipment cooling low flow detectors and the PASS OXY ON light on the overhead panel. This aircraft did not have a Crew Alerting System which listed the issues; it was up to the pilots to scan the entire cockpit. The crew, evidently, only noticed the equipment cooling system problem.

Passengers and crew in the cabin donned their oxygen masks which were not designed for prolonged use at high cabin altitudes. The masks in the cockpit were designed for this, but the crew in the cockpit did not don their oxygen masks. Everyone, except one flight attendant, passed out.

The aircraft automation leveled off at 34,000 feet, flew the route to Athens, the track for the approach and missed approach procedures and entered the published holding pattern. The aircraft continued in the holding pattern until 2 hours 42 minutes after takeoff when the left engine flamed out and the aircraft started to descend in a left turn. Ten minutes later the right engine flamed out and four minutes after that the aircraft impacted the terrain 33 km northwest of the airport. The crew of 6 and all 121 passengers were killed. I write about this incident in more detail here: Case Study: Helios 522.

There is an episode of “Mayday: Air Disaster” that goes into the tragic story of the last survivor, a flight attendant who was a student pilot. The aspiring pilot made it to the cockpit, but in the end, he passed out. All of this was witnessed by a flight of Greek F-16s sent to intercept the airplane. You can see that episode here: https://youtu.be/P52BESqVCd0?si=yCFvGPazfDQZe33T.

Yes, we routinely operate at altitudes that cannot sustain human life and most of us fly entire careers without ever losing cabin pressure. But everything and everyone has to work properly to ensure our safety: those who design the aircraft, those who maintain it, and those who fly it.

2

“Temperatures that will freeze human blood”

Human blood is about 50% water by volume and will freeze between -2°C and -3°C. It doesn’t take much altitude to get colder than that and since we spend most of our cruise time in the tropopause, which is -56°C on a “standard” day, we are existing in a space ill-suited for our survival. Our hollow aluminum tubes are therefore heated, and the problem is solved. Or is it?

As aircraft endurance has increased over the years, we continue to learn that cold temperatures impact more than just the humans in the heated vessel. Fuel is particularly vulnerable. More specifically, the water in the fuel. From our first days flying piston-engine aircraft, we are taught to be wary of water in our fuel tanks. Even jet engines are susceptible and chemical treatment to the fuel or mechanisms in the aircraft are used to reduce the chances of water in the fuel from freezing in fuel lines, pumps, and filters. A typical method to prevent water in fuel from freezing in jet engines is to use Fuel-Oil Heat Exchangers (FOHEs). These are usually located in the engines prior to fuel pumps and other components prone to blockage.

Take, for example, the case of British Airways Flight 38. On January 17, 2008, this Boeing 777 was on final approach into London Heathrow Airport (EGLL), U.K., after flying 10.5 hours from Beijing Capital International Airport (ZBAA), China. Everything appeared to be happening as it always did, everything from takeoff to the initial descent. It wasn’t until final approach, when the thrust was increased to stabilize the aircraft’s descent, that things went awry. At about 720 feet above the ground, both engines rolled back to just above flight idle and would not respond to thrust lever movements. The aircraft touched down about 1,000 feet short of the runway and was damaged beyond repair. Remarkably, there was only one serious injury to the 152 people on board.

At the time of this incident, British Airways had been flying the route with the Boeing 777 for over 12 years. The Boeing 777 has a fuel tank in each wing and a center tank, each with a water scavenge system to prevent large amounts of “free water” in the tanks. Each engine has a FOHE used to raise the temperature of the fuel, so it doesn’t impact downstream components, such as the Low Pressure filter and the Fuel Metering Unit. Investigators determined that “accreted ice from the fuel system released, causing a restriction to the engine fuel flow at the face of the FOHE, on both engines.” The investigation revealed much that was not earlier known.

Research revealed that with normal concentrations of water in jet fuel, ice can form inside fuel lines. The accumulation is dependent on the velocity of the fuel as well as the fuel temperature. Ice accumulation is possible between +5°C and -20°C. Research also revealed that within this “sticky range,” fuel is most “sticky” at around -12°C. On this particular day, the fuel flow was relatively low during cruise after hours of fuel cooling. The fuel flow remained low until the aircraft was on short final, fully configured, and the thrust was increased. “The FOHE, although compliant with the applicable certification requirements, was shown to be susceptible to restriction when presented with soft ice in a high concentration, with a fuel that is below -10°C and a fuel flow above idle. Certification requirements, with which the aircraft and engine fuel systems had to comply, did not take account of this phenomenon as the risk was unrecognized at that time.” I write about this incident in greater detail here: British Airways 38.

Yes, we operate in environments where the temperature is cold enough to freeze our blood. But even more pertinent than that, we operate in environments where our knowledge of what we are doing is imperfect. Given this knowledge shortfall, we would do well to apply caution in everything we do, even if we’ve done it many times before.

3

“Speeds no human can naturally achieve”

The men’s marathon world record is 2 hours, 0 minutes, 35 seconds, set by Kelvin Kiptum of Kenya. That’s a pace of (26.2 miles / 2:00:35) = 13 mph. I’ve run 10 marathons over the years and my fastest is 3 hours, 15 minutes. Much slower: 8 mph. I contend that we humans were biologically designed to think only as fast as it takes to run away from a hungry lion chasing us. Under those conditions, you might perform more like Mr. Kiptum than me. So, for the sake of argument, let’s say you can think at 13 mph.

How fast does your aircraft travel? My Gulfstream GVII cruises all day long at Mach 0.90, which comes to 516 knots at 51,000 feet on a standard day. That converts to 594 mph. But our hungry lion has a lower service ceiling, so let’s consider our aircraft on final approach flying at 120 knots, which comes to 138 mph. That’s ten times faster than you can think. How do you do it? If you are like most professional pilots, you cheat. You don’t have to keep up with the aircraft if you understand how the aircraft flies and what requires your attention. On final approach, for example, you know how to trim the aircraft, so the stick and rudder doesn’t require 100% focus. You understand known power settings and how to adjust those settings for your descent rate and configuration. That’s what you do, even if you don’t know you are doing it. You know what’s important when it is important, and you make decisions that allow you to slow the process down. But there is judgment involved, and not all pilots are created equal in the judgment department.

Before we dive deeper, a quick example from the movies that will help illustrate the point. In “Top Gun Maverick,” the mission requires two F/A-18 Hornets to weave their way through narrow canyons to avoid radar detection. They do this flying very close formation, the second airplane just a few feet from the first. Yes, we pilots are just that good! We can maintain formation with the lead aircraft and still avoid hitting the canyon walls. That only happens in the movies. In real life, the fighters would be in trail formation. Lead sets the speed and the second aircraft sets a power setting to maintain safe distance behind lead to (a) avoid hitting lead, and (b) avoid becoming a part of the terrain. The “best of the best” rely on a technique to reduce the complexity of the task. Now, onto our final case study.

Consider the case of US Airways Flight 1702, an Airbus A320 substantially damaged during takeoff from Philadelphia International Airport (KPHL), PA, on March 13, 2014. It was to be a routine flight on a day with good weather, and a highly experienced crew. The captain, age 61, with over 23,000 total flight time, about 4,500 hours in type, was the pilot flying. The first officer, age 62, had over 13,000 hours total flight time, about 4,700 hours in type and was the pilot monitoring. Despite all that experience, both pilots made several mistakes by making very quick decisions and ignoring their many years of training.

Their A320 was designed to reduce pilot workload by automating many processes, such as computing takeoff performance. While earlier aircraft of this size required the pilots to chase through performance charts to come up with V-speeds, balance field lengths, and engine thrust settings, the Flight Management Computers (FMCs) on most newer aircraft do this for the pilots. Pilots simply enter the conditions, such as the aircraft’s weight, center of gravity, temperature, pressure altitude, etc., and the aircraft does the rest. The first officer normally enters the numbers and both pilots verify the results. And that is where we find ourselves in this case study.

The first officer made all the necessary inputs but made one mistake, she entered Runway 27R instead of their assigned Runway 27L. The crew received instructions to taxi to Runway 27L and they did precisely that. It wasn’t until they were cleared to line up and wait on Runway 27L that the captain noticed the error. He asked her to change the runway on the FMC and she did that, missing one step of the process. Less than a minute later, they were cleared for takeoff.

The captain pushed the throttles to the FLEX detent and the aircraft accelerated. Two seconds later an Electronic Centralized Aircraft Monitoring (ECAM) message indicated the thrust was not set, two seconds later the first officer said, “engine thrust levers not set.” The captain reduced the throttles to the CLIMB detent and back to the FLEX detent and said, “they’re set.”

Sidebar: Airbus pilots will probably see the problem with just this information. But for the rest of us, some explanation is in order. The throttles have several detents above idle: MAX CLIMB, FLEX, MAX CONT, MAX TO/GO AROUND. For takeoff, the system wants to use TO/GA unless the FMC is instructed to use FLEX. The Airbus method for a reduced thrust takeoff, called a FLEX takeoff, is to enter an “assumed temperature,” telling the FMC the temperature is higher than it actually is, which tells it to use less thrust. Without the assumed temperature, the system wants TO/GA thrust. The first officer missed the assumed temperature when she made the last-minute change from Runway 27R to 27L. According to the aircraft manual, the correct response to an “ENG THR LEVERS NOT SET” ECAM message would be to set TO/GA thrust. When investigators asked the captain why he didn’t do this, he said there was “no harm” and left the thrust in FLEX.

As the aircraft accelerated through 86 knots, an aural RETARD alert sounded in the cockpit. The captain immediately accused the first officer, “What did you do? You didn’t load. We lost everything.” Despite this, he continued the takeoff. He later said that since anything above 80 knots was considered high speed, an abort would be too risky.

Sidebar: The RETARD message is something Airbus pilots expect during landing as the aircraft goes below about 20 feet, reminding them to reduce the throttles to idle. An Airbus in-service bulletin released several years before this accident said a RETARD aural alert was possible during takeoff if the computed takeoff thrust setting didn’t match the flight phase. Very few Airbus pilots know this.

At 143 knots, the captain said, “we’ll get that straight when we get airborne.” The first officer said, “Wh? I’m sorry.” She later said she assumed the captain would abort without V-speeds. The captain said he rotated based on the V-speeds of an earlier takeoff, and the nose gear weight on wheels system indicated it was airborne at 164 knots. During all this, the “RETARD” message continued to sound. The captain’s pitch alternated between nose up and nose down, even after the throttles were reduced to idle. The nose came up and then down hard enough to cause the airplane to “bounce” and became airborne, reaching 15 feet above the runway. The aircraft impacted the runway tail first, then the main gear, and then the nose gear hard enough to cause it to collapse. While the aircraft was substantially damaged, nobody was hurt. Passengers evacuated the aircraft with their carry-on bags.

We pilots flatter ourselves when we think we can think as fast as the airplane can get us into trouble. Our SOPs are designed to stack the odds in our favor and while we can often get away with ignoring them, doing so only normalizes our deviations. Common sense tells you that if your FMC doesn’t have the correct runway after you’ve been cleared for takeoff, you aren’t ready for takeoff. We are sometimes fast enough to catch up, but not always. SOP at US Airways was to abort if the V-speeds were absent. In the pre-computerized aircraft days, we could get away with “faking it.” But aircraft software has become so complicated, how can we be sure we’ve considered everything? I write about this incident in greater detail here: Case Study: US Air 1702.

4

How to survive in enemy territory

The odds are stacked against us when we choose to defy gravity. Aircraft have become so complex that no human pilot stands a chance of being able to consider all the intricacies in real time. But there are three simple rules to make it easier to survive in enemy territory. The rules are universal, but let’s look with the US Airways accident for examples.

- Don’t get busy. Question: “What’s the first thing you should do in an emergency and when should you do that?” Answer: “Nothing. And do that immediately.” We all know the easiest way to die in a multi-engine aircraft is to shut down the wrong engine after losing an engine during takeoff. So, we purposely delay that decision until away from the ground and safely climbing. But, as with the US Airways flight, sometimes we paint ourselves into a corner requiring us to get very busy indeed. Here again, the solution is adherence to SOPs. Had the crew simply acknowledged the FMC had the wrong runway, they could have asked to vacate the runway, program the performance numbers correctly, and none of the ensuing problems would have happened.

- Don’t get smart. We openly admit that we can’t know everything and agree that SOPs protect us from gaps in our knowledge. But in the heat of battle, it may seem easier or less embarrassing to come up with an ad hoc solution. But our computerized aircraft are so complicated these days that it is impossible to anticipate all the interwoven connections in software. That the “I’ll just update the runway” resulted in no V-speeds was somewhat predictable. But then the repeating “RETARD” starting at 46 knots? You are smart. But not that smart.

- Do things for a reason. Finally, if everything you do in an airplane hasn’t already been done before, you are in the realm of test pilot duties. None of your passengers signed up for the “privilege” of accompanying you on a test flight. In the words of the Flight 1702’s captain, there was “no harm” in leaving the throttles in FLEX, in violation of the Airbus procedure. He might argue that “no harm” is a reason. If so, it was a very bad reason.

References

(Source material)

Accident to Boeing 777-236, G-YMMM at London Heathrow Airport on 17 January 2008, United Kingdom, Department of Transport, Air Accident Investigation Branch, Report 1/2010.

Hellenic Republic, Air Accident Investigation & Aviation Safety Board Aircraft Accident Report, Helios Airways Flight HCY522, Boeing 737-31S, at Grammatiko, Hellas, on 14 August 2005.

NTSB Aviation Accident Final Report, DCA14MA081, Airbus A320-214, N113UW, 03/13/2014.